10.7: Dmitri Shostakovich - Symphony No. 5

- Page ID

- 90745

One of the most famous pieces of protest music in the European concert tradition might not have been a protest at all. Experts still debate the meaning of Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 5. Some believe that it was a harsh rejection of the totalitarian regime under which he lived and worked, while others are skeptical of this interpretation. Because Symphony No. 5 is a piece of absolute music (instrumental music that does not narrate an explicit story), it can be interpreted in many different ways. While this leaves the message in question, it has also permitted the work to have a powerful impact on generations of listeners.

Music in the Soviet Union

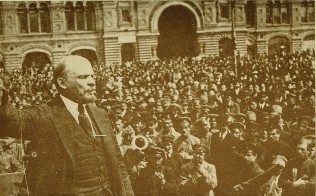

Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975) was born shortly before the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution, in which the longstanding Czarist regime was overthrown and the Soviet Union was born. The revolution brought hope to many Russians. Life under the Czars had been difficult for all but the aristocracy, with no chance for upward mobility and little freedom. The new government promised to improve the lot of Russia’s working class, bringing opportunities for education and economic success.

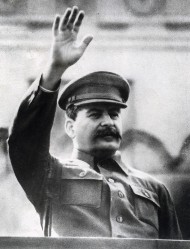

Soon, however, the Soviet Union ran into trouble. After the first decade, economic hardships led to dissatisfaction. At the same time, Joseph Stalin, who had become head of the government followed the death of Vladimir Ilyich Lenin in 1924, set out to consolidate his power. While the Soviet Union was meant to be governed by a committee, Stalin soon had absolute control. Part of his strategy was to deflect blame for the nation’s struggles onto others. In the 1930s, he held a series of public “show trials” in which prominent members of the government were convicted of crimes against the Soviet people. In this way he purged the government of all those who did not support him while positioning himself as an advocate of the people.

This is the environment in which Shostakovich finished his education and began his career. Shostakovich gained international fame at the age of 19, when his Symphony No. 1 was well received not only in the Soviet Union but in Europe as well. At first, unsurprisingly, the young composer produced music in support of the government. Many of his early works explicitly praised Soviet leaders and celebrated the revolution. It seems that he personally felt optimistic about his nation’s future.

The arts, however, faced difficult times under Stalin. Stalin believed in the power of artists to influence public opinion and encourage dissent. For this reason, he went to great lengths to keep creative workers under control. He did so through a combination of censorship, intimidation, and outright murder.

Stalin’s strategy for taking control of the music establishment was very clever indeed. He began in 1929 by reforming the nation’s music conservatories (prestigious schools that trained performers, conductors, scholars, and composers). His first move was to fire the faculty and replace them with partisans. Next he changed the admission standards, such that only students from working-class backgrounds were permitted to attend. These reforms were to be short lived, but he had made his point. When the professors were allowed to return to their posts, they understood that Stalin had total power over their careers (and lives) and were ready to fall into line.

In 1932, Stalin formed the Union of Soviet Composers (USC), a national organization in which all composers were required to participate. The purpose of the USC was to ensure that members only created music that upheld the values of the government and portrayed it in a positive light. Members were required to hold each other accountable and report any deviant behavior to the authorities. With all of the composers living in fear and spying on one another, Stalin was in a position to dictate the messages that were being broadcast in concert halls and opera houses.

All composers were required to uphold the doctrine of Socialist Realism. Exactly what constituted Socialist Realism was never made entirely clear, which is what gave the doctrine its power. Stalin always had the final say concerning any individual work, and his judgment alone could determine whether the composer had met the required standard or not. All artistic works, however, were expected to portray the communist revolution in a positive light. They were to be optimistic and uplifting. And they were certainly not permitted to criticize the Soviet Union or depress the consumer. Stalin also required that concert music be accessible to all citizens, and he preferred that it be based on popular or folk styles. If a musical work was condemned as formalist, then it had failed to achieve these goals, and the composer would face serious repercussions.

Shostakovich’s Condemnation

Following the success of his Symphony No. 1, Shostakovich continued to climb the ranks of Soviet composers. By the 1930s, he was certainly the best known and most influential. When he finally ran afoul of the government, therefore, it was a major event.

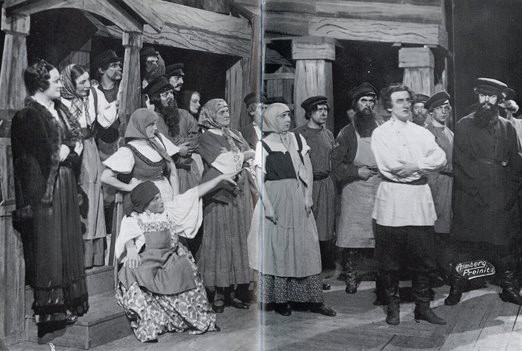

In 1934, Shostakovich premiered an opera (his second) entitled Lady Macbeth of the Mtsenk District. The opera was based on an 1865 novella by Nicolai Leskov that centered on Katerina, the neglected wife of a well-to-do merchant. In the novella, Katerina has an affair that ultimately leads to her and her lover committing a series of murders to protect their secret. After they are captured, convicted, and sent to a prison work camp, the man leaves Katerina for another female prisoner. Overcome with fury and grief, Katerina seizes him and leaps into an icy river, where they both perish.

In short, Lady Macbeth of the Mtsenk District featured a typical operatic narrative, full of romance and violence and ending in tragedy. The opera was a huge success in Leningrad and Moscow, performing to enthusiastic audiences for two years. Then, in 1936, Stalin himself attended a performance in Moscow. He had recently attended a performance of Ivan Dzerzhinsky’s opera Quiet Flows the Don—an overtly pro-government work with little artistic merit. (Ironically, much of the opera had been orchestrated by Shostakovich, who stepped in to help his less-adept colleague.) Stalin publicly demonstrated his support, giving the piece a standing ovation and insisting upon meeting the composer. Nine days later, he saw Lady Macbeth. This time, Stalin did not even stay to the end.

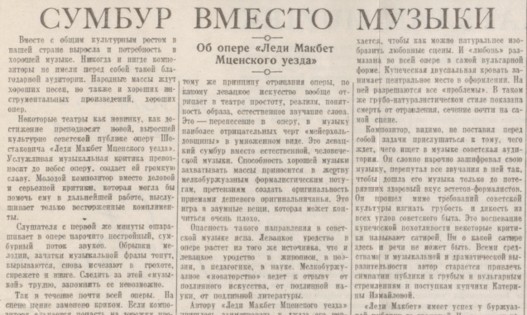

The next day, an article entitled “Muddle Instead of Music” appeared in Pravda, the official government newspaper. The article was unsigned, but readers understood that it spoke for Stalin himself. The article began by condemning Lady Macbeth in terms of subject matter and musical expression. The opera celebrated corruption, reveled in degradation, and lacked musical clarity. Next the author began to attack past works of Shostakovich, arguing that he had been working against the doctrine of Socialist Realism for many years. Finally, the article included a clear warning for the composer: If Shostakovich did not mend the error in his ways, he might find himself in serious trouble.

This anonymous article raises some questions. Why did Lady Macbeth come under condemnation two years after it had premiered and after it had been well received? How was it that many of Shostakovich’s pieces that had previously been accepted as “good” were suddenly denounced as “bad”? What was the purpose of this article? Although we can never know for sure, it seems likely that Shostakovich had simply become too successful—and therefore too powerful. With a single anonymous article, Stalin was able to put him in his place.

The article meant an immediate halt to all aspects of Shostakovich’s career. Performances of his work were cancelled and commissions were withdrawn. The composer himself called off the premiere of his Symphony No. 4, which had been about to take place. He lost all standing in the Union of Soviet Composers and was essentially blacklisted.

Shostakovich also feared for his life. In fact, for a month following the publication of the article he spent nights on his porch so that the police would not wake up his children when they came to arrest him. His fears were justified, for many other composers had already disappeared, having been taken away to prisons or work camps. However, the police did not come, and after a time Shostakovich’s thoughts turned to the revitalization of his career. In order to be readmitted to the music establishment, he needed to be formally rehabilitated. This process required a public apology and the creation of a new work that would demonstrate his contrition. With rehabilitation in mind, he began work on his Symphony No. 5.

Symphony No. 5

When Symphony No. 5 premiered in Leningrad in 1937, it was accompanied by another article, this time signed by the composer. The article was entitled “An artist’s creative response to just criticism.” In it, Shostakovich (or, more likely, a government agent writing on his behalf) admitted that he had strayed from the path illuminated by Socialist Realism but proclaimed that he had seen the error in his ways and desired to reform. He described Symphony No. 5 as an autobiographical account of his personal suffering and rebirth, culminating in a return to optimism. The symphony does indeed follow a general trajectory from darkness to light—the same trajectory as Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5, which clearly served as a model (see Chapter 7). The first movement is angsty and tormented. Its jagged melodies and sparse instrumentation seem to portray devastation and hopelessness. The brief second movement is a bizarre waltz. The third and fourth movements, however, bring the listener through catharsis to a possible triumph, and it is these that we will examine closely.

Movement III

According to reports, the audience wept throughout the third movement of Symphony No. 5.20 The music is certainly sorrowful. A dirge-like tempo combines with winding melodies in the minor mode to express an unmistakable despair. Sometimes the instruments imitate speech, as if they are attempting to put into words an emotion that cannot be spoken. Shostakovich’s orchestration is sparse: He includes only strings, harp, and a few solo winds, each of which take their turn with the melody.

|

Symphony No. 5, Movement III. 20. Composer: Dmitri Shostakovich. Performance: San Francisco Symphony, conducted by Michael Tilson Thomas (2009) |

This funeral chant by Pavel Chesnokov is typical of Russian Orthodox music.

However, there is another explanation for the listeners’ reaction. In this movement, Shostakovich captures the sound of Russian Orthodox funeral music.21 This would have resonated with his audience on several levels. To begin with, times were very difficult in the late 1930s, as the Soviet population was devastated by famine and disease. Everyone in the hall knew someone who had died, and everyone was mourning. At the same time, the government had abolished the Russian Orthodox religion and closed the churches. Nobody had heard this music for decades. As such, it also represented the past and all that had been lost. Despite its portrayals of agony, however, the third movement concludes on a note of hope. The final minutes are calm, and the closing chords are in the major mode.

Movement IV

The fourth movement begins with a terrifying crash, as pounding drums introduce a militaristic minor-mode theme in the brass. The music grows in excitement for several minutes before giving way to a period of calm. In this middle section, Shostakovich introduces a quote from a song he had composed years before using a text by the poet Alexander Pushkin. The title of the song is, in fact, “Rebirth,” and it describes the process of peeling away an outer layer accumulated over time to reveal the true substance beneath. After this interlude, the music regains momentum, building to a dramatic major-mode conclusion. It is here, however, that we must pause to debate what this music really means.

| Bernstein | Petrenko | What to listen for |

|---|---|---|

|

0’00 |

0’00” |

The finale starts with a trill in the winds that leads to pounding timpani and an aggressive brass theme; the energy continues to grow as the tempo increases |

|

3’03” |

3’23” |

The tempo slows and the energy dissipates |

|

4’46” |

5’24” |

The violins quote from Shostakovich’s song “Rebirth” |

|

6’40” |

7’42” |

The build to the Coda begins; Bernstein takes a quick tempo from the start, while Petrenko takes a relaxed tempo |

|

8’10” |

10’54” |

The Coda begins; Bernstein’s tempo is more than twice that of Petrenko |

The closing passage of Symphony No. 5 features the ringing, high notes of trumpets, backed up by the entire orchestra. Played at a fast tempo, as it often is, the music is thrilling and triumphant. However, this approach to performing the coda seems to have derived from a misprint in the first published version of the symphony, which indicated a lively tempo of 188 quarter notes per minute. In reality, Shostakovich wanted this passage to be performed at a tempo of 184 eighth notes per minute, which, at less than half of the misprinted tempo, is quite slow. At this speed, the music sounds not triumphant but painful. The trumpet players agonize as they blast out their high notes, while the string players saw back and forth for minutes on end. One can literally hear the suffering of the musicians. When the symphony finally ends, it is with a sensation of exhaustion, not overcoming, as if the orchestra has been beaten into submission. Some commentators have described the passage as a false smile, put on because the authorities have required as much—but not a true representation of joy.

What does it mean?

The controversy over the tempo is only part of the story. For many decades, fans of Shostakovich have wanted to hear Symphony No. 5 as protest music and to believe that the composer was defying the government. They received confirmation in 1979, when Soviet musicologist Solomon Volkov published a book entitled Testimony. Volkov claimed that he had sat with Shostakovich during his final weeks and written down the composer’s reminiscences. In Testimony, Volkov confirmed that Shostakovich had always stood in opposition to the Soviet regime and that Symphony No. 5 was indeed meant to protest its oppressive rule. However, Volkov was almost immediately discredited by Shostakovich’s wife, who said that he and her husband were hardly even acquainted. Few continue to take his account seriously.

The response following the concert was also mixed. Some critics did not feel that Shostakovich had successfully communicated the personal metamorphosis outlined in his article. The third movement, they felt, was simply too sad, while the fourth movement failed to offer the transformative rebirth that was promised. However, the audience was thrilled, and gave the symphony a thirty-minute standing ovation. Perhaps for this reason, the government officially accepted Shostakovich’s apology and declared him rehabilitated. He was able to return to his work—although with the knowledge that Stalin could end his career (and his life) if he failed to keep in line.

The controversy surrounding Symphony No. 5 is possible because of its status as absolute music. On the one hand, it is just a symphony—just music, just sound. It is titled with a number, and the movements are marked only with their tempos. It is therefore impossible to prove that the music is about one thing or another. The symphony’s various contexts, however, which include its role as Shostakovich’s rehabilitation piece, the accompanying article, the musical references, and its expressive language, give us a great deal of material to use in debate. The symphony must be about something. To this day, however, noone has conclusively proven what Shostakovich meant to communicate with his Symphony No. 5.