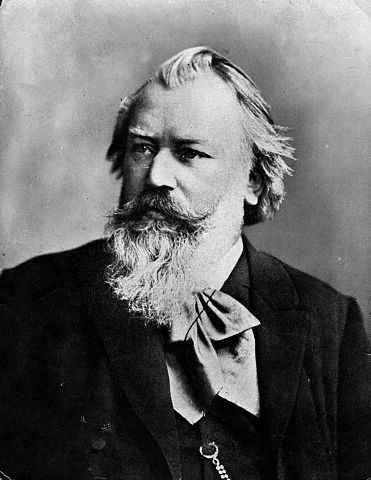

6.9: Music of Johannes Brahms (1833-1897)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

Whereas Berlioz’s program symphony might be heard as a radical departure from earlier symphonies, the music of Johannes Brahms is often thought of as breathing new life into classical forms. For centuries, musical performances were of compositions by composers who were still alive and working. In the nineteenth century that trend changed. By the time that Johannes Brahms was twenty, over half of all music performed in concerts was by composers who were no longer living; by the time that he was forty, that amount increased to over two-thirds. Brahms knew and loved the music of forebears such as Bach, Handel, Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert, and Schumann. He wrote in the genres they had developed, including symphonies, concertos, string quartets, sonatas, and songs. To these traditional genres and forms, he brought sweeping nineteenth-century melodies, much more chromatic harmonies, and the forces of the modern symphony orchestra. He did not, however, compose symphonic poems or program music as did Hector Berlioz and Franz Liszt.

Brahms himself was keenly aware of walking in Beethoven’s shadow. In the early 1870s, he wrote to conductor friend Hermann Levi, “I shall never compose a symphony.” Continuing, he reflected, “You have no idea how someone like me feels when he hears such a giant marching behind him all of the time.” Nevertheless, some six years later, after a twenty-year period of germination, he premiered his first symphony. Brahms’s music engages Romantic lyricism, rich chromaticism, thick orchestration, and rhythmic dislocation in a way that clearly goes beyond what Beethoven had done. Still, his intensely motivic and organic style, and his use of a four movement symphonic model that features sonata, variations, and ABA forms is indebted to Beethoven.

The third movement of Brahms’s First Symphony is a case in point. It follows the ABA form, as had most moderate-tempo, dance-like third movements since the minuets of the eighteenth-century symphonies and scherzos of the early nineteenth-century symphonies. This movement uses more instruments and grants more solos to the woodwind instruments than earlier symphonies did (listen especially for the clarinet solos). The musical texture is thicker as well, even though the melody always soars above the other instruments. Finally, this movement is more graceful and songlike than any minuet or scherzo that preceded it. In this regard, it is more like the lyrical character pieces of Chopin, Mendelssohn, and the Schumanns than like most movements of Beethoven’s symphonies. But, it does not have an extra musical referent; in fact, Brahms’ music is often called “absolute” music, that is, music for the sake of music. The music might call to a listener’s mind any number of pictures or ideas, but they are of the listener’s imagination, from the listener’s interpretation of the melodies, harmonies, rhythms, and textures written by Brahms. In this way, such a movement is very different than a movement from a program symphony such as Berlioz’s Symphonie fantastique. Public opinion has often split over program music and absolute music. What do you think? Do you prefer a composition in which the musical and extra musical are explicitly linked, or would you rather make up your own interpretation of the music, without guidance from a title or story?

|

Listening Guide For audio, go to: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dekswN0JqCs Performed by the Berlin Philharmonic Herbert von Karajan conducting |

| Composer: Johannes Brahms |

| Composition: Symphony No. 1 in C minor, Op. 68, III. Un poco allegretto e grazioso [a little allegretto and graceful] |

| Date: 1876 |

| Genre: Symphony |

| Form: ABA moderate-tempoed, dancelike movement from a symphony |

|

Performing Forces: Romantic symphony orchestra, including two flutes, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, one contrabassoon, four horns, two trum- pets, three trombones, timpani, violins (first and second), violas, cellos, and double basses |

|

What we want you to remember about this composition:

|

|

Other things to listen for: •The winds as well as the strings get the melodic themes from the beginning |

| Timing | Performing Forces, Melody, and Texture | Text and Form |

|

0:00 |

Clarinet solo with descending ques- tion phrases answer phrase in the flutes. |

A |

|

1:01 |

Second theme: starts with a clarinet solo and then with the whole wood- wind section. |

|

| 1:26 | Return of opening theme (clarinet solo) |

|

1:41 |

New theme introduced and repeated by different groups in the orchestra. |

B |

|

3:17 |

First theme returns answer theme in the strings (varied form). Sparser accompaniment again Softer dynamic |

’A’ |

| 3:32 | Second theme: This time it is extended using sequences | |

| 4:00 | Ascending sequential treatment of Coda motives from the movement | Coda |

As noted at the beginning of this chapter, political and cultural nationalism strongly influenced many creative works of the nineteenth century. We have already observed aspects of nationalism in the piano music of Chopin and Liszt. Later nineteenth-century composers invested even more heavily in nationalist themes.