2.1: Introduction and Historical Context

- Page ID

- 54819

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)| Event in History | Events in music |

|

From the 1st Century CE: Spread of Christianity through the Roman Empire 4th Century CE: Founding of the monastic movement in Christianity c. 450 CE: Fall of Rome 11th Century CE: Rise of Feudalism & the Three Estates 11th Century CE: Growth of Marian Culture 1088 CE: Founding of the University of Bologna c. 1095-1291 CE: The Crusades c. 1163-1240s CE: Building of Notre Dame in Paris and the rise of Gothic architecture 13th Century CE: Development of Polyphony 1346-53: Height of the Bubonic Plague (Black Death) |

2nd millennia BCE: First Hebrew Psalms are written 7th Century BCE: Ancient Greeks and Romans use music for entertainment and religious rites 6th Century BCE: Pythagoras and his experiments with acoustics 4th Century BCE: Plato and Aristotle write about music c. 400 CE: St Augustine writes about church music 4th – 9th Century CE: Development/Codification of Christian Chant c. 800 CE: First experiments in Western Music 11st Century CE: Guido of Arezzo refines of mu11 sic notation and development of solfège 12th Century CE: Hildegard of Bingen writes Gregorian chnat 13th Century CE: Development of Polyphony c. 1275 CE: King Alfonso the Wise collects early songs in an exquisitely illuminated manuscript 14th Century CE: Further refinement of musical notation, including notation for rhythm 1300-1377 CE: Guillaume de Machaut composes songs and church music |

Introduction

What do you think of when you hear the term the Middle Ages (450-1450)? For some, the semi-historical figures of Robin Hood and Maid Marian come to mind. Others recall Western Christianity’s Crusades to the Holy Land. Still others may have read about the arrival in European lands of the bubonic plague or Black Death, as it was called. For most twenty-first-century individuals, the Middle Ages seem far removed. Although life and music were quite different back then, we hope that you will find that there are cultural threads that extend from that distant time to now.

We normally start studies of Western music with the Middle Ages, but of course, music existed long before then. In fact, the term Middle Ages or medieval period got its name to describe the time in between (or “in the middle of”) the ancient age of classical Greece and Rome and the Renaissance of Western Europe, which roughly began in the fifteenth century. Knowledge of music before the Middle Ages is limited but what we do know largely revolves around the Greek mathematician Pythagoras, who died around 500 B.C.E. (See his profile on a third century ancient coin: Figure 2.1.1)

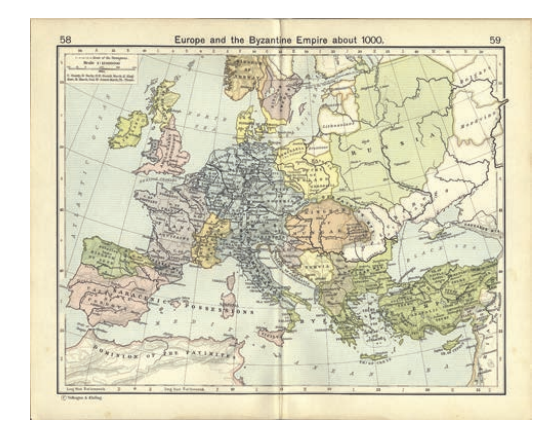

Pythagoras might be thought of as a father of the modern study of acoustics due to his experimentation with bars of iron and strings of different lengths. Images of people singing and playing instruments, such as those found on the Greek vases provide evidence that music was used for ancient theater, dance, and worship. The Greek word musicka referred to not music but also referred to poetry and the telling of history. Writings of Plato and Aristotle referred to music as a form of ethos (an appeal to ethics). As the Roman Empire expanded across Western Europe, so too did Christianity (see Figure 2.1.2, a map of Western Europe around 1000). Considering that Biblical texts from ancient Hebrews to those of early Christians, provided numerous records of music used as a form of worship, the Empire used music to help unify its people: the theory was that if people worshipped together in a similar way, then they might also stick together during political struggles.

Later, starting around 800 CE, Western music is recorded in a notation that we can still decipher today. This brief overview of these five hundred years of the Roman Empire will help us better understand the music of the Middle Ages.

Historical Context for Music of the Middle Ages (800-1400)

During the Middle Ages, as during other periods of Western history, sacred and secular worlds were both separate and integrated. However during this time, the Catholic Church was the most widespread and influential institution and leader in all things sacred. The Catholic Church’s head, the Pope, maintained political and spiritual power and influence among the noble classes and their geographic territories; the life of a high church official was not completely different from that of a noble counterpart, and many younger sons and daughters of the aristocracy found vocations in the church. Towns large and small had churches, spaces open to all: commoners, clergy, and nobles. The Catholic Church also developed a system of monasteries, where monks studied and prayed, often in solitude, even while making cultural and scientific discoveries that would eventually shape human life more broadly. In civic and secular life, kings, dukes, and lords wielded power over their lands and the commoners living therein. Kings and dukes had courts, gatherings of fellow nobles, where they forged political alliances, threw lavish parties, and celebrated both love and war in song and dance.

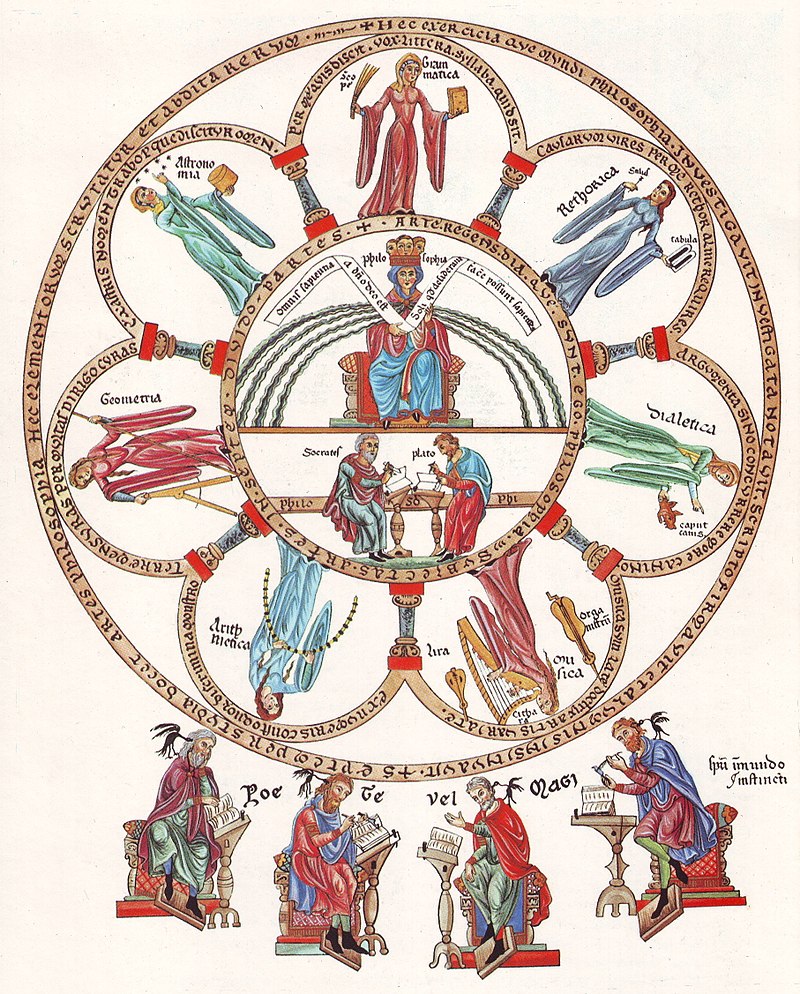

Many of the important historical developments of the Middle Ages arose from either in the church or the court. One such important development stemming from the Catholic Church would be the developments of architecture. During this period, architects built increasingly tall and imposing cathedrals for worship through the technological innovations of pointed arches, flying buttresses, and large cut glass windows. This new architectural style was referred to as “gothic,” which vastly contrast the Romanesque style, with its rounded arches and smaller windows. Another important development stemming from the courts occurred in the arts. Poets and musicians, attached to the courts, wrote poetry, literature, and music, less and less in Latin—still the common language of the church—and increasingly in their own vernacular languages (the predecessors of today’s French, Italian, Spanish, German, and English). However, one major development of the Middle Ages spanned sacred and secular worlds: universities shot up in locales from Bologna, Italy, and Paris, France, to Oxford, England (the University of Bologna begin the first). At university, a young man could pursue a degree in theology, law, or medicine. Music of a sort was studied as one of the seven liberal arts and sciences, specifically as the science of proportions. (Look for music in this twelfth-century image of the seven liberal arts from the Hortus deliciarum of the Herrad of Landsberg (Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\)).