1.9: Putting it All Together

- Page ID

- 54768

1.11.1 Form in Music

When we talk about musical form, we are talking about the organization of musical elements—melody, harmony, rhythm, texture, timbre—in time. Because music is a temporal art, memory plays an important role in how we experience musical form. Memory allows us to hear repetition, contrast, and variation in music. And it is these elements that provide structure, coherence, and shape to musical compositions.

A composer or songwriter brings myriad experiences of music, accumulated over a lifetime, to the act of writing music. He or she has learned how to write music by listening to, playing, and studying music. He or she has picked up, consciously and/or unconsciously, a number of ways of structuring music. The composer may intentionally write music modeled after another group’s music: this happens all of the time in the world of popular music where the aim is to produce music that will be disseminated to as many people as possible. In other situations, a composer might use musical forms of an admired predecessor as an act of homage or simply because that is “how it’s always been done.” We find this happening a great deal in the world of folk music, where a living tradition is of great importance. The music of the “classical” period (1775-1825) is rich with musical forms as heard in the works of masters such as Joseph Haydn and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. In fact, form plays a vital role in most Western art music (discussed later in the chapter) all the way into the twenty-first century. We will discuss these forms, such as the rondo and sonata-allegro, in later chapters, but for the purpose of this introduction, we will focus on those that might be more familiar to the modern listener.

1.11.2 The Twelve-Bar Blues

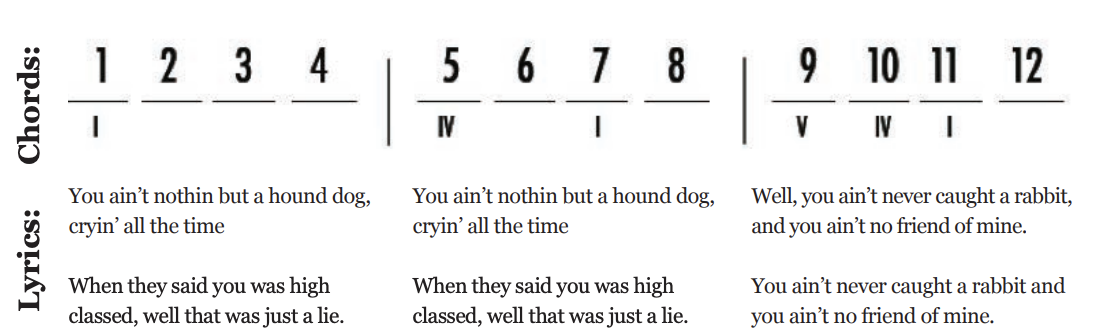

Many compositions that on the surface sound very different use similar musical forms. A large number of jazz compositions, for example, follow either the twelve-bar blues or an AABA form. The twelve-bar blues features a chord progression of I-IV-I-V-IV-I. Generally the lyrics follow an AAB pattern, that is, a line of text (A) is stated once, repeated (A), and then followed by a response statement (B). The melodic idea used for the statement (B) is generally slightly different from that used for the opening a phrases (A). This entire verse is sung over the I-IV-I-V-IV-I progression. The next verse is sung over the same pattern, generally to the same melodic lines, although the singer may vary the notes in various places occasionally.

Listen to Elvis Presley’s version of “Hound Dog” (1956) using the link below, and follow the chart below to hear the blues progression.

Ex. 1.18: Elvis Presley “Hound Dog” (1956)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5ZdC6oQKU-w

This blues format is one example of what we might call musical form. It should be mentioned that the term “blues” is used somewhat loosely and is sometimes used to describe a tune with a “bluesy” sound, even though it may not follow the twelve-bar blues form. The blues is vitally important to American music because it influenced not only later jazz but also rhythm and blues and rock and roll.

1.11.3 AABA Form

Another important form to jazz and popular music is AABA form. Sometimes this is also called thirty-two-bar form; in this case, the form has thirty-two measures or bars, much like a twelve-bar blues has twelve measures or bars. This form was used widely in songs written for Tin Pan Alley, Vaudeville, and musicals from the 1910s through the 1950s. Many so-called jazz standards spring from that repertoire. Interestingly, these popular songs generally had an opening verse and then a chorus. The chorus was a section of thirty-two-bar form, and often the part that audiences remembered. Thus, the chorus was what jazz artists took as the basis of their improvisations.

“(Somewhere) Over the Rainbow,” as sung by Judy Garland in 1939 (accompanied by Victor Young and his Orchestra), is a well-known tune that is in thirty-two-bar form.

Ex. 1.19: Judy Garland “(Somewhere) Over the Rainbow” (1939)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PSZxmZmBfnU

After an introduction of four bars, Garland enters with the opening line of the text, sung to melody A. “Somewhere over the rainbow way up high, there’s a land that I heard of once in a lullaby.” This opening line and melody lasts for eight bars. The next line of the text is sung to the same melody (still eight bars long) as the first line of text. “Somewhere over the rainbow skies are blue, and the dreams that you dare to dream really do come true.” The third part of the text is contrasting in character. Where the first two lines began with the word “somewhere,” the third line begins with “someday.” Where the first two lines spoke of a faraway place, the third line focuses on what will happen to the singer. “Someday I’ll wish upon a star, and wake up where the clouds are far, behind me. Where troubles melt like lemon drops, away above the chimney tops, that’s where you’ll find me.” It is sung to a contrasting melody B and is eight bars long. This B section is also sometimes called the “bridge” of a song. The opening a melody returns for a final time, with words that begin by addressing that faraway place dreamed about in the first two A sections and that end in a more personal way, similar to the sentiments in the B section. “Somewhere over the rainbow, bluebirds fly. Birds fly over the rainbow. Why then, oh why can’t I?” This section is also eight bars long, adding up to a total of thirty-two bars for the AABA form.

Although we’ve heard the entire thirty-two-bar form, the song is not over. The arranger added a conclusion to the form that consists of one statement of the A section, played by the orchestra (note the prominent clarinet solo); another restatement of the A section, this time with the words from the final statement of the A section the first time; and four bars from the B section or bridge: “If happy little bluebirds…Oh why can’t I.” This is a good example of one way in which musicians have taken a standard form and varied it slightly to provide interest. Now listen to the entire recording one more time, seeing if you can keep up with the form.

1.11.4 Verse and Chorus Forms

Most popular music features a mix of verses and choruses. A chorus is normally a set of lyrics that recur to the same music within a given song. A chorus is sometimes called a refrain. A verse is a set of lyrics that are generally, although not always, just heard once over the course of a song.

In a simple verse-chorus form, the same music is used for the chorus and for each verse. “Can the Circle Be Unbroken” (1935) by The Carter Family is a good example of a simple verse-chorus form. Many childhood songs and holiday songs also use a simple verse-chorus song.

Ex. 1.20: The Carter Family “Can the Circle Be Unbroken” (1935)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qjHjm5sRqSA

In a simple verse form, there are no choruses. Instead, there is a series of verses, each sung to the same music. Hank Williams’s “I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry” (1949) is one example of a simple verse form. After Williams sings two verses, each sixteen bars long, there is an instrumental verse, played by guitar. Williams sings a third verse followed by another instrumental verse, this time also played by guitar. Williams then ends the song with a final verse.

Ex. 1.21: Hank Williams: I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry (1949)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oyTOZCfp8OY

A contrasting verse-chorus form features different music for its chorus than for the statement of its verse(s). “Light my Fire” by the Doors is a good example of a contrasting verse-chorus form. In this case, each of the two verses are repeated one time, meaning that the overall form looks something like: intro, verse 1, chorus, verse 2, chorus, verse 2, chorus, verse 1, chorus. You can listen to “Light my Fire” by clicking on the link below.

Ex. 1.22: The Doors, “Light my Fire” (1967)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=deB_u-to-IE

Naturally, there are many other forms that music might take. As you listen to the music you like, pay attention to its form. You might be surprised by what you hear!

1.11.5 Composition and Improvisation

Music from every culture is made up of some combination of the musical elements. Those elements may be combined using one of two major processes; composition and improvisation.

Composition

Composition is the process whereby a musician notates musical ideas using a system of symbols or using some other form of recording. We call musicians who use this process “composers.” When composers preserve their musical ideas using notation or some form of recording, they intend for their music to be reproduced the same way every time.

Listen to the recording of Mozart’s music linked below. Every element of the music was carefully notated by Mozart so that each time the piece is performed, it can be performed exactly the same way.

Ex. 1.23: Mozart “Piano Sonata K.457 in C minor” (1989)

www.youtube.com/watch?v=JrUH5VAetEg

Improvisation

Improvisation is a different process. It is the process whereby musicians create music spontaneously using the elements of music. Improvisation still requires the musician to follow a set of rules. Often the set of rules has to do with the scale to be used, the rhythm to be used, or other musical requirements using the musical elements.

Listen to the example of Louis Armstrong below. Armstrong is performing a style of early New Orleans jazz in which the entire group improvises to varying degrees over a set musical form and melody. The piece starts out with a statement of the original melody by the trumpet, with Armstrong varying the rhythm of the original written melody as well as adding melodic embellishments. At the same time, the trombone improvises supporting notes that outline the harmony of the song and the clarinet improvises a completely new melody designed to complement the main melody of the trumpet. The rhythm section of piano, bass, and drums are improvising their accompaniment underneath the horn players, but are doing so within the strict chord progression of the song. The overall effect is one in which you hear the individual expressions of each player, but can still clearly recognize the song over which they are improvising. This is followed by Armstrong interpreting the melody. Next we hear individual solos improvised on the clarinet, the trombone, and the trumpet. The piece ends when Armstrong sings the melody one last time.

Ex. 1.24: Louis Armstrong, “When the Saints Go Marching In” (1961)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5WADCJ4_KmU

Composition and Improvisation Combined

In much of the popular music we hear today, like jazz and rock, both improvisation and composition are combined. Listen to the example linked below of Miles Davis playing “All Blues.” The trumpet and two saxophones play an arrangement of a composed melody, then each player improvises using the scale from which the melody is derived. This combined structure is one of the central features of the jazz style and is also often used in many popular music compositions.

Ex. 1.25: Miles Davis “All Blues” (1949)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uRBgy43gCoQ

1.11.6 Music and Categories

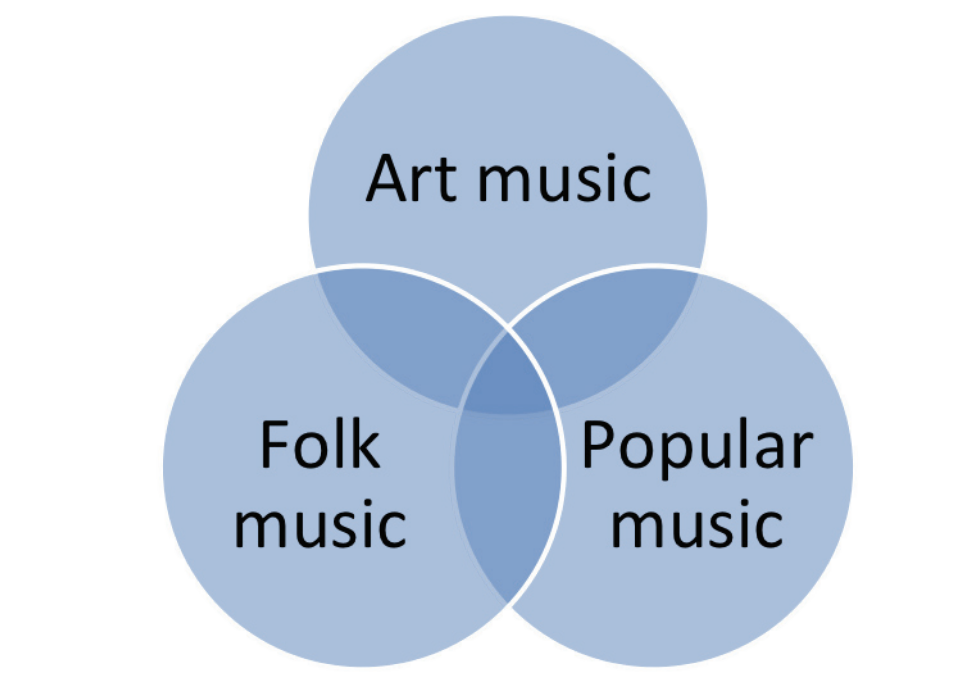

Categorizing anything can be difficult, as items often do not completely fit in the boxes we might design for them. Still, categorizing is a human exercise by which we attempt to see the big picture and compare and contrast the phenomenon we encounter, so that we can make larger generalizations. By categorizing music we can attempt to better understand ways in which music has functioned in the past and continues to function today. Three categories which are often used in talking about music are (1) art music, (2) folk music, and (3) popular music. These categories can be seen in the Venn diagram below:

Much of the music that we consider in this book falls into the sphere of art music in some way or form. It is also sometimes referred to as classical music and has a written musical tradition. Composers of art music typically hope that their creative products will be played for many years. Art music is music that is normally learned through specialized training over a period of many years. It is often described as music that stands the test of time. For example, today, if you go to a symphony orchestra concert you will likely hear music composed over a hundred years ago. Folk music is another form of music that has withstood the test of time, but in a different way.

Folk music derives from a particular culture and is music that one might be expected to learn from a family at a young age. Although one can study folk music, the idea is that it is accessible to all; it generally is not written down in musical notation until it becomes an object of scholarship. Lullabies, dance music, work songs, and some worship music are often considered folk music as they are integrated with daily life.

Popular music is marked by its dissemination to large groups of people. As such, it is like folk music. But popular music is generally not expected to be passed down from one generation to the next as happens with folk music. Instead, as its name implies, it tends to appeal to the masses at one moment in time. To use twentieth-century terminology, it often hits the charts in one month and then is supplanted by something new in the next month. Although one might find examples of popular music across history, popular music has been especially significant since the rise of mass media and recording technologies in the twentieth century. Today, music can be put online and instantly go viral around the world. Some significant twentieth-century popular music is discussed in chapter eight.