1.1: What is Music?

- Page ID

- 54316

Music moves through time; it is not static. In order to appreciate music we must remember what sounds happened, and anticipate what sounds might come next. Most of us would agree that not all sounds are music! Examples of sounds not typically thought of as music include noises such as alarm sirens, dogs barking, coughing, the rumble of heating and cooling systems, and the like. But, why? One might say that these noises lack many of the qualities that we typically associate with music.

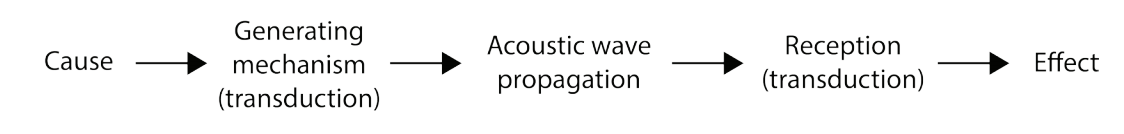

We can define music as the intentional organization of sounds in time by and for human beings. Though not the only way to define music, this definition uses several concepts important to understandings of music around the world. “Sounds in time” is the most essential aspect of the definition. Music is distinguished from many of the other arts by its temporal quality; its sounds unfold over and through time, rather than being glimpsed in a moment, so to speak. They are also perceptions of the ear rather than the eye and thus difficult to ignore; as one can do by closing his or her eyes to avoid seeing something. It is more difficult for us to close our ears. Sound moves through time in waves. A sound wave is generated when an object vibrates within some medium like air or water. When the wave is received by our ears it triggers an effect known as sound, as can be seen in the following diagram:

As humans, we also tend to be interested in music that has a plan, in other words, music that has intentional organization. Most of us would not associate coughing or sneezing or unintentionally resting our hand on a keyboard as the creation of music. Although we may never know exactly what any songwriter or composer meant by a song, most people think that the sounds of music must show at least a degree of intentional foresight. A final aspect of the definition is its focus on humanity. Bird calls may sound like music to us; generally, the barking of dogs and the hum of a heating unit do not. In each of these cases, though, the sounds are produced by animals or inanimate objects, rather than by human beings; therefore the focus of this text will only be on sounds produced by humans.

Acoustics

Acoustics is “the science of sound.” It investigates how sound is produced and behaves, elements that are essential for the correct design of music rehearsal spaces and performance venues. Acoustics is also essential for the design and manufacture of musical instruments. The word itself derives from the Greek word acoustikos which means “of hearing.” People who work in the field of acoustics generally fall into one of two groups: Acousticians, those who study the theory and science of acoustics, and acoustical engineers, those who work in the area of acoustic technology. This technology ranges from the design of rooms, such as classrooms, theatres, arenas, and stadiums, to devices such as microphones, speakers, and sound-generating synthesizers, to the design of musical instruments like strings, keyboards, woodwinds, brass, and percussion.

Sound and Sound Waves

As early as the sixth century BCE (500 years before the birth of Christ), Pythagoras reasoned that strings of different lengths could create harmonious (pleasant) sounds (or tones) when played together if their lengths were related by certain ratios. Concurrent sounds in ratios of two to three, three to four, four to five, etc. are said to be harmonious. Those not related by harmonious ratios are generally referred to as noise. About 200 years after Pythagoras, Aristotle (384-322 BCE) described how sound moves through the air—like the ripples that occur when we drop a pebble in a pool of water—in what we now call waves. Sound is basically the mechanical movement of an audible pressure wave through a solid, liquid, or gas. In physiology and psychology, sound is further defined as the recognition of the vibration caused by that movement. Sound waves are the rapid movements back and forth of a vibrating medium—the gas, water, or solid—that has been made to vibrate.

1.3.3 Properties of Sound: Pitch

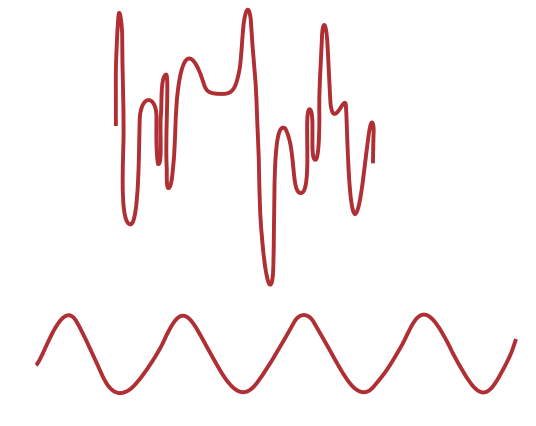

Another element that we tend to look for in music is what we call “definite pitch.” A definite pitch is a tone that is composed of an organized sound wave. A note of definite pitch is one in which the listener can easily discern the pitch. For instance, notes produced by a trumpet or piano are of definite pitch. An indefinite pitch is one that consists of a less organized wave and tends to be perceived by the listener as noise. Examples are notes produced by percussion instruments such as a snare drum.

Numerous types of music have a combination of definite pitches, such as those produced by keyboard and wind instruments, and indefinite pitches, such as those produced by percussion instruments. That said, most tunes are composed of definite pitches, and, as we will see, melody is a key aspect of what most people hear as music.

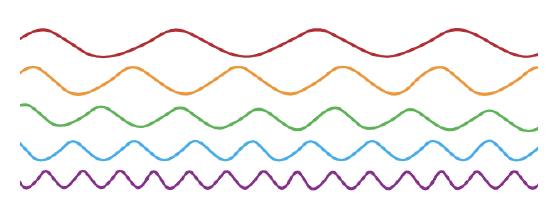

The sound waves of definite pitches may come in many frequencies.

Frequency refers to the repetitions of a wave pattern over time and is normally measured in Hertz or cycles per second (cps). Humans normally detect types of sound called musical tones when the vibrations range from about twenty vibrations per second (anything slower sounds like a bunch of clicks) to about 20,000 vibrations per second (anything faster is too high for humans to hear.) Watch the first five minutes of this excellent explanation of how different types of sounds result from the combination of the partials above the basic tone. In actuality, all sounds result from different variations of this process, as it naturally occurs in our environment.

Ex. 1.1: The Audio Kitchen; Sawtooth and Square Waves (2012)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=A1gwC8Y0yMU

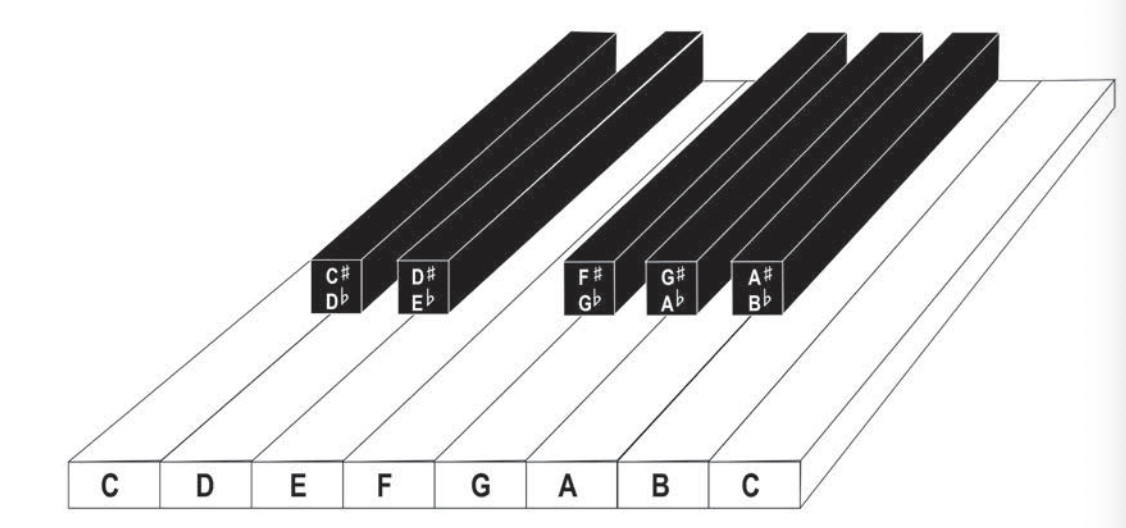

In the Western world, musicians generally refer to definite pitches by the “musical alphabet.” The musical alphabet consists of the letters A-G, repeated over and over again (…ABCDEFGABCDEFGABCDEFG…), as can be seen from this illustration of the notes on a keyboard. These notes correspond to a particular frequency of the sound wave. A pitch with a sound wave that vibrates 440 times each second, for example, is what most musicians would hear as an A above middle C. (Middle C simply refers to the note C that is located in the middle of the piano keyboard.) As you can see, each white key on the keyboard is assigned a particular note, each of which is named after the letters A through G. Halfway between these notes are black keys, which sound the sharp and flat notes used in Western music. This pattern is repeated up and down the entire keyboard.

SIDEBAR: How Waves Behave

- Reflection – sound waves reflect off of hard surfaces

- Absorption – sound waves are absorbed by porous surfaces

- Amplitude – refers to how high a wave appears on an oscilloscope; i.e., how much energy it has and therefore how loud it is

- Frequency – refers to how many times a wave vibrates each second. This vibrating speed is measured using cycles per second (cps) or the more modern Hertz (Hz)

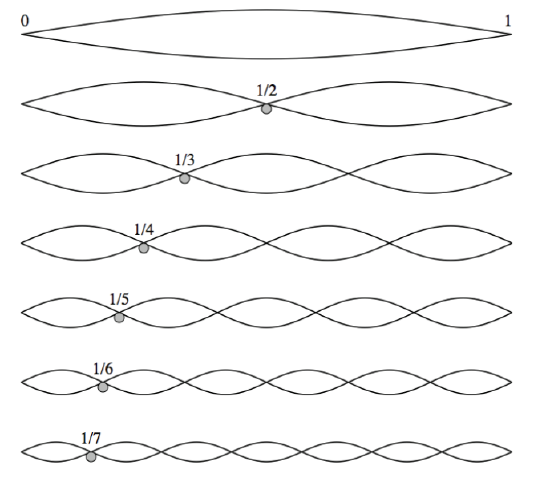

When a sound wave is generated, it often generates other waves or ripple effects, depending on the medium through which it travels. When a string of a certain length is set into motion, for example, its waves may also set other strings of varying lengths into motion.

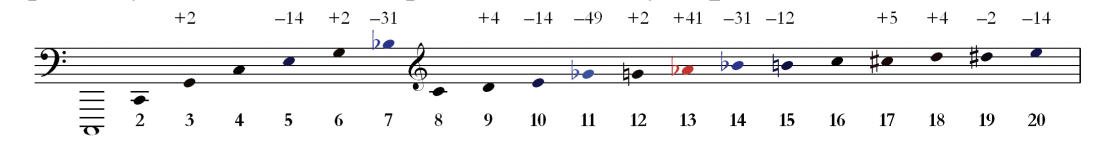

The vibration with the lowest frequency is called the fundamental pitch. The additional definite pitches that are produced are called overtones, because they are heard above or “over” the fundamental pitch (tone). Our musical alphabet consists of seven letters repeated over and over again in correspondence with these overtones. Please see Figure 1.3.6 for the partials for the fundamental pitch C:

To return to the musical alphabet: the first partial of the overtone series is the loudest and clearest overtone heard “over” the fundamental pitch. In fact, the sound wave of the first overtone partial is vibrating exactly twice as fast as its fundamental tone. Because of this, the two tones sound similar, even though the first overtone partial is clearly higher in pitch than the fundamental pitch. If you follow the overtone series, from one partial to the next, eventually you will see that all the other pitches on the keyboard might be generated from the fundamental pitch and then displaced by octaves to arrive at pitches that move by step (refer to Figure 1.3.6).

Watch these two videos for an excellent explanation of the harmonic series from none other than Leonard Bernstein himself, famous conductor of the New York Philharmonic and composer of the music of West Side Story.

Ex. 1.2: The Harmonic Series

Bernstein: The Harmonic Series / Norton Lectures

The distance between any two of these notes is called an interval. On the piano, the distance between two of the longer, white key pitches is that of a step. The longer, white key pitches that are not adjacent are called leaps. The interval between C and D is that of a second, C and E that of a third, the interval between C and F that of a fourth, the interval between C and G that of a fifth, the interval of C to A is a sixth, the interval of C to B is a seventh, and the special relationship between C and C is called an octave.

1.3.4 Other Properties of Sound: Dynamics, Articulation, and Timbre

The volume of a sound is referred to as dynamics; it corresponds with the amplitude of the sound wave. The articulation of a sound refers to how it begins and ends, for example, abruptly, smoothly, gradually, etc. The timbre of a sound is what we mean when we talk about tone color or tone quality. Because sound is somewhat abstract, we tend to describe it with adjectives typically used for tactile objects, such as “gravelly” or “smooth,” or adjectives for visual descriptions, such as “bright” or “metallic.” It is particularly affected by the ambiance of the performing space, that is, by how much echo occurs and where the sound comes from. Timbre is also shaped by the equalization (EQ), or balance, of the fundamental pitch and its overtones.

The video below is a great example of two singers whose voices have vastly different timbres (as well as styles). How would you describe Ed Sheeren’s voice? Perhaps you would call it “nasal" or “sinewy.” How would you describe Andrea Bocelli’s voice? Perhaps it could be called “centered” or “open.”

Ex. 1.3: Ed Sheeran - "Perfect Symphony" featuring Andrea Bocelli