6.5: Organizing Forces - Symmetry and Centricity

- Page ID

- 61976

Centricity in post-tonal music can be established in a variety of ways, often simply by emphasis. When a particular pitch-class is regularly the lowest, highest, loudest, or longest in a passage, that pitch-class becomes something like a tonic.

Apart from these means, pitch and/or pitch-class symmetry represents a novel method by which post-tonal composers created centricity in their music. And the study of symmetry in general takes us far afield of the compositional techniques generally associated with common-practice tonal music.

Pitch Symmetry

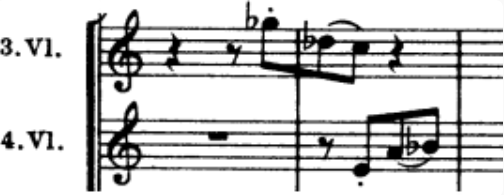

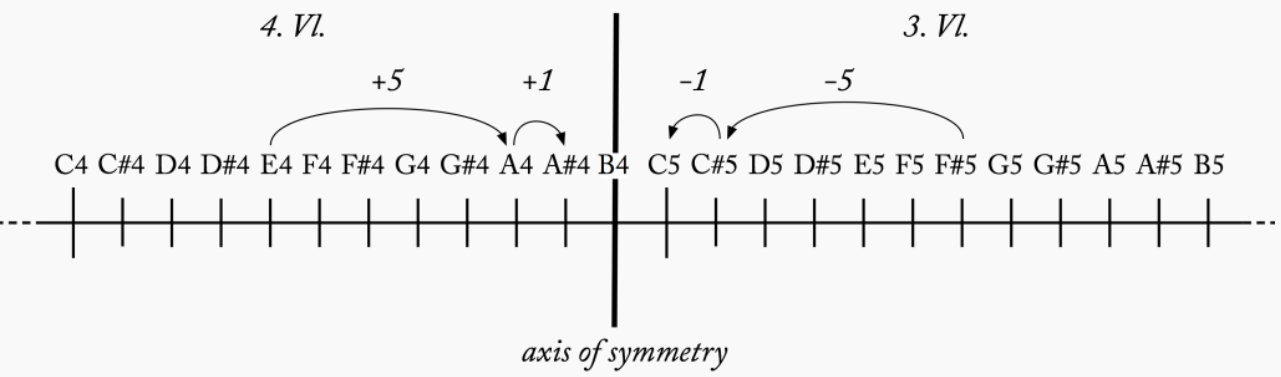

Think of pitch symmetry in terms of a musical “mirror.” In the passage below — from Bartók’s Music for Strings, Percussion, and Celesta — the third violin (3. Vl.) plays a gesture comprising two descending pitch intervals: –5 followed by –1. That is mirrored by the fourth violin (4. Vl), who plays the same pitch intervals, only ascending: +5 followed by +1. Below the example, I’ve diagrammed the gestures in pitch space. And you can that when combined the two gestures create a symmetrical arch.

Bartók, Music for Strings, Percussion, and Celesta

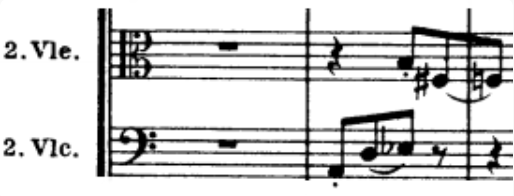

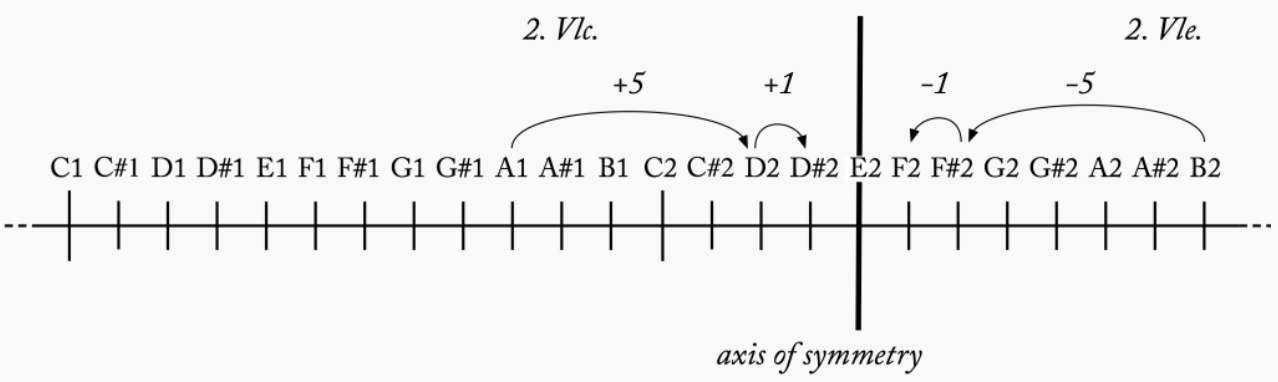

Pitch symmetry always implies an axis of symmetry. Maintaining our mirror metaphor, this is the place in pitch space where the mirror exists. In the case of the example above, the mirror is located at B4. Below, you’ll see the same gesture in the lower strings. The pitch-space line shows that it has a different axis of symmetry — around E2.

Pitch-Class Symmetry

Pitch-class symmetry is very similar to pitch symmetry, but understood in pitch-class space. Below you’ll see another passage from the same piece by Bartók. As above the lower strings have an ascending gesture that mirrors the descending gesture in the upper strings.

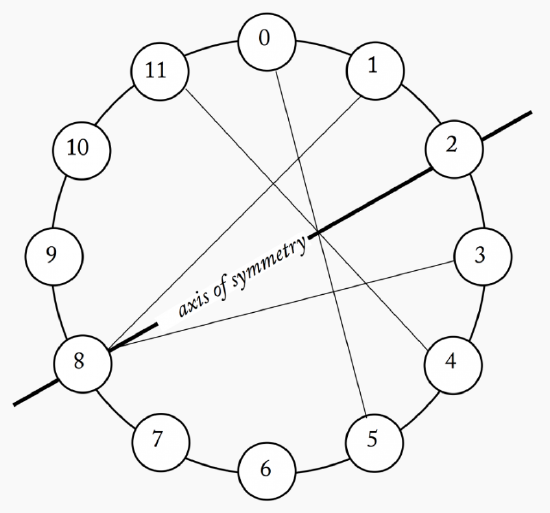

Mapping this on the pitch-class circle shows the passage’s pitch-class symmetry. Look at this circular diagram very carefully. You’ll notice that the passage is pitch-class symmetrical around both 2 and 8. Unlike pitch space, pitch-class axes are always located at two different points in the pitch-class circle.