2.1: Romanticism

- Page ID

- 82970

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Unit 1: Romanticism

Unit 1: Romanticism Although the publication of Wordsworth's Lyrical Ballads in 1798 is often heralded as the formal start of Romanticism, the roots of the movement began earlier. The Enlightenment, or Age of Reason, had embraced the power of rational thought and the scientific method to advance society in an orderly fashion. Romanticism, however, heralded a more individual approach, often guided by strong emotions and some type of spiritual insight. According to Romantics, deeper understanding of the world was achieved through intuition and emotional connections, rather than reason. In literature, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe was one of the early proponents of the Storm and Stress (Sturm und Drang ) period, which rejected the Enlightenment's focus on reason in favor of strong emotions and the value of the individual. Goethe's The Sorrows of Young Werther (1774) is a classic Storm and Stress novel, with a protagonist driven by his extreme emotions. In politics, the revolutions of the time were driven by certain Enlightenment concepts that would be important to later Romanticism: in particular, the idea of natural rights, which was discussed by politicians, philosophers, and writers alike. John Locke asserted that human beings have the right to life, liberty, and property, and Francis Hutcheson posited the difference between alienable and unalienable rights. Thomas Jefferson used these ideas more or less directly in his writings. Rather than owing loyalty to a monarch, the Declaration of Independence (1776) asserts that human beings have rights from God and the laws of nature that cannot be taken away by an earthly ruler. The French Revolution and the rise of Napoleon Bonaparte (a fan of The Sorrows of Young Werther who claimed to have read the novel many times) also challenged established authority. Romanticism, as practiced by Wordsworth, is a natural outgrowth of those revolutionary ways of thinking. If human rights are derived from "the laws of nature and of nature's God" (Jefferson), then it makes sense that Wordsworth sees God's presence in nature. In his poetry, nature represents truth, purity, and innocence, so the poet praises children and women as closer to God, because he sees them as closer to innocence. Wordsworth also highlights how the "other" revolution—namely, the industrial revolution—had begun to affect society in increasingly negative ways. Wordsworth contrasts the pollution of urban areas with pristine nature, characterizing modern urban life as a loss of connection to spiritual values. Wordsworth, however, is only one of many voices in Romanticism. If Wordsworth saw women as childlike in their innocence, other writers disputed whether that was, in fact, accurate (or desirable). Women responded to the debate about the rights of man by discussing the rights of women, leading to works such as The Declaration of the Rights of Women (1791), by Olympe de Gouges, and A Vindication of the Rights of Women (1792), by Mary Wollstonecraft. If nature could be a source for inspired reflection in Wordsworth, it could also be dangerous. Coleridge's "Kubla Khan," which touches on the Romantic idea of poet as genius at the end, notes the thin line between genius and madness. Exceptional individuals as protagonists are the norm in Romanticism, in part from the (early) admiration for Napoleon Bonaparte. The admiration for Bonaparte, however, began to fade among many Romantic poets as he became a part of the monarchy and a more traditional figure of authority. One type of exceptional individual, the Romantic hero, has either rejected society or been rejected, and therefore is no longer constrained by society's rules (with the reminder that a Romantic hero is not necessarily romantic, but rather a product of Romanticism). Romantic heroes tend to be self-centered and arrogant, but are capable of compassion and even self-sacrifice, in some cases. A Byronic hero is a subset of Romantic hero, named for the poet Byron, who was described as "mad, bad, and dangerous to know." The distinction between the two types can get murky, since the Byronic hero is in some ways simply a bit more dangerous and alienated than the Romantic hero (in fact, characters such as Heathcliff in Emily Brontë's Wuthering Heights and Faust in Goethe's Faust have been called both by various literary scholars). Byronic heroes are more likely to have some guilty secret in the past, or some unnamed crime that is never revealed, which drives the characters' actions, and they are more likely to end tragically. There were critiques of Romanticism even during the movement. In Mary Shelley's Frankenstein, she questions both Enlightenment views of science and Romanticism's view of the hero. The first narrator, Robert Walton, fails miserably to advance scientific exploration in the Arctic, while risking the lives of others. Similarly, Victor Frankenstein's self-absorbed behavior slowly destroys everyone around him. Victor's passivity and silence become more and more criminal as the novel progresses. Mary Shelley began the novel while she and her future husband, the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley, were spending time with Byron, which makes her critical analysis even more intriguing. Victor Frankenstein becoming disgusted at his creation. Illustration from the frontispiece of the 1831 edition of Frankenstein by Mary Shelley. Steel engraving by Theodore Von Holst. License: Public Domain.

Victor Frankenstein becoming disgusted at his creation. Illustration from the frontispiece of the 1831 edition of Frankenstein by Mary Shelley. Steel engraving by Theodore Von Holst. License: Public Domain.

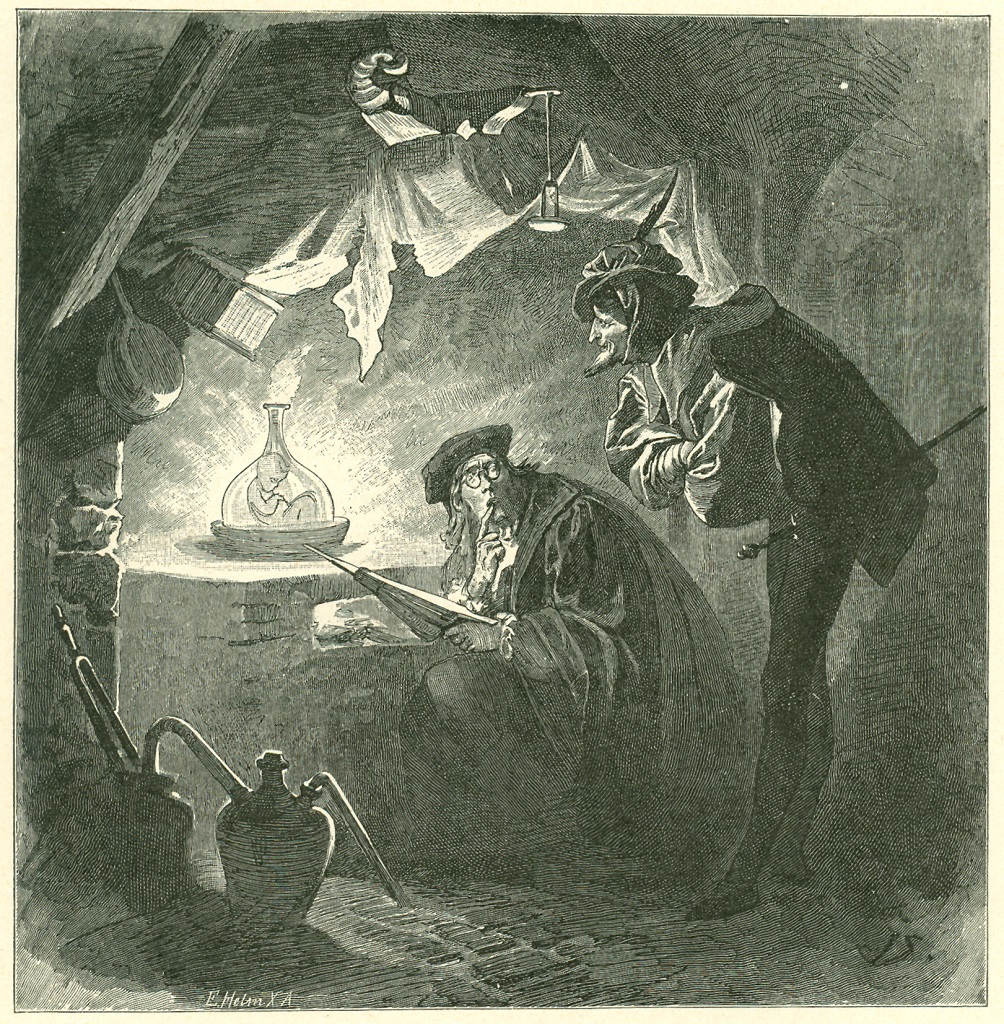

Homunculus in the phial. Famulus Wagner and Mephistopheles. Illustration to Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Faust. Part Two, Act II, Laboratory. Illustrated by Franz Xaver Simm. License: Public Domain.

Homunculus in the phial. Famulus Wagner and Mephistopheles. Illustration to Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Faust. Part Two, Act II, Laboratory. Illustrated by Franz Xaver Simm. License: Public Domain.