1.3: Medieval Drama

- Page ID

- 76665

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Learning Objectives

- Define and explain the purpose of mystery plays and morality plays.

- Identify an example of a mystery play and of a morality play.

The long-held scholarly account of medieval drama asserts that the religious drama of the Middle Ages grew from the Church’s services, masses conducted in Latin before a crowd of peasants who undoubtedly did not understand what they were hearing. This idea certainly fits with the concept of church architecture in its cruciform shape to picture the cross, its stained glass windows to portray biblical stories, and other features designed to convey meaning to an illiterate population. Many scholars suggest that on special days in the liturgical year, the clergy would act out an event from the Bible, such as a nativity scene or a reenactment of the resurrection. Gradually, these productions became more complex and moved outside to the churchyard and then into the village commons.

Other scholars, however, suggest a different origin of medieval drama, claiming that it grew parallel to but outside of Church services which continued with their dramatic features as part of the mass.

Mystery Plays

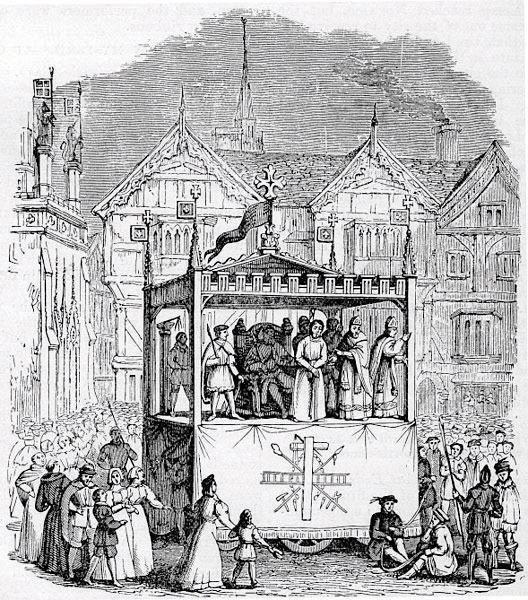

Mystery plays depict events from the Bible. Often mystery plays were performed as cycle plays, a sequence of plays portraying all the major events of the Bible, from the fall of Satan to the last judgment. Some play cycles were performed by guilds, each guild taking one event to dramatize. One of the most famous of the play cycles, the York mystery plays, is still performed in the English city of York. Records from the Chester cycle, also still performed, list which guilds were involved and which plays each guild presented. In a few places, such as York, the cycles were performed on pageant wagons that moved on a pre-determined route through the city. By staying in the same place, the audience could see each individual play as the wagon stopped and the actors performed before moving on to perform again at the next station. Four English cities were particularly noted for their cycles of mystery plays: Chester, York, Coventry, and Towneley (referred to as the Wakefield plays). Dennis G. Jerz, Associate Professor of English at Seton Hall University, created a simulation of the path of the pageant wagons through York, showing the route and the order of the plays.

The Second Shepherds’ Play

One of the most well-known of the mystery plays is The Second Shepherds’ Play, part of the Wakefield cycle. The play blends comic action, serious social commentary, and the religious story of the angelic announcement of Christ’s birth to shepherds. At the beginning of the play, three shepherds complain of the injustices of their lives on the lowest rung of the medieval social ladder. When another peasant steals one of their lambs, the thief and his wife try to hide the animal by disguising it as their infant son; thus, an identification of a new-born son with the symbolic lamb foreshadows the biblical story. At the end of the play, the religious message becomes clear when angels announce the birth of Christ.

The text of The Second Shepherds’ Play is available on the following sites:

- Bibliotheca Anglica Middle English Literature. Bibliotheca Augustana. University of Augsburg. http://www.hs-augsburg.de/~harsch/anglica/Chronology/15thC/WakefieldMaster/wak_shep.html

- Corpus of Middle English Prose and Verse. University of Michigan. http://quod.lib.umich.edu/cgi/t/text/text-idx?c=cme;idno=Towneley;rgn=div1;view=text;cc=cme;node=Towneley%3A13

- “The Second Shepherds’ Play.” The Electric Scriptorium. University of Calgary, Canada. people.ucalgary.ca/~scriptor/towneley/plays/second.html

- “The Second Shepherds’ Play.” Ernest Rhys, ed. Project Gutenberg. http://www.gutenberg.org/files/19481/19481-h/19481-h.htm

Morality Plays

Morality plays are intended to teach a moral lesson. These plays often employ allegory, the use of characters or events in a literary work to represent abstract ideas or concepts. Morality plays, particularly those that are allegorical, depict representative characters in moral dilemmas with both the good and the evil parts of their character struggling for dominance. Similar to mystery plays, morality plays did not act out events from the Bible but instead portrayed characters much like the members of the audience who watched the play. From the characters’ difficulties, the audience could learn the moral lessons the Church wished to instill in its followers.

One of the most well known of extant morality plays is Everyman. In this morality play, God sends Death to tell Everyman that his time on earth has come to an end.

The text of Everyman is available on the following sites:

- Everyman. Corpus of Middle English Prose and Verse. University of Michigan. http://quod.lib.umich.edu/cgi/t/text/text-idx?c=cme;cc=cme;view=toc;idno=Everyman

- Everyman. Ernest Rhys, ed. Project Gutenberg. http://www.gutenberg.org/files/19481/19481-h/19481-h.htm

- Everyman. Renascence Editions. University of Oregon. http://www.luminarium.org/renascence-editions/everyman.html

- Everyman. W. Carew Hazlitt, ed. Project Gutenberg. http://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/9050/pg9050.html

Key TakeawayS

Medieval drama provided a method for the Church to teach a largely illiterate population.Two primary forms of medieval drama were the mystery play and the morality play.

Resources: Medieval Drama

History of Medieval Drama

- “The Dawn of the English Drama.” Theater Database. rpt. from Truman. J. Backus. The Outlines of Literature: English and American. New York: Sheldon and Company, 1897. 80–84. http://www.theatredatabase.com/medieval/dawn_of_the_english_drama.html

- “Drama of the Middle Ages.” Theater Database. http://www.theatredatabase.com/medieval/medieval_theatre_001.html

- “The Medieval Drama.” Theater Database. rpt. from Robert Huntington Fletcher. A History of English Literature for Students. Boston: Richard G. Badger, 1916. 82–91. http://www.theatredatabase.com/medieval/medieval_drama_001.html

- “The Medieval Drama.” TheatreHistory.com. rpt. from Brander Matthews. The Development of the Drama. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1912. 107–146. http://www.theatrehistory.com/medieval/medieval001.html

- “Medieval Drama: Myths of Evolution, Pageant Wagons, and (lack of) Entertainment Value.” Carolyn Coulson-Grigsby. The ORB: Online Reference Book for Medieval Studies. www.the-orb.net/non_spec/missteps/ch5.html

- “Medieval Drama: An Introduction of Middle English Plays.” Anniina Jokinen. Luminarium. rpt. from Robert Huntington Fletcher. A History of English Literature. Boston: Richard G. Badger, 1916. 85–91. http://www.luminarium.org/medlit/medievaldrama.htm

- “Middle English Plays.” Anniina Jokinen. Luminarium. Links to an introduction of medieval drama in England, texts of plays, and scholarly information on medieval drama. http://www.luminarium.org/medlit/plays.htm

Mystery Plays

- “The Chester Guilds.” Chester Mystery Plays. History including a pop-up list of guilds responsible for specific plays in the Chester cycle. www.chestermysteryplays.com/history/history/morehistory.html

- “The Collective Story of the English Cycles.” Theatre Database.com. rpt. from Charles Mills Gayley. Plays of Our Forefathers. New York: Duffield & Co., 1907. 118–24. http://www.theatredatabase.com/medieval/collective_story_of_the_english_cycles.html

- “Medieval Church Plays.” TheatreHistory.com. rpt. from Alfred Bates, ed. The Drama: Its History, Literature and Influence on Civilization, Vol. 7. London: Historical Publishing Company, 1906. 2–3, 6–10. http://www.theatrehistory.com/medieval/mysteries001.html

- “Mysteries and Pageants in England.” TheatreHistory.com. rpt. from Martha Fletcher Bellinger. A Short History of the Drama. New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1927. 132–7. http://www.theatrehistory.com/medieval/mysteries002.html

- “Popular English Drama: The Mystery Plays.” L.D. Benson. The Geoffrey Chaucer Page. Harvard University. www.courses.fas.harvard.edu/~chaucer/special/litsubs/drama/

- Simulation of York Corpus Christi Play. Dennis G. Jerz. An interactive map that illustrates the progression of the plays through the city of York. http://jerz.setonhill.edu/resources/PSim/applet/index.html

- “What Are the York Mystery Plays?” York Mystery Plays. A brief history of the York plays and information about current productions. http://www.yorkmysteryplays.org/default.asp?idno=4

- “What’s the Mystery?: Medieval Miracle Plays.” Folger Shakespeare Library. www.folger.edu/template.cfm?cid=2514

- “The York Plays.” Chester N. Scoville and Kimberley M. Yates. Records of Early English Drama (REED): Centre for Research in Early English Drama. University of Toronto. www.reed.utoronto.ca/yorkplays/york.html#pag

Text of The Second Shepherds’ Play

- Bibliotheca Anglica Middle English Literature. Bibliotheca Augustana. University of Augsburg. http://www.hs-augsburg.de/~harsch/anglica/Chronology/15thC/WakefieldMaster/wak_shep.html

- Corpus of Middle English Prose and Verse. University of Michigan. http://quod.lib.umich.edu/cgi/t/text/text-idx?c=cme;idno=Towneley;rgn=div1;view=text;cc=cme;node=Towneley%3A13

- “The Second Shepherds’ Play.” The Electric Scriptorium. University of Calgary, Canada. people.ucalgary.ca/~scriptor/towneley/plays/second.html

- “The Second Shepherds’ Play.” Ernest Rhys, ed. Project Gutenberg. http://www.gutenberg.org/files/19481/19481-h/19481-h.htm

Morality Plays

- “Allegory.” The University of Victoria’s Hypertext Writer’s Guide. Department of English. University of Victoria. web.uvic.ca/wguide/Pages/LTAllegory.html

- Everyman. Anniina Jokinen. Luminarium. Links to an introduction to Everyman, sites including the text of the play, and scholarly information about the play. http://www.luminarium.org/medlit/everyman.htm

- “Moralities, Interludes and Farces of the Middle Ages.” Moonstruck Drama Bookstore. rpt. from Martha Fletcher Bellinger. A Short History of the Drama. New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1927. 138–44. http://www.imagi-nation.com/moonstruck/spectop006.html

- “The Morality Plays.” Drama. Internet Shakespeare Editions. University of Victoria. internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/SLT/drama/moralities.html

Text of Everyman

- Everyman. Corpus of Middle English Prose and Verse. University of Michigan. http://quod.lib.umich.edu/cgi/t/text/text-idx?c=cme;cc=cme;view=toc;idno=Everyman

- Everyman. Ernest Rhys, ed. Project Gutenberg. http://www.gutenberg.org/files/19481/19481-h/19481-h.htm

- Everyman. Renascence Editions. University of Oregon. http://www.luminarium.org/renascence-editions/everyman.html

- Everyman. W. Carew Hazlitt, ed. Project Gutenberg. http://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/9050/pg9050.html

Video

- A Brief Introduction to the York Mystery Plays 2010. Information about the modern production of the York cycle. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8nyFLOlEupM

- “From an Ill-Spun Wool: The Second Shepherds' Play and Early English Theater.” Folger Shakespeare Library. Podcast lectures about the staging of the play and the origin of the play. www.folger.edu/template.cfm?cid=2615

- The History of the Theatre: Medieval Theatre. Richard Parker. Theatre Arts Instructor, Columbia Gorge Community College. Lecture on early drama from an online theater history class at Columbia Gorge Community College. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QxdDoUoFQhM

- “Noah’s Deluge, Part 2.” Chester Mystery Plays. A video of one of the 2009 Chester plays. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PxQ6sihBKmU&p=1D92A5E5AEF6B6A5&playnext=1&index=3