8.2: Writing as a Process - Breaking it Down

- Page ID

- 15903

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)For many students, approaching a writing assignment can be overwhelming. They know that there are many tasks that must be completed, such as gathering information about the topic, forming a perspective on it, brainstorming ideas to be included in the paper, organizing those ideas, integrating the evidence, and articulating the argument with clarity and eloquence, not to mention accommodating the assigned format guidelines. This job is not unlike building a house. You look at the empty lot and imagine the beautiful house you want to build, but you know that the tasks necessary to get from nothing to the final product are many and varied. The prospect can certainly be overwhelming. Yet, any builder understands that the best approach to a big job like this one is breaking it down into a methodical and carefully scheduled process. In response to a challenging writing assignment, you are encouraged to do the same.

Let’s consider the writing assignment Bill originally received from his English 1102 instructor:

For this essay, write a literary analysis of Ernest Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises using a formalist 239 The Literary Analysis Essay approach. The essay should forward a specific perspective on the novel (articulated in your thesis), and the evidence for your argument should come from the novel itself. The essay should be three-four pages in length. Due date: February 3.

Bill remembers that in his high school senior English class, he once procrastinated on a major paper assignment and ended up writing the whole essay in one night. The result was a “D” on the paper and a tendency to experience writer’s block, which still plagued him all during his first semester of college. But he has one tool this second semester that he has not had before: his instructor’s handout on “Writing as a Process.” The literary analysis essay for this class is not due for three weeks, but he decides to review the handout now as a first step to avoiding writer’s block and another low grade. Here is the advice recommended in his instructor’s handout:

- Investigate the general topic; in this case, read the novel and make notes and annotations as you go.

- Brainstorm points of interest regarding what you’ve learned so far. As you brainstorm, do not try to write in full sentences or to organize your thoughts. Instead, simply write down everything that comes to mind.

- Read back over your notes and decide on a focus. Considering this focus, decide what you think about this topic, based on your observations so far. Form a perspective on the topic.

- Again considering your brainstorming notes, determine a very general organization for the major points on this topic. Once you have completed this basic outline, categorize all the leftover “smaller” items under the most relevant major points. If some items on your brainstorming page don’t seem relevant, mark through them. Keep only the items that fit your paper’s focus.

- With the paper topic and its major supporting points in mind, write a working thesis. This thesis is not set in stone yet, but it will help you stay on track as you move forward.

- Go back to your materials on the general topic now—in this case, comb through your notes on the novel, annotations, and highlighted passages. Would any of these words, ideas, and/ or passages make effective evidence to develop one or more of your major points? As you find fruitful items, jot down a quote, summary, or paraphrase of each item, along with the page number of the novel where you found it. Make a note to yourself indicating which major point each item supports.

- Revise your paper outline now to include not only the working thesis and the major points, but also the pieces of evidence that will go under each major point.

- Begin drafting the paper. If the introduction does not come quickly, skip it. Keep your working thesis in mind and write out the major sections of your paper which support that thesis.

- Now go back to the introduction. Consider your audience. How are you trying to alter your audience’s perspective on the novel with this paper? How can you use the introduction to (a) draw your reader’s interest to your new way of looking at the novel and (b) lay the groundwork for your argument? The introduction should accomplish these goals. Write your conclusion with similar goals in mind. This is your last chance to persuade your reader that your perspective is convincing and important. How can you leave your reader with a strong and lasting impression?

- Once you have drafted the entire essay, start at the beginning and revise. Pay particular attention to coherence during this phase. In a coherent paper, everything in the essay promotes its central purpose. During this phase, you may want to clarify and strengthen the relationships among ideas with transition words and explanations. A coherent paper exhibits a certain tightness that produces the desired impact on the reader. Imagine that you are reading the paper aloud to an actual audience of fellow students who have their own values and opinions. How can you shape the prose to (1) keep their attention, (2) clearly and persuasively convey your case, and (3) convince these readers that your perspective is a valuable one?

- Final revision phase: Read through the essay as many times as you need to, checking grammar and spelling and giving the language its final polish. Read it aloud again, this time slowly, to be sure that the essay sounds as eloquent as you intended for it to.

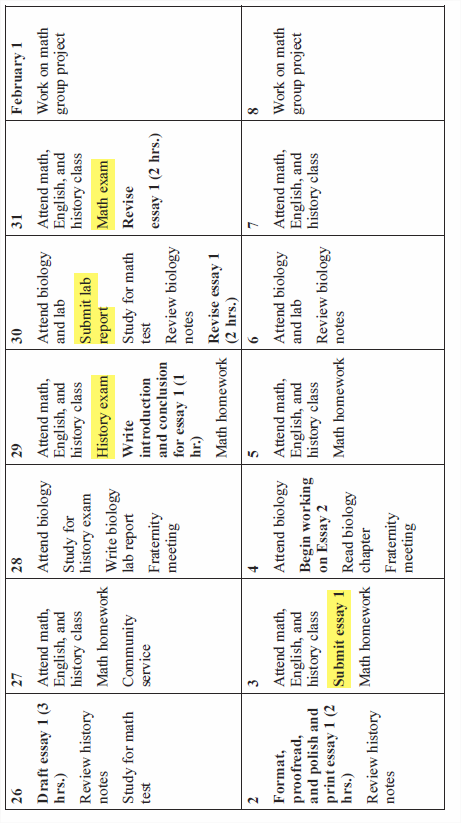

- Be sure that the essay follows the format guidelines and is ready for submission. In class, after handing out this sheet, Bill’s instructor told the students to take out their datebooks. She told the students to consult their schedules and assign “dummy” dates for each item on the task list. Here is how Bill divided up his time for addressing the tasks necessary for completing the paper:

To some students, the idea of working for an entire three weeks on a three to four page essay might seem extreme. Yet, anyone who writes for a living will attest that all of these tasks are necessary for a high quality product. Professional writers may allocate their time a bit differently, perhaps working for eight or nine hours in one day on a single project, and undoubtedly they gain speed over time at completing each stage of the process. Even so, they understand that for a product with the desired impact, one must spend time planning and crafting the piece. Since students are usually taking other classes in addition to English, and must often hold down jobs and fulfill personal obligations, Bill’s Essay 1 plan is much more likely to work out than a twenty-hour writing marathon beginning two days before the paper’s due-date. Notice that Bill did not schedule any Essay 1 tasks for January 18, 24-25, 27-28, and February 1. Looking ahead in his date book, he realized that he has fraternity events on January 18 and 27, and he wants to save time on the other dates to join his family for his grandmother’s birthday celebration, as well as to study intensively for a history test and work with a group on a math project.

As Bill discovers in carrying out his plans, he experiences much less stress than before as he tackles the “small” daily writing tasks he has assigned himself. On the day he does his brainstorming for Essay 1, he does not feel pressured by the fact that he still needs to write and revise the essay—he knows the time-slots for those tasks are already carved out in his calendar and he will be able to address those items on the designated dates. Let’s look at the products of two of Bill’s writing process tasks:

Brainstorming Sheet:

- the Sun Also Rises—Why this title?

- Jake seems tough but does cry and feel bad often.

- Brett shaky—an alcoholic?

- Jake’s wound—mysterious, his groin

- Bullfights—gory but exciting; but gets ruined for Jake

- World War I

- Party-time all the time

- But the characters don’t always like each other—Jake and Robert’s

- fight, Mike can’t stand Robert, Brett sleeps with three different guys

- 9. Brett and Jake—the status of their relationship?

- Mike is bankrupt

- Jake is a journalist

- Jake goes to church but can’t focus

- Brett says she can’t pray

- Loss of faith

- Bill seems less messed up than the rest

- Romero's innocence and youth

- Montoya—aficionado, wants to protect Romero

- The loud music and fireworks

- The ending—what will happen now?

Jake’s wound; everyone’s wounds Loss of faith and hope More general—is the novel optimistic or not?

Essay 1 Working Thesis and Basic Outline

Working thesis: The novel is not optimistic because Hemingway is emphasizing how badly war can damage our world, as it has for these characters. Focus on certain metaphors to prove that this is the novel’s message.

I. Jake’s wound

a. What it reveals about Jake

i. Physical effects

ii. Psychological effects

b. What it says as a metaphor for the other characters’ “injuries”

i. They avoid really talking

i. They stay drunk all the time

II. Bull fight—One of the last “sacred” things for Jake before it

gets sullied

a. Montoya

b. Romero

c. Like loss of faith in everything else

In Chapter 5, we saw Bill’s final draft of the essay. He did much work between composing the tentative outline, above, and completing the full, revised essay. With his task-list broken down and carefully scheduled, he was able to give each phase the attention and time necessary to produce a well-argued final essay.