3.1: Advanced Searching Techniques Details

- Page ID

- 100026

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Advanced Searching

All of the searching we've done in this class and that you probably do on a regular basis is general keyword searching. But, there are many tips and tricks hidden in databases and Internet search engines that can help you become an advanced-level searcher. That's what the next several tabs are about and you'll have a chance to practice some of these techniques in this week's assignments.

Boolean Operators

One way to limit a database search is to use Boolean operators; words you can add to a search to narrow or broaden your search results.

Boolean operators are the words And, Or, and Not. You can usually find these words and the searching technique in the advanced search query area of a database. You can still use Boolean operators without being in an advanced search screen, but, this is important: in most databases, in order for Boolean operators to work properly in a keyword search box, the operators must be in all caps. That is why I have kept the operators in all caps throughout this section, so that you understand the importance of remembering to use all caps when using the Boolean operators searching technique.

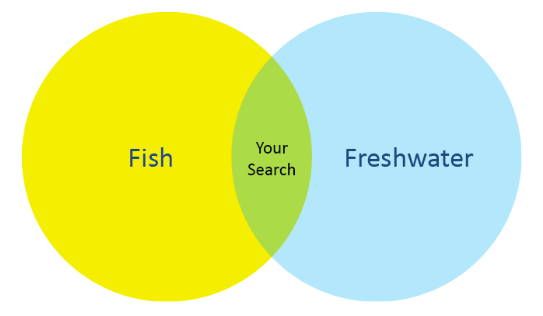

AND

AND will narrow your search. For example, if you are interested in fresh water fishing you would enter the terms “fish and freshwater.” Your results would then include records that contained both of these words. In the image below, your results are represented by the green area where the two circles intersect.

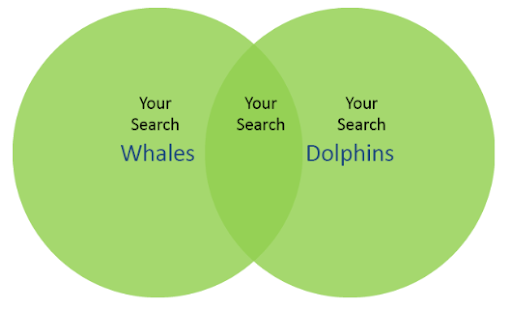

OR

The Boolean operator OR will broaden your search and is usually used with synonyms (different words that have the same meaning). If you are interested in finding information on mammals found in the Atlantic Ocean, you could enter the terms “whales or dolphins.”

The circles below represent the OR search. All of the records that contain one, or another, or both of your search terms will be in your results list.

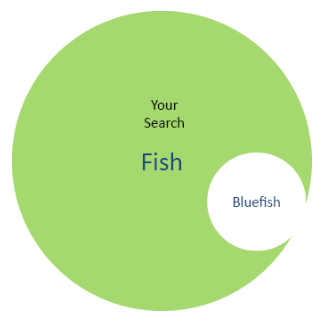

NOT

The Boolean operator NOT will eliminate a term from your results. If you were looking for information on all Atlantic Ocean fish except Bluefish, you would enter “fish not bluefish.”

The larger green circle represents the results that you would retrieve with this search. Notice how Bluefish is excluded from the results.

Remember Sarah and her team researching women painters from last week? Let's apply Boolean operators to Sarah and her team's research. They've started their research by looking for sources about the women creating Impressionist art and they've identified two search strings:

-

women painters

-

women artists

They could do two separate searches by typing one or the other of the search strings into the search box of whatever tool they are using, but they'd end up with two separate result lists and have the added headache of trying to identify unique items from the lists.

They could also lump everything together and search on the phrase:

-

women painters AND women artists

But once you understand Boolean operators, that last strategy won’t make as much sense as it seems to.

There are three Boolean operators: AND, OR, and NOT.

AND is used to get the intersection of all the terms you wish to include in your search. With this example:

women painters AND women artists

Sarah's team is asking the database to retrieve both of those search strings, meaning all the results would include women painters AND women artists. If a source only has one string, it won’t show up in the results.

This isn't what the team had in mind. They are interested in both artists and painters, but because they don't know which term might be used, they want to search both.

Instead, OR would be a better choice.

OR is used when you want at least one of the terms to show up in the search results. If both do, that’s fine too, but it isn’t a condition of the search. The OR Boolean operator makes a lot more sense for this search:

women painters OR women artists

Now, the team could get fancy with this search, and use both AND as well as OR:

women AND (painters OR artists)

The parentheses mean that these two concepts, painters and artists, should be searched as a unit, and the search results should include all items that use one word or the other. The results will then be limited to those items that contain the word women.

When using parentheses for appropriate searches, make sure that the items contained within those parenthesis are related in some way. With OR, as in the previous example, it means either of the terms will work. With AND, it means that both terms will appear in the source.

Try this out on your own. Type both of these searches in Google Scholar and compare the results (please note, you must capitalize OR when using it as a Boolean operator in Google products). Were they the same? If not, can you determine what happened? Which result list looked better?

Truncation

Using Boolean operators isn’t the only way you can create more useful searches. This and the next few tabs will give you more tools for your searching tool box.

Look at this search string:

Entrepreneurs AND (adolescents OR teens)

You might expect that the items that are retrieved from the search can refer to entrepreneurs plural or entrepreneur singular. But, that's not always the case. Because computers are very literal, they usually look for the exact terms you enter.

While it is true that some search functions are moving beyond this model, you want to think about alternatives, just to be safe. In this case, using the singular as well as the plural form of the word might help you to find useful sources. Truncation, or searching on the root of a word and whatever follows, lets you do this.

So, if you modify the search string to this:

Entrepreneur* AND (adolescents OR teens)

You will get items that refer either to the singular or plural version of the word entrepreneur, but also entrepreneurship.

Look at these examples:

adolescen*

educat*

Think of two or three words you might retrieve when searching on these roots. It is important to consider the results you might get and alter the root if need be. An example of this is polic*. Would it be a good idea to use this root if you wanted to search on policy or policies? Why or why not? Try it out and see what you find.

In some cases, a symbol other than an asterisk is used. To determine what symbol to use, check the help section in whatever resource you are using. The topic should show up under the truncation or stemming headings.

Here is the same search terms worksheet you saw last week for Sarah's team, but with truncation acknowledged:

Machine readable text description of preceding graphic

OK - back to that polic* example. If you actually tried it, you'll find that police and policing also came up with this search. That's because policy, policies, police, and policing all have the same root. Keep this in mind when using truncation or wild card searching.

Phrase Searching

Phrase searches are particularly useful. If you put the exact phrase you want to search in quotation marks, you will only get items with those words as a phrase and not items where the words appear separately in a document, website, or other resource.

Your results will usually be fewer, although surprisingly, this is not always the case. Try these two searches in the search engine of your choice:

“essay exam”

essay exam

Was there a difference in the quality and quantity of results? Most databases allow phrase searching with the use of quotation marks. You'll also often see phrase searching when you enter an advanced search screen of a resource.

Advanced Web Searching

Advanced web searching allows you to refine your search query and prompts you for ways to do this. Consider the basic Google.com search box.

It is very minimalist, but that minimalism is deceptive. It gives the impression that searching is easy and encourages you to just enter your topic, without much thought. You certainly do get many results. But are they really good results? Simple search boxes aren't always the best way to go.

Advanced search screens show you many of the special searching options available to you to refine your search, and, therefore, get more manageable numbers of better items. Many web search engines and research databases include advanced search

screens. Advanced search screens will vary from resource to resource and from web search engine to research database, but they often let you search using

- Implied Boolean operators (for example, the “all the words” option is the same as using the Boolean and)

- Limiters for date, domain (.edu, for example), type of resource (articles, book reviews, patents)

- Field (a field is a standard element, such as title of publication or author’s name)

- Phrase (rather than entering quote marks)

Explore on Your Own

Go to the advanced search option in Google. Did you even know this page existed?!

Take a look at the options Google provides to refine your search. Compare this to the basic Google search box. One of the best ways you can become a better searcher for information is to use the power of advanced searches, either by using these more complex search screens or by remembering to use Boolean operators, phrase searches, truncation, and other options available to you in most search engines and databases.

While many of the text boxes at the top of the Google Advanced Search page mirror concepts already covered in this week's reading (for example, “this exact word or phrase” allows you to omit the quotes in a phrase search), the options for narrowing your results can be powerful.

You can limit your search to a particular domain (such as .edu for items from educational institutions) or you can search for items you can reuse legally (with attribution, of course!) by making use of the “usage rights” option.

However, be careful with some of the options, as they may excessively limit your results. If you aren’t certain about a particular option, try your search with and without using it and compare the results. If you use a search engine other than Google, check to see if it offers an advanced search option, many do.

The CRC Library has an online searching tips guide that covers all the searching tips included in this week's reading. You might want to bookmark this web address:

https://researchguides.crc.losrios.edu/searchtips

The guide will be available even after you have completed this course.

Scenario

Harry is feeling overwhelmed by one of his class assignments. Harry would have been happy if the assignment was to write a traditional research paper, but his professor has asked the class to solve a real life problem.

The professor has asked the class to imagine a small city undergoing a natural disaster such as a flood or a tornado. Each group in the class is required to plan a hypothetical information command center for this city. The professor explains that the government needs to obtain accurate, up-to-date information on the scope of the damage and injuries sustained due to the disaster. This information is vital for the city to be able to provide adequate emergency and medical assistance to its citizens.

Harry can see that this is an important function for any city in the midst of a crisis but he is not sure about where to get reliable information to help him construct a plan for the city.

Harry and his classmates do some brainstorming and decide to approach this assignment as if they were actually producing a research paper. Their first step will be to research recent disasters. They reason that this will provide some information about the way some cities have gathered information during disasters.

If an information gathering strategy worked for other cities, it will work for their hypothetical city. There certainly have been a lot of natural disasters recently, so it shouldn’t be too hard to find some information. Super Storm Sandy and Hurricane Irene are two events that have happened in recent years. The group starts to research Super Storm Sandy with Google and Wikipedia.

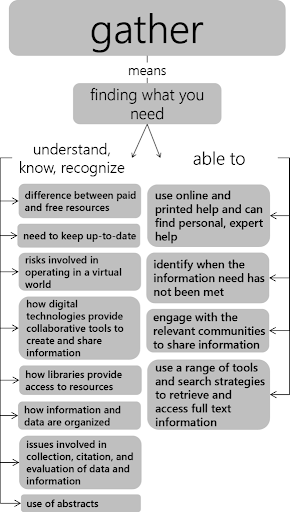

Gather Pillar

Harry and his classmates are engaging in the Gather pillar of the Seven Pillars of Information Literacy model. Just as municipalities needed to gather reliable information in order to provide vital services to their citizens, Harry and his group members need to gather information that will help them complete this assignment.

These information needs are components of the Gather pillar, which states that the information literate individual understands:

- How information and data are organized

- How libraries provide access to resources

- How digital technologies provide collaborative tools to create and share information

- The issues involved in collection of new data

- The different elements of a citation

- The use of abstracts

- The need to keep up to date

They are able to:

- Use a range of retrieval tools and resources effectively

- Construct complex searches appropriate to different digital and print resources

- Access full text information, both print and digital, read and download online material and data

- Use appropriate techniques to collect new data

- Keep up to date with new information

- Engage with their community to share information

- Identify when the information need has not been met

- Use online and printed help and can find personal, expert help

- The abilities connected with the Gather pillar overlap, in some aspects, with those in other chapters. Where this is the case, those abilities are not addressed in this chapter.

The following is a graphic representation of the bulleted list that describes the Gather Pillar:

- The difference between free and paid resources

- The risks involved in operating in a virtual world

- The importance of appraising and evaluating search result

Information and the Internet

Traditionally, information has been organized in different formats, usually as a result of the time it took to gather and publish the information. For example, the purpose of news reporting is to inform the public about the basic facts of an event. This information needs to be disseminated quickly, so it is published daily in print, online, on broadcast television, and radio media. More in-depth treatment of information takes longer to research, write, and publish and traditionally was published in scholarly journals and books.

Today, information is still published in traditional formats as well as in newly evolving formats on the Internet. These new information formats are loosely defined as Web 2.0 formats and can include electronic journals, books, news websites, blogs, Twitter, Facebook, and location postings. The coexistence of all of these information formats is messy and chaotic. The process for finding relevant information is not always clear.

One way to make some sense out of the current information universe is to thoroughly understand traditional information formats. We can then understand the concepts inherent in the information formats found online. There are some direct correlations such as books and journal articles, but there are also some newer formats like tweets that didn’t exist until recently.

Let’s look at the news industry. Many traditional newspapers are shutting down and those that remain are retrenching. While there are many reasons for this, one of the major trends has been the rise of the Internet. In the United States, more than 50 percent of the population reads the news online.

Indeed, online news sites provide a different and, some might argue, a more relevant experience for the reader. They offer video and sound, up-to-the-minute updates on breaking news, and the ability to interact with the content by posting comments. Another important feature of online news is that search engines can deliver content from the site in response to a query. In other words, readers don’t have to visit a site such as the New York Times in order to read its content.

This has both positive and negative consequences. The positive consequence is that readers can quickly and conveniently obtain information from a variety of sources on a topic or event. The negative consequence is that it is more difficult to evaluate the credibility of the sources. We'll be exploring evaluating sources more later in this unit.

For Harry and his group, all of this means they will have to research many different kinds of information resources in order to create an effective information command center.

Twitter and Blog Postings

Many of the group’s Google results are from Twitter feeds and blog postings. These did not provide a lot of information. After all, a tweet consists of only 280 characters. However, these resources did help Harry’s group by suggesting key people, cities, technologies, and other resources associated with Super Storm Sandy to research.

Often a blog posting will provide a link to a longer, more useful resource. The students’ review of blogs and tweets also provided an otherwise unthought-of insight. As Harry and his group were reviewing Twitter feeds posted during Super Storm Sandy, they noted that people were using Twitter to inform their friends and relatives about their whereabouts, their health, and the conditions of their surroundings. Since electricity was not available, most televisions and radios did not work, but mobile technologies like Twitter served as effective communication tools. Once Harry realized this, a Twitter feed was quickly incorporated into his command center’s communication plan.

Newspaper Articles

One of the members of Harry’s group suggested they should consult a newspaper to see what role the newspaper played to help the city understand the destruction caused by the storm. The group chose the New York Times. The New York Times can be accessed online and articles from the day of the storm can be viewed.

However, the group found that more useful information was published in the New York Times in the days after the storm. Harry’s initial search of the New York Times for articles containing the phrase super storm Sandy published on October 29, 2012 resulted in some blog postings from reporters and many stories about damage from the storm. But when Harry reentered his search without a date limit, he retrieved articles that analyzed how the region’s municipalities performed during the storm. It takes time to conduct this type of analysis, so looking for information that was published days, weeks, or months after the storm took place was a good strategy.

One limitation Harry encountered was a paywall on the New York Times website. He was able to access a few articles for free, but after viewing five articles, the website restricted access without a New York Times subscription. This is where library databases can become extremely valuable. Your college will subscribe to databases that give you access to important newspaper content, including the New York Times, which is included in the US Major Dailies and Opposing Viewpoints databases.

Primary Sources

Another member of Harry’s group recalled that he had cousins in New York City who experienced Super Storm Sandy firsthand. He offered to interview his cousins about their experiences during the storm. This type of information is known as a primary information or source. Primary sources are accounts from a person or persons who have firsthand knowledge of an event. Speeches, photographs, diaries, autobiographies, and interviews are all primary sources.

In this case, the primary source is still alive and is accessible to Harry’s group. However, some researchers are not so fortunate. If this is the case, primary sources can still be found in a variety of locations and formats. There are many online sites that have created digitized collections of copies of diaries and letters from historical events. It is important to remember that primary sources are not limited to a single format. You may find them in books, journals, newspapers, email, websites, and artwork.

The CRC Library has a guide to source types (bookmark this page - it will remain published even after you finish this course) that can help you differentiate the kind of source you're using.

Scholarly Articles

The results of the research that Harry and his group has done are useful, but Harry is concerned that there might be too much focus on Super Storm Sandy. He wants to find more information on crisis and disaster management in general. Harry thinks that there might be general standards or practices that should be incorporated into his group’s plan. Journal articles and books might provide this information.

Harry starts his search for journal articles by using a multidisciplinary database because he is not sure which specific disciplines will cover the information he seeks. He constructs and executes a search query and finds that the abstracts included in the results help him choose several peer-reviewed, or scholarly, articles to read.

Scholarly journal articles usually include an abstract at the beginning of the article. An abstract summarizes the contents of the article. In an abstract, key points as well as conclusions are briefly described. Abstracts are often included in the database record.

Researchers find this information helpful when deciding whether or not to retrieve the whole article.

Most of the articles that Harry chooses are available in PDF format from the database, but there are a few articles that look very relevant that don’t have links to a PDF. Harry really wants to read these articles so he decides to try to find out if there is another way to obtain the full text. He consults a librarian who instructs him to look for the title of the journal (not the article) in the online catalog. The catalog record will provide information on whether the journal is available online from another database.

Journals, and the articles they contain, are often quite expensive. Libraries spend a large part of their collection budget subscribing to journals in both print and online formats. You may have noticed that a Google Scholar search will provide the citation to a journal article but will not link to the full text. This happens because Google does not subscribe to journals. It only searches and retrieves freely available web content.

However, libraries do subscribe to journals and have entered into agreements to share their journal and book collections with other libraries. If you are affiliated with a library as a student, staff, or faculty member, you have access to many other libraries’ resources, through a service called interlibrary loan. Do not pay the large sums required to purchase access to articles unless you do not have another way to obtain the material, and you are unable to find a substitute resource that provides the information you need.

There is one more feature Harry found while searching in databases: some offer the option of an alert service. This feature allows Harry to enter the most productive search strings, as well as his email address. When new items are added to the database that fit his search, he receives an alert. Harry found this to be a great way to keep up to date with new articles on his topic without having to initiate a new search.

Books

Next, Harry’s group looks for books on the topic. They search the library’s online catalog using search terms that were successful in their database searches. They find some great titles and head to the library book cases to retrieve them.

Most academic libraries use the Library of Congress classification system to organize their books and other resources. The Library of Congress classification systems divides a library’s collection into 21 classes or categories. A specific letter of the alphabet is assigned to each class. More detailed divisions are accomplished with two and three letter combinations. Book shelves in most academic libraries are marked with a Library of Congress letter-number combination to correspond to the Library of Congress

letter-number combination on the spines of library materials. This is often referred to as a call number and it is noted in the catalog record of every physical item on the library shelves.

Harry uses the call numbers to locate some books that he found in the catalog. He is happily surprised to find that there are also some really useful books sitting on the shelf right next to the books he previously identified. This is a handy way to find additional information resources on a topic. It is more efficient to first search the online catalog to locate relevant resources and then search the shelves.

Conclusions

Harry and his classmates have spent time gathering information to help them create a realistic and accurate crisis command center. They accessed and used Web 2.0 information sources in the form of Twitter feeds and blogs. They used online newspapers and the library's online databases to find journal articles. They even gathered some very useful hard copy books.

During this process, the students learned about different ways that information is organized including the Library of Congress classification system. Harry was amazed at the wealth of quality information he was able to gather. It took him a while and the process was more complicated than just searching the web, but Harry now feels more confident about acing the assignment. He also feels that he learned more than how to set up a command center. He learned how to engage in academic research!

This chapter compiled, reworked, and/or written by Andi Adkins Pogue and is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Original sources used to create content (also licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0):

Gather: Finding what you need. (2016). In G. Bobish & T. Jacobson (Eds.), The information literacy user's guide. Milne Publishing. https://milnepublishing.geneseo.edu/the-information-literacy-users-guide-an-open-online-textbook/chapter/gather-finding-what-you-need/

Plan: Developing research strategies. (2016). In G. Bobish & T. Jacobson (Eds.), The information literacy user's guide. Milne Publishing. https://milnepublishing.geneseo.edu/the-information-literacy-users-guide-an-open-online-textbook/chapter/plan-developing-research-strategies/

Scope: Knowing what is available. (2016). In G. Bobish & T. Jacobson (Eds.), The information literacy user's guide. Milne Publishing.