3.8: D.H. Lawrence (1885-1930)

- Page ID

- 41798

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)David Herbert Lawrence was born in Eastwood, Nottinghamshire, where his father Arthur John Lawrence labored as a coal miner. His mother Lydia Lawrence, a well-educated and literary woman from a middle-class family, inspired Lawrence’s interest in literature. She also highlighted his lifelong conflict with the labor industry and class system in England. His father’s work in the coal mine, from which daily he would almost symbolically emerge blackened by the coal, helped inspire Lawrence’s interest in essential, core identity and the unconscious.

Despite almost chronic illness and being at odds with his environment, Lawrence earned a scholarship to the Nottingham High School. After graduating, he worked at the  British School in Eastwood, where he met Jessie Chambers who encouraged his intellectual and literary pursuits, especially his writing. In 1908, he obtained a teaching certificate from the University College of Nottingham then went on to teach at an Elementary school in London.

British School in Eastwood, where he met Jessie Chambers who encouraged his intellectual and literary pursuits, especially his writing. In 1908, he obtained a teaching certificate from the University College of Nottingham then went on to teach at an Elementary school in London.

Jessie Chambers sent three of Lawrence’s poems to Ford Madox Hueffer (later Ford Madox Ford) (1873-1939), editor of The English Review. He published them and saw to Lawrence’s introduction to the London literary scene. Upon Hueffer’s recommendation of Lawrence’s short story “Odour of Chrysanthemums,” William Heinemann published Lawrence’s first novel, The White Peacock (1910). Autobiographical like much of Lawrence’s work, The White Peacock depicts his relationship with Jessie Chambers, who also appeared as Miriam in his Sons and Lovers (1913).

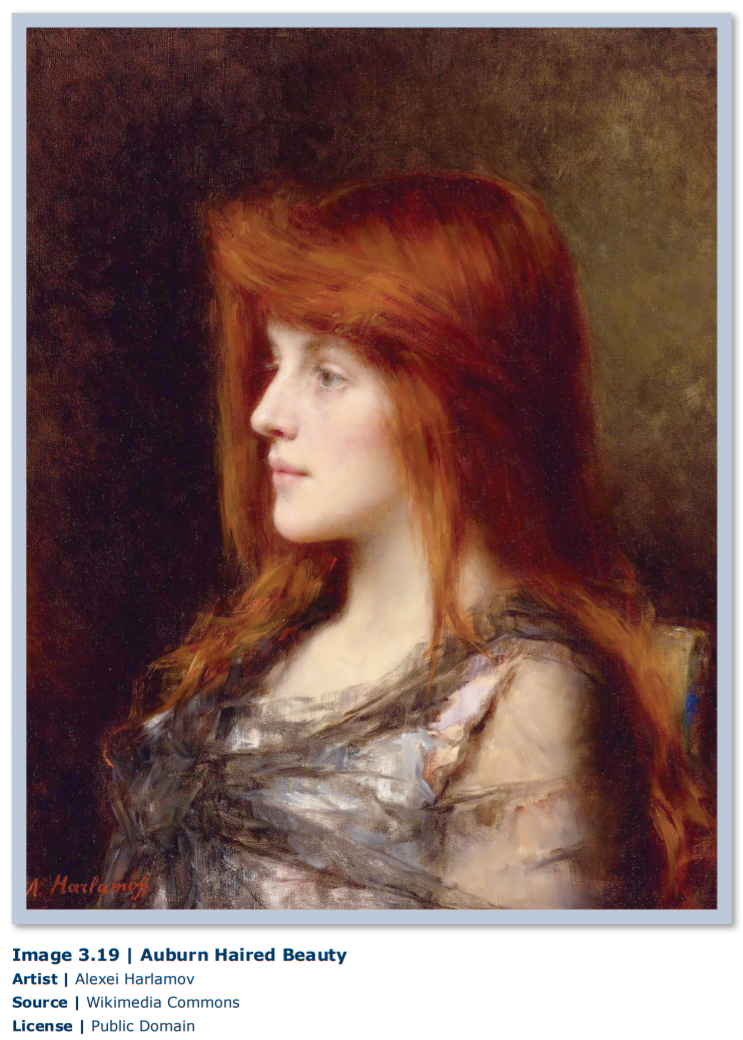

The mother in Sons and Lovers is closely based upon Lydia Lawrence who grew to disdain what she viewed as her husband’s coarseness and brutality and who transferred her affection, to an overwhelming degree, to her sons. Marital unhappiness recurs in The Rainbow (1915), whose Tom Brangwen marries the non-British Lydia Lensky. Lawrence himself, after having been engaged to childhood friend Louie Burrows, fell in love with Frieda von Richthofen Weekley (1879-1956), distant cousin of Manfred von Richthofen (aka The Red Baron), wife of Lawrence’s Nottingham College German tutor, and mother of three children. Her reciprocal passion for Lawrence led the two to elope to the Continent. In 1914 after her divorce, she and Lawrence returned to England and married.

Lawrence’s growing discontent with western civilization, particularly England, was exacerbated by the harassment he and his wife received during England’s war with Germany in WWI, at the end of which he and Frieda left England for the remainder of Lawrence’s life (they returned twice only briefly). Also hindering was the censorship of his novels, beginning with The Rainbow. The sexual explicitness of Lawrence’s novels, an explicitness culminating most notoriously in Lady Chatterly’s Lover (1928), elucidates Lawrence’s evolving mythos that he articulates in Psychoanalysis and the Unconscious (1922) and Fantasia of the Unconscious (1922) and later in his pagan/Druid poems. Lawrence criticized what he saw as the errors of modern civilization, to the point of harboring apocalyptic visions with a smash up of the human world to make way for better, more expressive species.

Like T. S. Eliot, Lawrence deplored the tendency of modern human beings to put their energies into their heads, to experience their sexuality vicariously rather than directly. He advocated instead connections, of the reason and the unconscious, mind and body, man and woman, human and nature, sky and earth. He thought the individual needed personal integrity and inter-relatedness, needed to balance forces of attraction and repulsion, sympathy and volition both within themselves and with the world around them. For Lawrence, relationships of man and woman (as well as humans with nature and vice versa) helped to realize the individual’s core identity in the face of industrialization and institutionalized religion, helped individuals get outside of themselves to the vital, quick forces of humankind and life itself.

Lawrence continued to philosophize and mythologize in his writing until he died of tuberculosis at the age of forty-four.

3.8.1: “The Odour of Chrysanthemums”

I

The small locomotive engine, Number 4, came clanking, stumbling down from Selston—with seven full waggons. It appeared round the corner with loud threats of speed, but the colt that it startled from among the gorse, which still flickered indistinctly in the raw afternoon, outdistanced it at a canter. A woman, walking up the railway line to Underwood, drew back into the hedge, held her basket aside, and watched the footplate of the engine advancing. The trucks thumped heavily past, one by one, with slow inevitable movement, as she stood insignificantly trapped between the jolting black waggons and the hedge; then they curved away towards the coppice where the withered oak leaves dropped noiselessly, while the birds, pulling at the scarlet hips beside the track, made off into the dusk that had already crept into the spinney. In the open, the smoke from the engine sank and cleaved to the rough grass. The fields were dreary and forsaken, and in the marshy strip that led to the whimsey, a reedy pit-pond, the fowls had already abandoned their run among the alders, to roost in the tarred fowl-house. The pit-bank loomed up beyond the pond, flames like red sores licking its ashy sides, in the afternoon’s stagnant light. Just beyond rose the tapering chimneys and the clumsy black head-stocks of Brinsley Colliery. The two wheels were spinning fast up against the sky, and the winding-engine rapped out its little spasms. The miners were being turned up.

The engine whistled as it came into the wide bay of railway lines beside the colliery, where rows of trucks stood in harbour.

Miners, single, trailing and in groups, passed like shadows diverging home. At the edge of the ribbed level of sidings squat a low cottage, three steps down from the cinder track. A large bony vine clutched at the house, as if to claw down the tiled roof. Round the bricked yard grew a few wintry primroses. Beyond, the long garden sloped down to a bush-covered brook course. There were some twiggy apple trees, winter-crack trees, and ragged cabbages. Beside the path hung dishevelled pink chrysanthemums, like pink cloths hung on bushes. A woman came stooping out of the felt-covered fowl-house, half-way down the garden. She closed and padlocked the door, then drew herself erect, having brushed some bits from her white apron.

She was a tall woman of imperious mien, handsome, with definite black eyebrows. Her smooth black hair was parted exactly. For a few moments she stood steadily watching the miners as they passed along the railway: then she turned towards the brook course. Her face was calm and set, her mouth was closed with disillusionment. After a moment she called:

“John!” There was no answer. She waited, and then said distinctly:

“Where are you?”

“Here!” replied a child’s sulky voice from among the bushes. The woman looked piercingly through the dusk.

“Are you at that brook?” she asked sternly.

For answer the child showed himself before the raspberry-canes that rose like whips. He was a small, sturdy boy of five. He stood quite still, defiantly.

“Oh!” said the mother, conciliated.

“I thought you were down at that wet brook—and you remember what I told you —” The boy did not move or answer.

“Come, come on in,” she said more gently, “it’s getting dark. There’s your grandfather’s engine coming down the line!”

The lad advanced slowly, with resentful, taciturn movement. He was dressed in trousers and waistcoat of cloth that was too thick and hard for the size of the garments. They were evidently cut down from a man’s clothes.

As they went slowly towards the house he tore at the ragged wisps of chrysanthemums and dropped the petals in handfuls along the path.

“Don’t do that—it does look nasty,” said his mother. He refrained, and she, suddenly pitiful, broke off a twig with three or four wan flowers and held them against her face. When mother and son reached the yard her hand hesitated, and instead of laying the flower aside, she pushed it in her apron-band. The mother and son stood at the foot of the three steps looking across the bay of lines at the passing home of the miners. The trundle of the small train was imminent. Suddenly the engine loomed past the house and came to a stop opposite the gate.

The engine-driver, a short man with round grey beard, leaned out of the cab high above the woman.

“Have you got a cup of tea?” he said in a cheery, hearty fashion.

It was her father. She went in, saying she would mash. Directly, she returned.

“I didn’t come to see you on Sunday,” began the little grey-bearded man.

“I didn’t expect you,” said his daughter.

The engine-driver winced; then, reassuming his cheery, airy manner, he said:

“Oh, have you heard then? Well, and what do you think —?”

“I think it is soon enough,” she replied.

At her brief censure the little man made an impatient gesture, and said coaxingly, yet with dangerous coldness:

“Well, what’s a man to do? It’s no sort of life for a man of my years, to sit at my own hearth like a stranger. And if I’m going to marry again it may as well be soon as late—what does it matter to anybody?”

The woman did not reply, but turned and went into the house. The man in the engine-cab stood assertive, till she returned with a cup of tea and a piece of bread and butter on a plate. She went up the steps and stood near the footplate of the hissing engine.

“You needn’t ‘a’ brought me bread an’ butter,” said her father. “But a cup of tea”— he sipped appreciatively —“it’s very nice.” He sipped for a moment or two, then: “I hear as Walter’s got another bout on,” he said.

“When hasn’t he?” said the woman bitterly.

“I heered tell of him in the ‘Lord Nelson’ braggin’ as he was going to spend that b —— afore he went: half a sovereign that was.”

“When?” asked the woman.

“A’ Sat’day night—I know that’s true.”

“Very likely,” she laughed bitterly. “He gives me twenty-three shillings.”

“Aye, it’s a nice thing, when a man can do nothing with his money but make a beast of himself!” said the grey-whiskered man. The woman turned her head away. Her father swallowed the last of his tea and handed her the cup.

“Aye,” he sighed, wiping his mouth.

“It’s a settler, it is —”

He put his hand on the lever. The little engine strained and groaned, and the train rumbled towards the crossing. The woman again looked across the metals. Darkness was settling over the spaces of the railway and trucks: the miners, in grey sombre groups, were still passing home. The winding-engine pulsed hurriedly, with brief pauses. Elizabeth Bates looked at the dreary flow of men, then she went indoors. Her husband did not come.

The kitchen was small and full of firelight; red coals piled glowing up the chimney mouth. All the life of the room seemed in the white, warm hearth and the steel fender reflecting the red fire. The cloth was laid for tea; cups glinted in the shadows. At the back, where the lowest stairs protruded into the room, the boy sat struggling with a knife and a piece of whitewood. He was almost hidden in the shadow. It was half-past four. They had but to await the father’s coming to begin tea. As the mother watched her son’s sullen little struggle with the wood, she saw herself in his silence and pertinacity; she saw the father in her child’s indifference to all but himself. She seemed to be occupied by her husband. He had probably gone past his home, slunk past his own door, to drink before he came in, while his dinner spoiled and wasted in waiting. She glanced at the clock, then took the potatoes to strain them in the yard. The garden and fields beyond the brook were closed in uncertain darkness. When she rose with the saucepan, leaving the drain steaming into the night behind her, she saw the yellow lamps were lit along the high road that went up the hill away beyond the space of the railway lines and the field.

Then again she watched the men trooping home, fewer now and fewer.

Indoors the fire was sinking and the room was dark red. The woman put her saucepan on the hob, and set a batter pudding near the mouth of the oven. Then she stood unmoving. Directly, gratefully, came quick young steps to the door. Someone hung on the latch a moment, then a little girl entered and began pulling off her outdoor things, dragging a mass of curls, just ripening from gold to brown, over her eyes with her hat.

Her mother chid her for coming late from school, and said she would have to keep her at home the dark winter days.

“Why, mother, it’s hardly a bit dark yet. The lamp’s not lighted, and my father’s not home.”

“No, he isn’t. But it’s a quarter to five! Did you see anything of him?”

The child became serious. She looked at her mother with large, wistful blue eyes.

“No, mother, I’ve never seen him. Why? Has he come up an’ gone past, to Old Brinsley? He hasn’t, mother, ‘cos I never saw him.”

“He’d watch that,” said the mother bitterly, “he’d take care as you didn’t see him. But you may depend upon it, he’s seated in the ‘Prince o’ Wales’. He wouldn’t be this late.”

The girl looked at her mother piteously.

“Let’s have our teas, mother, should we?” said she.

The mother called John to table. She opened the door once more and looked out across the darkness of the lines. All was deserted: she could not hear the windingengines.

“Perhaps,” she said to herself, “he’s stopped to get some ripping done.”

They sat down to tea. John, at the end of the table near the door, was almost lost in the darkness. Their faces were hidden from each other. The girl crouched against the fender slowly moving a thick piece of bread before the fire. The lad, his face a dusky mark on the shadow, sat watching her who was transfigured in the red glow.

“I do think it’s beautiful to look in the fire,” said the child.

“Do you?” said her mother. “Why?”

“It’s so red, and full of little caves—and it feels so nice, and you can fair smell it.”

“It’ll want mending directly,” replied her mother, “and then if your father comes he’ll carry on and say there never is a fire when a man comes home sweating from the pit.—A public-house is always warm enough.”

There was silence till the boy said complainingly: “Make haste, our Annie.”

“Well, I am doing! I can’t make the fire do it no faster, can I?”

“She keeps wafflin’ it about so’s to make ‘er slow,” grumbled the boy.

“Don’t have such an evil imagination, child,” replied the mother.

Soon the room was busy in the darkness with the crisp sound of crunching. The mother ate very little. She drank her tea determinedly, and sat thinking. When she rose her anger was evident in the stern unbending of her head. She looked at the pudding in the fender, and broke out:

“It is a scandalous thing as a man can’t even come home to his dinner! If it’s crozzled up to a cinder I don’t see why I should care. Past his very door he goes to get to a public-house, and here I sit with his dinner waiting for him —”

She went out. As she dropped piece after piece of coal on the red fire, the shadows fell on the walls, till the room was almost in total darkness.

“I canna see,” grumbled the invisible John. In spite of herself, the mother laughed.

“You know the way to your mouth,” she said. She set the dustpan outside the door. When she came again like a shadow on the hearth, the lad repeated, complaining sulkily:

“I canna see.”

“Good gracious!” cried the mother irritably, “you’re as bad as your father if it’s a bit dusk!”

Nevertheless she took a paper spill from a sheaf on the mantelpiece and proceeded to light the lamp that hung from the ceiling in the middle of the room. As she reached up, her figure displayed itself just rounding with maternity.

“Oh, mother —!” exclaimed the girl.

“What?” said the woman, suspended in the act of putting the lamp glass over the flame. The copper reflector shone handsomely on her, as she stood with uplifted arm, turning to face her daughter.

“You’ve got a flower in your apron!” said the child, in a little rapture at this unusual event.

“Goodness me!” exclaimed the woman, relieved. “One would think the house was afire.” She replaced the glass and waited a moment before turning up the wick. A pale shadow was seen floating vaguely on the floor.

“Let me smell!” said the child, still rapturously, coming forward and putting her face to her mother’s waist.

“Go along, silly!” said the mother, turning up the lamp. The light revealed their suspense so that the woman felt it almost unbearable. Annie was still bending at her waist. Irritably, the mother took the flowers out from her apron-band.

“Oh, mother—don’t take them out!” Annie cried, catching her hand and trying to replace the sprig.

“Such nonsense!” said the mother, turning away. The child put the pale chrysanthemums to her lips, murmuring:

“Don’t they smell beautiful!”

Her mother gave a short laugh.

“No,” she said, “not to me. It was chrysanthemums when I married him, and chrysanthemums when you were born, and the first time they ever brought him home drunk, he’d got brown chrysanthemums in his button-hole.”She looked at the children. Their eyes and their parted lips were wondering. The mother sat rocking in silence for some time. Then she looked at the clock.

“Twenty minutes to six!” In a tone of fine bitter carelessness she continued: “Eh, he’ll not come now till they bring him. There he’ll stick! But he needn’t come rolling in here in his pit-dirt, for I won’t wash him. He can lie on the floor—Eh, what a fool I’ve been, what a fool! And this is what I came here for, to this dirty hole, rats and all, for him to slink past his very door. Twice last week—he’s begun now—”

She silenced herself, and rose to clear the table.

While for an hour or more the children played, subduedly intent, fertile of imagination, united in fear of the mother’s wrath, and in dread of their father’s home-coming, Mrs Bates sat in her rocking-chair making a ‘singlet’ of thick creamcoloured flannel, which gave a dull wounded sound as she tore off the grey edge. She worked at her sewing with energy, listening to the children, and her anger wearied itself, lay down to rest, opening its eyes from time to time and steadily watching, its ears raised to listen. Sometimes even her anger quailed and shrank, and the mother suspended her sewing, tracing the footsteps that thudded along the sleepers outside; she would lift her head sharply to bid the children ‘hush’, but she recovered herself in time, and the footsteps went past the gate, and the children were not flung out of their playing world.

But at last Annie sighed, and gave in. She glanced at her waggon of slippers, and loathed the game. She turned plaintively to her mother.

“Mother!”— but she was inarticulate.

John crept out like a frog from under the sofa. His mother glanced up.

“Yes,” she said, “just look at those shirt-sleeves!”

The boy held them out to survey them, saying nothing. Then somebody called in a hoarse voice away down the line, and suspense bristled in the room, till two people had gone by outside, talking.

“It is time for bed,” said the mother.

“My father hasn’t come,” wailed Annie plaintively. But her mother was primed with courage.

“Never mind. They’ll bring him when he does come—like a log.” She meant there would be no scene. “And he may sleep on the floor till he wakes himself. I know he’ll not go to work tomorrow after this!”

The children had their hands and faces wiped with a flannel. They were very quiet. When they had put on their nightdresses, they said their prayers, the boy mumbling. The mother looked down at them, at the brown silken bush of intertwining curls in the nape of the girl’s neck, at the little black head of the lad, and her heart burst with anger at their father who caused all three such distress. The children hid their faces in her skirts for comfort.

When Mrs Bates came down, the room was strangely empty, with a tension of expectancy. She took up her sewing and stitched for some time without raising her head. Meantime her anger was tinged with fear.

II

The clock struck eight and she rose suddenly, dropping her sewing on her chair. She went to the stairfoot door, opened it, listening. Then she went out, locking the door behind her.

Something scuffled in the yard, and she started, though she knew it was only the rats with which the place was overrun. The night was very dark. In the great bay of railway lines, bulked with trucks, there was no trace of light, only away back she could see a few yellow lamps at the pit-top, and the red smear of the burning pit-bank on the night. She hurried along the edge of the track, then, crossing the converging lines, came to the stile by the white gates, whence she emerged on the road. Then the fear which had led her shrank. People were walking up to New Brinsley; she saw the lights in the houses; twenty yards further on were the broad windows of the ‘Prince of Wales’, very warm and bright, and the loud voices of men could be heard distinctly. What a fool she had been to imagine that anything had happened to him! He was merely drinking over there at the ‘Prince of Wales’. She faltered. She had never yet been to fetch him, and she never would go. So she continued her walk towards the long straggling line of houses, standing blank on the highway. She entered a passage between the dwellings.

“Mr Rigley?—Yes! Did you want him? No, he’s not in at this minute.”

The raw-boned woman leaned forward from her dark scullery and peered at the other, upon whom fell a dim light through the blind of the kitchen window.

“Is it Mrs Bates?” she asked in a tone tinged with respect.

“Yes. I wondered if your Master was at home. Mine hasn’t come yet.”

“‘Asn’t ‘e! Oh, Jack’s been ‘ome an ‘ad ‘is dinner an’ gone out. E’s just gone for ‘alf an hour afore bedtime. Did you call at the ‘Prince of Wales’?”“No —”

“No, you didn’t like —! It’s not very nice.” The other woman was indulgent. There was an awkward pause. “Jack never said nothink about—about your Mester,” she said.

“No!—I expect he’s stuck in there!”

Elizabeth Bates said this bitterly, and with recklessness. She knew that the woman across the yard was standing at her door listening, but she did not care. As she turned:

“Stop a minute! I’ll just go an’ ask Jack if e’ knows anythink,” said Mrs Rigley.

“Oh, no—I wouldn’t like to put —!”

“Yes, I will, if you’ll just step inside an’ see as th’ childer doesn’t come downstairs and set theirselves afire.”

Elizabeth Bates, murmuring a remonstrance, stepped inside. The other woman apologized for the state of the room.

The kitchen needed apology. There were little frocks and trousers and childish undergarments on the squab and on the floor, and a litter of playthings everywhere. On the black American cloth of the table were pieces of bread and cake, crusts, slops, and a teapot with cold tea.

“Eh, ours is just as bad,” said Elizabeth Bates, looking at the woman, not at the house.

Mrs Rigley put a shawl over her head and hurried out, saying:

“I shanna be a minute.”

The other sat, noting with faint disapproval the general untidiness of the room. Then she fell to counting the shoes of various sizes scattered over the floor. There were twelve. She sighed and said to herself, “No wonder!”— glancing at the litter. There came the scratching of two pairs of feet on the yard, and the Rigleys entered. Elizabeth Bates rose. Rigley was a big man, with very large bones. His head looked particularly bony. Across his temple was a blue scar, caused by a wound got in the pit, a wound in which the coal-dust remained blue like tattooing.

“Asna ‘e come whoam yit?” asked the man, without any form of greeting, but with deference and sympathy. “I couldna say wheer he is —‘e’s non ower theer!”— he jerked his head to signify the ‘Prince of Wales’.

“‘E’s ‘appen gone up to th’ ‘Yew’,” said Mrs Rigley.

There was another pause. Rigley had evidently something to get off his mind:

“Ah left ’im finishin’ a stint,” he began. “Loose-all ‘ad bin gone about ten minutes when we com’n away, an’ I shouted, ‘Are ter comin’, Walt?’ an’ ‘e said, ‘Go on, Ah shanna be but a’ef a minnit,’ so we com’n ter th’ bottom, me an’ Bowers, thinkin’ as ‘e wor just behint, an’ ‘ud come up i’ th’ next bantle —”

He stood perplexed, as if answering a charge of deserting his mate. Elizabeth Bates, now again certain of disaster, hastened to reassure him:

“I expect ‘e’s gone up to th’ ‘Yew Tree’, as you say. It’s not the first time. I’ve fretted myself into a fever before now. He’ll come home when they carry him.”

“Ay, isn’t it too bad!” deplored the other woman.

“I’ll just step up to Dick’s an’ see if ‘e IS theer,” offered the man, afraid of appearing alarmed, afraid of taking liberties.

“Oh, I wouldn’t think of bothering you that far,” said Elizabeth Bates, with emphasis, but he knew she was glad of his offer.

As they stumbled up the entry, Elizabeth Bates heard Rigley’s wife run across the yard and open her neighbour’s door. At this, suddenly all the blood in her body seemed to switch away from her heart.

“Mind!” warned Rigley. “Ah’ve said many a time as Ah’d fill up them ruts in this entry, sumb’dy ‘ll be breakin’ their legs yit.”

She recovered herself and walked quickly along with the miner.

“I don’t like leaving the children in bed, and nobody in the house,” she said.

“No, you dunna!” he replied courteously. They were soon at the gate of the cottage.

“Well, I shanna be many minnits. Dunna you be frettin’ now, ‘e’ll be all right,” said the butty.

“Thank you very much, Mr Rigley,” she replied.

“You’re welcome!” he stammered, moving away. “I shanna be many minnits.”

The house was quiet. Elizabeth Bates took off her hat and shawl, and rolled back the rug. When she had finished, she sat down. It was a few minutes past nine. She was startled by the rapid chuff of the winding-engine at the pit, and the sharp whirr of the brakes on the rope as it descended. Again she felt the painful sweep of her blood, and she put her hand to her side, saying aloud, “Good gracious!—it’s only the nine o’clock deputy going down,” rebuking herself.

She sat still, listening. Half an hour of this, and she was wearied out.

“What am I working myself up like this for?” she said pitiably to herself, “I s’ll only be doing myself some damage.”

She took out her sewing again.

At a quarter to ten there were footsteps. One person! She watched for the door to open. It was an elderly woman, in a black bonnet and a black woollen shawl— his mother. She was about sixty years old, pale, with blue eyes, and her face all wrinkled and lamentable. She shut the door and turned to her daughter-in-law peevishly.

“Eh, Lizzie, whatever shall we do, whatever shall we do!” she cried.

Elizabeth drew back a little, sharply.

“What is it, mother?” she said.

The elder woman seated herself on the sofa.

“I don’t know, child, I can’t tell you!”— she shook her head slowly. Elizabeth sat watching her, anxious and vexed.

“I don’t know,” replied the grandmother, sighing very deeply. “There’s no end to my troubles, there isn’t. The things I’ve gone through, I’m sure it’s enough —!” She wept without wiping her eyes, the tears running.

“But, mother,” interrupted Elizabeth, “what do you mean? What is it?”

The grandmother slowly wiped her eyes. The fountains of her tears were stopped by Elizabeth’s directness. She wiped her eyes slowly.

“Poor child! Eh, you poor thing!” she moaned. “I don’t know what we’re going to do, I don’t—and you as you are—it’s a thing, it is indeed!”

Elizabeth waited.

“Is he dead?” she asked, and at the words her heart swung violently, though she felt a slight flush of shame at the ultimate extravagance of the question. Her words sufficiently frightened the old lady, almost brought her to herself.

“Don’t say so, Elizabeth! We’ll hope it’s not as bad as that; no, may the Lord spare us that, Elizabeth. Jack Rigley came just as I was sittin’ down to a glass afore going to bed, an’ ‘e said, ‘‘Appen you’ll go down th’ line, Mrs Bates. Walt’s had an accident. ‘Appen you’ll go an’ sit wi’ ‘er till we can get him home.’ I hadn’t time to ask him a word afore he was gone. An’ I put my bonnet on an’ come straight down, Lizzie. I thought to myself, ‘Eh, that poor blessed child, if anybody should come an’ tell her of a sudden, there’s no knowin’ what’ll ‘appen to ‘er.’ You mustn’t let it upset you, Lizzie—or you know what to expect. How long is it, six months—or is it five, Lizzie? Ay!”— the old woman shook her head —“time slips on, it slips on! Ay!”

Elizabeth’s thoughts were busy elsewhere. If he was killed—would she be able to manage on the little pension and what she could earn?—she counted up rapidly. If he was hurt—they wouldn’t take him to the hospital—how tiresome he would be to nurse!—but perhaps she’d be able to get him away from the drink and his hateful ways. She would—while he was ill. The tears offered to come to her eyes at the picture. But what sentimental luxury was this she was beginning?—She turned to consider the children. At any rate she was absolutely necessary for them. They were her business.

“Ay!” repeated the old woman, “it seems but a week or two since he brought me his first wages. Ay—he was a good lad, Elizabeth, he was, in his way. I don’t know why he got to be such a trouble, I don’t. He was a happy lad at home, only full of spirits. But there’s no mistake he’s been a handful of trouble, he has! I hope the Lord’ll spare him to mend his ways. I hope so, I hope so. You’ve had a sight o’ trouble with him, Elizabeth, you have indeed. But he was a jolly enough lad wi’ me, he was, I can assure you. I don’t know how it is . . .”

The old woman continued to muse aloud, a monotonous irritating sound, while Elizabeth thought concentratedly, startled once, when she heard the windingengine chuff quickly, and the brakes skirr with a shriek. Then she heard the engine more slowly, and the brakes made no sound. The old woman did not notice. Elizabeth waited in suspense.

The mother-in-law talked, with lapses into silence.

“But he wasn’t your son, Lizzie, an’ it makes a difference. Whatever he was, I remember him when he was little, an’ I learned to understand him and to make allowances. You’ve got to make allowances for them —”

It was half-past ten, and the old woman was saying: “But it’s trouble from beginning to end; you’re never too old for trouble, never too old for that —” when the gate banged back, and there were heavy feet on the steps.

“I’ll go, Lizzie, let me go,” cried the old woman, rising. But Elizabeth was at the door. It was a man in pit-clothes.

“They’re bringin’ ’im, Missis,” he said. Elizabeth’s heart halted a moment. Then it surged on again, almost suffocating her.

“Is he—is it bad?” she asked. The man turned away, looking at the darkness:

“The doctor says ‘e’d been dead hours. ‘E saw ’im i’ th’ lamp-cabin.”

The old woman, who stood just behind Elizabeth, dropped into a chair, and folded her hands, crying: “Oh, my boy, my boy!”

“Hush!” said Elizabeth, with a sharp twitch of a frown. “Be still, mother, don’t waken th’ children: I wouldn’t have them down for anything!”

The old woman moaned softly, rocking herself. The man was drawing away. Elizabeth took a step forward.

“How was it?” she asked.

“Well, I couldn’t say for sure,” the man replied, very ill at ease. “‘E wor finishin’ a stint an’ th’ butties ‘ad gone, an’ a lot o’ stuff come down atop ‘n ’im.”

“And crushed him?” cried the widow, with a shudder.

“No,” said the man, “it fell at th’ back of ’im. ‘E wor under th’ face, an’ it niver touched ’im. It shut ’im in. It seems ‘e wor smothered.”

Elizabeth shrank back. She heard the old woman behind her cry:

“What?—what did ‘e say it was?”

The man replied, more loudly: “‘E wor smothered!”

Then the old woman wailed aloud, and this relieved Elizabeth.

“Oh, mother,” she said, putting her hand on the old woman, “don’t waken th’ children, don’t waken th’ children.”

She wept a little, unknowing, while the old mother rocked herself and moaned. Elizabeth remembered that they were bringing him home, and she must be ready. “They’ll lay him in the parlour,” she said to herself, standing a moment pale and perplexed.

Then she lighted a candle and went into the tiny room. The air was cold and damp, but she could not make a fire, there was no fireplace. She set down the candle and looked round. The candle-light glittered on the lustre-glasses, on the two vases that held some of the pink chrysanthemums, and on the dark mahogany. There was a cold, deathly smell of chrysanthemums in the room. Elizabeth stood looking at the flowers. She turned away, and calculated whether there would be room to lay him on the floor, between the couch and the chiffonier. She pushed the chairs aside. There would be room to lay him down and to step round him. Then she fetched the old red tablecloth, and another old cloth, spreading them down to save her bit of carpet. She shivered on leaving the parlour; so, from the dresserdrawer she took a clean shirt and put it at the fire to air. All the time her motherin-law was rocking herself in the chair and moaning.

“You’ll have to move from there, mother,” said Elizabeth. “They’ll be bringing him in.

Come in the rocker.”

The old mother rose mechanically, and seated herself by the fire, continuing to lament. Elizabeth went into the pantry for another candle, and there, in the little penthouse under the naked tiles, she heard them coming. She stood still in the pantry doorway, listening. She heard them pass the end of the house, and come awkwardly down the three steps, a jumble of shuffling footsteps and muttering voices. The old woman was silent. The men were in the yard.

Then Elizabeth heard Matthews, the manager of the pit, say: “You go in first, Jim. Mind!”

The door came open, and the two women saw a collier backing into the room, holding one end of a stretcher, on which they could see the nailed pit-boots of the dead man. The two carriers halted, the man at the head stooping to the lintel of the door.

“Wheer will you have him?” asked the manager, a short, white-bearded man.

Elizabeth roused herself and came from the pantry carrying the unlighted candle.

“In the parlour,” she said.

“In there, Jim!” pointed the manager, and the carriers backed round into the tiny room.

The coat with which they had covered the body fell off as they awkwardly turned through the two doorways, and the women saw their man, naked to the waist, lying stripped for work. The old woman began to moan in a low voice of horror.

“Lay th’ stretcher at th’ side,” snapped the manager, “an’ put ’im on th’ cloths. Mind now, mind! Look you now —!”

One of the men had knocked off a vase of chrysanthemums. He stared awkwardly, then they set down the stretcher. Elizabeth did not look at her husband. As soon as she could get in the room, she went and picked up the broken vase and the flowers.

“Wait a minute!” she said.

The three men waited in silence while she mopped up the water with a duster.

“Eh, what a job, what a job, to be sure!” the manager was saying, rubbing his brow with trouble and perplexity. “Never knew such a thing in my life, never! He’d no business to ha’ been left. I never knew such a thing in my life! Fell over him clean as a whistle, an’ shut him in. Not four foot of space, there wasn’t—yet it scarce bruised him.”

He looked down at the dead man, lying prone, half naked, all grimed with coaldust.

“’‘Sphyxiated,’ the doctor said. It IS the most terrible job I’ve ever known. Seems as if it was done o’ purpose. Clean over him, an’ shut ’im in, like a mousetrap”— he made a sharp, descending gesture with his hand.

The colliers standing by jerked aside their heads in hopeless comment.

The horror of the thing bristled upon them all.

Then they heard the girl’s voice upstairs calling shrilly: “Mother, mother—who is it? Mother, who is it?”

Elizabeth hurried to the foot of the stairs and opened the door:

“Go to sleep!” she commanded sharply. “What are you shouting about? Go to sleep at once—there’s nothing —”

Then she began to mount the stairs. They could hear her on the boards, and on the plaster floor of the little bedroom. They could hear her distinctly:

“What’s the matter now?—what’s the matter with you, silly thing?”— her voice was much agitated, with an unreal gentleness.

“I thought it was some men come,” said the plaintive voice of the child. “Has he come?”

“Yes, they’ve brought him. There’s nothing to make a fuss about. Go to sleep now, like a good child.”

They could hear her voice in the bedroom, they waited whilst she covered the children under the bedclothes.

“Is he drunk?” asked the girl, timidly, faintly.

“No! No—he’s not! He—he’s asleep.”

“Is he asleep downstairs?”

“Yes—and don’t make a noise.”

There was silence for a moment, then the men heard the frightened child again:

“What’s that noise?”

“It’s nothing, I tell you, what are you bothering for?”

The noise was the grandmother moaning. She was oblivious of everything, sitting on her chair rocking and moaning. The manager put his hand on her arm and bade her “Sh—sh!!”

The old woman opened her eyes and looked at him. She was shocked by this interruption, and seemed to wonder.

“What time is it?”— the plaintive thin voice of the child, sinking back unhappily into sleep, asked this last question.

“Ten o’clock,” answered the mother more softly. Then she must have bent down and kissed the children.

Matthews beckoned to the men to come away. They put on their caps and took up the stretcher. Stepping over the body, they tiptoed out of the house. None of them spoke till they were far from the wakeful children.

When Elizabeth came down she found her mother alone on the parlour floor, leaning over the dead man, the tears dropping on him.

“We must lay him out,” the wife said. She put on the kettle, then returning knelt at the feet, and began to unfasten the knotted leather laces. The room was clammy and dim with only one candle, so that she had to bend her face almost to the floor. At last she got off the heavy boots and put them away.

“You must help me now,” she whispered to the old woman. Together they stripped the man.

When they arose, saw him lying in the naïve dignity of death, the women stood arrested in fear and respect. For a few moments they remained still, looking down, the old mother whimpering. Elizabeth felt countermanded. She saw him, how utterly inviolable he lay in himself. She had nothing to do with him. She could not accept it. Stooping, she laid her hand on him, in claim. He was still warm, for the mine was hot where he had died. His mother had his face between her hands, and was murmuring incoherently. The old tears fell in succession as drops from wet leaves; the mother was not weeping, merely her tears flowed. Elizabeth embraced the body of her husband, with cheek and lips. She seemed to be listening, inquiring, trying to get some connection. But she could not. She was driven away. He was impregnable.

She rose, went into the kitchen, where she poured warm water into a bowl, brought soap and flannel and a soft towel.

“I must wash him,” she said.

Then the old mother rose stiffly, and watched Elizabeth as she carefully washed his face, carefully brushing the big blond moustache from his mouth with the flannel. She was afraid with a bottomless fear, so she ministered to him. The old woman, jealous, said:

“Let me wipe him!”— and she kneeled on the other side drying slowly as Elizabeth washed, her big black bonnet sometimes brushing the dark head of her daughter. They worked thus in silence for a long time. They never forgot it was death, and the touch of the man’s dead body gave them strange emotions, different in each of the women; a great dread possessed them both, the mother felt the lie was given to her womb, she was denied; the wife felt the utter isolation of the human soul, the child within her was a weight apart from her.

At last it was finished. He was a man of handsome body, and his face showed no traces of drink. He was blonde, full-fleshed, with fine limbs. But he was dead.

“Bless him,” whispered his mother, looking always at his face, and speaking out of sheer terror. “Dear lad—bless him!” She spoke in a faint, sibilant ecstasy of fear and mother love.

Elizabeth sank down again to the floor, and put her face against his neck, and trembled and shuddered. But she had to draw away again. He was dead, and her living flesh had no place against his. A great dread and weariness held her: she was so unavailing. Her life was gone like this.

“White as milk he is, clear as a twelve-month baby, bless him, the darling!” the old mother murmured to herself. “Not a mark on him, clear and clean and white, beautiful as ever a child was made,” she murmured with pride. Elizabeth kept her face hidden.

“He went peaceful, Lizzie—peaceful as sleep. Isn’t he beautiful, the lamb? Ay— he must ha’ made his peace, Lizzie. ‘Appen he made it all right, Lizzie, shut in there. He’d have time. He wouldn’t look like this if he hadn’t made his peace. The lamb, the dear lamb. Eh, but he had a hearty laugh. I loved to hear it. He had the heartiest laugh, Lizzie, as a lad —”

Elizabeth looked up. The man’s mouth was fallen back, slightly open under the cover of the moustache. The eyes, half shut, did not show glazed in the obscurity. Life with its smoky burning gone from him, had left him apart and utterly alien to her. And she knew what a stranger he was to her. In her womb was ice of fear, because of this separate stranger with whom she had been living as one flesh. Was this what it all meant—utter, intact separateness, obscured by heat of living? In dread she turned her face away. The fact was too deadly. There had been nothing between them, and yet they had come together, exchanging their nakedness repeatedly. Each time he had taken her, they had been two isolated beings, far apart as now. He was no more responsible than she. The child was like ice in her womb. For as she looked at the dead man, her mind, cold and detached, said clearly: “Who am I? What have I been doing? I have been fighting a husband who did not exist. HE existed all the time. What wrong have I done? What was that I have been living with? There lies the reality, this man.”— And her soul died in her for fear: she knew she had never seen him, he had never seen her, they had met in the dark and had fought in the dark, not knowing whom they met nor whom they fought. And now she saw, and turned silent in seeing. For she had been wrong. She had said he was something he was not; she had felt familiar with him. Whereas he was apart all the while, living as she never lived, feeling as she never felt.

In fear and shame she looked at his naked body, that she had known falsely. And he was the father of her children. Her soul was torn from her body and stood apart. She looked at his naked body and was ashamed, as if she had denied it. After all, it was itself. It seemed awful to her. She looked at his face, and she turned her own face to the wall. For his look was other than hers, his way was not her way. She had denied him what he was—she saw it now. She had refused him as himself.— And this had been her life, and his life.—She was grateful to death, which restored the truth. And she knew she was not dead.

And all the while her heart was bursting with grief and pity for him. What had he suffered? What stretch of horror for this helpless man! She was rigid with agony. She had not been able to help him. He had been cruelly injured, this naked man, this other being, and she could make no reparation. There were the children—but the children belonged to life. This dead man had nothing to do with them. He and she were only channels through which life had flowed to issue in the children. She was a mother—but how awful she knew it now to have been a wife. And he, dead now, how awful he must have felt it to be a husband. She felt that in the next world he would be a stranger to her. If they met there, in the beyond, they would only be ashamed of what had been before. The children had come, for some mysterious reason, out of both of them. But the children did not unite them. Now he was dead, she knew how eternally he was apart from her, how eternally he had nothing more to do with her. She saw this episode of her life closed. They had denied each other in life. Now he had withdrawn. An anguish came over her. It was finished then: it had become hopeless between them long before he died. Yet he had been her husband. But how little! —

“Have you got his shirt, ‘Lizabeth?”

Elizabeth turned without answering, though she strove to weep and behave as her mother-in-law expected. But she could not, she was silenced. She went into the kitchen and returned with the garment.

“It is aired,” she said, grasping the cotton shirt here and there to try. She was almost ashamed to handle him; what right had she or anyone to lay hands on him; but her touch was humble on his body. It was hard work to clothe him. He was so heavy and inert. A terrible dread gripped her all the while: that he could be so heavy and utterly inert, unresponsive, apart. The horror of the distance between them was almost too much for her—it was so infinite a gap she must look across.

At last it was finished. They covered him with a sheet and left him lying, with his face bound. And she fastened the door of the little parlour, lest the children should see what was lying there. Then, with peace sunk heavy on her heart, she went about making tidy the kitchen. She knew she submitted to life, which was her immediate master. But from death, her ultimate master, she winced with fear and shame.

3.8.2: From The Rainbow

Chapter 1

How Tom Brangwen Married a Polish Lady

I

The Brangwens had lived for generations on the Marsh Farm, in the meadows where the Erewash twisted sluggishly through alder trees, separating Derbyshire from Nottinghamshire. Two miles away, a church-tower stood on a hill, the houses of the little country town climbing assiduously up to it. Whenever one of the Brangwens in the fields lifted his head from his work, he saw the church-tower at Ilkeston in the empty sky. So that as he turned again to the horizontal land, he was aware of something standing above him and beyond him in the distance.

There was a look in the eyes of the Brangwens as if they were expecting something unknown, about which they were eager. They had that air of readiness for what would come to them, a kind of surety, an expectancy, the look of an inheritor.

They were fresh, blond, slow-speaking people, revealing themselves plainly, but slowly, so that one could watch the change in their eyes from laughter to anger, blue, lit-up laughter, to a hard blue-staring anger; through all the irresolute stages of the sky when the weather is changing.

Living on rich land, on their own land, near to a growing town, they had forgotten what it was to be in straitened circumstances. They had never become rich, because there were always children, and the patrimony was divided every time. But always, at the Marsh, there was ample.

So the Brangwens came and went without fear of necessity, working hard because of the life that was in them, not for want of the money. Neither were they thriftless. They were aware of the last halfpenny, and instinct made them not waste the peeling of their apple, for it would help to feed the cattle. But heaven and earth was teeming around them, and how should this cease? They felt the rush of the sap in spring, they knew the wave which cannot halt, but every year throws forward the seed to begetting, and, falling back, leaves the young-born on the earth. They knew the intercourse between heaven and earth, sunshine drawn into the breast and bowels, the rain sucked up in the daytime, nakedness that comes under the wind in autumn, showing the birds’ nests no longer worth hiding. Their life and interrelations were such; feeling the pulse and body of the soil, that opened to their furrow for the grain, and became smooth and supple after their ploughing, and clung to their feet with a weight that pulled like desire, lying hard and unresponsive when the crops were to be shorn away. The young corn waved and was silken, and the lustre slid along the limbs of the men who saw it. They took the udder of the cows, the cows yielded milk and pulse against the hands of the men, the pulse of the blood of the teats of the cows beat into the pulse of the hands of the men. They mounted their horses, and held life between the grip of their knees, they harnessed their horses at the wagon, and, with hand on the bridle-rings, drew the heaving of the horses after their will.

In autumn the partridges whirred up, birds in flocks blew like spray across the fallow, rooks appeared on the grey, watery heavens, and flew cawing into the winter. Then the men sat by the fire in the house where the women moved about with surety, and the limbs and the body of the men were impregnated with the day, cattle and earth and vegetation and the sky, the men sat by the fire and their brains were inert, as their blood flowed heavy with the accumulation from the living day.

The women were different. On them too was the drowse of blood-intimacy, calves sucking and hens running together in droves, and young geese palpitating in the hand while the food was pushed down their throttle. But the women looked out from the heated, blind intercourse of farm-life, to the spoken world beyond. They were aware of the lips and the mind of the world speaking and giving utterance, they heard the sound in the distance, and they strained to listen.

It was enough for the men, that the earth heaved and opened its furrow to them, that the wind blew to dry the wet wheat, and set the young ears of corn wheeling freshly round about; it was enough that they helped the cow in labour, or ferreted the rats from under the barn, or broke the back of a rabbit with a sharp knock of the hand. So much warmth and generating and pain and death did they know in their blood, earth and sky and beast and green plants, so much exchange and interchange they had with these, that they lived full and surcharged, their senses full fed, their faces always turned to the heat of the blood, staring into the sun, dazed with looking towards the source of generation, unable to turn round.

But the woman wanted another form of life than this, something that was not blood-intimacy. Her house faced out from the farm-buildings and fields, looked out to the road and the village with church and Hall and the world beyond. She stood to see the far-off world of cities and governments and the active scope of man, the magic land to her, where secrets were made known and desires fulfilled. She faced outwards to where men moved dominant and creative, having turned their back on the pulsing heat of creation, and with this behind them, were set out to discover what was beyond, to enlarge their own scope and range and freedom; whereas the Brangwen men faced inwards to the teeming life of creation, which poured unresolved into their veins.

Looking out, as she must, from the front of her house towards the activity of man in the world at large, whilst her husband looked out to the back at sky and harvest and beast and land, she strained her eyes to see what man had done in fighting outwards to knowledge, she strained to hear how he uttered himself in his conquest, her deepest desire hung on the battle that she heard, far off, being waged on the edge of the unknown. She also wanted to know, and to be of the fighting host.

At home, even so near as Cossethay, was the vicar, who spoke the other, magic language, and had the other, finer bearing, both of which she could perceive, but could never attain to. The vicar moved in worlds beyond where her own menfolk existed. Did she not know her own menfolk: fresh, slow, full-built men, masterful enough, but easy, native to the earth, lacking outwardness and range of motion. Whereas the vicar, dark and dry and small beside her husband, had yet a quickness and a range of being that made Brangwen, in his large geniality, seem dull and local. She knew her husband. But in the vicar’s nature was that which passed beyond her knowledge. As Brangwen had power over the cattle so the vicar had power over her husband. What was it in the vicar, that raised him above the common men as man is raised above the beast? She craved to know. She craved to achieve this higher being, if not in herself, then in her children.

That which makes a man strong even if he be little and frail in body, just as any man is little and frail beside a bull, and yet stronger than the bull, what was it? It was not money nor power nor position. What power had the vicar over Tom Brangwen—none. Yet strip them and set them on a desert island, and the vicar was the master. His soul was master of the other man’s. And why—why? She decided it was a question of knowledge.

The curate was poor enough, and not very efficacious as a man, either, yet he took rank with those others, the superior. She watched his children being born, she saw them running as tiny things beside their mother. And already they were separate from her own children, distinct. Why were her own children marked below the others? Why should the curate’s children inevitably take precedence over her children, why should dominance be given them from the start? It was not money, nor even class. It was education and experience, she decided.

It was this, this education, this higher form of being, that the mother wished to give to her children, so that they too could live the supreme life on earth. For her children, at least the children of her heart, had the complete nature that should take place in equality with the living, vital people in the land, not be left behind obscure among the labourers. Why must they remain obscured and stifled all their lives, why should they suffer from lack of freedom to move? How should they learn the entry into the finer, more vivid circle of life?

Her imagination was fired by the squire’s lady at Shelly Hall, who came to church at Cossethay with her little children, girls in tidy capes of beaver fur, and smart little hats, herself like a winter rose, so fair and delicate. So fair, so fine in mould, so luminous, what was it that Mrs. Hardy felt which she, Mrs. Brangwen, did not feel? How was Mrs. Hardy’s nature different from that of the common women of Cossethay, in what was it beyond them? All the women of Cossethay talked eagerly about Mrs. Hardy, of her husband, her children, her guests, her dress, of her servants and her housekeeping.

The lady of the Hall was the living dream of their lives, her life was the epic that inspired their lives. In her they lived imaginatively, and in gossiping of her husband who drank, of her scandalous brother, of Lord William Bentley her friend, member of Parliament for the division, they had their own Odyssey enacting itself, Penelope and Ulysses before them, and Circe and the swine and the endless web.

So the women of the village were fortunate. They saw themselves in the lady of the manor, each of them lived her own fulfilment of the life of Mrs. Hardy. And the Brangwen wife of the Marsh aspired beyond herself, towards the further life of the finer woman, towards the extended being she revealed, as a traveller in his self-contained manner reveals far-off countries present in himself. But why should a knowledge of far-off countries make a man’s life a different thing, finer, bigger? And why is a man more than the beast and the cattle that serve him? It is the same thing.

The male part of the poem was filled in by such men as the vicar and Lord William, lean, eager men with strange movements, men who had command of the further fields, whose lives ranged over a great extent. Ah, it was something very desirable to know, this touch of the wonderful men who had the power of thought and comprehension. The women of the village might be much fonder of Tom Brangwen, and more at their ease with him, yet if their lives had been robbed of the vicar, and of Lord William, the leading shoot would have been cut away from them, they would have been heavy and uninspired and inclined to hate. So long as the wonder of the beyond was before them, they could get along, whatever their lot. And Mrs. Hardy, and the vicar, and Lord William, these moved in the wonder of the beyond, and were visible to the eyes of Cossethay in their motion.

II

About 1840, a canal was constructed across the meadows of the Marsh Farm, connecting the newly-opened collieries of the Erewash Valley. A high embankment travelled along the fields to carry the canal, which passed close to the homestead, and, reaching the road, went over in a heavy bridge.

So the Marsh was shut off from Ilkeston, and enclosed in the small valley bed, which ended in a bushy hill and the village spire of Cossethay.

The Brangwens received a fair sum of money from this trespass across their land.

Then, a short time afterwards, a colliery was sunk on the other side of the canal, and in a while the Midland Railway came down the valley at the foot of the Ilkeston hill, and the invasion was complete. The town grew rapidly, the Brangwens were kept busy producing supplies, they became richer, they were almost tradesmen.

Still the Marsh remained remote and original, on the old, quiet side of the canal embankment, in the sunny valley where slow water wound along in company of stiff alders, and the road went under ash-trees past the Brangwens’ garden gate.

But, looking from the garden gate down the road to the right, there, through the dark archway of the canal’s square aqueduct, was a colliery spinning away in the near distance, and further, red, crude houses plastered on the valley in masses, and beyond all, the dim smoking hill of the town.

The homestead was just on the safe side of civilisation, outside the gate. The house stood bare from the road, approached by a straight garden path, along which at spring the daffodils were thick in green and yellow. At the sides of the house were bushes of lilac and guelder-rose and privet, entirely hiding the farm buildings behind.

At the back a confusion of sheds spread into the home-close from out of two or three indistinct yards. The duck-pond lay beyond the furthest wall, littering its white feathers on the padded earthen banks, blowing its stray soiled feathers into the grass and the gorse bushes below the canal embankment, which rose like a high rampart near at hand, so that occasionally a man’s figure passed in silhouette, or a man and a towing horse traversed the sky.

At first the Brangwens were astonished by all this commotion around them. The building of a canal across their land made them strangers in their own place, this raw bank of earth shutting them off disconcerted them. As they worked in the fields, from beyond the now familiar embankment came the rhythmic run of the winding engines, startling at first, but afterwards a narcotic to the brain. Then the shrill whistle of the trains re-echoed through the heart, with fearsome pleasure, announcing the far-off come near and imminent.

As they drove home from town, the farmers of the land met the blackened colliers trooping from the pit-mouth. As they gathered the harvest, the west wind brought a faint, sulphurous smell of pit-refuse burning. As they pulled the turnips in November, the sharp clink-clink-clink-clink-clink of empty trucks shunting on the line, vibrated in their hearts with the fact of other activity going on beyond them.

The Alfred Brangwen of this period had married a woman from Heanor, a daughter of the “Black Horse”. She was a slim, pretty, dark woman, quaint in her speech, whimsical, so that the sharp things she said did not hurt. She was oddly a thing to herself, rather querulous in her manner, but intrinsically separate and indifferent, so that her long lamentable complaints, when she raised her voice against her husband in particular and against everybody else after him, only made those who heard her wonder and feel affectionately towards her, even while they were irritated and impatient with her. She railed long and loud about her husband, but always with a balanced, easy-flying voice and a quaint manner of speech that warmed his belly with pride and male triumph while he scowled with mortification at the things she said.

Consequently Brangwen himself had a humorous puckering at the eyes, a sort of fat laugh, very quiet and full, and he was spoilt like a lord of creation. He calmly did as he liked, laughed at their railing, excused himself in a teasing tone that she loved, followed his natural inclinations, and sometimes, pricked too near the quick, frightened and broke her by a deep, tense fury which seemed to fix on him and hold him for days, and which she would give anything to placate in him. They were two very separate beings, vitally connected, knowing nothing of each other, yet living in their separate ways from one root.

There were four sons and two daughters. The eldest boy ran away early to sea, and did not come back. After this the mother was more the node and centre of attraction in the home. The second boy, Alfred, whom the mother admired most, was the most reserved. He was sent to school in Ilkeston and made some progress. But in spite of his dogged, yearning effort, he could not get beyond the rudiments of anything, save of drawing. At this, in which he had some power, he worked, as if it were his hope. After much grumbling and savage rebellion against everything, after much trying and shifting about, when his father was incensed against him and his mother almost despairing, he became a draughtsman in a lace-factory in Nottingham.

He remained heavy and somewhat uncouth, speaking with broad Derbyshire accent, adhering with all his tenacity to his work and to his town position, making good designs, and becoming fairly well-off. But at drawing, his hand swung naturally in big, bold lines, rather lax, so that it was cruel for him to pedgill away at the lace designing, working from the tiny squares of his paper, counting and plotting and niggling. He did it stubbornly, with anguish, crushing the bowels within him, adhering to his chosen lot whatever it should cost. And he came back into life set and rigid, a rare-spoken, almost surly man.

He married the daughter of a chemist, who affected some social superiority, and he became something of a snob, in his dogged fashion, with a passion for outward refinement in the household, mad when anything clumsy or gross occurred. Later, when his three children were growing up, and he seemed a staid, almost middle-aged man, he turned after strange women, and became a silent, inscrutable follower of forbidden pleasure, neglecting his indignant bourgeois wife without a qualm.

Frank, the third son, refused from the first to have anything to do with learning. From the first he hung round the slaughter-house which stood away in the third yard at the back of the farm. The Brangwens had always killed their own meat, and supplied the neighbourhood. Out of this grew a regular butcher’s business in connection with the farm.

As a child Frank had been drawn by the trickle of dark blood that ran across the pavement from the slaughter-house to the crew-yard, by the sight of the man carrying across to the meat-shed a huge side of beef, with the kidneys showing, embedded in their heavy laps of fat.

He was a handsome lad with soft brown hair and regular features something like a later Roman youth. He was more easily excitable, more readily carried away than the rest, weaker in character. At eighteen he married a little factory girl, a pale, plump, quiet thing with sly eyes and a wheedling voice, who insinuated herself into him and bore him a child every year and made a fool of him. When he had taken over the butchery business, already a growing callousness to it, and a sort of contempt made him neglectful of it. He drank, and was often to be found in his public house blathering away as if he knew everything, when in reality he was a noisy fool.

Of the daughters, Alice, the elder, married a collier and lived for a time stormily in Ilkeston, before moving away to Yorkshire with her numerous young family. Effie, the younger, remained at home.

The last child, Tom, was considerably younger than his brothers, so had belonged rather to the company of his sisters. He was his mother’s favourite. She roused herself to determination, and sent him forcibly away to a grammar-school in Derby when he was twelve years old. He did not want to go, and his father would have given way, but Mrs. Brangwen had set her heart on it. Her slender, pretty, tightly-covered body, with full skirts, was now the centre of resolution in the house, and when she had once set upon anything, which was not often, the family failed before her.

So Tom went to school, an unwilling failure from the first. He believed his mother was right in decreeing school for him, but he knew she was only right because she would not acknowledge his constitution. He knew, with a child’s deep, instinctive foreknowledge of what is going to happen to him, that he would cut a sorry figure at school. But he took the infliction as inevitable, as if he were guilty of his own nature, as if his being were wrong, and his mother’s conception right. If he could have been what he liked, he would have been that which his mother fondly but deludedly hoped he was. He would have been clever, and capable of becoming a gentleman. It was her aspiration for him, therefore he knew it as the true aspiration for any boy. But you can’t make a silk purse out of a sow’s ear, as he told his mother very early, with regard to himself; much to her mortification and chagrin.

When he got to school, he made a violent struggle against his physical inability to study.

He sat gripped, making himself pale and ghastly in his effort to concentrate on the book, to take in what he had to learn. But it was no good. If he beat down his first repulsion, and got like a suicide to the stuff, he went very little further. He could not learn deliberately. His mind simply did not work.

In feeling he was developed, sensitive to the atmosphere around him, brutal perhaps, but at the same time delicate, very delicate. So he had a low opinion of himself. He knew his own limitation. He knew that his brain was a slow hopeless good-for-nothing.

So he was humble.

But at the same time his feelings were more discriminating than those of most of the boys, and he was confused. He was more sensuously developed, more refined in instinct than they. For their mechanical stupidity he hated them, and suffered cruel contempt for them. But when it came to mental things, then he was at a disadvantage. He was at their mercy. He was a fool. He had not the power to controvert even the most stupid argument, so that he was forced to admit things he did not in the least believe.

And having admitted them, he did not know whether he believed them or not; he rather thought he did.

But he loved anyone who could convey enlightenment to him through feeling. He sat betrayed with emotion when the teacher of literature read, in a moving fashion, Tennyson’s “Ulysses”, or Shelley’s “Ode to the West Wind”. His lips parted, his eyes filled with a strained, almost suffering light. And the teacher read on, fired by his power over the boy. Tom Brangwen was moved by this experience beyond all calculation, he almost dreaded it, it was so deep. But when, almost secretly and shamefully, he came to take the book himself, and began the words “Oh wild west wind, thou breath of autumn’s being,” the very fact of the print caused a prickly sensation of repulsion to go over his skin, the blood came to his face, his heart filled with a bursting passion of rage and incompetence. He threw the book down and walked over it and went out to the cricket field. And he hated books as if they were his enemies. He hated them worse than ever he hated any person.

He could not voluntarily control his attention. His mind had no fixed habits to go by, he had nothing to get hold of, nowhere to start from. For him there was nothing palpable, nothing known in himself, that he could apply to learning. He did not know how to begin.

Therefore he was helpless when it came to deliberate understanding or deliberate learning.

He had an instinct for mathematics, but if this failed him, he was helpless as an idiot. So that he felt that the ground was never sure under his feet, he was nowhere. His final downfall was his complete inability to attend to a question put without suggestion. If he had to write a formal composition on the Army, he did at last learn to repeat the few facts he knew: “You can join the army at eighteen. You have to be over five foot eight.”

But he had all the time a living conviction that this was a dodge and that his common-places were beneath contempt. Then he reddened furiously, felt his bowels sink with shame, scratched out what he had written, made an agonised effort to think of something in the real composition style, failed, became sullen with rage and humiliation, put the pen down and would have been torn to pieces rather than attempt to write another word.

He soon got used to the Grammar School, and the Grammar School got used to him, setting him down as a hopeless duffer at learning, but respecting him for a generous, honest nature. Only one narrow, domineering fellow, the Latin master, bullied him and made the blue eyes mad with shame and rage. There was a horrid scene, when the boy laid open the master’s head with a slate, and then things went on as before. The teacher got little sympathy. But Brangwen winced and could not bear to think of the deed, not even long after, when he was a grown man.

He was glad to leave school. It had not been unpleasant, he had enjoyed the companionship of the other youths, or had thought he enjoyed it, the time had passed very quickly, in endless activity. But he knew all the time that he was in an ignominious position, in this place of learning. He was aware of failure all the while, of incapacity. But he was too healthy and sanguine to be wretched, he was too much alive. Yet his soul was wretched almost to hopelessness.

He had loved one warm, clever boy who was frail in body, a consumptive type. The two had had an almost classic friendship, David and Jonathan, wherein Brangwen was the Jonathan, the server. But he had never felt equal with his friend, because the other’s mind outpaced his, and left him ashamed, far in the rear. So the two boys went at once apart on leaving school. But Brangwen always remembered his friend that had been, kept him as a sort of light, a fine experience to remember.

Tom Brangwen was glad to get back to the farm, where he was in his own again. “I have got a turnip on my shoulders, let me stick to th’ fallow,” he said to his exasperated mother. He had too low an opinion of himself. But he went about at his work on the farm gladly enough, glad of the active labour and the smell of the land again, having youth and vigour and humour, and a comic wit, having the will and the power to forget his own shortcomings, finding himself violent with occasional rages, but usually on good terms with everybody and everything.

When he was seventeen, his father fell from a stack and broke his neck. Then the mother and son and daughter lived on at the farm, interrupted by occasional loud-mouthed lamenting, jealous-spirited visitations from the butcher Frank, who had a grievance against the world, which he felt was always giving him less than his dues.

Frank was particularly against the young Tom, whom he called a mardy baby, and Tom returned the hatred violently, his face growing red and his blue eyes staring. Effie sided with Tom against Frank. But when Alfred came, from Nottingham, heavy jowled and lowering, speaking very little, but treating those at home with some contempt, Effie and the mother sided with him and put Tom into the shade. It irritated the youth that his elder brother should be made something of a hero by the women, just because he didn’t live at home and was a lace-designer and almost a gentleman. But Alfred was something of a Prometheus Bound, so the women loved him. Tom came later to understand his brother better.

As youngest son, Tom felt some importance when the care of the farm devolved on to him. He was only eighteen, but he was quite capable of doing everything his father had done. And of course, his mother remained as centre to the house.

The young man grew up very fresh and alert, with zest for every moment of life. He worked and rode and drove to market, he went out with companions and got tipsy occasionally and played skittles and went to the little travelling theatres. Once, when he was drunk at a public house, he went upstairs with a prostitute who seduced him. He was then nineteen.