4.10: Punk Rock Revolution

- Page ID

- 226939

Image 4.38 Punk stencil. AlbertRA 6 june 2020. CC BY SA 4.0.

Modernism vs. Postmodernism

What began as a reaction, not a rejection, to the modernist dogma, the postmodern movement erased the idea that graphic design needed to follow the rules in order to be successful (Keedy, 1998). Modernism focused on functionality and order, while postmodernism became the poster child of deconstruction. Modernism reflected an organized, no-nonsense art of design while postmodernism came along to destroy modernist values (Keedy, 1998). What modernism lacked was personal expression and resulted in designs that lacked humanization (Outhouse, 2013). Feelings of being stifled by rules, such as Gestalt theory, is what led a new generation of designers to express themselves in unique ways. There are No Rules Postmodernism does not cover a “coherent theory or ideology, a specific set of social institutions, a bounded collectivity or any other clear-cut part of reality” (Wilterdink, 2002). Instead, it becomes a conceptual experience (Outhouse, 2013). The authenticity and deconstruction of postmodernism makes it accessible to those unfamiliar with the rules that most graphic designers follow. Postmodernism seeks to destabilize concepts such as presence and identity and diminish the univocity of meaning (Aylesworth, 2015). The design movement comprises the use of multiple weights in typography, popular culture imagery that has been deconstructed and no clear form of unity.

Anti-Establishment: The New Counterculture

With this newfound creative movement, another movement was forming in the underground music scene; punk. Postmodernism and the punk subculture of the 20th century philosophies are tied in many ways. Both movements believe in authenticity, whether it be of art or social behavior and the Punk DIY aesthetic is represented in much of the postmodern graphic design movement’s artists and work. The timelines of each movement also line up nearly perfectly. Beginning in the late 1960s, blooming by the late 1970s and evolving throughout the 1980s and 1990s, both postmodernism and punk established themselves in their respective cultures (Wilterdink, 2002).

The Punk Movement No Future

The disenfranchised youth of the late 1970s sought to express themselves in a way that derived them from conformity (Chantry, 2015). The punk movement formed as a rejection of modern ideals and the acceptance of individuals who were deemed different from society (Smith, Dines & Parkinson, 2018). Punk values stem from individual freedoms and authenticity. This subculture was true to their values and philosophies of anti-establishment and anti-authoritarianism, basically the youth did not want to be suppressed by authority, they wanted to express themselves in ways that were not always socially acceptable (Errickson, 1999). Punks were individualists who refused to follow along to modern traditional values. They rejected authority and were strongly anti-establishment. Their dismissal of tradition is comparable to postmodernism’s desire to go against the rules. The punk cultural rebellion had a large impact in the design world that critics did not believe would occur (Chantry, 2015). DIY Art Every part of punk culture is meant to be a statement and represent their philosophies, whether that be commentary on government, religion or other traditional values, punks had something to say and in the most offensive way possible. “Clothing and the use of horrific symbols as jewelry speak to their philosophy. Punks wear the sign of the anarchists (an “A” surrounded by a circle), not to necessarily say they are anarchists, but to imply that they hate the idea of organized government” (Errickson, 1999, p.13). Punk design is similar in the sense that it aims to challenge traditional forms. Fanzines became increasingly popular in the punk subculture and also faced the criticism of having ugly design. The punk aesthetic relished in having repelling visuals in their art, clothing and music (Errickson, 1999) in order to prove that they were not conformists to the traditional ideals of beauty.

Impact in the Art World

The punk culture centered around the music, it was loud, aggressive and offensive, the music is what united punks around the world. Bands like, The Ramones, the Sex Pistols and Siouxie Sous and the Banshies established the punk culture in the art world. It was against everything mainstream, but their impact on the art and music world cannot be denied. To this day, musicians emulate these artists and have pushed the punk music scene in new directions. The punk aesthetic had been adopted into late postmodern designs of the 90s thanks to designers such as Jamie Reid and David Carson. These designers adopted the no rules aesthetic of punk culture and bridged the gap between punk and postmodern (Chantry, 2015).

The distorted guitar sounds, rough recording techniques, and simple song structures of early 1970’s punk bands like the Clash and the Sex Pistols have become iconic. What was once a subculture condemned by political figures like Margret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan, and occupied the dark, dingy basements of outcast friend groups, has become hugely popular with cultural relics now being sold alongside tea towels of the royal family. Now in the twentyfirst century, it remains difficult to define punk culture because of the differences in music and styles associated with the term. However, combined with its politically polarizing and anti-establishment lyrics, performances, and acts of rebellion, punk culture has become ripe for the academic spotlight subjecting it to various forms of analysis and critique. This has resulted in a whole discourse of postmodern interpretations of punk music, style, language, performance, art, and politics.

Despite this, little research is critical of linking punk’s key actors, characteristics, and ideas to world politics through a postmodern lens. This article will serve to problematize postmodern attributes of punk to argue that it never really was the anti-racist, counter-hegemonic, and socio-politically resistant force many academics and participants claimed it to be. It has been found that some bands which do not have the same history of structural whiteness as those frequently spotlighted in postmodern interpretations, appear to form a counter-hegemonic culture based on lived experiences and real discourse, however, as this article will show, they too do not fit postmodern categorizations.

This article contains three sections (or verses). The first verse will introduce the concept of postmodernism and how it has been applied to not just punk, but also world politics, cultural studies, and music. Second, the connection between punk culture, music and world politics will serve to problematize attributes of punk deemed postmodern, specifically how different readings of punk culture either support or contradict the postmodern canon. Third, aspects of punk that contradict its previously ascribed postmodern attributes will be expanded upon, focusing on the culture’s anti-racist mythos and individualized agency to further make the connection to world politics. This article has included quotes from punk figures under section titles so that they remain central to the argument. As oftentimes in academic punk studies, punks seem far removed from the discussion and are not treated as integral components. The quotes still serve to embody the key points made in each section and will continue to guide the reader throughout.

First Verse: Postmodern Interpretations Abound

Questioning anything and everything, to me, is punk rock. – Henry Rollins, former vocalist of Black Flag, no date. This section will introduce key concepts of postmodernism originating in the 1970s. It will specifically show how postmodernism has been applied to the concepts of world politics, cultural studies, and music. The purpose of this section is not to debate the merits of postmodernism and whether it accurately describes the contemporary state of the world. Rather, this section will serve to create a more nuanced understanding of postmodernism as a theory and cultural practice that is important and far-reaching, but nonetheless still in debate. Although this article seeks to problematize scholarship that views punk as a postmodern phenomenon (see Moore 2004; Patton, 2018), it cannot be refuted that like punk, postmodernism remains contentious in debates around world politics and popular culture. This is an important quality shared by both postmodernism and punk which will be touched upon at the end of this section. In this article, the term “postmodern” is understood from two key tendencies.

First, it suggests a deconstruction of boundaries between “high” and “low” culture, using a practice called “bricolage” to recombine formerly incompatible styles. In cultural studies, this collapse of cultural distinctions has been attributed to the commodification of all cultural products under global capitalism (Harvey, 1989). In the music and art scene, postmodernism can be characterized by its intertextuality, or its ability to (re)create with objects and images from the past by allocating aspects from previous texts within both the modern and “original” (Jameson, 1991: 280-285).

Second, it indicates the rejection of universal vantage points for understanding the world. This is especially useful in the social sciences, where postmodernism represents the deconstruction of metanarratives found in the previous modernist canon replaced with localized, self-reflexive, and contingent analyses in the search for truth (Lyotard et al., 1984: 11-23). Furthermore, in politics, postmodernism can signify a sense of revolutionary socio-political agency based not in class politics, but in the fragmented collection of identities and differences of new social movements (Melucci et al., 1989; Gitlin, 1995). While the merits of postmodernism and its contributions to the wider social sciences and humanities are still debated upon, its defining characteristics are important for understanding why it has been applied to punk in past scholarship.

From these two central tendencies, it is clear why scholars have touched upon the seemingly intrinsic qualities that punk, a culture defined by questioning the status-quo with acts of rebellion and resistance, shares with postmodernism. In fact, they gained increasing popularity and were developed in tandem throughout much of the 1970s and 1980s (Patton: 2018, 3). However, like the concept of postmodernism itself, there has been considerable debate about punk’s postmodern attributes. Moore (2004) argues that competing tendencies within punk (e.g. nihilism, cynicism, sincerity, independence) are all reactions to the same crises of postmodern society. While others have only found partial evidence for deeming punk as postmodern because the realities of its participants are subjective and difficult to categorize as postmodern (Muggleton, 2000). The Subcultures Network, based at the University of Reading, argues that punk is best understood from its inherent points of tension like avant-gardism and popularism, artificiality and realism, or individualism and collectivism (Worley et al., 2016: 7).

From past work, it should be clear that punk does not fit neatly into a postmodern categorization. However, what makes something “postmodern” is still debated amongst the theory’s leading figures, especially for matters concerning culture and music. Kramer (2002: 13-14) argues that postmodern theory contains “a maddeningly imprecise musical concept”. To better understand what makes music “postmodern”, he suggests viewing postmodernism not as a historical period, but as an attitude that influences not only contemporary musical practices but also how we use music of past generations . Furthermore, in punk scholarship, it is similarly argued that the culture is best defined as an ongoing attitude and not a scene that temporarily occupied a certain space in time before dissolving (Furness, 2012).

Postmodernism and punk viewed as ongoing attitudes reveals a path forward to more nuanced interpretations of how the two relate. This is especially important moving forward because while definitions of postmodernism and punk remain elusive, their connection remains persistent throughout academia.

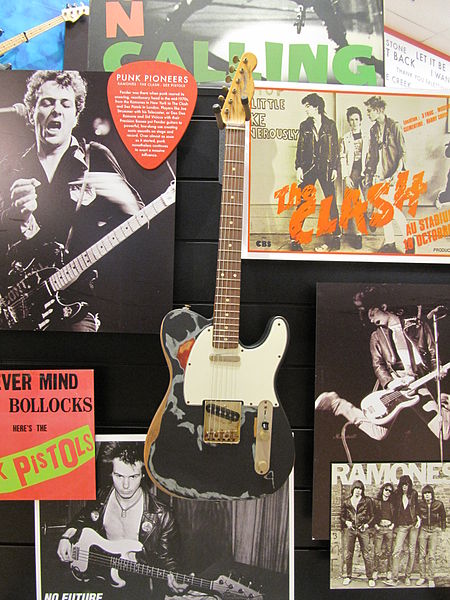

Image 4.49 Fender Guitar Factory Musuem. 9 Nov 2011. Flickr. Mr. Littlehand CC BY 2.0.

Remixed from:

Postmodernism & Punk: Examining a Counterculture’s Significance: The Creation of a Digital Exhibit Item Type Thesis Authors Manley, Taylor May 1, 2020. Download date 22/08/2022 19:35:51 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12648/1667. CC0.

Punk AF: Resisting Postmodern Interpretations of Punk Culture in World Politics Written by Patterson Deppen https://www.e-ir.info/2021/01/21/pun...orld-politics/ PATTERSON DEPPEN, JAN 21 2021 CC BY-NC 4.0.