1.4: Modern Art

- Page ID

- 226910

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

HOW TO ANALYZE AND INTERPRET ART: FORMAL OR CRITICAL ANALYSIS

While restricting our attention only to a description of the formal elements of an artwork may at first seem limited or even tedious, a careful and methodical examination of the physical components of an artwork is an important first step in “decoding” its meaning. It is useful, therefore, to begin at the beginning. There are four aspects of a formal analysis: description, analysis, interpretation, and evaluation.

Description: What can we notice at first glance about a work of art? Is it two-dimensional or three-dimensional? What is the medium? What kinds of actions were required in its production? How big is the work? What are the elements of design used within it? Starting with line: is it soft or hard, jagged or straight, expressive or mechanical? How is line being used to describe space? Considering shape: are the shapes large or small, hard-edged or soft? What is the relationship between shapes? Do they compete with one another for prominence? What shapes are in front? Which ones fade into the background? Indicating mass and volume: if two-dimensional, what means if any are used to give the illusion that the presented forms have weight and occupy space? If three-dimensional, what space is occupied or filled by the work? What is the mass of the work?

Organizing space: does the artist use perspective? If so, what kind? If the work uses linear perspective, where are the horizon line and vanishing point(s) located? On texture: how is texture being used? Is it actual or implied texture? In terms of color: what kinds of colors are used? Is there a color scheme? Is the image overall light, medium, or dark?

Analysis: Once the elements of the artwork have been identified, next come questions of how these elements are related. How are the elements arranged? In other words, how have principles of design been employed? What elements in the work were used to create unity and provide variety? How have the elements been used to do so? What is the scale of the work? Is it larger or smaller than what it represents (if it does depict someone or something)? Are the elements within the work in proportion to one another? Is the work symmetrically or asymmetrically balanced? What is used within the artwork to create emphasis? Where are the areas of emphasis? How has movement been conveyed in the work, for example, through line or placement of figures? Are there any elements within the work that create rhythm? Are any shapes or colors repeated?

Interpretation: Interpretation comes as much from the individual viewer as it does from the artwork. It derives from the intersection of what an object symbolizes to the artist and what it means to the viewer. It also often records how the meaning of objects has been changed by time and culture. Interpretation, then, is a process of unfolding. A work that may seem to mean one thing on first inspection may come to mean something more when studied further. Just as when re-reading a favorite book or re-watching a favorite movie, we often notice things not seen on the first viewing; interpretations of art objects can also reveal themselves slowly. Claims about meaning can be made but are better when they are backed up with supporting evidence. Interpretations can also change and some interpretations are better than others.

Evaluation: All this work of description, analysis, and interpretation, is done with one goal in mind: to make an evaluation about a work of art. Just as interpretations vary, so do evaluations. Your evaluation includes what you have discovered about the work during your examination as well as what you have learned, about the work, yourself, and others in the process. Your reaction to the artwork is an important component of your evaluation: what do you feel when you look at it? And, do you like the work? How and why do you find it visually pleasing, in some way disturbing, emotionally engaging? Evaluating and judging contemporary works of art is more difficult than works that are hundreds or thousands of years old because the verdict of history has not yet been passed on them. Museums are full of paintings by contemporary artists who were considered the next Michelangelo but who have since faded from the cultural forefront. The best art of a culture and period is that work which exemplifies the thought of the age from which it derives. What we think about our own culture is probably not what will be thought of it a century from now. The art that we believe best embodies our time may or may not last. As time moves on, our evaluations and judgments of our own time may not prove to be the most accurate ones. We live in a world full of art, and it is almost impossible to avoid making evaluations—possibly mistaken—about its value. Nonetheless, informed evaluations are still possible and useful even in the short term.

Remixed from:

Sachant, Pamela; Blood, Peggy; LeMieux, Jeffery; and Tekippe, Rita, "Introduction to Art: Design, Context, and Meaning" (2016). Fine Arts Open Textbooks. 3. https://oer.galileo.usg.edu/arts-textbooks/3 CC BY SA.

CUBISM

Developed by Pablo Picasso and George Braque, Cubism is one of the most significant developments in the history of modern art.

Image 1.14 Picasso – “Cubism 1937" by oddsock is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Image 1.15

Pablo Picasso’s route to Cubism began with the simplification of forms inspired by African masks and ancient sculpture. The painter George Braque, associated with the Fauves, was deeply interested in the work of Paul Cézanne, the Post-Impressionist who relied on pure areas of blocky color rather than clearly defined linear forms that he then organized within the canvas disregarding perspectival accuracy.

Image 1.16 Georges Braque, “Guitar and glass" by f_snarfel is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

The collaboration between Picasso and Braque in the development of Cubism is legendary in the history of art. Their intense working relationship lasted months in which the artists visited each other daily to discuss their work. Soon, they stopped signing their individual works and only declared a painting finished when both agreed. Recognizing that what they were doing was the creation of something wholly new and modern, Picasso and Braque referred to each other jokingly as Orville and Wilbur Wright, the American brothers who pioneered the development of flight a few years ahead of the development of Cubism.

Image 1.17 Bermuda No. 2, The Schooner Cubist and Futurist art by Charles Demuth – 1917. WikiArt. CC0.

Remixed from:

“Week 7 / March 13: Cubism.” Introduction to the History of Modern Art, CUNY Academic Commons, 3 Jan. 2019, arh141.commons.gc.cuny.edu/week-7. CC BY-NC SA 4.0.

NON-REPRESENTATIONAL OR NON-OBJECTIVE ART

Recurrent strains of abstraction appear throughout the history of art, when artists elected to streamline, suppress, or de-emphasize reference to the phenomenal world. In the twentieth century, though, this approach took on different character in some instances, with a stated rejection of the art as related to the natural world and concerned instead with the art itself, to the processes by which it was made, and with the product as referring to these processes and artistic qualities rather than to some outside phenomenon: the observed world. Still, the art is never completely independent of some reference: the viewer might respond to the color, painterly effect, line quality, or some other aspect that is not necessarily associated with recognition of a particular physical object or “thing” but that relates to the qualities of the art in some way, that is, to some recognition of reference—although this recognition may be ephemeral and may be nameless. The response might be quite visceral or intellectual, nonetheless.

The development of this idea was perhaps an inevitable phase of the abstraction and explorations of the formal means that had been conducted by various movements that evolved in nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Stories abound about the era in art and the push from abstraction to non-representation, with several artists claiming to have led the breakthrough. The first artist to use the term nonobjective art, however, seems to have been Aleksandr Rodchenko (1890-1956, Russia), and its most active early theorist and writer was probably Vasily Kandinsky (1866-1944, Russia, lived Germany and France). The artistic climate fostered widespread experimentation, and the synergistic atmosphere was a seedbed for new ideas and modes of working. Rodchenko sought to affirm the independence of artistic process and the “constructive” approach to creating artworks that were self-referential, and he explored the possibilities in painting, drawing, photography, sculpture and graphic arts.

Kandinsky, also Russian but working in Germany, wrote an important treatise entitled Concerning the Spiritual in Art (1912) that was widely popular and soon translated from the original German into many languages. He explored color theory in relationship to music, logic, human emotion, and the spiritual underpinnings of the abstractions that for centuries had been viewed and absorbed through religious icons and popular folk prints in his native Russia. In the twentieth century Wassily Kandinsky is considered as the inventor of non-figurative art. Over a period of several years his paintings moved gradually away from figurative subjects. In 1910 he created the first completely abstract work of art - a watercolor - without any reference to reality. Wassily Kandinsky not only became the first abstract artist, he also promoted it as a theorist. In 1912 his book On the Spiritual in Art was published.

Image 1.18 On White II by Vassily Kandinsky – 1923. WikiArt. CC0.

Image 1.19

Image 1.20 Image 1.21

Piet Mondrian is an excellent example of an artist who used geometric shapes almost exclusively. In his Composition with Yellow, Blue and Red (1937-42), Mondrian, uses straight vertical and horizontal black lines to divide his canvas into rectangles of primary colors.

Image 1.22 Piet Mondrian, Composition with Yellow, Blue and Red, 1937–42, oil on canvas, 72.7 x 69.2 cm (Tate, CC-BY-NC-ND 3.0)

Remixed from:

Myers, Cerise. Ed. History of Modern Art. PressBooks. https://art104.pressbooks.com/ CC BY 4.0.

Sachant, Pamela; Blood, Peggy; LeMieux, Jeffery; and Tekippe, Rita, "Introduction to Art: Design, Context, and Meaning" (2016). Fine Arts Open Textbooks. 3. https://oer.galileo.usg.edu/arts-textbooks/3 CC BY SA.

FUTURISM

Image 1.23 Giacomo Balla (Italian, 1871-1958), Velocity of an Automobile (also Automobile Assembly Line), 1913, oil and ink on paper on board, 74 x 104 cm. CC0.

Once Cubism was introduced into the vocabulary of modern art, its effect was immediate as it influenced many dynamic experiments in abstract art. Italian Futurism is one of the movements that developed as a result of Cubism. The painting’s emphasis on dynamism is characteristic of Italian Futurism, as is the subject of modern urban life. The Futurists embraced the energy of the modern city, its crowds and electricity. They adopted Cubist techniques to convey the sense of movement in time, while rejecting what they considered the more static and analytic approach of Cubist painters. Whereas in Cubist paintings the use of multiple, fragmentary views of things suggests the viewer is moving around the object, in Futurist paintings it is the scene that is moving around the viewer.

This artistic experimentation was cut short with the outbreak of World War I, which begins in 1914, embroiling Europe in a cataclysmic conflict where the advancements of the modern industrial age are immediately shown to have devastating consequences.

Because of the economic losses and loss of life resulting from the war, there was a revolution in Russia that overthrew the monarchy and ushered in Communism as a governmental system. Artists associated with this are called Russian Constructivists.

Italian Futurism developed at the same time as Analytic Cubism around 1907-1911, but with different goals. While Cubism was engaged with conceptual ideas about form and perception in the modern world and then translating these ideas into a formal visual vocabulary, Italian Futurism was politically and culturally engaged with modernizing Italy.

The Italian Futurists extolled the importance of masculinity and technology in an accelerated Cubist variation reliant on faceted forms, short jagged brushstrokes and diagonal lines to reflect the sensation of speed. Their founder, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, who divided his early years between Paris and Milan, published frequent manifestoes in leading newspapers that attempted to pull his fellow Italians aggressively and forcefully into the modern era.

In the “Futurist Manifesto,” published on the front page of the French newspaper Le Figaro in 1909, Marinetti called for the demolition of museums and praised the beauty of industrial speed by describing a roaring car as more beautiful than the Victory of Samothrace, one of the most famous sculptures from ancient Greece on view in the Louvre Museum.

Image 1.24 I Saw the Figure 5 in Gold Cubist and Futurist art by Charles Demuth – 1928. WikiArt. CC0.

Charles Demuth (1883-1935, USA) painted The Figure 5 in Gold in 1928. (Figure 5.5) Demuth met poet and physician William Carlos Williams at the boarding house where they both lived in Philadelphia while studying at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. Demuth’s painting is one in a series of portraits of friends, paying homage to Williams and his 1916 poem “The Great Figure”:

Among the rain

and lights

I saw the figure 5

in gold

on a red

firetruck

moving

tense

unheeded

to gong clangs

siren howls

and wheels rumbling

through the dark city.

Williams described the inspiration for his poem as an encounter with a fire truck as it noisily sped along the streets of New York, abruptly shaking him from his inner thoughts to a jarring awareness of what was going on around him. Demuth chose to paint his portrait of Williams not as a likeness but with references to his friend, the poet. The dark, shadowed diagonal lines radiating from the center of his painting, punctuated by bright white circles, capture the jolt of the charging truck accompanied by the clamor of its bells. The accelerating beat of the figure 5 echoes the pounding of Williams’s heart as he was startled. It was the sight of the number in gold that Williams was first aware of at the scene, and Demuth uses the pulsing 5 to symbolically portray his friend, surrounded by the rush of red as bright as blood with his name, Bill, above as if flashing in red neon. For Demuth, that connection between his friend and his poetry told us far more about who Williams was than his physical appearance. A traditional portrait would show us what Williams looked like, but Demuth wanted to share with the viewer the experience of the poem the artist closely identified with his friend so that we would have an inner, deeper understanding of the poet. Demuth gave us his personal interpretation of Williams through the story, the narrative, that he tells us with the aid of “The Great Figure.”

Remixed from:

Myers, Cerise. Ed. History of Modern Art. PressBooks. https://art104.pressbooks.com/ CC BY 4.0.

Sachant, Pamela; Blood, Peggy; LeMieux, Jeffery; and Tekippe, Rita, "Introduction to Art: Design, Context, and Meaning" (2016). Fine Arts Open Textbooks. 3. https://oer.galileo.usg.edu/arts-textbooks/3 CC BY SA.

“Week 9 / March 27: Italian Futurism and Russian Constructivism.” Introduction to the History of Modern Art, CUNY Academic Commons, 3 Jan. 2019, arh141.commons.gc.cuny.edu/week-9. CC BY-NCSA 4.0.

FAUVISM “WILD BEASTS”

Image 1.25 Henri Matisse, The Green Line, 1905, oil on canvas, 40.5 x 32.5 cm (Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen). CC0 US only.

Fauvism developed in France to become the first new artistic style of the 20th century. In contrast to the dark, vaguely disturbing nature of much fin-de-siècle, or turn-of-the-century, Symbolist art, the Fauves produced bright cheery landscapes and figure paintings, characterized by pure vivid color and bold distinctive brushwork.

When shown at the 1905 Salon d’Automne (an exhibition organized by artists in response to the conservative policies of the official exhibitions, or salons) in Paris, the contrast to traditional art was so striking it led critic Louis Vauxcelles to describe the artists as “Les Fauves” or “wild beasts,” and thus the name was born. One of several Expressionist movements to emerge in the early 20th century, Fauvism was short lived, and by 1910, artists in the group had diverged toward more individual interests. Nevertheless, Fauvism remains significant for it demonstrated modern art’s ability to evoke intensely emotional reactions through radical visual form.

THE EXPRESSIVE POTENTIAL OF COLOR

The best known Fauve artists include Henri Matisse, André Derain, and Maurice Vlaminck who pioneered its distinctive style. Their early works reveal the influence of Post-Impressionist artists, especially Neo-Impressionists like Paul Signac, whose interest in color’s optical effects had led to a divisionist method of juxtaposing pure hues on canvas. The Fauves, however, lacked such scientific intent. They emphasized the expressive potential of color, employing it arbitrarily, not based on an object’s natural appearance.

In Luxe, calm et volupté (1904), for example, Matisse employed a pointillist style by applying paint in small dabs and dashes. Instead of the subtle blending of complimentary colors typical of Neo-Impressionism Seurat, for example, the combination of fiery oranges, yellows, greens and purple is almost overpowering in its vibrant impact.

Similarly, while paintings such as Vlaminck’s The River Seine at Chantou (1906) appear to mimic the spontaneous, active brushwork of Impressionism, the Fauves adopted a painterly approach to enhance their work’s emotional power, not to capture fleeting effects of color, light or atmosphere on their subjects. Their preference for landscapes, carefree figures and lighthearted subject matter reflects their desire to create an art that would appeal primarily to the viewers’ senses.

Image 1.26 Maurice de Vlaminck, The River Seine at Chatou, 1906, oil on canvas, 82.6 x 101.9 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York). CC0.

Paintings such as Matisse’s Bonheur de Vivre (1905-06) epitomize this goal. Bright colors and undulating lines pull our eye gently through the idyllic scene, encouraging us to imagine feeling the warmth of the sun, the cool of the grass, the soft touch of a caress, and the passion of a kiss. Like many modern artists, the Fauves also found inspiration in objects from Africa and other non-western cultures. Seen through a colonialist lens, the formal distinctions of African art reflected current notions of Primitivism–the belief that, lacking the corrupting influence of European civilization, non-western peoples were more in tune with the primal elements of nature.

Image 1.27 Henri Matisse, Bonheur de Vivre (Joy of Life), 1905-6, oil on canvas, 176.5 x 240.7 cm (Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia). CC0 US only.

Blue Nude (Souvenir of Biskra) of 1907 shows how Matisse combined his traditional subject of the female nude with the influence of primitive sources. The woman’s face appears mask-like in the use of strong outlines and harsh contrasts of light and dark, and the hard lines of her body recall the angled planar surfaces common to African sculpture. This distorted effect, further heightened by her contorted pose, clearly distinguishes the figure from the idealized odalisques of Ingres and painters of the past.

Image 1.28 Henri Matisse, The Blue Nude (Souvenir de Biskra), 1907, oil on canvas, 92.1 x 140.3 cm (Baltimore Museum of Art). CC0 US only.

The Fauves' interest in Primitivism reinforced their reputation as “wild beasts” who sought new possibilities for art through their exploration of direct expression, impactful visual forms and instinctual appeal.

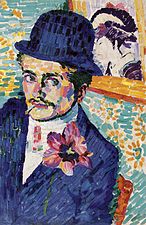

Image 1.29 L'homme à la tulipe (Portrait de Jean Metzinger) Fauvist painting by Jean Metzinger - 1906. WikiArt. CC0.

Remixed from:

“A Beginner’s Guide to Fauvism (Article).” Khan Academy, Khan Academy, www.khanacademy.org/humanities/art-1010/early-abstraction/fauvism-matisse/a/a-beginners-guide-to-fauvism. Accessed 6 May 2021. CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 US.