1.2: War and Revolution

- Page ID

- 226908

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

War World I

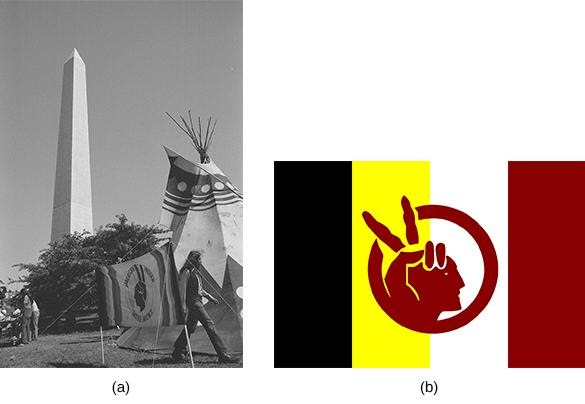

Image 1.1

Unlike his immediate predecessors, President Woodrow Wilson had planned to shrink the role of the United States in foreign affairs. He believed that the nation needed to intervene in international events only when there was a moral imperative to do so. But as Europe’s political situation grew dire, it became increasingly difficult for Wilson to insist that the conflict growing overseas was not America’s responsibility. Germany’s war tactics struck most observers as morally reprehensible, while also putting American free trade with the Entente at risk. Despite campaign promises and diplomatic efforts, Wilson could only postpone American involvement in the war.

WOODROW WILSON’S EARLY EFFORTS AT FOREIGN POLICY

When Woodrow Wilson took over the White House in March 1913, he promised a less expansionist approach to American foreign policy than Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft had pursued. Wilson did share the commonly held view that American values were superior to those of the rest of the world, that democracy was the best system to promote peace and stability, and that the United States should continue to actively pursue economic markets abroad. But he proposed an idealistic foreign policy based on morality, rather than American self-interest, and felt that American interference in another nation’s affairs should occur only when the circumstances rose to the level of a moral imperative.

Wilson appointed former presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan, a noted anti-imperialist and proponent of world peace, as his Secretary of State. Bryan undertook his new assignment with great vigor, encouraging nations around the world to sign “cooling off treaties,” under which they agreed to resolve international disputes through talks, not war, and to submit any grievances to an international commission. Bryan also negotiated friendly relations with Colombia, including a $25 million apology for Roosevelt’s actions during the Panamanian Revolution, and worked to establish effective self-government in the Philippines in preparation for the eventual American withdrawal. Even with Bryan’s support, however, Wilson found that it was much harder than he anticipated to keep the United States out of world affairs (Image 1.1). In reality, the United States was interventionist in areas where its interests—direct or indirect—were threatened.

Image 1.2 While Wilson strove to be less of an interventionist, he found that to be more difficult in practice than in theory. Here, a political cartoon depicts him as a rather hapless cowboy, unclear on how to harness a foreign challenge, in this case, Mexico.

Wilson’s greatest break from his predecessors occurred in Asia, where he abandoned Taft’s “dollar diplomacy,” a foreign policy that essentially used the power of U.S. economic dominance as a threat to gain favorable terms. Instead, Wilson revived diplomatic efforts to keep Japanese interference there at a minimum. But as World War I, also known as the Great War, began to unfold, and European nations largely abandoned their imperialistic interests in order to marshal their forces for self-defense, Japan demanded that China succumb to a Japanese protectorate over their entire nation. In 1917, William Jennings Bryan’s successor as Secretary of State, Robert Lansing, signed the Lansing-Ishii Agreement, which recognized Japanese control over the Manchurian region of China in exchange for Japan’s promise not to exploit the war to gain a greater foothold in the rest of the country.

Furthering his goal of reducing overseas interventions, Wilson had promised not to rely on the Roosevelt Corollary, Theodore Roosevelt’s explicit policy that the United States could involve itself in Latin American politics whenever it felt that the countries in the Western Hemisphere needed policing. Once president, however, Wilson again found that it was more difficult to avoid American interventionism in practice than in rhetoric. Indeed, Wilson intervened more in Western Hemisphere affairs than either Taft or Roosevelt. In 1915, when a revolution in Haiti resulted in the murder of the Haitian president and threatened the safety of New York banking interests in the country, Wilson sent over three hundred U.S. Marines to establish order. Subsequently, the United States assumed control over the island’s foreign policy as well as its financial administration. One year later, in 1916, Wilson again sent marines to Hispaniola, this time to the Dominican Republic, to ensure prompt payment of a debt that nation owed. In 1917, Wilson sent troops to Cuba to protect American-owned sugar plantations from attacks by Cuban rebels; this time, the troops remained for four years.

Wilson’s most noted foreign policy foray prior to World War I focused on Mexico, where rebel general Victoriano Huerta had seized control from a previous rebel government just weeks before Wilson’s inauguration. Wilson refused to recognize Huerta’s government, instead choosing to make an example of Mexico by demanding that they hold democratic elections and establish laws based on the moral principles he espoused. Officially, Wilson supported Venustiano Carranza, who opposed Huerta’s military control of the country. When American intelligence learned of a German ship allegedly preparing to deliver weapons to Huerta’s forces, Wilson ordered the U.S. Navy to land forces at Veracruz to stop the shipment.

On April 22, 1914, a fight erupted between the U.S. Navy and Mexican troops, resulting in nearly 150 deaths, nineteen of them American. Although Carranza’s faction managed to overthrow Huerta in the summer of 1914, most Mexicans—including Carranza—had come to resent American intervention in their affairs. Carranza refused to work with Wilson and the U.S. government, and instead threatened to defend Mexico’s mineral rights against all American oil companies established there. Wilson then turned to support rebel forces who opposed Carranza, most notably Pancho Villa (Image 1.3). However, Villa lacked the strength in number or weapons to overtake Carranza; in 1915, Wilson reluctantly authorized official U.S. recognition of Carranza’s government.

Image 1.3 Pancho Villa, a Mexican rebel who Wilson supported, then ultimately turned from, attempted an attack on the United States in retaliation. Wilson’s actions in Mexico were emblematic of how difficult it was to truly set the United States on a course of moral leadership.

As a postscript, an irate Pancho Villa turned against Wilson, and on March 9, 1916, led a fifteen-hundred-man force across the border into New Mexico, where they attacked and burned the town of Columbus. Over one hundred people died in the attack, seventeen of them American. Wilson responded by sending General John Pershing into Mexico to capture Villa and return him to the United States for trial. With over eleven thousand troops at his disposal, Pershing marched three hundred miles into Mexico before an angry Carranza ordered U.S. troops to withdraw from the nation. Although reelected in 1916, Wilson reluctantly ordered the withdrawal of U.S. troops from Mexico in 1917, avoiding war with Mexico and enabling preparations for American intervention in Europe. Again, as in China, Wilson’s attempt to impose a moral foreign policy had failed in light of economic and political realities.

WAR ERUPTS IN EUROPE

When a Serbian nationalist murdered the Archduke Franz Ferdinand of the Austro-Hungarian Empire on June 28, 1914, the underlying forces that led to World War I had already long been in motion and seemed, at first, to have little to do with the United States. At the time, the events that pushed Europe from ongoing tensions into war seemed very far away from U.S. interests. For nearly a century, nations had negotiated a series of mutual defense alliance treaties to secure themselves against their imperialistic rivals. Among the largest European powers, the Triple Entente included an alliance of France, Great Britain, and Russia. Opposite them, the Central powers, also known as the Triple Alliance, included Germany, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, and initially Italy. A series of “side treaties” likewise entangled the larger European powers to protect several smaller ones should war break out.

At the same time that European nations committed each other to defense pacts, they jockeyed for power over empires overseas and invested heavily in large, modern militaries. Dreams of empire and military supremacy fueled an era of nationalism that was particularly pronounced in the newer nations of Germany and Italy, but also provoked separatist movements among Europeans. The Irish rose up in rebellion against British rule, for example. And in Bosnia’s capital of Sarajevo, Gavrilo Princip and his accomplices assassinated the Austro-Hungarian archduke in their fight for a pan-Slavic nation. Thus, when Serbia failed to accede to Austro-Hungarian demands in the wake of the archduke’s murder, Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia with the confidence that it had the backing of Germany. This action, in turn, brought Russia into the conflict, due to a treaty in which they had agreed to defend Serbia. Germany followed suit by declaring war on Russia, fearing that Russia and France would seize this opportunity to move on Germany if it did not take the offensive. The eventual German invasion of Belgium drew Great Britain into the war, followed by the attack of the Ottoman Empire on Russia. By the end of August 1914, it seemed as if Europe had dragged the entire world into war.

The Great War was unlike any war that came before it. Whereas in previous European conflicts, troops typically faced each other on open battlefields, World War I saw new military technologies that turned war into a conflict of prolonged trench warfare. Both sides used new artillery, tanks, airplanes, machine guns, barbed wire, and, eventually, poison gas: weapons that strengthened defenses and turned each military offense into barbarous sacrifices of thousands of lives with minimal territorial advances in return. By the end of the war, the total military death toll was ten million, as well as another million civilian deaths attributed to military action, and another six million civilian deaths caused by famine, disease, or other related factors.

One terrifying new piece of technological warfare was the German unterseeboot—an “undersea boat” or U-boat. By early 1915, in an effort to break the British naval blockade of Germany and turn the tide of the war, the Germans dispatched a fleet of these submarines around Great Britain to attack both merchant and military ships. The U-boats acted in direct violation of international law, attacking without warning from beneath the water instead of surfacing and permitting the surrender of civilians or crew. By 1918, German U-boats had sunk nearly five thousand vessels. Of greatest historical note was the attack on the British passenger ship, RMS Lusitania, on its way from New York to Liverpool on May 7, 1915. The German Embassy in the United States had announced that this ship would be subject to attack for its cargo of ammunition: an allegation that later proved accurate. Nonetheless, almost 1,200 civilians died in the attack, including 128 Americans. The attack horrified the world, galvanizing support in England and beyond for the war (Image 1.4). This attack, more than any other event, would test President Wilson’s desire to stay out of what had been a largely European conflict.

Image 1.4 The torpedoing and sinking of the Lusitania, depicted in the English drawing above (a), resulted in the death over twelve hundred civilians and was an international incident that shifted American sentiment as to their potential role in the war, as illustrated in a British recruiting poster (b).

THE CHALLENGE OF NEUTRALITY

Despite the loss of American lives on the Lusitania, President Wilson stuck to his path of neutrality in Europe’s escalating war: in part out of moral principle, in part as a matter of practical necessity, and in part for political reasons. Few Americans wished to participate in the devastating battles that ravaged Europe, and Wilson did not want to risk losing his reelection by ordering an unpopular military intervention. Wilson’s “neutrality” did not mean isolation from all warring factions, but rather open markets for the United States and continued commercial ties with all belligerents. For Wilson, the conflict did not reach the threshold of a moral imperative for U.S. involvement; it was largely a European affair involving numerous countries with whom the United States wished to maintain working relations. In his message to Congress in 1914, the president noted that “Every man who really loves America will act and speak in the true spirit of neutrality, which is the spirit of impartiality and fairness and friendliness to all concerned.”

Wilson understood that he was already looking at a difficult reelection bid. He had only won the 1912 election with 42 percent of the popular vote, and likely would not have been elected at all had Roosevelt not come back as a third-party candidate to run against his former protégée Taft. Wilson felt pressure from all different political constituents to take a position on the war, yet he knew that elections were seldom won with a campaign promise of “If elected, I will send your sons to war!” Facing pressure from some businessmen and other government officials who felt that the protection of America’s best interests required a stronger position in defense of the Allied forces, Wilson agreed to a “preparedness campaign” in the year prior to the election. This campaign included the passage of the National Defense Act of 1916, which more than doubled the size of the army to nearly 225,000, and the Naval Appropriations Act of 1916, which called for the expansion of the U.S. fleet, including battleships, destroyers, submarines, and other ships.

As the 1916 election approached, the Republican Party hoped to capitalize on the fact that Wilson was making promises that he would not be able to keep. They nominated Charles Evans Hughes, a former governor of New York and sitting U.S. Supreme Court justice at the time of his nomination. Hughes focused his campaign on what he considered Wilson’s foreign policy failures, but even as he did so, he himself tried to walk a fine line between neutrality and belligerence, depending on his audience. In contrast, Wilson and the Democrats capitalized on neutrality and campaigned under the slogan “Wilson—he kept us out of war.” The election itself remained too close to call on election night. Only when a tight race in California was decided two days later could Wilson claim victory in his reelection bid, again with less than 50 percent of the popular vote. Despite his victory based upon a policy of neutrality, Wilson would find true neutrality a difficult challenge. Several different factors pushed Wilson, however reluctantly, toward the inevitability of American involvement.

A key factor driving U.S. engagement was economics. Great Britain was the country’s most important trading partner, and the Allies as a whole relied heavily on American imports from the earliest days of the war forward. Specifically, the value of all exports to the Allies quadrupled from $750 million to $3 billion in the first two years of the war. At the same time, the British naval blockade meant that exports to Germany all but ended, dropping from $350 million to $30 million. Likewise, numerous private banks in the United States made extensive loans—in excess of $500 million—to England. J. P. Morgan’s banking interests were among the largest lenders, due to his family’s connection to the country.

Another key factor complicating the decision to go to war was the deep ethnic divisions between native-born Americans and more recent immigrants. For those of Anglo-Saxon descent, the nation’s historic and ongoing relationship with Great Britain was paramount, but many Irish-Americans resented British rule over their place of birth and opposed support for the world’s most expansive empire. Millions of Jewish immigrants had fled anti-Semitic pogroms in Tsarist Russia and would have supported any nation fighting that authoritarian state. German Americans saw their nation of origin as a victim of British and Russian aggression and a French desire to settle old scores, whereas emigrants from Austria-Hungary and the Ottoman Empire were mixed in their sympathies for the old monarchies or ethnic communities that these empires suppressed. For interventionists, this lack of support for Great Britain and its allies among recent immigrants only strengthened their conviction.

Germany’s use of submarine warfare also played a role in challenging U.S. neutrality. After the sinking of the Lusitania, and the subsequent August 30 sinking of another British liner, the Arabic, Germany had promised to restrict their use of submarine warfare. Specifically, they promised to surface and visually identify any ship before they fired, as well as permit civilians to evacuate targeted ships. Instead, in February 1917, Germany intensified their use of submarines in an effort to end the war quickly before Great Britain’s naval blockade starved them out of food and supplies.

The German high command wanted to continue unrestricted warfare on all Atlantic traffic, including unarmed American freighters, in order to cripple the British economy and secure a quick and decisive victory. Their goal: to bring an end to the war before the United States could intervene and tip the balance in this grueling war of attrition. In February 1917, a German U-boat sank the American merchant ship, the Laconia, killing two passengers, and, in late March, quickly sunk four more American ships. These attacks increased pressure on Wilson from all sides, as government officials, the general public, and both Democrats and Republicans urged him to declare war.

The final element that led to American involvement in World War I was the so-called Zimmermann telegram. British intelligence intercepted and decoded a top-secret telegram from German foreign minister Arthur Zimmermann to the German ambassador to Mexico, instructing the latter to invite Mexico to join the war effort on the German side, should the United States declare war on Germany. It further went on to encourage Mexico to invade the United States if such a declaration came to pass, as Mexico’s invasion would create a diversion and permit Germany a clear path to victory. In exchange, Zimmermann offered to return to Mexico land that was previously lost to the United States in the Mexican-American War, including Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas (Image 1.5).

Image 1.5 “The Temptation,” which appeared in the Dallas Morning News on March 2, 1917, shows Germany as the Devil, tempting Mexico to join their war effort against the United States in exchange for the return of land formerly belonging to Mexico. The prospect of such a move made it all but impossible for Wilson to avoid war. (credit: Library of Congress)

The likelihood that Mexico, weakened and torn by its own revolution and civil war, could wage war against the United States and recover territory lost in the Mexican-American war with Germany’s help was remote at best. But combined with Germany’s unrestricted use of submarine warfare and the sinking of American ships, the Zimmermann telegram made a powerful argument for a declaration of war. The outbreak of the Russian Revolution in February and abdication of Tsar Nicholas II in March raised the prospect of democracy in the Eurasian empire and removed an important moral objection to entering the war on the side of the Allies. On April 2, 1917, Wilson asked Congress to declare war on Germany. Congress debated for four days, and several senators and congressmen expressed their concerns that the war was being fought over U.S. economic interests more than strategic need or democratic ideals. When Congress voted on April 6, fifty-six voted against the resolution, including the first woman ever elected to Congress, Representative Jeannette Rankin. This was the largest “no” vote against a war resolution in American history.

DEFINING AMERICAN

Wilson’s Peace without Victory Speech

Wilson’s last-ditch effort to avoid bringing the United States into World War I is captured in a speech he gave before the U.S. Senate on January 22, 1917. This speech, known as the “Peace without Victory” speech, extolled the country to be patient, as the countries involved in the war were nearing a peace. Wilson stated:

It must be a peace without victory. It is not pleasant to say this. I beg that I may be permitted to put my own interpretation upon it and that it may be understood that no other interpretation was in my thought. I am seeking only to face realities and to face them without soft concealments. Victory would mean peace forced upon the loser, a victor’s terms imposed upon the vanquished. It would be accepted in humiliation, under duress, at an intolerable sacrifice, and would leave a sting, a resentment, a bitter memory upon which terms of peace would rest, not permanently, but only as upon quicksand. Only a peace between equals can last, only a peace the very principle of which is equality and a common participation in a common benefit.

Not surprisingly, this speech was not well received by either side fighting the war. England resisted being put on the same moral ground as Germany, and France, whose country had been battered by years of warfare, had no desire to end the war without victory and its spoils. Still, the speech as a whole illustrates Wilson’s idealistic, if failed, attempt to create a more benign and high-minded foreign policy role for the United States. Unfortunately, the Zimmermann telegram and the sinking of the American merchant ships proved too provocative for Wilson to remain neutral. Little more than two months after this speech, he asked Congress to declare war on Germany.

Remixed from:

P. Scott Corbett (Ventura College), et al. U.S. History by OpenStax (Hardcover Version, Full Color). 1st ed., XanEdu Publishing Inc, 2014, openstax.org/books/us-history/pages/23-1 american-isolationism-and-the-european-origins-of-war. CC BY 4.0.

The lives of all Americans, whether they went abroad to fight or stayed on the home front, changed dramatically during the war. Restrictive laws censored dissent at home, and the armed forces demanded unconditional loyalty from millions of volunteers and conscripted soldiers. For organized labor, women, and African Americans in particular, the war brought changes to the prewar status quo. Some White women worked outside of the home for the first time, whereas others, like African American men, found that they were eligible for jobs that had previously been reserved for White men. African American women, too, were able to seek employment beyond the domestic servant jobs that had been their primary opportunity. These new options and freedoms were not easily erased after the war ended.

NEW OPPORTUNITIES BORN FROM WAR

After decades of limited involvement in the challenges between management and organized labor, the need for peaceful and productive industrial relations prompted the federal government during wartime to invite organized labor to the negotiating table. Samuel Gompers, head of the American Federation of Labor (AFL), sought to capitalize on these circumstances to better organize workers and secure for them better wages and working conditions. His efforts also solidified his own base of power. The increase in production that the war required exposed severe labor shortages in many states, a condition that was further exacerbated by the draft, which pulled millions of young men from the active labor force.

Wilson only briefly investigated the longstanding animosity between labor and management before ordering the creation of the National Labor War Board in April 1918. Quick negotiations with Gompers and the AFL resulted in a promise: Organized labor would make a “no-strike pledge” for the duration of the war, in exchange for the U.S. government’s protection of workers’ rights to organize and bargain collectively. The federal government kept its promise and promoted the adoption of an eight-hour workday (which had first been adopted by government employees in 1868), a living wage for all workers, and union membership. As a result, union membership skyrocketed during the war, from 2.6 million members in 1916 to 4.1 million in 1919. In short, American workers received better working conditions and wages, as a result of the country’s participation in the war. However, their economic gains were limited. While prosperity overall went up during the war, it was enjoyed more by business owners and corporations than by the workers themselves. Even though wages increased, inflation offset most of the gains. Prices in the United States increased an average of 15–20 percent annually between 1917 and 1920. Individual purchasing power actually declined during the war due to the substantially higher cost of living. Business profits, in contrast, increased by nearly a third during the war.

WOMEN IN WARTIME

For women, the economic situation was complicated by the war, with the departure of wage-earning men and the higher cost of living pushing many toward less comfortable lives. At the same time, however, wartime presented new opportunities for women in the workplace. More than one million women entered the workforce for the first time as a result of the war, while more than eight million working women found higher paying jobs, often in industry. Many women also found employment in what were typically considered male occupations, such as on the railroads (Image 1.6), where the number of women tripled, and on assembly lines. After the war ended and men returned home and searched for work, women were fired from their jobs, and expected to return home and care for their families. Furthermore, even when they were doing men’s jobs, women were typically paid lower wages than male workers, and unions were ambivalent at best—and hostile at worst—to women workers. Even under these circumstances, wartime employment familiarized women with an alternative to a life in domesticity and dependency, making a life of employment, even a career, plausible for women. When, a generation later, World War II arrived, this trend would increase dramatically.

Image 1.6 The war brought new opportunities to women, such as the training offered to those who joined the Land Army (a) or the opening up of traditionally male occupations. In 1918, Eva Abbott (b) was one of many new women workers on the Erie Railroad. However, once the war ended and veterans returned home, these opportunities largely disappeared. (credit b: modification of work by U.S. Department of Labor)

One notable group of women who exploited these new opportunities was the Women’s Land Army of America. First during World War I, then again in World War II, these women stepped up to run farms and other agricultural enterprises, as men left for the armed forces (Image 1.6). Known as Farmerettes, some twenty thousand women—mostly college educated and from larger urban areas—served in this capacity. Their reasons for joining were manifold. For some, it was a way to serve their country during a time of war. Others hoped to capitalize on the efforts to further the fight for women’s suffrage.

Also of special note were the approximately thirty thousand American women who served in the military, as well as a variety of humanitarian organizations, such as the Red Cross and YMCA, during the war. In addition to serving as military nurses (without rank), American women also served as telephone operators in France. Of this latter group, 230 of them, known as “Hello Girls,” were bilingual and stationed in combat areas. Over eighteen thousand American women served as Red Cross nurses, providing much of the medical support available to American troops in France. Close to three hundred nurses died during service. Many of those who returned home continued to work in hospitals and home healthcare, helping wounded veterans heal both emotionally and physically from the scars of war.

AFRICAN AMERICANS AND THE CRUSADE FOR DEMOCRACY

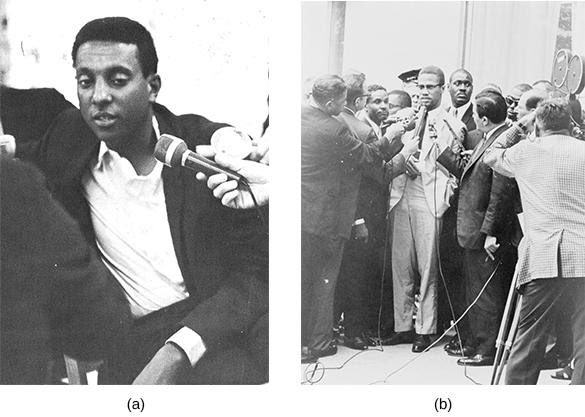

African Americans also found that the war brought upheaval and opportunity. Blacks composed 13 percent of the enlisted military, with 350,000 men serving. Colonel Charles Young of the Tenth Cavalry division served as the highest-ranking African American officer. Blacks served in segregated units and suffered from widespread racism in the military hierarchy, often serving in menial or support roles. Some troops saw combat, however, and were commended for serving with valor. The 369th Infantry, for example, known as the Harlem Hellfighters, served on the frontline of France for six months, longer than any other American unit. One hundred seventy-one men from that regiment received the Legion of Merit for meritorious service in combat. The regiment marched in a homecoming parade in New York City, was remembered in paintings (Image 1.7), and was celebrated for bravery and leadership. The accolades given to them, however, in no way extended to the bulk of African Americans fighting in the war.

Image 1.7 African American soldiers suffered under segregation and second-class treatment in the military. Still, the 369th Infantry earned recognition and reward for its valor in service both in France and the United States.

On the home front, African Americans, like American women, saw economic opportunities increase during the war. During the so-called Great Migration (discussed in a previous chapter), nearly 350,000 African Americans had fled the post-Civil War South for opportunities in northern urban areas. From 1910–1920, they moved north and found work in the steel, mining, shipbuilding, and automotive industries, among others. African American women also sought better employment opportunities beyond their traditional roles as domestic servants. By 1920, over 100,000 women had found work in diverse manufacturing industries, up from 70,000 in 1910.

Despite these opportunities, racism continued to be a major force in both the North and South. Worried that Black veterans would feel empowered to change the status quo of White supremacy, many White people took political, economic, and violent action against them. In a speech on the Senate floor in 1917, Mississippi Senator James K. Vardaman said, “Impress the negro with the fact that he is defending the flag, inflate his untutored soul with military airs, teach him that it is his duty to keep the emblem of the Nation flying triumphantly in the air—it is but a short step to the conclusion that his political rights must be respected.” Several municipalities passed residential codes designed to prohibit African Americans from settling in certain neighborhoods. Race riots also increased in frequency: In 1917 alone, there were race riots in twenty-five cities, including East Saint Louis, where thirty-nine Blacks were killed. In the South, White business and plantation owners feared that their cheap workforce was fleeing the region, and used violence to intimidate Blacks into staying. According to NAACP statistics, recorded incidences of lynching increased from thirty-eight in 1917 to eighty-three in 1919. Dozens of Black veterans were among the victims. The frequency of these killings did not start to decrease until 1923, when the number of annual lynchings dropped below thirty-five for the first time since the Civil War.

THE LAST VESTIGES OF PROGRESSIVISM

Across the United States, the war intersected with the last lingering efforts of the Progressives who sought to use the war as motivation for their final push for change. It was in large part due to the war’s influence that Progressives were able to lobby for the passage of the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Amendments to the U.S. Constitution. The Eighteenth Amendment, prohibiting alcohol, and the Nineteenth Amendment, giving women the right to vote, received their final impetus due to the war effort.

Prohibition, as the anti-alcohol movement became known, had been a goal of many Progressives for decades. Organizations such as the Women’s Christian Temperance Union and the Anti-Saloon League linked alcohol consumption with any number of societal problems, and they had worked tirelessly with municipalities and counties to limit or prohibit alcohol on a local scale. But with the war, prohibitionists saw an opportunity for federal action. One factor that helped their cause was the strong anti-German sentiment that gripped the country, which turned sympathy away from the largely German-descended immigrants who ran the breweries. Furthermore, the public cry to ration food and grain—the latter being a key ingredient in both beer and hard alcohol—made prohibition even more patriotic. Congress ratified the Eighteenth Amendment in January 1919, with provisions to take effect one year later. Specifically, the amendment prohibited the manufacture, sale, and transportation of intoxicating liquors. It did not prohibit the drinking of alcohol, as there was a widespread feeling that such language would be viewed as too intrusive on personal rights. However, by eliminating the manufacture, sale, and transport of such beverages, drinking was effectively outlawed. Shortly thereafter, Congress passed the Volstead Act, translating the Eighteenth Amendment into an enforceable ban on the consumption of alcoholic beverages, and regulating the scientific and industrial uses of alcohol. The act also specifically excluded from prohibition the use of alcohol for religious rituals (Image 1.8).

Image 1.8 Surrounded by prominent “dry workers,” Governor James P. Goodrich of Indiana signs a statewide bill to prohibit alcohol.

Unfortunately for proponents of the amendment, the ban on alcohol did not take effect until one full year following the end of the war. Almost immediately following the war, the general public began to oppose—and clearly violate—the law, making it very difficult to enforce. Doctors and druggists, who could prescribe whisky for medicinal purposes, found themselves inundated with requests. In the 1920s, organized crime and gangsters like Al Capone would capitalize on the persistent demand for liquor, making fortunes in the illegal trade. A lack of enforcement, compounded by an overwhelming desire by the public to obtain alcohol at all costs, eventually resulted in the repeal of the law in 1933.

The First World War also provided the impetus for another longstanding goal of some reformers: universal suffrage. Supporters of equal rights for women pointed to Wilson’s rallying cry of a war “to make the world safe for democracy,” as hypocritical, saying he was sending American boys to die for such principles while simultaneously denying American women their democratic right to vote (Image 1.8). Carrie Chapman Catt, president of the National American Women Suffrage Movement, capitalized on the growing patriotic fervor to point out that every woman who gained the vote could exercise that right in a show of loyalty to the nation, thus offsetting the dangers of draft-dodgers or naturalized Germans who already had the right to vote.

Alice Paul, of the National Women’s Party, organized more radical tactics, bringing national attention to the issue of women’s suffrage by organizing protests outside the White House and, later, hunger strikes among arrested protesters.

African American suffragists, who had been active in the movement for decades, faced discrimination from their White counterparts. Some White leaders justified this treatment based on the concern that promoting Black women would erode public support. But overt racism played a significant role, as well. During the suffrage parade in 1913, Black members were told to march at the rear of the line. Ida B. Wells-Barnett, a prominent voice for equality, first asked her local delegation to oppose this segregation; they refused. Not to be dismissed, Wells-Barnett waited in the crowd until the Illinois delegation passed by, then stepped onto the parade route and took her place among them. By the end of the war, the abusive treatment of suffragist hunger-strikers in prison, women’s important contribution to the war effort, and the arguments of his suffragist daughter Jessie Woodrow Wilson Sayre moved President Wilson to understand women’s right to vote as an ethical mandate for a true democracy. He began urging congressmen and senators to adopt the legislation. The amendment finally passed in June 1919, and the states ratified it by August 1920. Specifically, the Nineteenth Amendment prohibited all efforts to deny the right to vote on the basis of sex. It took effect in time for American women to vote in the presidential election of 1920.

Image 1.9 Suffragists picketed the White House in 1917, leveraging the war and America’s stance on democracy to urge Woodrow Wilson to support an amendment giving women the right to vote.

Remixed from:

P. Scott Corbett (Ventura College), et al. U.S. History by OpenStax (Hardcover Version, Full Color). 1st ed., XanEdu Publishing Inc, 2014, openstax.org/books/us-history/pages/23-3-a-new-home-front. CC BY 4.0.

The American role in World War I was brief but decisive. While millions of soldiers went overseas, and many thousands paid with their lives, the country’s involvement was limited to the very end of the war. In fact, the peace process, with the international conference and subsequent ratification process, took longer than the time U.S. soldiers were “in country” in France. For the Allies, American reinforcements came at a decisive moment in their defense of the western front, where a final offensive had exhausted German forces. For the United States, and for Wilson’s vision of a peaceful future, the fighting was faster and more successful than what was to follow.

WINNING THE WAR

When the United States declared war on Germany in April 1917, the Allied forces were close to exhaustion. Great Britain and France had already indebted themselves heavily in the procurement of vital American military supplies. Now, facing near-certain defeat, a British delegation to Washington, DC, requested immediate troop reinforcements to boost Allied spirits and help crush German fighting morale, which was already weakened by short supplies on the frontlines and hunger on the home front. Wilson agreed and immediately sent 200,000 American troops in June 1917. These soldiers were placed in “quiet zones” while they trained and prepared for combat.

By March 1918, the Germans had won the war on the eastern front. The Russian Revolution of the previous year had not only toppled the hated regime of Tsar Nicholas II but also ushered in a civil war from which the Bolshevik faction of Communist revolutionaries under the leadership of Vladimir Lenin emerged victorious. Weakened by war and internal strife, and eager to build a new Soviet Union, Russian delegates agreed to a generous peace treaty with Germany. Thus emboldened, Germany quickly moved upon the Allied lines, causing both the French and British to ask Wilson to forestall extensive training to U.S. troops and instead commit them to the front immediately. Although wary of the move, Wilson complied, ordering the commander of the American Expeditionary Force, General John “Blackjack” Pershing, to offer U.S. troops as replacements for the Allied units in need of relief. By May 1918, Americans were fully engaged in the war (Image 1.10).

Image 1.10 U.S. soldiers run past fallen Germans on their way to a bunker. In World War I, for the first time, photographs of the battles brought the war vividly to life for those at home.

In a series of battles along the front that took place from May 28 through August 6, 1918, including the battles of Cantigny, Chateau Thierry, Belleau Wood, and the Second Battle of the Marne, American forces alongside the British and French armies succeeded in repelling the German offensive. The Battle of Cantigny, on May 28, was the first American offensive in the war: In less than two hours that morning, American troops overran the German headquarters in the village, thus convincing the French commanders of their ability to fight against the German line advancing towards Paris. The subsequent battles of Chateau Thierry and Belleau Wood proved to be the bloodiest of the war for American troops. At the latter, faced with a German onslaught of mustard gas, artillery fire, and mortar fire, U.S. Marines attacked German units in the woods on six occasions—at times meeting them in hand-to-hand and bayonet combat—before finally repelling the advance. The U.S. forces suffered 10,000 casualties in the three-week battle, with almost 2,000 killed in total and 1,087 on a single day. Brutal as they were, they amounted to small losses compared to the casualties suffered by France and Great Britain. Still, these summer battles turned the tide of the war, with the Germans in full retreat by the end of July 1918 (Image 1.11).

Image 1.11 This map shows the western front at the end of the war, as the Allied Forces decisively break the German line.

MY STORY

Sgt. Charles Leon Boucher: Life and Death in the Trenches of France

Wounded in his shoulder by enemy forces, George, a machine gunner posted on the right end of the American platoon, was taken prisoner at the Battle of Seicheprey in 1918. However, as darkness set in that evening, another American soldier, Charlie, heard a noise from a gully beside the trench in which he had hunkered down. “I figured it must be the enemy mop-up patrol,” Charlie later said.

I only had a couple of bullets left in the chamber of my forty-five. The noise stopped and a head popped into sight. When I was about to fire, I gave another look and a white and distorted face proved to be that of George, so I grabbed his shoulders and pulled him down into our trench beside me. He must have had about twenty bullet holes in him but not one of them was well placed enough to kill him. He made an effort to speak so I told him to keep quiet and conserve his energy. I had a few malted milk tablets left and, I forced them into his mouth. I also poured the last of the water I had left in my canteen into his mouth.

Following a harrowing night, they began to crawl along the road back to their platoon. As they crawled, George explained how he survived being captured. Charlie later told how George “was taken to an enemy First Aid Station where his wounds were dressed. Then the doctor motioned to have him taken to the rear of their lines. But, the Sergeant Major pushed him towards our side and ‘No Mans Land,’ pulled out his Luger Automatic and shot him down. Then, he began to crawl towards our lines little by little, being shot at consistently by the enemy snipers till, finally, he arrived in our position.”

The story of Charlie and George, related later in life by Sgt. Charles Leon Boucher to his grandson, was one replayed many times over in various forms during the American Expeditionary Force’s involvement in World War I. The industrial scale of death and destruction was as new to American soldiers as to their European counterparts, and the survivors brought home physical and psychological scars that influenced the United States long after the war was won (Image 1.12).

Image 1.12 This photograph of U.S. soldiers in a trench hardly begins to capture the brutal conditions of trench warfare, where disease, rats, mud, and hunger plagued the men.

By the end of September 1918, over one million U.S. soldiers staged a full offensive into the Argonne Forest. By November—after nearly forty days of intense fighting—the German lines were broken, and their military command reported to German Emperor Kaiser Wilhelm II of the desperate need to end the war and enter into peace negotiations. Facing civil unrest from the German people in Berlin, as well as the loss of support from his military high command, Kaiser Wilhelm abdicated his throne on November 9, 1918, and immediately fled by train to the Netherlands. Two days later, on November 11, 1918, Germany and the Allies declared an immediate armistice, thus bring the fighting to a stop and signaling the beginning of the peace process.

When the armistice was declared, a total of 117,000 American soldiers had been killed and 206,000 wounded. The Allies as a whole suffered over 5.7 million military deaths, primarily Russian, British, and French men. The Central powers suffered four million military deaths, with half of them German soldiers. The total cost of the war to the United States alone was in excess of $32 billion, with interest expenses and veterans’ benefits eventually bringing the cost to well over $100 billion. Economically, emotionally, and geopolitically, the war had taken an enormous toll.

Remixed from:

P. Scott Corbett (Ventura College), et al. U.S. History by OpenStax (Hardcover Version, Full Color). 1st ed., XanEdu Publishing Inc, 2014, openstax.org/books/us-history/pages/23-4-from war-to-peace. CC BY 4.0.

THE RUSSIAN REVOLUTION

The Russian revolutions of 1905 and 1917 reshaped the country's political institutions and led to a century of conflict with the West. During the 1905 revolution, Russian liberals challenged the absolute authority of the Russian tsar, when a coalition of workers and middle-class Russians used economic and political means to demand democratic concessions. While their gains were temporary, they inspired the future Bolshevik revolutionaries.

In February 1917, during the height of World War I, a coalition of Russian liberals and socialists challenged Russia's autocratic government and organized a series of general strikes and political protests which forced Tsar Nicholas to abdicate. The leaders created a weak provisional national government, while socialist officials organized local soviets (political councils) of Russian's industrial workers. These factions soon came into conflict.

By October 1917, the Bolshevik Party, a communist organization led by Vladimir Lenin, staged a revolution against the provisional government and seized control of the state. The Bolsheviks used military force to consolidate power and establish control over the local soviets. Throughout the 1920s, Lenin and his successor Joseph Stalin used violence and political control to impose communism on Russia's political, economic, and social institutions. Communist leaders also tried to export the revolution by supporting communist political organizations in Europe and the United States.

Artistic innovation had smoldered before the revolution. Artists such as Lyubov Popova, Natalia Goncharova, Mikhail Larionov, Alexander Rodchenko and David Burliuk had produced striking avant-garde works earlier than 1917, as had Wassily Kandinsky, Kazimir Malevich and Marc Chagall. Distracted by having to fight a world war and by domestic unrest, the Tsarist regime had let art slip the leash. The conflict had reduced Russia’s contacts with the West and native talent had taken new directions. Several significant works by Malevich in the exhibition, including Red Square(below) – a red parallelogram, stark and challenging on a white ground – and Dynamic Suprematism Supremus (below), with its vortex of geometric shapes, date from the years before the revolution.

But it was 1917, with its promise of brave new worlds and liberation from the past, that set all the arts aflame. The poets Alexander Blok, Andrei Bely and Sergei Yesenin produced their most important work. Authors such as Mikhail Zoshchenko and Mikhail Bulgakov pushed at the bounds of satire and fantasy. The Futurist poets, chief among them Vladimir Mayakovsky, embraced the revolution while proclaiming the renewal of art. The Poputchiki or Fellow Travellers – writers nominally sympathetic to Bolshevism but nervous about commitment – clashed with the self-described Proletarian writers who brashly claimed the right to speak for the Party. Musical experimentalism broke through the barriers of harmony, overflowed into jazz and created orchestras without conductors. The watchwords were novelty and invention, with pre-revolutionary forms raucously jettisoned from the steamship of modernity.

Remixed from:

“Unit 7: Revolutionary Russia: Marxist Theory and Agrarian Realities.” OER Commons, Saylor Academy.org, www.oercommons.org/courses/modern-revolutions/view. Accessed 3 May 2021.CC BY 4.0.

REVOLUTIONARY RUSSIA: MARXIST THEORY AND AGRARIAN REALITIES

The Russian revolutions of 1905 and 1917 reshaped the country's political institutions and led to a century of conflict with the West. During the 1905 revolution, Russian liberals challenged the absolute authority of the Russian tsar, when a coalition of workers and middle-class Russians used economic and political means to demand democratic concessions. While their gains were temporary, they inspired the future Bolshevik revolutionaries.

In February 1917, during the height of World War I, a coalition of Russian liberals and socialists challenged Russia's autocratic government and organized a series of general strikes and political protests which forced Tsar Nicholas to abdicate. The leaders created a weak provisional national government, while socialist officials organized local soviets (political councils) of Russian's industrial workers. These factions soon came into conflict.

By October 1917, the Bolshevik Party, a communist organization led by Vladimir Lenin, staged a revolution against the provisional government and seized control of the state. The Bolsheviks used military force to consolidate power and establish control over the local soviets. Throughout the 1920s, Lenin and his successor Joseph Stalin used violence and political control to impose communism on Russia's political, economic, and social institutions. Communist leaders also tried to export the revolution by supporting communist political organizations in Europe and the United States.

Attribution:

Sixsmith, Martin. “The Story of Art in the Russian Revolution.” The Royal Academy of Art, 20 Dec. 2016, www.royalacademy.org.uk/article/art-and-the-russian-revolution. CC BY NC-ND 3.0.