8.3: Depression Decade- The 1930s

- Page ID

- 127011

By 1928, the economy showed signs of slowing, both in California and across the nation. In fact, much of American agriculture had never shared in the prosperity, though California growers had fared relatively better than their counterparts elsewhere in the country. As early as 1926, the southern California construction boom began to level off. The price of stock in Giannini’s banks dropped sharply in mid-1928. Then, on October 24, 1929, prices on the New York Stock Exchange fell, and continued to decline over the next weeks, months, and years. Businesses failed. Unemployment mounted, especially for manufacturing workers. Those who kept their jobs often worked fewer hours and at reduced wages. People were evicted from their homes when they could not make their rent or mortgage payments. Cars and radios bought on the installment plan were repossessed. The economy did not fully recover until World War II.

Impact of the Great Depression

Until the mid-1930s, no governmental agency kept data on unemployment, so there are no reliable statistics on the number of Californians out of work in the early 1930s. Estimates suggest that unemployment reached as high as 30 percent in San Francisco and Los Angeles by late 1932. The number of people employed in the oil industry was about three-fifths of what it had been in the mid-1920s. For lumbering and canning, it was about a third. The Bank of America compiled a monthly business index that, in late 1932, showed the state at 60 percent of normal. New construction slowed to a trickle. Department store sales declined by 38 percent between 1929 and 1932.

The Depression cruelly affected many Californians. In 1930, the Los Angeles Parent Teacher Association (PTA) launched a school milk and lunch program when teachers reported children coming to school hungry. Some LA schools remained open through the summer to dispense milk and lunch. Even so, in the fall of 1931, some children arrived at school so malnourished they were hospitalized. When the PTA ran out of funds, the county board of supervisors paid for the program. Aimée Semple McPherson’s church fed 40,000 people during 1932. On the San Francisco waterfront, Lois Jordan, the “White Angel,” fed as many as 2000 men each day using contributed food and financial donations. In 1931, the state created work camps for unemployed, homeless men. They worked on roads and built firebreaks and trails, but received no wages—only food, clothing, and a bed in a barracks. City and county governments mounted work programs in which unemployed men worked for a box of groceries. When San Francisco ran out of money for relief in 1932, a large majority of voters approved borrowing funds to provide minimal assistance to the unemployed.

In southern California, some claimed that Mexican immigrants were taking jobs away from whites or driving down wage levels. As unemployment rose, so did agitation to deport undocumented Mexicans, with the loudest voices coming from AFL unions, the Hearst press, and patriotic (and often nativist) groups such as the American Legion. During the presidential administration of Herbert Hoover (1929–1933), the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) conducted raids in Mexican neighborhoods. Thousands were deported to Mexico, the large majority for lacking proper papers, but the deportees included a significant number of American citizens, the American-born children of Mexican immigrants. The Los Angeles county supervisors offered county funds for transportation for Mexicans willing to return to Mexico, and more than 13,000 did so between 1931 and 1934. Other communities promoted similar programs. Those who were deported and those who returned on their own included some who had lived and worked in the United States for many years, and some left behind their homes, savings, and family members. After the election of Franklin D. Roosevelt (who took office in 1933), the INS took a more humane approach, and the number of deportations fell by half. In 2005, the California legislature approved a resolution apologizing for the violations of civil liberties and constitutional rights committed during the 1930s.

As unemployment rates rose, other ethnic groups also felt threatened. After the United States acquired the Philippine Islands in 1898, Filipino immigrants came to California, as growers sought workers for agriculture. Because the Philippines were an American possession, their residents were not considered aliens, but neither were they citizens. The 1940 census recorded more than 30,000 Filipinos in California, two-thirds of all Filipinos in the United States. Half worked in agriculture or canneries, and some led strikes during the early 1930s. Some white Californians urged that Filipinos be deported, but there was no legal basis for doing so. In 1930, anti-Filipino rioting broke out in Watsonville. Several Filipinos were injured, and two were killed. Other violence followed, spawned by fears that Filipinos were competing for jobs or by anxieties over Filipino men socializing with white women. Eventually, anti-Filipino attitudes combined with a long-standing promise of the Democratic Party to bring independence to the Philippines. In 1934, Congress passed and President Roosevelt signed the Tydings-McDuffie Act, which set in motion a process leading to Philippine independence. The same law cut migration from the Philippines to 50 people per year.

The plight of migrant farm labor drew less interest. As Mexican farm workers left or were deported, increasing numbers of Dust Bowl migrants took their place. Most Californians at the time thought of the migrants as refugees from drought, but many of them had been uprooted by technological change in agriculture (the transition from small farms to larger units that relied on heavy machinery) or by the impact of federal agricultural programs that favored landowners over tenant farmers. Usually denigrated as Okies, regardless of the state from which they came, they encountered miserable living conditions. The state Commission of Immigration and Housing, created in 1913 to supervise migratory labor camps, had its budget cut so much that, by 1933, there were only four camp inspectors for the entire state. Most migratory labor camps lacked rudimentary sanitation, and most migratory labor families could not afford proper diets or health care. A survey of migratory children in the San Joaquin Valley during 1936 and 1937 found that 80 percent had medical problems, most caused by malnutrition or poor hygiene.

Though some Californians reacted to rising unemployment by seeking scapegoats, others turned to a Marxist analysis and argued that the problem was with capitalism itself. The Socialist Party had declined since its high point before the war. Though it still provided a focal point for a critique of capitalism, it was able to muster less than four percent of the vote for governor in 1930, up from two percent in the 1928 election for the U.S. Senate.

In the 1930s, a different Marxist group began to attract attention. Radicals had formed the Communist Party (CP) of the United States shortly after the war, but it struggled through the 1920s, losing more members than it recruited. The CP defined itself as a revolutionary organization, devoted to ending capitalism and to uniting all workers. Communists saw the Soviet Union as the only workers’ government in the world and committed themselves to its defense. These revolutionary and pro-Soviet attitudes made it difficult to recruit American workers, few of whom wanted to overthrow the government or defend the Soviet Union. At the same time, CP organizers committed themselves to the “class struggle”—to helping workers achieve better wages and working conditions. They saw their special task as organizing the unskilled, African Americans, Mexican Americans, and other workers ignored by existing unions. Throughout the 1920s, they had little success. The California CP had 730 dues-paying members in early 1925, recruited 145 new members that year and in early 1926, but had only 438 dues-paying members in mid-1926—a loss of half their members in a year’s time.

In the early 1930s, the CP grew dramatically, in numbers and visibility. Communists organized protest organizations for the unemployed. Though the CP counted only about 500 members in the entire state in 1930, many more joined the party’s Unemployed Councils. In March 1930, the CP organized marches by the unemployed. One thousand people marched in San Francisco, where Mayor James Rolph met with them and offered them coffee. In LA, the mayor mobilized 1000 police to stand against the marchers and sent police to arrest leaders the night before the march. One LA police commissioner explained his view on dealing with radicals: “The more police beat them up and wreck their headquarters the better.” By early 1934, the CP counted 1,800 members in the state, and provided leadership to thousands more.

The Communists were not the only group from the fringes of the political spectrum to attract attention. On the right, remnants of the Ku Klux Klan were still active in some parts of California in the 1930s, and they found new allies in the Silver Shirts, a San Diego branch of a national fascist organization that emulated Nazism. Another right-wing, militaristic group, the California Cavaliers, organized statewide in 1935. These and similar groups usually blamed the state’s problems on Jews, immigrants (especially Mexicans and Filipinos), and Communists, and some added President Franklin D. Roosevelt and his New Deal. Most required their members to be proficient with firearms.

Some groups closer to the mainstream, notably the American Legion (the state’s largest organization of veterans), also mobilized against what its leaders saw as a Communist menace. Some Legionnaires joined vigilante groups to terrorize radicals and striking workers. The state organization set up a Radical Research Committee to collect information on suspected radicals, sometimes through undercover operatives. The committee cooperated closely with the Industrial Association and Associated Farmers (see p. 258) and traded information with local and state police and with military and naval intelligence. In Los Angeles, the Better America Federation denounced advocates of publicly owned utilities as Communists, tried to purge liberal books and magazines from the schools, and contributed to the repression of labor unions.

Labor Conflict

During the 1920s, labor organizations were on the defensive all across the country, and nowhere more than in California. The powerful Merchants and Manufacturers (M&M) in LA stood ready to block union efforts in southern California. In San Francisco, several failed strikes from 1919 to 1921 led to the decline of once-powerful unions. In 1921, the San Francisco Chamber of Commerce helped to organize the Industrial Association, with funding from banks, transportation companies, and utility companies—indeed, nearly every company in the city. From the early 1920s until the mid-1930s, the Industrial Association closely governed labor relations in San Francisco, blocking every effort to revive union organizations.

In the early 1930s, California agriculture was wracked by strikes, sometimes violent, usually in response to wage cuts or miserable working conditions. The first came in early 1930, in the Imperial Valley, when Mexican and Filipino farm laborers walked off their jobs in the lettuce fields. The strike spread to 5000 field workers. Communist organizers quickly offered help for the strikers through their union, which was soon renamed the Cannery and Agricultural Workers Industrial Union (CAWIU). Other strikes broke out elsewhere, most by Mexican and Filipino field and shed workers, and CAWIU organizers always appeared to offer support and seek converts. Whether in the Imperial Valley or Half Moon Bay, the CAWIU seemed unable to win strikes. By 1932, they had begun to target particular areas and to build an organizational base prior to a strike. In 1933, strike after strike hit the state’s agricultural regions. By August, more strikes were successful, pushing average agricultural wages from 16 cents an hour to 25 cents. Growers regrouped, however, and strikes in late 1933 were met by violence against the strikers and threats of lynching against the strike leaders.

Growers and business leaders formed the Associated Farmers in March 1934, with funding from the Industrial Association, banks, railroads, utilities, and other corporations. The Associated Farmers blamed Communists for the labor unrest in agriculture, launched a statewide anti-Communist campaign, and sought indictments of CAWIU leaders under criminal syndicalism laws. Seventeen CAWIU leaders, mostly CP members, were brought to trial in 1935. The Associated Farmers paid generously to assist the prosecution, and eight defendants were convicted. The CAWIU was dissolved the next year, but the Associated Farmers remained alert, ready to oppose any new efforts to unionize farm workers.

In May 1934, longshoremen (workers who load and unload ships) went on strike in all Pacific coast ports. Before World War I, Pacific coast longshoremen had been organized into the International Longshoremen’s Association (ILA). By the early 1920s, however, as a result of unsuccessful strikes, California dockworkers had no meaningful union. Dock work was harsh and dangerous, and longshoremen were hired through the “shape-up,” in which foremen hired men for a day at a time. In 1933, the ILA launched an organizing drive in Pacific coast ports. In San Francisco, Harry Bridges, an immigrant from Australia who had worked on the docks since 1922, emerged as a leader of one group of longshoremen including some CP members—who used the Waterfront Worker, a mimeographed newsletter, to advocate militant action.

In 1934, the ILA’s Pacific Coast District (California, Oregon, and Washington) sought a union contract. When waterfront employers refused, some 10,000–15,000 longshoremen from northern Washington to San Diego walked

Harry Bridges and other labor leaders meet in Washington D.C. in 1937 to plan a coordinated unionization drive among longshore workers. Following the meeting, John Lewis, the head of the C.I.O. vowed to support creating a "uniform policy for the entire industry."

out in an attempt to shut down shipping on the Pacific coast. They demanded a union hiring hall (replacing the hated shape-up), higher wages, and shorter hours. Greeted by picket lines upon entering Pacific coast ports, ships’ crews quickly went on strike with issues of their own, adding 6000 more strikers. In San Pedro on May 15, private guards fired on strikers, killing two of them.

The strike focused on San Francisco, site of the largest ILA local and of many employers’ headquarters. Bridges, chairman of the strike committee for the San Francisco local, became a prominent figure in opposing compromise and insisting on the union’s full demands. In late June, the Industrial Association took over the employers’ side of the strike and determined to reopen the port using strikebreakers under heavy police protection. Union members and their supporters fought back. During a daylong battle on July 5, police killed two union members and injured hundreds more. Governor Frank Merriam dispatched the National Guard in full battle array, armed with machine guns and tanks, to patrol the San Francisco waterfront. Ostensibly deployed to prevent further violence, the Guardsmen also protected the strikebreakers.

On July 9, thousands of silent strikers and strike supporters took over Market Street, solemnly filling that great thoroughfare as they marched after the caskets of those killed on July 5. From July 16 through July 19, the San Francisco Labor Council coordinated a general strike that shut down the city in sympathy with the striking maritime workers and, implicitly, in opposition to the tactics of the police and the governor’s use of the National Guard. Never before or since have American unions shut down a city as large as SanFrancisco through a general strike. At the time, business leaders and politicians feared that the general strike held the seeds of Communist insurrection, but the real moving force was workers’ anger over the use of government power to kill workers and protect strikebreakers. By late July, all sides agreed to arbitration, and the longshoremen secured nearly all of their demands.

The strikes by agricultural workers and by longshoremen and seafaring workers were the leading California instances of a strike wave that broke over the nation between 1933 and 1937. In 1933, Congress tried to reverse the economic collapse of the nation with the National Industrial Recovery Act. One of its provisions, Section 7-a, encouraged collective bargaining between employers and unions. Section 7-a stimulated union organizing all across the country, as workers turned to unions to stop wage cuts and improve working conditions. Everywhere, workers formed unions. In San Francisco, the number of union members doubled within a few years after 1933. In 1935, Congress passed the Wagner Labor Relations Act, strengthening and extending federal protection of unions and bargaining.

In Los Angeles, unions challenged the M&M, organizing in many fields, notably furniture making, printing, the movie studios, and construction. The M&M did not give in easily. They hired an army of private guards to protect strikebreakers and counted on close cooperation from city police, but they lost a showdown with the Teamsters’ Union in 1937. By 1941, unions claimed half the workers in LA as union members.

As union membership burgeoned, the labor movement divided between two groups: the American Federation of Labor (AFL), oriented to organizing the more skilled workers into unions defined along the lines of skill or craft; and a group led by John L. Lewis of the United Mine Workers, who called for an industrial approach to organizing, in which all workers in an industry would belong to the same union regardless of skill or craft. At first they called themselves the Committee on Industrial Organization (CIO) and worked within the AFL, but in 1937 the AFL expelled the CIO unions.

Lewis and the CIO reorganized themselves into the Congress of Industrial Organizations. The Pacific Coast District of the ILA, now led by Harry Bridges, broke away from the ILA to become the International Longshoremen’s and Warehousemen’s Union of the CIO. The CIO also chartered the United Cannery, Agricultural, Packing, and Allied Workers of America (UCAPAWA), which launched an organizing drive among California agricultural and cannery workers, only to meet strong and often violent opposition from the Associated Farmers. Nonetheless, UCAPAWA organized thousands of cannery workers, the large majority of them women, including many Mexicans. Latinas advanced to leadership in some UCAPAWA locals, and Luisa Moreno, a well-educated immigrant from Guatemala, became a vice president of UCAPAWA, the first Latina to serve in such a post in any American union. Other CIO unions, especially the Auto Workers, Steelworkers, Clothing Workers, and Rubber Workers, organized manufacturing workers, especially in southern California. AFL unions grew too, especially the Teamsters and the Machinists. By 1940, AFL unions in California claimed a half million members and the CIO had 150,000, making California a leading state for union membership.

Federal Politics: The Impact of the New Deal

The revolution in labor relations represents only one of the many ways that new federal policies changed life in California during the 1930s. There were many others. The political changes of the 1930s worked a transformation not just in state–federal relations but also in the relationship between individuals and the government at all levels. The impetus for most of these changes was the Depression. The first changes came during the presidency of Herbert Hoover, but greater changes came after 1933, under President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Hoover spent much of his four years as president addressing the Depression. He approved programs that went further in establishing state–federal cooperation than ever before. One example was the Hoover-Young Commission to plan the San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge. Another was his approval of funding for the bridge construction from the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC), an agency that loaned funds to companies to stabilize the economy. In the case of the Bay Bridge, the loan was to a state agency, for the purpose of constructing a publicly owned bridge—something unprecedented. As in the case of the dam project at Boulder Canyon, Hoover’s approval helped to promote other massive federal water projects throughout the West; however, Hoover was adamant that the federal government should not directly assist the unemployed or those in need.

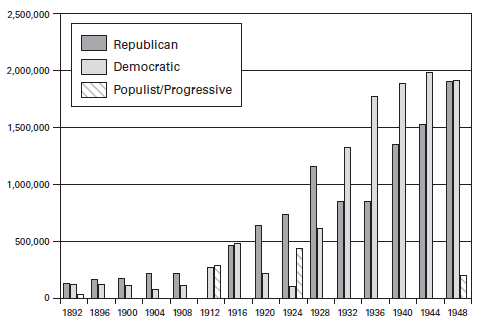

When Hoover faced reelection in 1932, he lost in a landslide to the Democratic candidate, Franklin D. Roosevelt, the governor of New York, who promised to do more to address the problems of the Depression. California’s voters gave 1,324,000 votes to Roosevelt, and 848,000 to Hoover. As Figure \(8.2\) on the next page indicates, the election marked the beginning of a new pattern to Californians’ voting for president, a move toward the Democratic Party.

As president, Roosevelt conveyed a confidence that something could be done about the Depression, and he called upon Congress to pass legislation for relief, recovery, and reform. The Public Works Administration (PWA) set up an ambitious federal construction program to stimulate the economy. In California, PWA paid for many new federal buildings—post offices, court buildings, and buildings on military posts and naval bases—and also new ships for the navy. Other PWA projects included schools, courthouses, dams, auditoriums, and sewage treatment plants. The Works Progress Administration (WPA),

Figure \(8.2\) Number of Votes Recieved by Major Party Presidential Candidates in California, 1892-1948

created in 1935, was a work program for the unemployed. WPA projects across the state included public parks, buildings, bridges, and roads. The WPA and PWA together helped to fund the Pasadena Freeway. All in all, the PWA and WPA had a major impact on the state’s infrastructure, but the WPA went beyond construction projects to include orchestras (composed of unemployed musicians), murals in public buildings (painted by unemployed artists), a collection of guidebooks (compiled by unemployed writers), and adult education programs (presented by unemployed teachers).

New federal agencies took up the plight of migratory farm workers. In 1935, the Resettlement Administration (RA) set out to construct camps with adequate sanitation and housing that met minimal standards. Two camps were built before the RA gave way, in 1937, to the Farm Security Administration (FSA), which continued the work of building and operating camps—13 by 1941. The FSA was closed down in 1942, however, ending direct federal efforts to assist migratory farm workers and their families.

The New Deal brought important changes to the governance of Indian reservations. Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, California was home to nearly 20,000 Native Americans, putting California among the half-dozen states with the largest Indian populations. In the early 1920s, whites and California Indians formed the Mission Indian Federation to improve the situation of southern California Indians. Similar efforts took place in the north. When the state legislature, in 1921, approved a law specifying that Native American children could only attend local public schools if there were no Indian school within three miles of their homes, Alice Piper, a Native American, sued to attend her local public school. In Piper v. Big Pine School District (1924), the California Supreme Court ruled in Piper’s favor. The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) also continued to buy small plots of land to create reservations for landless California Indians. Roosevelt appointed John Collier as the commissioner of Indian Affairs. A longtime critic of previous federal Indian policies, Collier closed down programs aimed at forced assimilation, including boarding schools and the suppression of traditional religious practices. His “Indian New Deal” included, as its centerpiece, the Indian Reorganization Act (1934), which encouraged tribal self-government.

State Politics: The Rise of the Democrats

Though California’s voters clearly turned to the Democrats in the 1932 presidential election and continued to vote for Democrats through the presidential elections of the 1940s, they showed more ambivalence in state elections. There was an increase in support for Democratic candidates, but that increase did not automatically translate to the election of Democrats to state offices.

In the elections of 1930, the real contest, once again, was in the Republican primary. The incumbent progressive governor, C. C. Young, faced two opponents in the Republican primary. One was James C. “Sunny Jim” Rolph, the popular mayor of San Francisco, first elected in 1911 and reelected every four years, usually by large margins. Though Rolph had promoted progressive causes in the 1910s, he became more moderate during the 1920s, and was probably best known, in 1930, for his outspoken opposition to prohibition. Young’s other opponent was Buron Fitts, a conservative from LA who was a staunch prohibitionist. Young, too, supported prohibition. Fitts and Young divided the “dry” vote. Rolph took the “wet” vote, won the Republican nomination, and easily defeated his Democratic opponent.

As governor, Rolph spent much of the state’s budget surplus on assistance to the victims of the Depression. He also supported the Central Valley Project Act of 1933 to create dams and canals for hydroelectric power and irrigation, and the bill passed despite strong opposition from electrical power companies. With Rolph’s support, the legislature repealed the enforcement of prohibition, which meant that policing the unpopular law was entirely the responsibility of a handful of federal officials. However, Rolph seemed to condone violence against farm strikers, and he publicly approved of the lynching, in San José, of two men suspected of kidnapping and murder. He died in office, in June 1934, and was succeeded by his lieutenant governor, Frank Merriam.

Democrats hoped to win the governor’s office in 1934, for the first time in more than 40 years. Voter registrations had shifted from the huge Republican majorities of the late 1920s to a fairly even split by 1934. In 1932, a Democrat captured one of California’s U.S. Senate seats. For 1934, Democratic Party leaders backed George Creel, a moderate liberal, for governor; however, the Democratic primary for governor became a battle between Creel and Upton Sinclair. Sinclair had become nationally famous for his novel, The Jungle, in 1906. A classic example of progressive muckraking, The Jungle revealed in sickening detail the unsanitary conditions and exploitation of workers in Chicago’s meatpacking industry. A Pasadena resident after 1915, Sinclair continued to write novels with strong social and political messages. He ran for governor as a Socialist in the 1920s, but changed his party registration to Democrat in 1934 and entered the Democratic primary for governor.

Sinclair’s slogan was “End Poverty in California,” soon abbreviated to EPIC. He wrote a novel—I, Candidate for Governor and How I Ended Poverty—and used it to promote his candidacy. At the center of the EPIC program was “production for use,” a plan to let the unemployed raise crops on idle farmland and make goods in idle factories, and then exchange their products using state scrip (by scrip, Sinclair meant state-issued certificates that would specify the value of the agricultural and manufacturing products). Thousands of Californians joined EPIC clubs across the state, making them a new force in politics. Sinclair won the Democratic nomination for governor by a clear majority, and his supporters won nominations for other offices. Frank Merriam, the bland conservative who had become governor upon the death of Rolph, won the Republican primary.

In the general election, Sinclair’s opponents attacked EPIC as unworkable and Sinclair as incompetent for proposing it. Sinclair’s plan reflected a weak grasp of economics but hardly deserved the abuse heaped on it as dangerously “red.” In fact, Socialists and Communists both vigorously attacked EPIC. Hollywood studios regularly produced a short news feature that ran in theaters before the main feature; now they created alleged news stories, actually staged, that claimed the state faced a deluge of hobos and Communists attracted by EPIC. Republicans hired press agents Clem Whitaker and Leone Baxter tosort through Sinclair’s writings and produce lurid campaign advertisements based on Sinclair’s supposed support for free love and contempt for organized religion. In the process, Whitaker and Baxter created a new career—that of the freelance campaign consultant—and their success inspired a host of imitators on both the right and the left. National Democratic leaders abandoned Sinclair, and Roosevelt refused to endorse him. Merriam won, but Sinclair had transformed the California Democratic Party, as 26 EPIC candidates were elected to the state assembly, including Augustus Hawkins, the first black Democrat to serve in the legislature. In many places, EPIC clubs began to prepare for the next election.

In the 1934 elections, the Communist Party showed surprising strength. Though their candidate for governor got fewer than 6,000 votes, Anita Whitney, the CP candidate for controller, got 100,000 votes and five percent of the total. Leo Gallagher, running for the supreme court without a party label but with support from the CP, received 240,000 votes and 17 percent. The CP was highly critical of the New Deal in 1933 and 1934, but from 1937 to 1939, top CP leaders reversed their position and encouraged party members to support New Deal Democrats.

EPIC was not the only unusual proposal to percolate out of southern California. In 1934, Francis Townsend, a retired physician from Long Beach, launched Old Age Revolving Pensions. He proposed taxing business transactions to pay $200 each month to every citizen over the age of 60 (except criminals) on the condition that he or she retire and spend the full amount each month. The plan had something for nearly everyone: older people could retire; putting money into circulation would stimulate the economy; and retirements would open jobs for younger people. It was enormously popular. Some older people bought goods on credit, expecting to pay for them with their first checks. Townsend’s popularity translated to political clout—California candidates hesitated to criticize his plan, and many endorsed it. The adoption of Social Security in 1935, however, took the wind from Townsend’s sails. In 1938, grassroots activists put a new panacea on the ballot, nicknamed “Ham and Eggs,” which proposed to pay $30 in state “warrants” every Thursday to all unemployed people over 50. The measure lost in 1938, and a revised version lost in 1939.

The progressive reforms that reduced the power of political parties may have made Californians more likely than before to cross party lines. Thus, they supported Roosevelt in 1932 and elected a Democrat to the U.S. Senate, but in 1934 they elected a conservative Republican as governor. In 1934, Roosevelt endorsed Republican Hiram Johnson for the U.S. Senate, and Johnson used cross-filing to win both the Democratic and Republican nominations. Like other prominent progressive Republicans, Johnson supported Roosevelt in 1932 and endorsed much of the early New Deal, but he was privately turning against Roosevelt by 1936. In 1936, California voters gave Roosevelt a large majority and elected a majority of Democrats to the state assembly for the first time in the 20th century. State senate districts, however, had been drawn to minimize the number of senators from urban districts, where the Democrats were developing much of their support.

After Merriam was elected governor in 1934, he disappointed his most conservative supporters by acting pragmatically to implement some New- Deal-type reforms, to create a state income tax (generally considered a liberal approach to taxation), and to increase taxes on banks and corporations. Seeking reelection in 1938, he faced Culbert Olson, a Democrat who had entered politics through EPIC and now campaigned to “Bring the New Deal to California.” In the Democratic primary, another former EPIC supporter, Sheridan Downey, won the nomination for the U.S. Senate, and still another former EPIC activist won the Democratic nomination for lieutenant governor. Business and conservative groups promoted Proposition 1, an initiative to clamp severe restrictions on unions, and they backed it with the most money spent to support a proposition up to that time. The Republican candidates for governor and senator supported Proposition 1. Despite the bitterness between the AFL and CIO, nearly all the state’s unions combined to defeat Proposition 1 and support the Democrats. Olson, Downey, and other Democrats won, and the Democrats again won a majority in the state assembly.

A good campaigner, Olson proved less effective as governor. He freed Tom Mooney and Warren Billings (see p. 231), for which he won high praise from labor and the left, but earned the hatred of conservatives. He also supported efforts to unionize farm workers. In 1939, Olson proposed a long list of reform legislation—including medical insurance for most working Californians and the protection of civil rights—but such proposals garnered no support among the conservative Republicans who dominated the state senate. In 1940, two years into the Olson administration, voters sent a majority of Republicans to the assembly. That same year, Hiram Johnson again won both the Democratic and Republican nominations for U.S. Senate through cross-filing, although, by then, he had become highly critical of the New Deal.

Cultural Expression During the Depression Decade

During the 1920s, many American writers and artists rejected the consumeroriented society around them. Their novels often seemed exercises in hedonism or escapism. Some artists produced works so abstract that they held different meanings for each viewer. In the 1930s, much of that changed. Some leading novelists of the 1930s portrayed working people and their problems, and others looked for inspiration to leading figures in American history. Artists produced realistic scenes, sometimes motivated by a desire for social change and other times rooted in affection for traditional values. And Californians produced some of the leading examples of these trends.

John Steinbeck defined the social protest novel of the 1930s. Born in Salinas in 1902, Steinbeck attended Stanford briefly. Among his early works, Tortilla Flat (1933) portrayed Mexican Californians and In Dubious Battle (1936) presented an apple-pickers’ strike through the eyes of an idealistic young Communist. The Grapes of Wrath (1939), which won the Pulitzer Prize for best novel, presented the story of the Joad family, who lost their farm in Oklahoma and migrated to California. There, the family disintegrated under the stresses of transient agricultural work and the violence of a farmworkers’ strike. Sinclair’s novel has been likened to Uncle Tom’s Cabin for its social impact. Some artists also presented social criticism in their work. Diego Rivera, the great Mexican muralist whose work usually carried a leftist political message, painted murals in California and influenced a generation of California mural painters. Other muralists, especially those in the WPA arts projects, often presented the lives of ordinary Californians or themes from the state’s history.

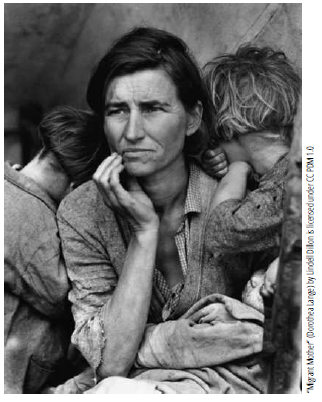

Dorothea Lange gave this photograph the title "Destitute peapickers in California; a 32 year old mother of seven children. February 1936." In 1960, in an article in Popular Photography, Lange explained how she took her famous picture: "I saw and approached the hungry and desperate mother, as if drawn by a magnet.... She said that they had been living on frozen vegetables from the surrounding fields, and birds that the children killed. She had just sold the tires from her car to buy food."

Dorothea Lange, a commercial photographer before the Depression, began photographing the victims of the Depression in the early 1930s. Lange became well practiced in photographing these victims, ranging from unemployed men in San Francisco to strikers and migrant workers. In 1935, the California Rural Rehabilitation Administration hired Lange and Paul Taylor (an economics professor at the University of California, Berkeley) to document the plight of agricultural labor, and she continued that work with the Federal Resettlement Administration. Her photograph of a farm-migrant mother and children, later entitled “Migrant Mother,” taken in 1936, emerged as perhaps the most famous and most moving photograph of the era. In 1939, Lange and Taylor published American Exodus, a documentary counterpart to The Grapes of Wrath, vividly depicting the misery of life in the migratory labor camps and in the fields, through photographs, commentary, and statistics.

Hollywood produced a few films of social criticism during this time, most notably an adaptation of The Grapes of Wrath (1940), starring Henry Fonda. Charlie Chaplin’s leftist politics were apparent in two important works: Modern Times (1936), portraying the dehumanizing tendencies of technology, and The Great Dictator (1940), which mocked Adolf Hitler. Studio heads were often uncomfortable with social protest films, however, and some barred them entirely, insisting that the public needed entertainment that would take their minds off the Depression. Musical extravaganzas like Forty-Second Street (1933) fit the bill. So did some westerns and gangster films, but others probed more deeply into the human condition. Stagecoach (1939), directed by John Ford, so defined the western genre that it inspired imitators for years after. Gangster films rose to popularity with Little Caesar (1930), which boosted Edward G. Robinson to stardom. Similarly, Hollywood turned the hardboiled detective stories of California writers Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler into immensely successful movies, notably The Thin Man (1934) and The Maltese Falcon (1941), both based on novels by Hammett. In The Maltese Falcon, set in San Francisco, Humphrey Bogart first defined the character he continued to develop in such later films as Casablanca (1942), The Big Sleep (1946), and Key Largo (1948).

By the late 1930s, the rise to power of Adolf Hitler in Germany and his Nazi party’s attacks on Jews and the Left produced a flood of refugees, and 10,000 of them came to southern California. Hollywood had attracted European immigrants from the beginning. Many of the studio heads and leading directors had been born in Europe, and many studio heads were Jewish. By the late 1930s, southern California had become home to a significant number of displaced European intellectuals, including the German novelist Thomas Mann, the Russian composer Igor Stravinsky, the German writer Bertolt Brecht, and the Austrian director Otto Preminger. Their presence gave the LA basin a more cosmopolitan cultural bent.

Many of these currents came together in 1939 and 1940, when San Francisco hosted the Golden Gate International Exposition, held on Treasure Island, a 400-acre artificial island created in San Francisco Bay with WPA funding. The island was connected to both sides of the bay by the new San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge, and had full views of the new Golden Gate Bridge. Much of the exposition’s architecture reflected prevailing Art Deco and Moderne styles, but sometimes with Pacific themes. One theme of the exposition was the unity of the Pacific basin, and one of the popular exhibits was the real lifearrival and departure of PanAmerican Airways’ Flying Clippers—giant (for the day) airplanes, able to carry 48 passengers that landed and took off from the water of the bay. PanAmerican charged $360 (equivalent to more than $5,500 today) for a one-way ticket to Hawai‘i. Another, more mundane, goal of the exposition was to promote the growth of tourism to the Bay Area.

California on the Eve of War

Treasure Island had been constructed with the intent that, after the exposition, it would become San Francisco’s airport. But the first year of the exposition was marked by war. War was already raging in Asia, as Japan had seized Manchuria in 1931 and then initiated all-out war against China in 1937. In 1939, Germany marched into Czechoslovakia, then Poland. Britain and France declared war on Germany. In 1940, German armies rolled into Denmark, Norway, the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, and France. When the Treasure Island exposition closed, the island became a base for the U.S. Navy.

The creation of a naval base on Treasure Island was just one of many examples of increased federal expenditures in California for the army and navy after World War I. In 1921, the U.S. Navy decided to divide its fleet into Atlantic and Pacific divisions. This decision was due partly to rising concerns about the intentions of Japan in the Pacific and the need to protect the American possessions there. San Francisco, Los Angeles, and San Diego all insisted that they were the best location for a navy base, which was predicted to have as many as 45,000 naval personnel. Members of California’s congressional delegation contested with each other over the prize, but in the end the navy decentralized its facilities, scattering elements up and down the Pacific coast. As international tensions increased in the late 1930s, so too did naval and military expenditures in California.

Despite the headlines of war, despite increasing naval and military preparations all around them, most Californians hoped to stay out of the war. Unlike 1914 through 1917, when advocates of preparedness often hoped openly that the United States would enter the war, few made such arguments from 1939 through 1941. All Californians were shocked when their radios announced, on Sunday morning, December 7, 1941, that Japanese planes and ships had attacked the American naval base at Pearl Harbor, Hawai‘i. California was on the verge of one of its greatest transformations.