7.2: Social and Economic Change in the Progressive Era

- Page ID

- 126976

While reformers struggled with conservatives over control of state government, the state’s social and economic patterns were undergoing important changes. Though not as obvious as the dramatic political battles between the reformers and defenders of the SP, these changes were no less important. And many of them worked their way into the political process.

Immigration and Ethnic Relations

Between 1900 and 1910, California’s population grew more rapidly than at any time since the Gold Rush. The growth was most pronounced in southern California and the San Joaquin Valley. In 1900, California’s population ranked 21st among the 45 states. By 1920, it moved up to eighth among 48.

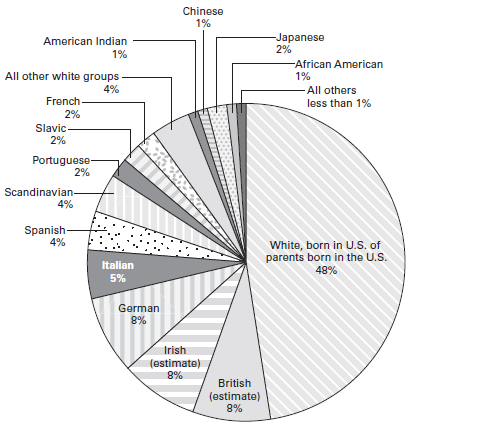

The state’s population was becoming racially more homogeneous. In the 1850s, a quarter or more of all Californians were African American, American Indian, Asian, or Latino; however, due to white migration from other countries and from other parts of the United States, the state became 95 percent white by 1910. Among white Californians during these years, nearly half were immigrants or children of immigrants, and these foreign-stock Californians came from many different cultural backgrounds. The 1920 census recorded the language of first- and second-generation white immigrants, and those data provide an approximation of their cultural backgrounds. Figure 7.1 indicates the ethnicity, based on language or race, of Californians in 1920. (In Figure \(7.1\), the percentage for British and Irish are estimated because the census data combined those two groups. Those listed as speaking Spanish include those whose parents were born in Latin America, Spain, and elsewhere.)

Between 1900 and 1908, 55,000 Japanese immigrants came to the United States, and most settled in California. Earlier, a few Japanese students had studied at American universities, including Berkeley and Stanford. With the decline in the number of Chinese Californians after the 1880s, California growers sought new sources of labor, including Japan. Smaller numbers of immigrants from Korea and the Punjab area of India (mostly Sikhs) also came to California. And after the United States acquired the Philippines in 1898, Filipino migrants began to arrive.

Figure \(7.1\) Californians in 1920, by Race, Ethnicity, or Mother Tongue of Whites of Foreign Parentage

THis figure suggests the ethnic diversity of Californians, even at the same time that it indicates the lack of racial diversity. THough the population of the state was nearly 95 percent white, there was great diversity within the white population in terms of ethnicity. In this figure, the ethnicity of teh white population is based on the "mother tongue," i.e., the first language of those who were foreign-born or whose parents were foreign-born. Among the whites who were born in the U.S. of parents born in the U.S., many were also likely to have identified with one of the ethnic groups noted.

The Exclusion Act and its extensions significantly limited immigration from China, but those who could prove that they were born in the United States, or were born to American citizens, were citizens and had the right to enter the country. A brisk trade developed in providing appropriate evidence to would-be immigrants, who became known as “paper sons” or “paper daughters.” Sometimes called the “Ellis Island of the West,” the Immigration Station on Angel Island, in San Francisco Bay, was opened in 1910. Its major purpose was to detain and interrogate Chinese entering the country and to seek evidence of fraudulent papers. Most were detained for two to three weeks, some longer.

The rise in immigration from Japan provoked a revival of anti-Asian sentiments. San Francisco union leaders formed the Asiatic Exclusion League. In 1906, the city’s school board, dominated by the Union Labor Party, ordered students of Japanese parentage to attend the segregated Chinese school. Newspapers and politicians in Japan denounced the segregation order as a nationalinsult. Most Californians knew that Japanese forces had recently delivered a stunning defeat to Russia—a white, European nation—in the Russo-Japanese War. Anxious to maintain good relations with Japan, President Theodore Roosevelt persuaded the San Francisco school board to rescind the segregation order. In return, he promised to persuade the Japanese government to cut off the migration of laborers to the United States. This he accomplished through the “Gentlemen’s Agreement” (not a formal treaty) of 1907–1908. At the same time, Roosevelt sent the U.S. Navy around the world, painted white as a sign of peaceful intentions—and known therefore as the White Fleet. It was also, however, a strong statement of American ability to carry naval warfare into Japanese waters.

After 1908, immigration from Japan was reduced but not stopped. The large majority of those who arrived before 1908 were males, and many had their relatives in Japan arrange marriages for them. “Picture brides” were permitted to enter the United States until the early 1920s. Thus, the number of Japanese Californians increased from 41,356 in 1910 to 71,952 in 1920. Many made their living as farmers, working small plots—the average was 70 acres in 1920—where they raised labor-intensive crops such as vegetables or berries.

During the early years of the 20th century, many Mexicans migrated north, most to south Texas and southern California. Though this migration began before 1910, the numbers increased greatly as many Mexicans sought to escape the revolution and civil war that began in 1910—and the serious social and economic dislocations that devastated their nation for years afterward. At the same time, exclusion of Asian immigrants produced a growing demand for Mexican labor in California agriculture.

A large Mexican community developed in Los Angeles. Los Angeles County and surrounding areas included significant agricultural operations. Many Mexican immigrants worked as agricultural field workers or cannery workers, following the crops through the growing, harvesting, and canning seasons, then spending the winter in LA. There, they joined a long-standing Mexican community in which many men worked in railroad construction and maintenance (including LA streetcars), construction, or furniture making, and women worked in garment making—all of which, like agricultural field work and canning, were often seasonal in nature.

Other Mexican immigrants lived in small barrios along the coast or inland. In 1903, Japanese and Mexican sugar beet workers in Oxnard formed a union, conducted their meetings in both languages, went on strike, and won their major objectives. When they petitioned for a union charter from the American Federation of Labor (AFL), however, they were refused because their union admitted Asian workers, a violation of existing AFL rules.

Throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries, California continued as home to one of the largest American Indian populations in the nation. Yet California had few reservations, and they were small both in size and in number of residents. Most California Indians continued to live outside the reservations, as they had since the United States acquired California.

Congress, in 1905, authorized an investigation of conditions among California Indians. A special agent, C. E. Kelsey, traveled throughout the state, visiting almost every Indian settlement. He contacted 17,000 California Indians, of whom only 5,200 lived on reservations. Kelsey found that about 3,000 of the nonreservation California Indians owned land, most of which was worthless for farming. More than 1,000 lived in federal forest reserves and national parks, areas that had been their traditional homelands. Nearly 8,000 lived in rural areas, typically in rancherías where they preserved some traditional ways of life even as they adapted to white society. Men often worked as farm laborers, stock herders, lumber workers, or miners, and many women worked as laundresses, domestic servants, or basket makers. Those not living on reservations usually tried to avoid attention, as they could still be targets for random violence. Those on the reservations had more protection from random violence but were constantly pressured by agents of the Bureau of Indian Affairs to give up their traditional ways and send their children to boarding schools.

Kelsey’s report led Congress to appropriate funds to create reservations for the landless California Indians. As the Commissioner of Indian Affairs explained in 1906, by establishing new reservations, the Indians of California “will be protected from the aggression of white people and have a fair chance to make a living.” Federal authorities began to convert some rancherías into small, but official, reservations. Some 50 new reservations were eventually established, many of them based on existing rancherías. For example, the Pinoleville Reservation, comprising about 100 acres (less than a quarter of a square mile), was established in 1911 on land that a group of Pomo had purchased 30 years before. California’s older reservations were also experiencing change. At Round Valley, protests against the federally run school led in 1915 to the creation of a public school on the reservation, with control lodged in a school board elected by reservation residents.

Figure \(7.1\) illustrates the diversity of languages—and cultures—among Californians classified as white. In fact, the diversity was even greater, for the 49 percent of the population who were white and born in the United States of parents born in the United States included many descendants of immigrants who still identified with an ethnic group.

Immigration in the early 20th century expanded existing Italian communities, especially in the San Francisco Bay area, where earlier Italian immigrants had established themselves in viticulture, horticulture, and fishing. By the early 1920s, San Francisco had the sixth largest Italian community in the nation, and was second only to New York City, among major cities, in the proportion of its population of Italian parentage.

Other European groups who arrived in California in significant numbers after 1900 included Eastern European Jews, many of them fleeing persecution in Russia; Armenians, many fleeing persecution from the Turkish empire; and Portuguese, including many from Portugal’s island possessions in the Atlantic. Eastern European Jews tended to settle in urban areas, especially San Francisco and Los Angeles, which had established Jewish communities, mostly of German origin, dating to Gold Rush days. Many Armenians were drawn to farming in the San Joaquin Valley, especially in the area around Fresno.

From the 1870s through the early 20th century, some black leaders had promoted the creation of all-black communities as places where African Americans could exercise full political rights and enjoy full economic opportunities—rights and opportunities denied them in the South. Among these all-black communities was Allensworth, near Bakersfield in the southern San Joaquin Valley. This community was founded in 1908 by Allen Allensworth. Born into slavery, Allensworth spent a career as an army chaplain, reaching the rank of lieutenant colonel, and then retired to Los Angeles in 1906. His inspiration for an all-black town came from the California Eagle, a black newspaper, that advised African Americans: “Get a home of your own. Get some property.” He especially recruited members of the U.S. Army’s four all-black units, urging them to live in Allensworth after completing their military service. Allensworth voters elected Oscar Overr as the first African American justice of the peace since the time when California had become a part of the United States. Problems with the water supply contributed to a decline of the town in the 1930s.

Economic Changes

California’s economy remained both diverse and highly productive. The 1920 census reported that, during the previous year, the state’s farms and ranches had yielded produce worth $770 million, and its mines, quarries, and oil wells had produced $163 million worth of minerals. At the same time, California manufacturing enterprises produced nearly $2 billion worth of goods. (One dollar in 1920 is equivalent to nearly $11.00 now.) Based on the number of employees and the value of the products, food processing was the largest industry, followed by petroleum refining; other important manufacturing industries included metal products, lumber, printing, and clothing.

During the early 20th century, California agriculture continued to diversify through the expansion of specialty crops, especially fruit, nuts, grapes, and vegetables (Map \(7.1\) shows where agriculture crops were being produced as of 1909.). By 1920, California ranked first among the states in production of many crops, including well over half of all lemons, oranges, olives, apricots, nuts, plums, table grapes, and raisins. Citrus crops were concentrated in southern California, other fruits and nuts in the Santa Clara Valley and around San Francisco Bay, and grapes in the wine-growing region north and east of San Francisco Bay and in the raisin-producing region of the San Joaquin Valley.

Map \(7.1\) Value of All Crops, 1909

This map shows the distribution of California's agricultural crops, as of 1909. Note, even this late, that irrigation facilities in the Central Valley had still not developed to the point that it could challenge the Bay Area and LA basin as the most productive agricultural regions.

Expansion of fruit and vegetable growing spurred food processing. As early as 1900, California ranked first among the states in canning and preserving fruits and vegetables, producing a quarter of the nation’s canned and preserved fruits and vegetables in 1900 and half by 1919. The expansion of specialty crops and of canneries necessitated a significant labor force at harvest time, but there was often little work for such employees at other times of the year.

The emergence of large numbers of relatively small-scale fruit, nut, and vegetable growers prompted the development of growers’ organizations, initially to influence prices and assist distribution. Orange growers developed an effective marketing cooperative, renamed the California Fruit Growers’ Exchange in 1905. It became a powerful force in the industry, organizing nearly all aspects of marketing, and, in 1908, creating its own brand name, Sunkist, which it promoted through extensive advertising. Given this success, other specialty

crop growers created their own marketing cooperatives based on the orange growers’ model.

In 1900, gold remained the most important mineral product of California, exceeding in value all other mineral products combined. Petroleum was in second place, and California ranked fifth among the states in the value of refined petroleum products. By then, an oil boom was developing in southern California. Observers in 1899 noted that the only problem with California oil was that it was not well suited for refining into kerosene, then the chief product of refineries because of the demand for home lighting. California petroleum was better suited for making gasoline, for which, in 1899, there was less demand. That soon changed dramatically. By 1920, Californians had registered one car for every six residents, and petroleum production soared. By 1919, California stood second among the states in the making of refined petroleum products.

Earthquake and Fire in 1906

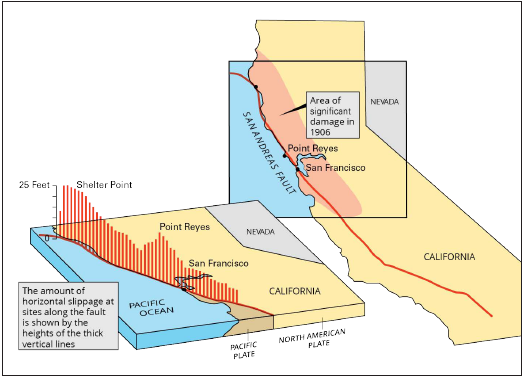

In 1906, nearly half of all Californians lived around San Francisco Bay or along the coast between Monterey and Eureka. Nearly all of them were jolted awake a few minutes after five o’clock in the morning, on April 18, 1906, when a monstrous earthquake rumbled along 296 miles of the San Andreas Fault, from near San Juan Bautista to Cape Mendocino. Shaking was felt as far away as Los Angeles, Oregon, and Nevada. Seismologists now conclude that the most severe shaking centered on two locations, west of San Francisco and west of Bodega Bay. They now estimate the moment-magnitude (\(M_{w}\)) at 7.9—one of the two most powerful earthquakes in California’s recorded history. Map \(7.2\) shows the extent of the slippage.

The earthquake toppled centuries-old redwoods, destroyed farms and villages, set church bells ringing wildly, and caused brick walls and chimneys to crash to the ground. One witness in San Francisco said, “I could see it actually coming up Washington Street. The whole street was undulating. It was as if the waves of the ocean were coming toward me.” The earthquake destroyed thousands of buildings and killed hundreds of people. It twisted streets, sidewalks, and streetcar tracks, and broke water lines, gas pipes, and electrical power wires.

Map \(7.2\) Slippage Along the San Andreas Fault in 1906

These maps show the extent of the 1906 earthquake. The map in the upper right indicates the geographic range of damage, from near San Juan Bautista to Cape Mendocino, about 270 miles. The diagram in the lower left shows the amount of horizontal movement of the earth for various locations. Where was the most serious slippage? Why is this earthquake usually closely associated with San Francisco?

In San Francisco, broken water mains rendered fire hydrants useless. Fifty or more fires broke out, fed by escaping gas. For the next three days, city residents struggled to contain what became a firestorm. General Frederick Funston, commander of the U.S. Army at the Presidio, sent troops to keep order and fight the fires. Without water to battle the flames, firefighters and federal troops dynamited buildings to build firebreaks.

Earthquake, fire, and dynamite destroyed the heart of the city, 4.11 square miles and 28,000 buildings, including three-quarters of the homes of the city’s residents. Destruction was almost universal within the fire zone—mansions and tenements, churches and brothels, saloons and libraries. The official record listed about 500 deaths in San Francisco and 200 outside the city, but subsequent researchers concluded that the number probably reached 3000 or more. Financial help poured in from individuals, organizations, and governments— some $9 million, used for food, temporary housing, and assistance in reestablishing homes and businesses.

Californians rushed to rebuild. San Franciscans feared that any delay in reconstruction would endanger their place as economic leader of the West. Though a few civic leaders urged a careful, planned approach, including wide

Compare this photograph of San Francisco after the earthquake and fire of 1906 with the photograph on p. 178, taken about a year before this one. Among older buildings, the devastation was nearly complete. In the distance can be seen the city's first steel-frame office buildings, nearly all of which survived the earthquake, though they were also gutted by fire. Why did San Francisco business leaders rush to rebuild the city rather than engage in a carefully planned reconstruction?

boulevards and other civic amenities, in the end, the city was rebuilt much as before—although in the current architectural style.

Water Wars

The fire gave new urgency to civic leaders in both San Francisco and Los Angeles who were trying to create water projects. While the danger of fire provided a good talking point, the major concern in both cities was water for growth.

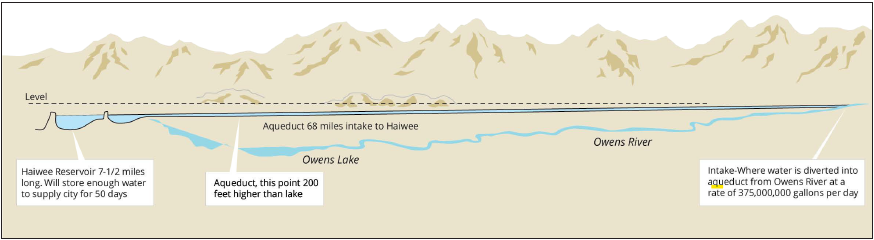

In the late 1890s and early years of the 20th century, civic leaders in Los Angeles secured their city’s control over the Los Angeles River. In 1903, voters approved a charter amendment creating a Board of Water Commissioners to oversee the city’s water and remove it from politics. Such commissions were one of the new forms of government that developed during the progressive era. By 1904, the Los Angeles River could not sustain future urban growth, so William Mulholland, superintendent of the LA water system, launched an

Map \(7.3\) THe Owns River Water Project

This project diverted nearly the entire flow of the Ownes River into an aqueduct that ran the length of the Owens Valley and emptied into the Haiwee Reservoir. From there, the water entered an aqueduct which carried it some 150 miles to the San Fernando Valley. Why was the acquisition of large amounts of water crucial to the growth of Los Angeles?

audacious plan. The city secretly bought up land, including water rights, along the Owens River, 235 miles north of LA. In 1907, city voters approved a bond issue for an aqueduct from the Owens Valley to the San Fernando Valley in Los Angeles County. Completed in 1913, the project diverted virtually the entire Owens River into the LA water system, providing four times as much water as the city needed and permitting rapid development in the San Fernando Valley, which was annexed to LA in 1915. Though some Owens Valley residents resisted the water project in court, LA won, and the Owens Valley became a parched area suitable mostly for cattle grazing. By 1920, Los Angeles expanded to nearly 365 square miles and half a million people.

In San Francisco, civic leaders also worried that the privately owned Spring Valley Water Company could not provide enough water for the growth of the city. Mayor James Phelan, in 1901, chose the Hetch Hetchy Valley for a reservoir. Located 170 miles east of San Francisco, the valley was a canyon with near-perpendicular granite walls—2,500 feet high—and a flat meadow floor, ideal for a reservoir if a dam were built across the canyon entrance. It was part of Yosemite National Park, but uses other than recreation were then permitted in national parks. In 1910, city voters approved bonds to construct a water system based on Hetch Hetchy. The city then sought permission from Congress to dam the valley. In addition to opposition from the Spring Valley Water Company, John Muir and the Sierra Club argued forcefully against construction in a national park. Hetch Hetchy, Muir proclaimed, was “one of the greatest of all our natural resources for the uplifting joy and peace and health of the people.” “Dam Hetch Hetchy!” he exclaimed angrily. “As well dam for water-tanks the people’s cathedrals and churches, for no holier temple has ever been consecrated by the heart of man.” Electrical power companies, especiallyPacific Gas & Electric, also opposed the project because the dam would generate electricity and might lead to public ownership of the city’s electrical system. Despite this opposition, Congress passed, and President Woodrow Wilson signed, the necessary legislation in 1913, and construction began in 1914. Hetch Hetchy water finally flowed through the city’s faucets in 1934.

The struggle over Hetch Hetchy revealed divisions within the emerging environmental movement. On one side were those like Muir, who argued for the preservation of wilderness as a place where urban people might find inspiration and recreation. On the other side were progressives like Phelan and Gifford Pinchot, Theodore Roosevelt’s chief adviser on conservation, who defined conservation as the careful management of natural resources so as to secure the maximum benefit from them, and who argued that the needs of a half million thirsty San Franciscans should take precedence over the recreation of a few “nature lovers.” The preservationists lost the battle but helped to shape the nation’s awareness of the long-term need to preserve national parks.

As San Francisco, Los Angeles, and other cities began to tap the water of the Sierra Nevada for their own uses, California farmers were also expanding their irrigation facilities. By 1920, more than half of California’s farms were irrigated. Some irrigation could be found in almost every county but was most common in the San Joaquin and Imperial Valleys and the citrus-growing areas of Los Angeles and Orange Counties.

Individual entrepreneurs developed many of the initial irrigation projects in California; however, the National Irrigation Association, created in 1899, set out to secure federal financing of irrigation projects. Francis Newlands, a member of Congress from Nevada and the son-in-law of William Sharon (p. 171), introduced key legislation. The National Reclamation Act of 1902, also called the Newlands Act, reserved the funds from the sale of federal lands in 16 western states for irrigation projects. To promote family farms, the law specified that only farms of 160 acres or fewer could receive water from its projects. The Newlands Act established a new federal commitment, later expanded many times: The federal government would assume responsibility for constructing western dams, canals, and other facilities that made agriculture possible in areas of slight rainfall. Over the course of the 20th century, governmental water projects profoundly transformed the western landscape, and water—perhaps the single most important resource in the arid West— came to be extensively managed.

California in the World Economy

The growth in agriculture, manufacturing, and petroleum refining were all reflected in the cargo of the ships that left California’s ports, and the importance of those ports was magnified by construction of the Panama Canal. Californians eagerly anticipated the completion of the canal, expecting that it would boost the volume of cargo moving through their ports and significantly reduce the cost of shipping between the West Coast and the East. In both San Francisco and Los Angeles, harbor commissions rushed port improvements to completion.

San Francisco hosted an international exposition to celebrate the opening of the canal. Dominated by a dazzling “Tower of Jewels,” the Panama-Pacific International Exposition opened in 1915. Though the exposition presented exhibition halls that displayed the commercial and cultural products of much of the world, San Francisco civic leaders had another purpose as well—they hoped the exposition would provide clear proof of the city’s recovery from the devastation of 1906. A similar exposition celebrating the opening of the canal was held in San Diego, and some of its structures, later restored, now stand in Balboa Park.

The opening of the canal in 1914 did significantly increase intercoastal shipping. By the early 1920s, the port of San Francisco was unloading half a million tons of cargo a year from the eastern United States, with metal products and coal the most prominent. Almost as much cargo bound for the East Coast passed over the San Francisco docks, led by canned goods. California’s agricultural produce was also shipped all around the Pacific and to Great Britain and Europe, and refined petroleum products were exported throughout the Pacific. California’s ports also handled a large volume of Pacific imports— Hawaiian pineapple and sugar, coffee and crude oil from Latin America, silk from Japan and China, as well as coconut products (used in making soap and other toiletries) and sugar from the Philippines and the Pacific islands. California also imported iron, steel, and coal from Great Britain and Europe.