5.4: New Social and Cultural Patterns

- Page ID

- 126966

During the 20 years following the discovery of gold, the state was transformed in many ways beyond the economic changes. California acquired new social institutions, especially educational and humanitarian institutions, and developed a reputation as a literary center.

Gender Roles and New Social Institutions

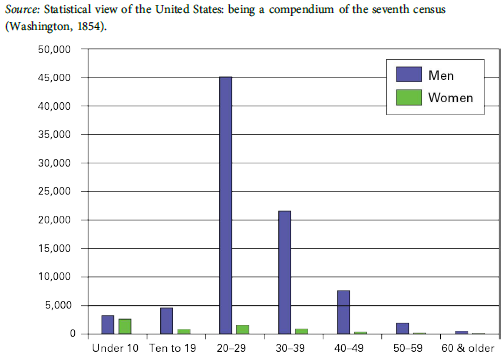

The thousands of gold seekers gave the population of the new state a peculiar composition—the state’s population in 1850 was composed overwhelmingly of young men. As seen in Figure 5.1, more than half the population was male and aged between 15 and 30. But the imbalance between men and women persisted

Figure \(5.1\) Numbers of Men and Women by Age, 1850

This figure vividly shows the extreme demographic disproportions by age and sex that were created by the Gold Rush. What do these data suggest regarding the nature of life in the mines?

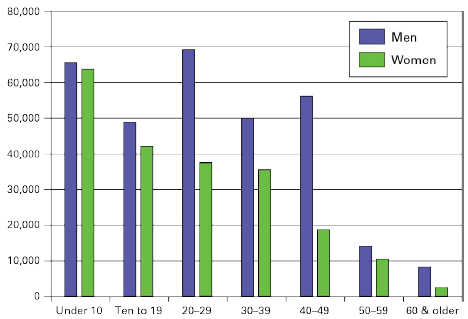

Figure \(5.2\) Numbers of Men and Women by Age, 1870

Note how men continued to outnumber women long after the intial stages of the Gold Rush had passed. Such demographic disproportions are typical of frontier economies dependent on the exploitation of raw materials, for example, through mining, lumbering, or ranching. What does this suggest about the California economy?

after many gold seekers returned to their homes in the East or left for other mining regions. Figure \(5.2\) presents data for 1870, indicating a continuing, though not so extreme, disproportion between men and women aged 20 to 50. This ratio between men and women, characteristic of frontier societies, carried implications for other social patterns.

Many Americans in the mid-19th century had sharply defined expectations regarding social roles for men and women. Domesticity was the notion that the proper place for a woman was in the home as wife and mother, and that as wifemother she was guardian of the family, responsible for its moral, spiritual, and physical well-being. As moral guardians and protectors of children and families, women also assumed important roles in the church and the school and in voluntary organizations devoted to caring for women, children, and the less fortunate. Beyond this, moreover, many Americans believed that women ought not experience much of the world, for fear that business or politics, with their sometimes lax moral standards, might corrupt women. The best choice, it was widely argued, was for women to occupy a separate sphere, immune from such dangers. Though widely advocated in the pulpits and journals of the day, the concepts of domesticity and separate spheres proved most typical of white middle-class and upper-class women in towns and cities, and often held little relevance for farm women, working-class women, and women of color.

Many 19th-century Americans also accepted the notion that men naturally tended to be materialistic where women were spiritual and that men tended to be adventurous or even hedonistic where women were restrained and refined. “Nothing is better calculated to preserve a young man from contamination of low pleasures and pursuits,” stated one guidebook for young men, than frequent contact “with the more refined and virtuous of the other sex.” In California in the 1850s, however, the extreme imbalance between the numbers of men and women made such contact unlikely for many young men. Thus, few Americans were surprised that, without the restraining presence of women, the largely male mining camps seemed to be given over to adolescent-like excesses of vice, violence, and greed.

As women arrived in California during the 1850s and 1860s, many brought with them the middle-class expectations of their day, and they quickly set about constructing social institutions intended to convey morality, educate the young, and care for the unfortunate. They did not do so by themselves, of course, for many men also understood the value of such institutions. In 1850, there were only two public schools and seven teachers in the entire state. By 1870, Californians had created 1,342 public schools, taught by more than 2,400 teachers, of whom 1,400 were women. The 28 churches of 1850 expanded to 643 in 1870. Californians also organized other social institutions— orphanages, benevolent societies, libraries, reform associations—and many of them relied for their continuation on the voluntary labor of middleand upper-class women.

Not all women who migrated to California accepted the prevailing social definitions of domesticity and separate spheres. Some came to California to get rich, a few by panning for gold, more by selling meals and lodging to miners, and probably the largest number by prostitution. Others challenged prevailing gender roles in other ways. Ada Clare, a San Francisco journalist, urged women to take advantage of a new gymnasium and to build themselves up physically, to dispel the prevailing social view of women as frail and sickly. Laura de Force Gordon delivered the state’s first public lecture on woman suffrage in 1868 and helped to form a state woman suffrage association early in 1870. Another early proponent of woman suffrage was Emily Pitts Stevens, a former schoolteacher who launched the state’s first newspaper committed to women’s rights in 1869.

The Growth of Religious Toleration

California in the 1850s was rife with ethnic hostility and conflict, but it differed little in that regard from other parts of the nation. Discrimination against free African Americans and mistreatment of American Indians could be found nearly everywhere to the east. California and the West were unique, however, in the diversity of their ethnic groups. In the eastern part of the country, racial relations usually involved blacks and whites, or sometimes whites and Indians,

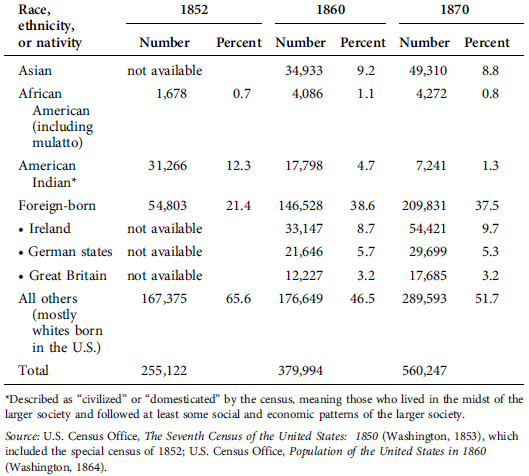

Table \(5.1\) Race, Ethnicity, or Nativity for California Population, 1852, 1860, 1870

or, rarely, blacks and Indians. Racial and ethnic relations in the West, however, involved not just American Indians and Americans of European and African descent, but also Mexican Americans (many of them mestizos) who had become citizens under the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, and immigrants from Asia, Europe, Australia, the islands of the Pacific, and Latin America. (Table 5.1 presents data on groups included in census tabulations for 1852, 1860, and 1870.)

The Gold Rush attracted many European immigrants, some of whom came from intermediary points including the eastern United States and Australia. The influx included groups subject to discrimination and hostility in the eastern United States. Irish immigrants, for example, were depicted in some eastern newspapers as whiskey-swilling ignoramuses. Anti-Catholicism was as old as the Reformation, and anti-Semitism was older. The Know-Nothing movement of the mid-1850s drew support all over the country by criticizing immigrants, especially Catholic immigrants.

Californians, particularly in the gold-mining areas, seem to have developed an unusual toleration of religious differences. One historian carefully surveyed all available records and found only two clear instances of anti-Semitic discrimination in the mining regions during the 1850s. In 1850, the California constitutional convention alternated its daily opening prayer between Protestant and Catholic clergymen. Students in the Catholic school in Los Angeles in 1859 included not just Catholics but also Protestants and Jews. A few years before, Protestants in San Francisco had contributed generously to help build a new Catholic church.

Despite the victory of the Know-Nothings in the state elections of 1855, a similar religious toleration seemed to characterize most of the new state’s politics. When he was active in New York Democratic politics, Broderick had understood that the state’s Democratic leaders were unwilling to permit Irish Catholics to rise too far. In California, Broderick won a seat in the U.S. Senate in 1857. The Irish-born and Catholic John Downey became governor in 1860 after being elected lieutenant governor the year before. San Franciscans elected an Irish Catholic mayor in 1867, and two Irish Catholics followed Broderick into the U.S. Senate from California before 1870. Catholic Californios were elected to local offices in some parts of northern California as well as in the south, and José Estudillo was elected state treasurer, serving from 1875 to 1880. Jews were also elected to local offices in the mining regions in the 1850s, and Solomon Heydenfeldt, who was Jewish, won election to the state supreme court in 1851.

One key to understanding this toleration of Catholics and Jews may be found in the Gold Rush, when respect went to those who prospered most. By 1870, San Francisco had 27 Irish bankers; at the same time, Philadelphia (much larger) had 18 and Boston (also much larger) had only four. Another part of the reason is undoubtedly the sheer numbers of Catholics—half the churchgoers in the state by one estimate in 1860. Recent historians suggest that the presence of significant numbers of African Americans, American Indians, Chinese, and mestizos may have led whites—whether Protestant, Catholic, or Jewish, Irish, German, British, Californio, or old-stock American—to focus on their “whiteness” rather than their religion or national origin. Whatever the reasons, by 1860 California was developing a reputation for religious toleration. That reputation, however, was limited to religion and failed to extend to race.

Chinese immigrants were barred from American citizenship. Congress approved the first federal law on naturalization in 1790 and, although amended occasionally, the law provided that only white immigrants might become naturalized citizens. State laws also discriminated against immigrants from China. In a court decision in 1854, the law that barred African Americans and American Indians from testifying in court against whites was extended to the Chinese. Though local school boards first created racially separate schools for black students, local officials soon mandated segregated schools for Chinese students as well. The state legislature in 1863 directed the state superintendent of instruction to withhold funds from school districts that did not create separate schools for “Negroes, Mongolians, and Indians.”

Writing the Gold Rush

Among those who came to California in the 1850s and 1860s were young writers, some of whom created new patterns in American literature. Life in the mining districts stimulated the creative imagination of some who mined the excitement and turbulence there for a wealth of literary plots. Writers published articles, poems, essays, and short stories in the new newspapers and literary journals. By the late 1850s, San Francisco could choose among more than 10 daily newspapers and a larger number of weekly or monthly publications. Every mining town had at least one local paper, and often two. Among the many firsthand accounts of the Gold Rush that appeared in such publications, perhaps the finest were the 23 letters written by Louise Clappe under the pseudonym Dame Shirley and published in the San Francisco Pioneer in 1854 and 1855.

Bret Harte arrived in California in 1854 and tramped through the mining country before taking a newspaper job in Humboldt County. He scathingly condemned local ruffians for the brutal slaughter of 60 Indians, mostly women and children, then fled when he was apparently threatened with lynching. He made his way to San Francisco and soon became editor of the Overland Monthly. In its pages, he presented accounts of life in the diggings, drawing both on his own experience and on other firsthand accounts. Through stories such as “The Outcasts of Poker Flat,” Harte contributed significantly to the development of local color and realism in American fiction. Other California journalists also began to develop similar themes.

The most famous and influential of the Gold Rush authors was Samuel L. Clemens, a Mississippi River steamboat captain who fled from the strife of the Civil War and arrived in Nevada Territory in 1861. There he mined, speculated in mining stock, camped through the Sierra Nevada, and began to write humorous essays for the Virginia City newspaper. He began to use the pen name Mark Twain and quickly became the most popular humorist in Nevada. In May 1864, he moved to San Francisco, where he developed his humor into satire. His short story “The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County” was published in a New York journal in 1865. A San Francisco newspaper, the Alta California, commissioned him to travel to the Mediterranean and the Holy Land (then part of the Turkish empire). His book on his travels, Innocents Abroad (1869), established his national reputation and he moved to the East.

Ina Coolbrith arrived in California with her mother and stepfather in 1851 and grew up in Los Angeles. Her first poetry was published when she was 11. After her marriage to an abusive husband ended in divorce, she moved to San Francisco in the early 1860s. There she soon received national attention for her poetry and joined Harte in running the Overland Monthly. She seems to have dazzled Harte, Twain, and other emerging literary figures with her poetry, literary advice, conversation, and beauty. When Harte, Twain, and the others left California to pursue fame in the East or in Europe—they were all gone by

Ina Coolbrith is shown here as an established, celebrated poet. Coolbrith, in keeping with the moral conventions of her time, tried to conceal her divorce. She also tried to conceal her family background-that her mother had fled to Salt Lake City and that Coolbrith was the niece of Joseph Smith, the founder of the Mormon Church.

1870—Coolbrith remained. She worked as city librarian in Oakland for many years, encouraged a new generation of writers, including Jack London, and, in 1915 at the age of 74, was named poet laureate of California.