5.1: Crisis and Conflict in the 1850s

- Page ID

- 126963

The new state was born in the midst of crisis and conflict—a national political crisis over slavery, a local crisis of political legitimacy, and conflicts within the state over land, labor, race, and ethnicity.

California Statehood and the Compromise of 1850

Some Americans who opposed the extension of slavery saw the annexation of Texas (1845), the war with Mexico (1846–48), and the acquisition of vast new territory under the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (1848) as part of a slaveholders’ conspiracy to expand slavery. From the Missouri Compromise (1820) onward, new states had entered the Union in pairs—one state that banned slaveryalong with one state that permitted it—so that the numbers of slave states and free states remained equal. Similarly, from the Missouri Compromise onward, slavery had been banned from all of the Louisiana Purchase territory north of 36°30’ north latitude (the southern boundary of Missouri). This seemed to cut off any expansion of slavery because nearly all remaining unorganized territory lay north of 36°30’. Opponents of slavery feared that annexation of Texas and the acquisition of territories from Mexico might open new regions to slavery. When Californians requested entry into the Union as a free state, there was no prospect of a slave state being admitted to maintain the balance between free states and slave states in the Senate. Defenders of slavery took alarm, and some prepared to fight against California statehood.

Once the constitutional convention (see Chapter 4) completed its work, California voters approved the new constitution and elected state officials. The legislature met and, amidst other business, elected John C. Frémont and William Gwin to the United States Senate (senators were elected by state legislatures at that time). Frémont and Gwin, along with newly elected members of the House of Representatives, hurried to Washington to press for statehood and to take their congressional seats once that occurred. They found a raging controversy centered in the Senate. Some of the most powerful political leaders of the first half of the century participated in the debate, including Henry Clay, Daniel Webster, and John C. Calhoun.

In the end, a relative newcomer to Congress, Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois, cobbled together a complex compromise based on Clay’s proposals. In addition to California statehood, the Compromise of 1850 included separate laws that created territorial governments for New Mexico and Utah, pledged federal authority to return escaped slaves from the North, and abolished the slave trade in the District of Columbia. Most southerners opposed California statehood and abolition of the slave trade in the District of Columbia. Most northerners voted against the Fugitive Slave Law and territorial status for Utah. All the bills passed, but only because several moderates, led by Douglas, joined sometimes the northerners and sometimes the southerners to create a majority. California became the 31st state, but the Compromise of 1850 failed to ease sectional tensions.

San Francisco’s Crisis of Political Legitimacy: Vigilantism in the 1850s

During the 1850s, California experienced a crisis of its own, a crisis of political legitimacy. Political legitimacy in a republic means that a very large majority of the population agrees that the properly elected and appointed governmental officials should exercise the authority specified for them by law. Paying taxes, obeying laws, participating in elections, and accepting a judge’s decision are all ways in which individuals denote their acceptance of the political legitimacy of their government. During the 1850s, however, the United States faced a crisis of political legitimacy as abolitionists denied the legitimacy of laws protecting slavery, and defenders of slavery denied that the government had constitutional authority to ban or limit slavery. California in the 1850s also faced a crisis of political legitimacy, as many Californians denied the authority of governmental officials and instead took the law into their own hands. This happened in the gold-mining regions when vigilantes acted as judge, jury, and executioner. But remote mining camps were not the only places where Californians spurned law enforcement officials and turned to vigilantism. San Francisco, the largest American city west of St. Louis, also experienced vigilante versions of justice.

From the raising of the American flag in July 1846 until the first legislature after statehood, San Francisco functioned largely under its Mexican governmental structures. The alcalde (mayor) possessed wide powers, both judicial and administrative. Nonetheless, many San Franciscans felt that the city’s rapid growth had not been accompanied by corresponding growth in the protection of life and property. In 1849, Sam Brannan and other businessmen formed a citizens’ group to suppress ruffians, known as “Hounds.” The citizens’ group— more than 200 strong—sought out and held some Hounds for trial before a special tribunal consisting of the alcalde and two special judges. This tribunal convicted nine men and, because there was no jail, banished them. This procedure did not circumvent the established authorities—the alcalde was centrally involved—but it was a step toward vigilantism as businessmen took the lead in apprehending those they considered the most flagrant wrongdoers.

The first session of the state legislature created a city government for San Francisco, and the city acquired a full range of public officials to enforce the law and dispense justice; however, a series of robberies, burglaries, and arson fires increased San Franciscans’ anxiety over the city’s growing number of Australians, who were often stereotyped as former convicts. A group of merchants and ship captains, led by Sam Brannan, formed the Committee of Vigilance. Almost immediately, they were presented with an accused burglar—an Australian, purportedly a former convict. Committee members constituted themselves as an impromptu court, convicted the accused man, and—despite rescue efforts by public officials—hanged him. Then, claiming support from 500 leading merchants and businessmen, the Committee of Vigilance seized more accused criminals, turned some of them over to the legally constituted authorities, banished others, whipped one, and hanged three more, all Australians. The vigilantes could not imprison their victims because the jail was controlled by the legally constituted authorities, whom the vigilantes were ignoring or openly flaunting. The committee functioned from June to September, although it drew opposition from most lawyers, public officials, and political figures.

The fullest development of vigilantism came in 1856, when Charles Cora, a gambler, killed William Richardson, a U.S. marshal. Soon after, James Casey, a member of the board of supervisors, shot and killed a popular newspaper editor, who had revealed that Casey had a criminal record in New York and had also announced in his newspaper that he was always armed. Casey claimed selfdefense. The Committee of Vigilance was revived with William T. Coleman, a leading merchant, as its president. After hanging Cora and Casey, the committee constituted itself as the civil authority in the city and established a force of nearly 6000 well-armed men, drawn mostly from the city’s merchants and businessmen. They hanged two more men and banished about 20. The committee provoked a well-organized opposition that included the mayor, the sheriff, head

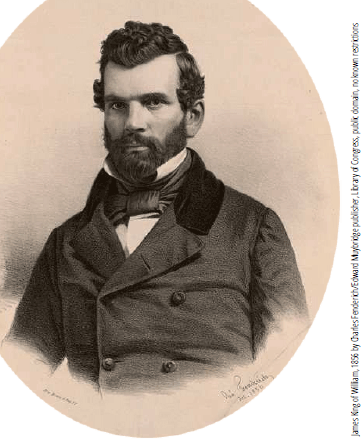

James King of William, the popular San Francisco newspaper editor who was murdered by James Casey.

of the state militia (William T. Sherman), chief justice of the state (David Terry), and other prominent political figures, most of them Democrats. The governor, 30-year-old J. Neely Johnson, tried to reestablish the power of law, but the vigilantes simply ignored him. They eventually established a political party and yielded power only after elections in which their candidates won convincing victories. This party and its successors (under various names and with shifting patterns of organization) dominated city politics for most of the next 20 years, institutionalizing government by merchants and businessmen.

California’s experience with lynching and vigilantism in the 1850s came at a violent time in the nation’s history. Many male Californians routinely armed themselves when in public. An observer noted that more than half the members of the first session of the legislature, in 1850, “appeared in the legislative halls with revolvers and bowie knives fastened to their belts.” Chief Justice Terry carried both a gun and a bowie knife. San Francisco experienced 16 murders in 1850 and 15 in 1851, not counting the men hanged by the vigilantes—a murder rate of between 50 and 60 per 100,000 inhabitants. (There is little comparative data from other American cities for the 1850s: Boston had seven arrests for murder per 100,000 inhabitants in the late 1850s, and Philadelphia averaged four indictments for murder per 100,000 inhabitants in the mid- 1850s. San Francisco’s homicide rate was less than six per 100,000 in 2010.)

The violence of the era provides a necessary context for understanding the lynchings and vigilantism. Even so, the question remains: Are the vigilantes best understood as outraged citizens taking matters into their own hands and cleansing their community, or as an organized effort to overthrow the legally constituted authorities? Josiah Royce, an early historian writing in 1886, called the events of 1856 “a businessmen’s revolution”—that is, he considered it an illegal action in defiance of the law. Nearly all subsequent historians have agreed that action outside the law was unnecessary and that the businessmen who made up the Committee of Vigilance scarcely pursued—much less exhausted—legal courses of action. They were too preoccupied with business to bother with politics, and then, when they took action, they took a shortcut. Nonetheless, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, most popular accounts of the vigilantes glorified them, treating them as saviors of the city. And, from 1856 until at least the 1930s, in times of community crisis, there were usually some who invoked the spirit of the vigilantes and urged extralegal action.

Violence and Displacement: California Indians in the 1850s

For most California Indians, the 1850s and 1860s were years of stark tragedy. Of the estimated 150,000 Native Americans in California in 1848, only 31,000 remained by 1860, after 12 years of the Gold Rush and a decade of statehood. Even so, the censuses of 1860 and 1870 showed California with the largest Indian population of any state.

Long before the Gold Rush, California Indians had become the major part of the work force on the ranchos along the coast between San Francisco and San Diego and inland from San Francisco Bay. Many of them continued some traditional ways, including gathering acorns for food, dancing, and the sweat lodge. At the same time, they adopted practices from their Mexican employers and priests. Some (nearly all women) intermarried with Mexicans, many of whom were themselves mestizos—of mixed Spanish, Indian, or African ancestry. Many other Native Americans were familiar with European practices, traded with the ranchos, and occasionally worked for wages. Sometimes they traded with the Californios; other times they raided the Californios, stealing cattle and horses.

John Sutter’s settlement near the present site of Sacramento was built largely by Indian laborers. Sutter also maintained a hired Indian army to protect his land and livestock and to wage war on Indian raiders. Other whites who entered the Central Valley in the early 1840s emulated Sutter and sometimes contracted with him for Indian labor. Thus, on the eve of the American conquest, many whites looked to California Indians as an important source of paid labor. This expectation was a direct outgrowth of the Spanish and Mexican approaches to converting and “civilizing” the Indians and turning them into laborers on the missions and ranchos. By contrast, in the eastern United States, the usual practice in new white settlements was to push Indians further west rather than integrate them into new settlements.

In the earliest stages of the Gold Rush, Mexican patterns prevailed, as Indians were hired to work in mining operations. They learned the value of gold and of their labor and expected to be paid accordingly; however, a flood of Americans who knew the eastern practices but not the Mexican ones soon descended on California, expecting that part of “subduing the wilderness” would include expelling the Indians. Some of the newcomers objected to competing with Indian labor, especially when the Indian laborers worked for Californios. Others, with no real evidence, viewed Indians as dangerous and sought to have them removed from the mining regions because they were considered a threat to white miners.

At the same time, many Native Americans suffered from severely reduced access to traditional food sources. Cattle ate the grass that formerly had produced seeds for food. Large-scale hunting to feed hungry miners decimated the deer and elk herds. Thus, Indians were increasingly barred from wage labor in the mines at the same time that they were deprived of many traditional foods.

Violence soon flared. In a continuation of patterns from Mexican California, some Indians raided white settlements and stole food, cattle, and horses. Others forcibly resisted when white men made advances toward Indian women. Thefts by Indians often brought the burning of the village thought to be responsible. If an Indian killed a white, local militias or volunteers often destroyed the nearest village and killed its adult males and sometimes women and children. Undisciplined volunteers often struck out at any Indians they found, whether or not they had any connection to a crime. Some local authorities in the 1850s even offered bounties ranging from fifty cents to five dollars for Indian scalps.

The killing of individual Indians and even the massacre of entire villages were repeated over and over, sometimes by groups of miners, sometimes by local or state authorities. More than one historian has suggested that genocide is the only appropriate term for the experience of California Indians during the 1850s and 1860s. Only rarely did anyone seek to punish white men for beating or killing Indians. On the contrary, state power was more often used against the Indians. In 1851, Governor Peter Burnett announced his view that it was inevitable that war be waged against the Indians until they became extinct, and he twice sent state troops against them. His successor, Governor John McDougal, authorized the use of state troops in 1851 in what was called the Mariposa War. In these instances, state troops engaged in the brutal killing of Indians and destruction of Indian villages. When local authorities presented the state with bills for their often undisciplined forays against Indians, the state routinely paid them.

Both the state and federal governments attempted to regulate relations between California Indians and whites. The previous practice of federal authorities, who had exclusive constitutional authority to deal with Indian tribes, had been to negotiate treaties by which Indians yielded their traditional lands in return for other lands, almost always to the west of white settlements. In California, however, it was no longer possible to move Indians west. In California in the 1850s, federal authorities negotiated with Indians to surrender title to large parts of their lands in return for promises that they could retain small tracts, or reservations. Federal policymakers envisioned the reservations as places where Indian people could live and be protected from the dangers of the surrounding white society, taught to farm, and educated. This new approach owed a good deal to the violence visited upon the California Indians in the Gold Rush regions.

In 1851, federal commissioners began to negotiate with representatives of Indian groups. They eventually drafted 18 treaties that set aside 12,000 square miles of land in the Central Valley and the northwestern and southern parts of the state. When the treaties went to the Senate for approval, however, they were rejected due to opposition from Californians. New federal agents were then appointed, and the process started over, even as violence against Indians mounted. In the mid-1850s, a few small reservations were finally created, some embracing only a few square miles. Some Indians from the Central Valley were moved north, to live on the new reservations in northern California. Most, however, continued instead to live in the midst of white settlements, working for wages on ranches and farms and following some traditional practices. A few moved into the mountains, avoiding white settlements as much as possible.

As federal authorities stumbled toward creating reservations, state officials also asserted their authority over California’s Indian peoples. In 1850, the first session of the state legislature approved the Act for the Government and Protection of the Indians. The law permitted Indians to remain in the “homes and villages” that they had long occupied. The law also provided for the indenturing of Indian children, either with consent of their parents or if they were orphans. As a result, many Indian children became “bound labor”—obligated to work without pay in exchange for food, shelter, and necessities—until age 18 for boys and 15 for girls. Adult Indians not employed for wages were subject to arrest for vagrancy and could then be hired out by the courts. Burning of grasslands (see Chapter 1) was made a crime. Penalties were established for anyone who compelled an Indian to work without wages, but Indians were prohibited (under a different law) from testifying in court against whites, so violations were difficult to establish. The historian Albert Hurtado concludes that “the 1850 Act for the Government and Protection of the Indians protected them very little and governed them quite a lot.”

The Politics of Land and Culture

When the news of gold first became known, Californios were among the first to rush to the gold country. Thousands of immigrants from Mexico, especially Sonora, and others from elsewhere in Latin America, especially Chile, soon joined them. Whether citizens or immigrants, Spanish-speaking miners found themselves derided as “greasers,” harassed, assaulted, and sometimes lynched. Eventually violence and harassment, along with the Foreign Miner’s Tax of 1850 (see Chapter 4), drove many Latinos from the gold country. Some of the immigrants returned to their homes, but others took up permanent residence in the existing pueblos, especially San José, Santa Barbara, and Los Angeles.

The Gold Rush, however, was good for some rancheros, who prospered because of the increased demand for cattle to provide food to the massive influx of gold seekers. Cattle prices tripled between 1849 and 1851, and 50,000 head of cattle from southern California went north for slaughter. Los Angeles, still with a Mexican majority, boomed both from cattle sales and from sale and distribution northward of horses and mules brought from northern Mexico to be sent to the mining regions.

Nearly all Californio landowners found themselves struggling to retain their land. Though the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo guaranteed existing landownership, those who poured into California from the eastern United States brought significantly different expectations regarding landownership. In the eastern states, land was carefully surveyed, and each plot was precisely located. Under the Preemption Act of 1841, settlers could select a parcel of undeveloped land, build a home on it (often called “squatting”), farm the land, then buy the land from the government for $1.25 per acre. The intent of federal land policies, though not always the reality, was to encourage family farms and to discourage land speculators. For would-be squatters, land that was apparently not lived on or actively farmed was often considered available forsquatting.

In Mexican California, there had never been any formal land surveys. Land grants were large and vaguely defined, often based on natural markers (streams or boulders, for example) rather than precise survey lines. For the largest California ranchos, much of the land seemed unused, at least by the standards of the eastern United States. Even before the United States acquired California, some Americans had squatted on land in California. After the war, many more did the same. Some did so in the expectation that the Preemption Act would be applied in California. Some did so on the assumption that, having won the war, they could claim what they desired. Some did it with full knowledge that Californios already owned the land.

One of the most important tasks in integrating California into the American legal system was to verify and record land titles—the official record of landownership. Earlier experiences in Louisiana and Florida (both previously Spanish possessions) suggested that the process invited manipulation, fraud, and litigation. When Frémont and Gwin took their seats in the U.S. Senate in 1850, they immediately proposed federal legislation to clarify land titles. That law, the Gwin Act (1851), created a board of three commissioners, appointed by the president. Those claiming land presented their evidence of ownership to the commissioners. If others claimed the same land, they too introduced evidence. If the commissioners accepted the evidence of ownership, the title was considered valid. If the commissioners rejected the evidence, the land passed to federal ownership. A federal agent participated in the hearings to challenge dubious evidence. Either the person claiming the land or the federal agent could appeal a decision, first to the federal district court and then to the U.S. Supreme Court. Of several proposals that went before Congress for clarifying land titles, the Gwin Act was probably the most cumbersome, time-consuming, and potentially costly for holders of Spanish and Mexican land titles.

The commissioners worked from early in 1852 until 1856, hearing more than 800 claims. Some were unquestionably fraudulent, but more than 600 were confirmed. Of those confirmed, nearly all were appealed through the courts, and the court proceedings dragged on interminably. Success came with a high price: travel to San Francisco to present arguments and documents, more travel to court hearings, and attorneys’ fees at every step of the way. One historian estimated that the average land-grant holder spent 17 years before securing final title to the land. Another historian estimated that attorneys’ fees involved in defending the Mexican land grants constituted 25 to 40 percent of the value of the land.

During the hearings, squatters often moved onto the most attractive lands, especially in northern California. The squatters formed a large and influential political group and found many public officials receptive to their pleas. Some desperate rancheros sold their claims for whatever they could receive—but such sales could not be final until after the final court decision on the title. Unscrupulous lawyers sometimes saddled their clients with impossible debts, requiring land sales to pay off the mortgages. All in all, most historians who have studied the implementation of the Gwin Act have endorsed the judgment of Henry George, a San Francisco journalist who, in 1871, called it a “history of greed, of perjury, of corruption, of spoliation and high-handed robbery.”

If the northern rancheros found themselves flooded with squatters and lawyers, southern rancheros faced devastating tax burdens. South of the Tehachapi Mountains, Californios remained in the majority. There, they won elections as local officials and members of the state legislature. One Californio, Pablo de la Guerra, was elected president of the state senate in 1861 and was first in line to succeed the governor.

At the constitutional convention, Californio delegates from the south had raised the possibility of dividing California into a northern section, which would become a state, and a southern section, which would become a territory. Though defeated in the convention, the idea of dividing the state persisted. The 1850 session of the legislature created a tax system based on land and other possessions, including cattle, but not wealth, which included gold. These taxes fell disproportionately on the ranchos of southern California, which provided southerners both a reminder that they were dominated politically by the northern part of the state and an incentive for separation. Though southern Californios’ motivation for dividing the state stemmed largely from their desire to separate themselves from northern domination and regain control over their taxes, some, especially white newcomers from the slave-holding South, also saw it as a way to create a new slave state.

Throughout the 1850s, the state legislature received proposals to divide the state. In 1859, the legislature approved a popular vote in the southern counties on the issue of division. The vote was two to one in favor of division, and the results were forwarded to the federal government for action, but nothing was done in Congress in 1860. The next year found the nation preoccupied with civil war. This effectively ended the possibility for creating a separate state or territory in which Californios and other Latinos might be numerically dominant. And, within a short time, English-speaking Americans soon outnumbered those who spoke Spanish in southern California as well as in the north, and political power slowly passed from the hands of the Californios.

The effort to create a separate state or territory in southern California marked one attempt by Spanish-speaking Californians to retain their culture and political autonomy. Political efforts to secure bilingual schools in Los Angeles (unsuccessful), to insist on implementation of the constitutional provision requiring Spanish translations of official documents (a losing struggle), and to serve on local political bodies represented other examples. Such efforts came largely from members of the old, landowning Californio families. Most elite Californios, at least in the south, were accorded a level of respect and even honor by their new, English-speaking neighbors. Some historians have suggested that, in fact, many of them were co-opted into the emerging English-speaking power structure and that, despite their attempts to secure recognition for their language and culture, they made little serious effort to protect the large numbers of landless Mexican laborers and farm workers from economic exploitation.