4.1: The War Between the United States and Mexico

- Page ID

- 126957

On the eve of the war between the United States and Mexico, the northern states and the provinces of the Mexican Republic were increasingly being influenced by American commercial interests. The opening of the Santa Fe Trail in the 1820s and the increase in Yankee hide and tallow ships in California created new economic ties with the Mexican upper classes. In 1836, the Anglo Americans in Texas had waged a war of independence from Mexico and declared themselves a sovereign state, the Lone Star Republic. The Texans longed to join the United States but were prevented from doing so until 1845 because of opposition from northerners, who feared adding another slave state. In the interim, the Texans carried on a thriving trade between their ranches in central Texas and Louisiana. In 1842, they unsuccessfully tried to conquer New Mexico to add its lands to their new republic. Finally, in 1845 the United States admitted Texas to the Union as a slave state, with the Texans asserting that their southern boundary was the Rio Grande. Mexico, on the other hand, pointed out that the historic boundary between Texas and the province of Coahuila had always been the Nueces River. The friction between these two claims provided the spark that eventually led to an armed conflict between U.S. and Mexican troops in 1846.

There had been other rebellions in Mexico’s northern provinces. In 1837, the lower classes in New Mexico led a rebellion against the Mexican government’s centralizing administration, seeking more autonomy for their village governments. The Mexican upper classes soon crushed this rebellion. But they too had their grievances with the Mexican government, primarily its strict trade regulations. The merchants and other wealthy people of northern New Mexico grew to depend on the manufactured goods brought to them over the Santa Fe Trail. The value of goods brought overland from St. Louis increased every year, and Hispano trading families in Santa Fe grew rich. Meanwhile, the upper classes knew from past experience that the unstable Mexican government would not be able to preserve their interests.

The Californios were also dissatisfied with the Mexican government (see Chapter 3) and had deposed several Mexican governors, replacing them with their own native-born hijos de país. The rebellion of 1836, which placed Juan Bautista Alvarado in power, increased the self-confidence of Californio landholders that they could control their own affairs. They were growing wealthy from the hide and tallow trade, much of it illicitly conducted with American, British, and French ships, and some of them talked openly about separating from Mexico and joining the United States.

Though the upper classes in the Mexican north were growing more and more economically dependent on the Americans, and some of them were contemplating political separation, the vast majority of the more than 100,000 Mexican citizens who lived on the frontier, including Hispanicized Indians, were opposed to being forcibly annexed by the United States. They valued their independence and cherished their culture. When the war came, most realized what was being lost, and they fought back.

Manifest Destiny

In May 1846, the United States declared war on Mexico. Though the causes of this conflict were many, perhaps the most important was the spirit of expansionism called Manifest Destiny. Thousands of Anglo Americans believed it was God’s will that they move west and north across the entire North American continent, occupying the lands of the Mexicans and Indians and casting them aside in the process. As John O’Sullivan, editor of the Democratic Review and popularizer of the term “Manifest Destiny” wrote in 1845, “the Anglo-Americans alone will cover the immense space contained between the polar regions and the tropics.” For most, however, Manifest Destiny had an economic dimension, justifying a more efficient use of natural resources by the industrious Anglo-Saxons. Mixed in with this sentiment of justifiable economic conquest were attitudes of the racial superiority of the Anglo American people. Walt Whitman, the poet, expressed this view in 1846 when he wrote, “What has miserable inefficient Mexico—with her superstition, her burlesque upon freedom, her actual tyranny by the few over the many, what has she to do with the peopling of the new world? With a noble race? Be it ours to achieve that mission.” Or, as a writer for the New York Evening Post put it in 1845, “The Mexicans are Aboriginal Indians, and they must share the destiny of their race.”

Beginning with Andrew Jackson’s presidency in the 1830s, successive American administrations had offered to purchase California from Mexico in order to give the United States a window on the Pacific and to fulfill the nation’s destiny. Mexico had repeatedly refused these offers. In 1845, President James K. Polk sent John Slidell to make yet another offer to purchase California and to settle a dispute over the boundary between Texas and Mexico. The Mexican government refused. President Polk offered as justification for his declaration of war on Mexico the fact that the Mexican government rejected Slidell’s offer of $40 million for the purchase of California. There were other, more immediate, causes as well. Texas had been annexed as a state in 1845, but the Mexican government did not accept the Rio Grande as the southern boundary of Texas. In the spring of 1846, Mexican troops attacked Zachary Taylor’s troops on what they believed was their own country’s soil. President Polk claimed these skirmishes were proof of a Mexican invasion of the United States. On May 13, 1846, he asked Congress for a declaration of war. In his war message, he recalled the failed attempts at negotiating grievances between thetwo countries and blamed Mexico for starting the war. “As war exists,” he argued, “and, notwithstanding all our efforts to avoid it, exists by the act of Mexico herself, we are called upon by every consideration of duty and patriotism to vindicate with decision the honor, the rights, and the interests of our country.” Though the declaration of war passed by a large vote in the Congress, there were opponents. Some southerners, including John C. Calhoun, feared that a war with Mexico would result in renewed conflict over slavery in the territories and would admit to the Union a new class of non-white citizens—a dangerous precedent for the slaveholding south. Some northerners opposed the war because they viewed it as a conspiracy of slave owners trying to acquire new lands to expand their “peculiar institution.” Some of them, including Henry David Thoreau and Abraham Lincoln, also opposed the war on moral grounds, since, in their view, the United States was clearly the aggressor nation.

An important factor in the agitation for war was the desire of many American expansionists to annex California. The value of California harbors for the China trade and the threat of possible British or French occupation of this area combined to heighten interest in acquiring not only California, but all of the territory between California and Texas—the present-day states of New Mexico and Arizona and parts of Nevada, Utah, and Colorado—as well. In 1844, presidential candidate Polk had listed the acquisition of California as one of the objectives of his presidential administration.

The Californios had been aware for some time of the expansionist designs of the Americanos. The mistaken capture of Monterey by Commodore Thomas ap Catesby Jones in 1842 sounded a clear warning of the expansionist objectives of the United States. The U.S. consul in Monterey, Thomas Larkin, had been sending letters to Washington discussing the possibility of annexation with the cooperation of progressive Californios and American émigrés who shared the belief that their political and economic independence would best be guaranteed by the United States. In 1845, President Polk commissioned Larkin as a secret agent to convince the Californio leadership to break away from Mexico and join the United States. Larkin noted that both Mariano Vallejo and General José Castro were predisposed toward independence from Mexico and union with the United States. But, in the spring of 1846, Polk’s strategy of acquiring California through peaceful intrigue disintegrated, a casualty of agitation for war and the violent actions of Americans in California.

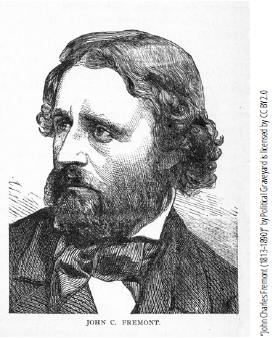

Frémont and the Bear Flaggers

John Charles Frémont, whose father was a French émigré and whose mother was the daughter of a prominent Virginian family, grew up with a burning desire to be famous. He married Jessie Benton, daughter of Thomas Hart Benton, a powerful U.S. senator. Frémont, like his father-in-law, sought to advance his career by promoting western expansion. In 1842, 1843, and again in 1845, Frémont led expeditions across the Rockies into California and Oregon, earning for himself the name “Pathfinder.” In the winter of 1845–46, Frémont, by then commissioned as a lieutenant in the Army Corps of Topographical Engineers, entered California with a group of 62 men and a howitzer cannon. They camped near Monterey. Ostensibly, he was on a mapping expedition, but even today the real purpose of his mission is unclear. Historians have debated whether Frémont was on a secret presidential mission to accomplish the conquest of California. No hard evidence, however, has ever been found to prove that he was part of a plot to separate California from Mexico. Perhaps his actions in California during the early months of 1846 were his own initiatives and not directed by secret orders. In any case, his subsequent actions did assist the American military conquest of California.

When Frémont arrived in California in the spring of 1846, he told General Castro, the military commander of the north, that he was on a scientific expedition. Castro, however, suspected otherwise and ordered Frémont and his men to leave the province. For three days Frémont hesitated. He had his men fortify their positions atop Gavilan Hill near Monterey and defiantly raised the American flag. But after several days of consulting with Oliver Larkin, the U.S. consul in Monterey, and seeing the Mexicans prepare for an attack, Frémont wisely decided to remove his troops from the area and to heed Castro’s orders. He and his men slowly withdrew from California, marching toward Oregon. Upon their reaching Klamath Lake, Lieutenant Archibald Gillespie arrived from Washington, D.C., bringing letters from Senator Thomas Hart Benton. Some historians suspect that Gillespie may have also brought oral instructions from President Polk himself, namely, to assist in the impending conquest of California by arms. We will never know what was said, but soon after Gillespie’s arrival Frémont ordered his men to march back to California. In May, he camped near present-day Marysville, a short march from Sutter’s Fort. In the days that followed, small groups of Americans came to Frémont’s camp and told him of rumors that General Castro was preparing an army to expel all Americans from California.

On June 8, acting on rumors of a possible Californio military action against the American settlers at Sutter’s Fort, Frémont sent a message to William Ide, one of their leaders, suggesting that they come to his camp for protection. On June 10, some 12 or 14 Americans led by Ezekiel Merritt launched a revolt against the Mexican government, capturing approximately 170 horses that were being driven from Sacramento to Santa Clara for use by General Castro’s troops. They now had a choice—either be horse thieves or revolutionaries. They chose the latter. They released the Mexicans who were leading the horses, telling them to tell Castro that the Americans were in possession of Sonoma and New Helvetia (Sutter’s Fort), and then they returned to Frémont’s camp with the horses. Ide remembered that Frémont had encouraged the horse raid and presented to the American settlers a “plan of conquest,” which he would support but not participate in directly. The horse thieves then set out for Sonoma, the residence of General Mariano Vallejo, one of the most powerful Californios and a man who had already voiced his support for American annexation.

In the early morning hours of June 14, 1846, 33 rough and dirty men descended on Vallejo’s home and forced their way into his parlor, demanding the surrender of his command of the Mexican military forces in the region. Jacob P. Leese, Vallejo’s brother-in-law, acted as an interpreter. The mob slowly learned that Vallejo was actually an ally, but they wanted a surrender nevertheless. Negotiations dragged on and Vallejo, with typical Californio hospitality, broke out the aguardiente (brandy). The mob proceeded to get drunk, and after a while someone put together a homemade flag, a grizzly bear with a red star on a white field. William Ide declared their intention to break away from Mexican despotism and establish a republic, along the lines of Texas in 1836. With their flag, the proclamation of independence, and a surrender document, the Bear Flaggers marched to Frémont’s camp with their prisoners— Vallejo, his brother Salvador, Leese, and Victor Prudon, a French resident of Sonoma. Then, with Frémont’s men as an escort, they proceeded to Sutter’s Fort, where Frémont assumed responsibility for the prisoners. In the few days after the capture of Sonoma, the Bear Flaggers had also killed three Californios in a skirmish near San Rafael, and the Mexican army had executed two Americans near the Russian River. Frémont, by his words and then through his actions, joined the rebellion. Within a few weeks, his unofficial actions gained the approval of the U.S. government, as news reached California of the declaration of war with Mexico. The Bear Flaggers were then incorporated into the U.S. Army.

Occupation and Resistance

Congress declared war against Mexico on May 13, 1846, but news of the war traveled slowly. Commodore John D. Sloat, in charge of the U.S. Navy’s Pacific Squadron, had orders to occupy the California harbors in the event of war. Upon hearing of the war declaration, he ordered his ships to sail into Monterey Bay, on July 2. He did not immediately capture the town, however, remembering the earlier embarrassment of Commodore Jones. He waited five days, until learning of the Bear Flag Rebellion. Fearing a British move to seize California, he raised the American flag over the customhouse and announced to the startled populace that “henceforward California will be a portion of the United States.” Sloat reassured the Californios that they would benefit from being part of the United States, and he called on General Castro and Governor Pío Pico to surrender. On July 23, because of ill health, Sloat turned over his command to Commodore Robert F. Stockton, a politically ambitious naval officer. Stockton immediately commissioned Frémont and Gillespie as officers in the newly formed California Battalion, composed of Frémont’s company of engineers plus a contingent of former Bear Flaggers.

The bulk of the fighting in the conquest of California took place in the south. In the summer of 1846, General Castro and Governor Pico joined forces in Los Angeles to await the American advance, but they soon concluded that they were hopelessly outnumbered and outgunned. Both leaders departed for Mexico to seek reinforcements. Meanwhile, Frémont and Gillespie sailed for San Diego and on July 29, after some brief resistance, occupied the town. Californios still controlled the surrounding countryside and continued to harass the occupiers.

Commodore Stockton marched south from Monterey, and following a skirmish his troops occupied Los Angeles, on August 13, 1846. After issuing another proclamation stating that California was now officially part of the United States and promising to respect Mexican political institutions and laws, Stockton and Frémont returned north and left the occupation of Los Angeles in the hands of Gillespie and about 50 soldiers.

What followed was a wave of Mexican Californio resistance against the American invaders. In Los Angeles, the American troops entered private homes and took household goods. Gillespie enforced a strict curfew and forbade Californios to meet in groups. Resentment grew until finally an uprising took place on September 22, 1846, led by José María Flores and Serbulo Varela. Several hundred Californios surrounded the American fortified position and Californio leaders issued El Plan de Los Angeles, calling on all Mexicans to fight against the Americans who were threatening to reduce them to “a condition worse than that of slaves.” Gillespie, with only 50 men in his command, saw that his situation was hopeless, and on September 29 he signed the Articles of Capitulation. The Americans were then allowed to leave the Los Angeles district and march to San Pedro. Soon after that, the new Californio governor, José María Flores, declared California in a state of siege, secured loans to pay for a war, and began to recruit more troops.

For the next four months Los Angeles remained in Californio hands, and their military forces also managed to reoccupy San Diego, Santa Barbara, Santa Inés, and San Luis Obispo. From Los Angeles, Flores sent Francisco Rico, Serbulo Varela, and 50 men to recapture San Diego; this was done without firing a shot in October 1846. They held the town for three weeks until October 24, 1846, when the Americans recaptured the town after a brief battle. According to one eyewitness, the Americans hauled down the Mexican flag, but before it could touch the ground, María Antonia Machado, wife of a local ranchero, rushed into the plaza to save it from being trampled. She clutched it to her bosom and cut the halyards to prevent the American flag from being raised.

In their military forays against the American troops, the Californios had the advantage of knowing the terrain and of being superior horsemen. The Americans had superior weapons and formal military training, but the Californios used guerrilla tactics and effectively won several victories. The Californio lancers won battles at Chico Rancho (September 26 and 27, 1846), Dominguez Rancho (October 8), Natividad (November 29), and finally at San Pascual (December 8).

The Battle of San Pascual was the bloodiest battle fought in California and was both a victory for the Californio forces and evidence of their determination

After orchestrating the Bear Flag capture of Sonoma, John C. Fremont led attacks against Californios in San Diego and along the coast from Monterey to San Luis Obispo.

to resist the American conquest. Early in December, Andrés Pico and a force of 72 Californios lay in wait for the Americans, who were rumored to be approaching from the east. A large body of American troops under General Stephen W. Kearny had, in fact, entered California after marching overland from New Mexico. Kearny’s men numbered 179, including several Delaware Indian scouts led by Kit Carson and a few African American servants of the officers and mule drivers.

Early in the morning of December 6, 1846, the American force attacked the Californio camp in the Indian village of San Pascual. During the charge, the Americans became strung out in a long file, with those on stronger mules and horses far outdistancing those on tired mounts. The few gunshots exchanged were in this first charge, as the Californio troops met the early arrivals some distance from their camp. The Californios raced away, allowing themselves to be chased for about three-fourths of a mile. They then turned and charged the Americans with their lances. It had been raining occasionally for several days, and the Americans’ gunpowder was damp and unreliable, forcing them to fight with their sabers. The Californios were armed with long lances and were expert at using them to slaughter cattle. In the hand-to-hand combat, the Californios had the advantage of superior mounts, weapons, and battle preparation.

Only about half of the American force was actually involved in the battle. The others were in reserve, guarding the supplies and baggage. The Americans were unfamiliar with their newly issued carbines and had trouble loading these guns in the dark and cold. The two groups fought most of the battle—about half an hour—in the dim light and fog. During the battle, the Californios captured one of the American cannons. Finally, the Americans brought up another howitzer, firing at the Californios and causing them to retreat.

Nineteen American soldiers were dead on the field of battle. Two more died later from their wounds. Kearny himself suffered three lance wounds and temporarily relieved himself of command. The Californios had 11 wounded, and one of their group, Pablo Véjar, was taken prisoner. Some of the American deaths may have been from friendly fire in the dim light and confusion. Only one American was killed by a bullet.

General Kearny later wrote that the battle of December 6 had been a “victory” and that the Californios had “fled from the field.” One U.S. soldier, however, wrote that the Americans had been saved from decimation by the Californios’ capture of the American howitzer—an act that made the Californios “consider themselves victorious, which saved the balance of the command.” Later, at the court-martial of General Frémont, Kearny admitted that a rescue party from San Diego had saved them from disaster. Generally the Navy officers, headed by Stockton, considered the Battle of San Pascual a defeat for the U.S. Army. Of course, the Californios considered this engagement a victory, and news of it spread throughout the district.

A month later, on January 29, 1847, another overland army arrived in San Diego. This was the Mormon Battalion, commissioned by the U.S. Army to survey a wagon road between Santa Fe and San Diego. The 350 soldiers traveled more than 1000 miles on foot but arrived too late to participate in the final battles of the war in California. Their numbers augmented a small contingent of Mormons who had settled in southern California near San Bernardino.

California Indians and the War

During the Mexican War, some California Indian groups increased their raids on the Californio ranchos, taking advantage of the weakened defense of the Mexican settlements. The Californios thought the Americans were behind the increased Indian depredations, but the majority of the attacks were probably the work of opportunists who took advantage of wartime chaos. In the early months of the war, though, California Indians did join the Americans. When Commodore Stockton organized his march in San Diego to recapture Los Angeles from the Californio insurgents, more than 100 Indians formed his rear guard to protect the U.S. Army from possible attack. Frémont recruited a small number of local Indians to join his men as he marched from Monterey to San Luis Obispo. And Edward Kern, the American commander at Sutter’s Fort, recruited 200 California and Oregon Indians to help secure the north and to prepare for the reconquest of southern California.

A major tragedy involving the natives and the Californios during the war was the Pauma massacre in southern California. A few days after the Battle of San Pascual, 11 Californio men and youths took refuge in an adobe house on Rancho Pauma, owned by José Antonio Serrano. While they were there, they were tricked into allowing themselves to be captured by Luiseño Indians led by Manuelito Cota. The Indians took the men as prisoners to Warner’s Ranch. There they consulted with a Mexican named Yguera and William Marshall, an American who had married the daughter of a local Indian chieftain. After a short captivity, the captives were tortured to death by thrusts of red-hot spears. Later rumors strongly implicated Marshall in the murders; he hated one of the prisoners, José María Alvarado, who had successfully courted Doña Lugarda Osuna, once the object of Marshall’s affections. Marshall may have suggested that the Indians would be rewarded by the Americans for disposing of the Californios.

Not all Indians supported uprisings against the Mexicans. Within days of the capture of the Californios, a force of natives from San Pascual who were loyal to the Mexican cause set out to rescue the captives, but they arrived too late. After learning of the massacre, a punitive force of 22 Californios immediately set out with a force of friendly Cahuilla Indians. They ambushed a Luiseño force, killed more than 100, and took 20 captives, who were later killed by the Cahuillas. The massacre of the Californios at Rancho Pauma illustrated both the persistence of native animosities toward the Mexicans and the possible manipulation of Indian hatreds by the Americans. News of this massacre, along with memories of previousuprisings and knowledge that the Indians vastly outnumbered the Californios and Mexicans, may have worked to demoralize the Californio resistance movement.

Peace

Despite the Californios’ valiant though somewhat hopeless resistance against the American invaders, the American forces had recaptured all of southern California by the winter of 1847. Following the defeat of the last Californio army near Los Angeles, Andrés Pico signed a surrender agreement at Cahuenga Pass on January 13, 1847. Elsewhere in the Southwest, however, resistance continued. In New Mexico, the Taos Indians, in alliance with some of the Hispano families, rebelled against the American occupiers, killed the American military governor, Charles Bent, and recaptured some of the towns in northern New Mexico. On January 24, 1847, a Hispano-Indian army of 1500 met the Americans at La Cañada near Santa Fe, New Mexico, and were defeated. The Americans marched on the town of Mora and destroyed it, then marched south to surround Taos Pueblo, where the remnants of the resistance had entrenched themselves. In the days that followed, more than 150 defenders were killed and their leaders were captured. Fifteen were tried and convicted of conspiracy, murder, and treason in a display of mock justice. This marked the end of armed resistance in the Southwest.

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

In Mexico, the fight against the American invaders killed tens of thousands of soldiers and civilians in massive clashes of armies, at first in the north, near Monterrey, Mexico, and then in the Valley of Mexico. By January 1847, the

General Andrés Pico, brother of Pío Pico, commanded the Mexican troops at San Pascual. He later signed the Treaty of Cahuenga in 1847 ending the hostilities in California. After the war, he bacame a successful politician serving the California state Senate in 1859. What does this 1855 portrait reveal about Andrés Pico's Mexican identity?

U.S. Army, commanded by General Winfield Scott, occupied Mexico City and waited to hear the results of peace negotiations. Pressed by European creditors,

lacking money to pay their own troops, wracked by internal rebellion, and facing the occupation of their principal cities, the Mexican government had little choice but to sign a treaty of peace, giving in to the Americans’ territorial demands in exchange for the removal of troops from their homeland. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, ending the war, was signed in a town near Mexico City, across the street from the shrine to the patron saint of Mexico, Our Lady of Guadalupe, on February 2, 1848. Among the provisions in the treaty were those specifying the new boundary between the two nations as starting “one marine league due south of the southernmost point of the Port of San Diego” and running east to the Colorado River, then east following the Gila River and an as yet undefined latitude line to the Rio Grande. The Mexican provinces of California and New Mexico now lay within the United States. Articles VIII and IX of the treaty gave assurances regarding the property and citizenship rights of the Mexicans in the newly conquered territories. Article VIII specifically promised to protect the rights of absentee Mexican landholders and to give U.S. citizenship to all Mexicans who wanted it. Article IX promised that Congress would give citizenship “at the proper time” and that the Mexicans “in the meantime shall be maintained and protected in the free enjoyment of their liberty and property, and secured in the free exercise of their religion without restriction.” Finally, the treaty transferred more than 500,000 square miles of Mexican territory to the United States.

The final ratified version of the treaty omitted Article X, which had contained stronger language protecting land rights, namely, that “all grants of land made by the Mexican government or by the competent authorities, in territories previously appertaining to Mexico ... shall be respected as valid, to the same extent if said territories had remained within the limits of Mexico.” The deletion of this article proved fatal to the future of the Mexican landholders in California. In lieu of the deleted article, the final treaty included the Protocol of Queretaro promising to respect land grant titles, but the United States Supreme Court ultimately invalidated it.

The U.S.-MexicanWar awakened new nationalist impulses within Mexico and eventually produced a reform movement led by Benito Juárez in the 1850s. In the United States, the Mexican cession provoked a new and heated debate over slavery in the newly acquired territories. This played a major role in the outbreak of the U.S. Civil War in 1861—the bloodiest conflict in American history.

Within the conquered territories, there were competing visions regarding the future of the territory. The California tribes outnumbered the whites despite the influx of hundreds of American soldiers. Most natives remained unaffected by the war, particularly those living on their traditional homelands away from the settled coastal regions. A few had joined the Americans as scouts and guides during the conflict. Even fewer capitalized on the war to settle old grievances against the Mexicans. Native peoples who had become Hispanicized and who worked on the ranchos and in the pueblos now found themselves with more aggressive masters, the Americans. Indian laborers were still the backbone of the agricultural and ranching industries, and the new American masters inherited a dependence on this labor force.

The Divided Mind of the Californios

On the eve of the American era, the Spanish-speaking Mexicans in California were divided in their attitudes about their status as Americans. Some, like Mariano Vallejo or Juan Bandini, were optimistic about their future under an American regime that they thought would bring political stability and increased commercial opportunities for all. It was impossible for them to envision how much their traditional way of life would change. For now, they saw what seemed to be a new opportunity for their enrichment. Others, like Pío Pico, who had been allowed to return to California, or Felipa Osuna de Marron in San Diego, viewed the American occupiers with great suspicion. They felt sure that the conquest meant more than just the transfer of political sovereignty, for they were aware of the differences between the two cultures and knew that they could not coexist easily. Finally, there were the young men who had fought against the Americans in various battles or who almost immediately felt the outrages of racism as the Americans took over their houses and lands. Serbulo Varela, leader of the recapture of Los Angeles in 1847, along with Salomon Pico, Juan Flores, and scores of other ex-soldiers, became outlaws rather than submit to the Americans. In subsequent decades, their violent actions in response to the American occupation became the source of legend.

It soon became apparent to the Californios that the new American masters believed in their own racial and cultural superiority and that they regarded the mestizo landless classes as little better than Indians. The conflicts between these two groups became evident as thousands of new immigrants began flooding northern California, attracted by the discovery of gold near Sacramento.