6.3: Colonial Conflicts and Wars

- Page ID

- 7901

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)From 1675 to 1748, violence and warfare plagued the British colonies. Several conflicts were fought in North America during this period. The first of these was Metacom’s War, also known as King Philip’s War (1675-1676), a brutal engagement between the New Englanders and the Wampanoag Indians. Shortly thereafter, Bacon’s Rebellion (1676) broke out in Virginia, which also involved disputes with the Indians and the colonial government. Following these conflicts were King William’s War (1689-1697), Queen Anne’s War (1702-1713), and King George’s War (1744-1748). These wars were the North American theater of European wars between the British, French, and Spanish. Escalating imperial tensions at the end of the seventeenth century contributed to each of these wars. In the case of Metacom’s War and Bacon’s Rebellion, the expanding colonial population increased tensions over land between the British colonies and the Indians. In the case of the remaining three wars, tensions between European powers translated into conflict between their colonial possessions.

Metacom’s War

In the early years of British settlement in New England, the colonists and the Indians had a fairly stable relationship because of trade. However, a dramatic increase in migration to the British colonies in the 1630s changed the relationship. When new colonists arrived en masse, hungry for land, it could lead to armed conflict. In 1636, settlers viciously attacked the Pequot in southeastern Connecticut when they refused to pay a tribute to colonial leaders. When the Pequot War ended, the Pequot lost the bulk of their land. Similar problems led to Metacom’s War approximately thirty years later. Ill feelings were compounded by British religious proselytizing amongst the Indians. In 1646, the General Court of Massachusetts passed “An Act for the Propagation of the Gospel Among the Indians.” Over the next decades, a small population of “praying Indians” grew in the New England colonies, primarily in Massachusetts. These Christian Indians were a part of both Indian and colonial society; nevertheless, they were not seen by others as completely belonging to either group. Religious tensions between colonists and Indians, and Indians and praying Indians, also contributed to the outbreak of the war.

Tensions came to a boiling point in 1662 when Wamsutta, the sachem, or political leader, of the Wampanoag, was taken into Plymouth at gunpoint, only to die shortly thereafter of a sudden illness. Many of the Wampanoag suspected that their sachem had been poisoned. Wamsutta’s successor, his brother Metacom, who was called King Philip by the colonists, took advantage of the situation by beginning to build an alliance against English expansionism. Colonists were informed of the alliance by a group of praying Indians. When a group of Indians was found with firearms, the government of Massachusetts forced Metacom to sign a new treaty which bound the Wampanoag to consult with the colonists in the disposal of Indian land and in the affairs of war, and to abide by their decisions. The treaty also named the Wampanoag as subjects of the royal government, bound by the laws of the colony. This 1671 treaty deepened the hostilities.

In 1675, war broke out in the aftermath of the trial and execution of three Wampanoag Indians convicted of the murder of John Sassamon, a praying Indian. Sassamon, a graduate of Harvard, had been an adviser to Metacom and often acted as a mediator for the Wampanoag and the colonial government. In early 1675, Sassamon informed the colonial government that Metacom was gathering alliances for an attack on expanding colonial towns; days after this, he was found dead. Many speculated that Metacom was behind the assassination. The Pilgrims responded by trying and hanging the three Wampanoag responsible for the death of Sassamon. In retaliation, Wampanoag warriors began to loot and burn colonial villages. Better armed than in the Pequot War, the Indians attacked during the summer and fall of 1675 and burned fifty-two of the region’s ninety towns.

The war was short, lasting little more than a year, and brutal for both sides. The Indian alliance grew to include many New England tribes, such as the Narragansett, Nipmuck, Podunk, and Pocanoket. Colonies banded together to form the New England Confederation, which consisted of the Plymouth Colony, Massachusetts Bay Colony, New Haven Colony, and Connecticut Colony. Although the New England Confederacy won the war, their victory was extremely costly. By the end of the war, twelve colonial towns lay in ruins, and many more were heavily damaged. At least 600 colonists died in the conflict, which comprised about 10 percent of the colonies’ men. The war also crippled the colonial economy, costing about £100,000, an incredible sum for the time. For the Indians, about 3,000 died, and more were tried in colonial court and executed or sold as slaves to Bermuda. Some were forced into servitude to local families. Metacom himself was one of the war’s casualties. After he was shot in battle, Metacom’s body was beheaded, then drawn and quartered. Colonists displayed his head in Plymouth for the next decade as a warning against further uprisings. Most significantly, many historians see Metacom’s War as a tipping point in Indian relations; after this conflict, wars against Indians were fought with the purpose of extinction.

Bacon’s Rebellion

As the New England colonists wrapped up their conflict with the Wampanoag, trouble began between Indians, from various tribes, and the Virginia colonists, which eventually produced a civil war in Virginia. The leading protagonists in the conflict were Governor William Berkeley and Nathaniel Bacon, Jr., his cousin by marriage. The war stemmed from their difference on the colony’s Indian policy, but also from larger political and economic tensions in Virginia. Berkeley had been the governor of Virginia since 1641, and so he wielded a great deal of power. For years, he used that power to build support among the wealthiest colonists. He granted them the best public office, the best public land, and a near monopoly over the lucrative Indian trade. When Bacon arrived in the colony in 1675, Berkeley gave him a large land grant and appointed him to the governor’s council (after all, he was family). Bacon, who was a bit of a troublemaker, wanted more power. He sensed weakness in his aging cousin and sought to exploit it. Bacon’s social pedigree rivaled Berkeley’s; thus, he thought he could win support among the smaller planters who Berkeley had overlooked.

.png?revision=1)

As Bacon schemed, tensions mounted between frontier colonists and the Indians. The trouble began in the northern part of the colony. Thomas Mathew, a Potomac River land owner, found himself in a dispute with nearby Algonquian Doeg, and violence ensued. The Virginia militia tracked the Doeg into Maryland where they killed not only their supposed enemy, but also innocent Iroquoian Susquehannock. The resulting Susquehannock War led to a dispute over Indian policy between the governor and his cousin. Berkeley wanted to fight a defensive war by building nine new forts on the frontier; the frontier residents, however, preferred an offensive war. Not only did it give them an opportunity to attack the Indians, whom many blamed for all of their problems, but it was a far less expensive prospect. The frontier residents found a leader in Nathaniel Bacon, who subsequently sought a commission from his cousin to lead forces against the Indians, but Berkeley refused. Bacon proceeded to lead attacks against the Doeg anyway, as well as the Susquehannock and the other tribes in the area, without the commission.

Bacon’s actions prompted the governor to label him a traitor and to expel him from the governor’s council in May 1676. The following month, Bacon’s supporters elected him to the colony’s House of Burgesses which prompted a showdown between Bacon and Berkeley on June 23 in Jamestown. Bacon and his supporters surrounded the statehouse and raised their weapons against the governor. Berkeley then dared Bacon to shoot him on the spot. Bacon chose not to do so, but the burgesses, clearly fearing for their lives, awarded Bacon the commission he wanted and pushed Berkeley to pardon him for his treasonous activities. Berkeley agreed, and then fled the capital. Having won the first round, Bacon turned his attention back to the Indians. He launched an attack on the Powhatan, who had been allies of the English since the 1640s, that forced most of them off their land. Meanwhile, in September, Berkeley briefly took the capital back; however, he lost it almost immediately. At that point, Bacon decided rather than to hold the city he would burn it and go off to attack more Indians. During his hunt, Bacon died of natural causes on October 26, 1676. The rebellion, however, continued until January 22, 1677 when Berkeley finally managed to reestablish his control. English officials then recalled Berkeley to explain the situation; before he had a chance to defend his actions he died on June 16, 1677.

While Bacon’s Rebellion stemmed from a small dispute between a Virginia land owner and the Doeg, its causes ran much deeper. Resentment against Governor Berkeley’s rule had been growing long before Bacon arrived in the colony. Berkeley had curried favor from the wealthiest residents at the expense of the smaller planters and landless tenants. Not only did these “commoners” receive the worst land, they paid high taxes to support the inflated salaries of the governor and the burgesses. Most of the colonists could afford those taxes, just barely, when the price of tobacco was high. However, the price began a steady decline in the 1660s because of the implementation of the Navigation Acts as well as the crown’s trade war with the Dutch.

Since the governor refused to address their grievances, many former indentured servants moved to the frontier. There they faced the sometimes hostile Indians, and, frustrated with their situation, they blamed those Indians for all their troubles. When the Susquehannock War began, Berkeley’s defensive posture proved more than most residents could take because it would invariably mean an increase in their taxes. They turned to Bacon to lead a rebellion. He willingly accepted leadership, because he needed troops to help in his effort to unseat Berkeley and gain more power for the colony’s smaller planters. Not long after the rebellion ended, Lieutenant Governor Alexander Spotswood noted that Berkeley’s refusal “to let the people go out against the Indians” caused the conflict.

For years, contemporaries and historians viewed Bacon’s Rebellion as the first phase of the American Revolution. But in reality, Bacon’s intent and even the intent of his followers was not to end English rule in Virginia. On several occasions Bacon suggested his effort would eliminate a corrupt governor and benefit the crown. Bacon’s Rebellion did little to shift the center of power in Virginia; smaller planters still found themselves marginalized. In fact, it consolidated power in the hands of fewer powerful families such as the Washingtons, the Lees, and the Randolphs. They quickly moved to lower taxes, to implement Bacon’s Indian policy, and to encourage a shift from indentured servitude to slavery. While both forms of labor existed in the colony before 1676, Virginia’s leaders reasoned after the rebellion that if they relied more on slavery than servitude they would have fewer men competing for the available land. The slave population increased rapidly and much of the very poor white population left Virginia for North Carolina. Bacon’s Rebellion in no way marked the end of the colonists’ confrontations with the Indians. In the eighteenth century various tribes became involved in the brewing tensions between Britain and the other European powers in the New World.

Colonial Wars

Towards the end of the seventeenth century, North America became a front of expansion for European wars as military engagements between imperial powers spilled over into their colonial holdings. Each of the wars began in Europe and spread to the colonial holdings, involving not only the British, French, and Spanish colonists, but also their Indian allies. With each conflict, the European powers hoped to eliminate their competition from the New World. None of the conflicts did much to redraw the map of the Americas; however, they did create tensions between the colonies and their respective mother countries.

William’s War (1688-1697)

King William’s War began when the Protestant monarch William of England joined the League of Augsburg in a war against Catholic France, which under Louis XIV sought to expand into German territories. After ascending to the throne in the Glorious Revolution, William felt the need to defend Protestantism and his Dutch Allies. In North America, the war centered on control of the Great Lakes region, the focal point of the fur trade. From the perspective of the English colonists, this war provided the perfect opportunity to take Canada from the French.

The war also saw the establishment of lasting alliances between colonists and native confederacies. The Iroquois Confederacy chose to ally with the British; the Wabanaki Confederacy with the French. In large part, these native confederacies reflected often longstanding regional divisions; each confederacy was made up largely of culturally and linguistically related groups that shared a loose political affiliation. The Iroquois Confederacy and the Algonquin-speaking Wabanaki groups had been fighting a series of wars for regional control and economic and political dominance for many years; the presence of European colonies and the development of the fur trade merely served to intensify their conflict. The economic focus of the war also stretched north to include struggles over control of the Hudson Bay and the lucrative trading posts of the Hudson’s Bay Company.

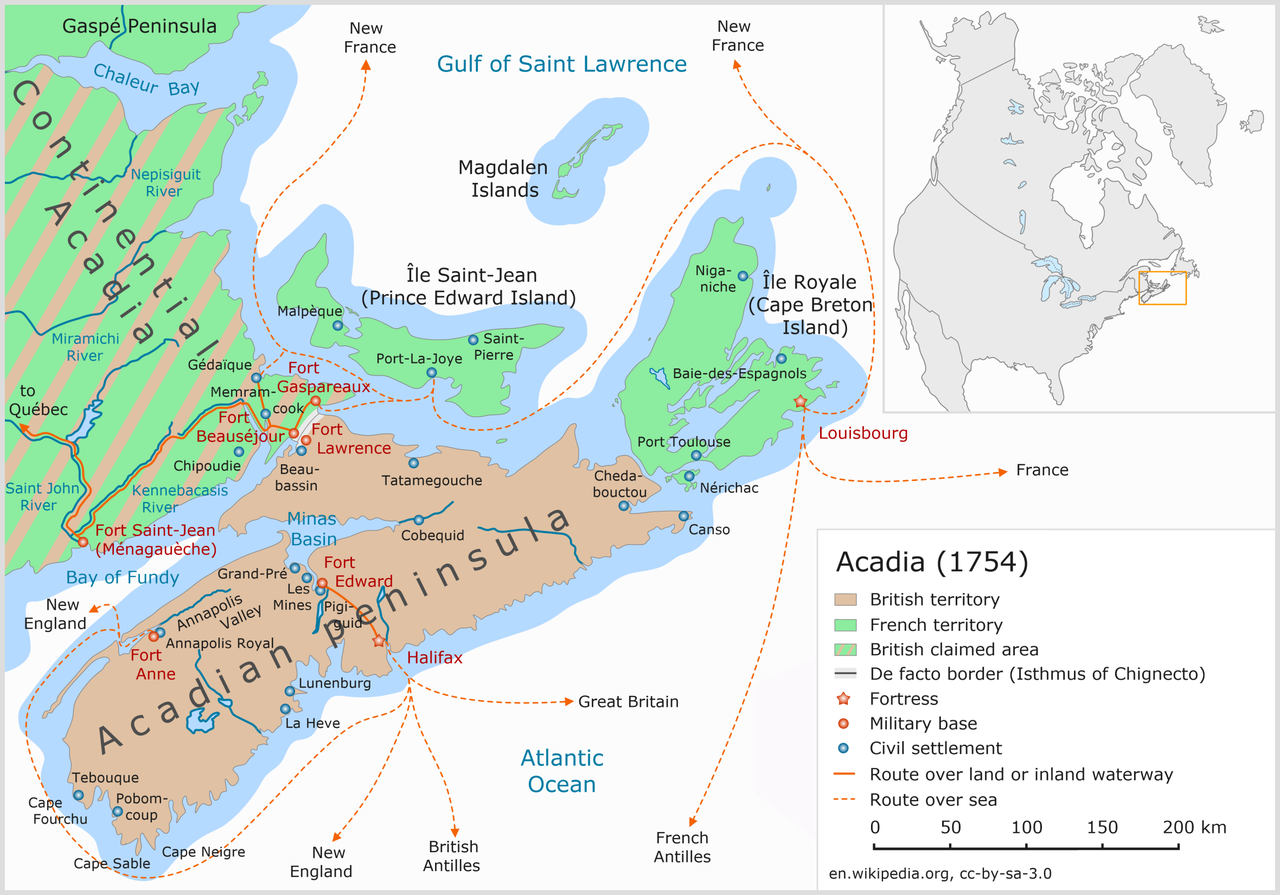

Finally, the war also resulted from land hunger and border disputes between the British colonists of the Massachusetts Bay colony, who were expanding into modern-day Maine, and the colonists of Acadia in New France, who laid claim to much of the same area. The most contested area was the region around the Kennebec River; British and colonial forces led several raids into the Acadian territory. In each instance, they suffered an embarrassing defeat in part because each colony had their own agenda. The war ended with the Treaty of Ryswick of 1697, which returned the colonial borders to what they had been before the war. The treaty failed to establish a lasting peace in North America, and tensions remained; within five years, war had broken out once again in the colonies. More importantly, the British colonists felt disappointed that the crown did not do more to help them assault Acadia. William was more concerned with maintaining an English presence in Ireland than with expanding his holdings in North America. Therefore, his military leaders could not send soldiers or ships to the American colonies.

Queen Anne’s War (1702-1713)

Like King William’s War, Queen Anne’s War emerged in North America when the War of Spanish Succession spilled over into the colonies. In this case, the war was being waged over the possible merging of France and Spain under the Bourbon monarchs. Anne, who succeeded William and Mary to the English throne, sought to prevent a Catholic dominated Europe. While the English won numerous victories in Europe, they struggled to do the same in North America. The war there once again focused on control of the continent. France, Spain, and their Indian allies fought the British and their Indian allies. The war was fought on two fronts throughout the North American colonies. In the south, the English, French, and Spanish fought over control of la Florida; in the north, border disputes once again emerged in Acadia, with the war stretching as far north as Newfoundland.

In 1702, James Moore, governor of the Carolinas, led an attack on Spanish Florida. Although the British forces managed to sack and burn the town of St. Augustine, they were unable to take the city stronghold, the Castillo San Marcos. British and Indian forces were forced to withdraw when a fleet from Havana arrived to reinforce the town. The greatest blow to Spanish Florida came not from the attack on St. Augustine, but with the destruction of dozens of Indian missions. The Spanish population relied on these missions and their populations for labor and for corn; their destruction was quite a blow to the already weakened St. Augustine. Spanish Florida never really recovered from the war either economically or populationally.

In the north, the main combatants were the British and French colonists, along with their Indian allies. From the perspective of the American colonists, one of the more noteworthy events of the conflict came in 1704 when French commanders leading mostly Indian soldiers attacked Deerfield, in western Massachusetts. In the early hours on March 1, the enemy crept into the snowy village. Before they could defend themselves, the attackers set about destroying the village. Within a matter of hours, what historian John Demos calls “a village size holocaust” had ended. The French and Indians took those that survived the onslaught, including the village’s minister John Williams, prisoner and forced them on a long march back to Canada. For those who managed to escape the attack, they returned to find their homes destroyed. More significantly, they found loved ones slaughtered in most gruesome ways or missing entirely. After burying the dead in a mass grave, the villagers worked to secure the release of their family and friends. One of the last to return home was John Williams; however, his daughter Eunice, also a captive, decided to remain with the Indians and she married into their community.

The Deerfield Massacre, though exceedingly brutal, was not exceptional. As Demos notes, “Much of the actual fighting was small-scale, hit-and run, more a matter of improvisation than of formal strategy and tactics.”40 However, on occasion other towns in New Hampshire and Massachusetts became targets of the French. On a larger-scale in the region, like King William’s War, most of the hostilities in the north focused on control of the area of Acadia. The British campaign to take Acadia culminated in the 1710 Siege of Port Royal, the capital of Acadia. After a successful campaign, the British gained control of Acadia, renaming it Nova Scotia. They also tried to take Quebec, but failed when the English admiral in charge of the operation deemed the St. Lawrence River too hazardous. In the Carolinas, Queen Anne’s War and its aftermath coincided with growing trouble regarding trade, land, and slavery between the British settlers and the Indians. In the Tuscarora War (1711) and the Yamasee War (1715-1716), both tribes lost their battle with the settlers and had to give much of their land away. The Tuscarora moved north to join the Iroquois Confederacy after their defeat; meanwhile, the Yamasee moved south and aligned themselves with the Spanish in Florida.

Queen Anne’s War ended with the negotiation of the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713. Anne accepted French control of the Spanish monarchy; however, she also secured more territory in North America, including Acadia and Newfoundland, and of the Atlantic slave trade for thirty years. Overall, this war confirmed the shifting balance of power in North America, with Britain on the rise and France and Spain on the wane. British conquest of Acadia and the weakening of Spanish Florida set the stage for both King George’s War and the more important French and Indian War (1754-1763) because after the Treaty of Utrecht the British focused more of their attention on maritime commerce than territorial acquisition in Europe. And so, securing the strength of their American colonies became of more interest.

George’s War (1744-1748)

After Queen Anne’s War came to an end, the European powers managed to check their rivalry for a number of years largely because their conflicts proved physically and economically exhausting. However, tensions between Britain, France, and Spain remained high, especially in their colonies. Ultimately, events in British Georgia and Spanish Florida sparked another imperial conflict. In the early 1730s, to undercut French power, the British decided to loot Spanish possessions in the Caribbean. When Spanish authorities caught British captains in acts of piracy, they meted out tough justice. For example, in 1731 the Spanish severed the ear of Robert Jenkins, who then presented his ear to Parliament to demonstrate Spanish treachery. In the coming years, the Spanish and the British worked to avoid an open conflict, but they could not contain their hostility. The War of Jenkins’s Ear—the first imperial struggle tied directly to a colonial issue—broke out in 1739. The ongoing Anglo-Spanish rivalry over land in the South as well as the Anglo-French rivalry over the Caribbean sugar trade became interlaced with local concerns in the southern colonies.

Just before the war broke out, the governor of Florida announced that he would grant freedom to any slave who made their way to Spanish territory, which prompted the Stono Rebellion, where slaves took up arms and attempted to march to Spanish Florida. Residents in both British colonies recognized South Carolina’s weakness in the British conflict with Spain. South Carolinians looked the recently founded Georgia to provide a buffer between slavery and freedom. In an effort to protect South Carolina, General James Oglethorpe, a leading trustee in Georgia, led several raids into Florida and managed to capture two forts. However, his efforts to capture St. Augustine failed in 1740. In 1742, the Spanish launched an attack on Georgia, resulting in two skirmishes which the British won. The last major battle in the war came in 1743 when Oglethorpe once again tried and failed to take St. Augustine. After that effort, the focus of the colonial conflict shifted to the northern colonies when the French finally decided to back their Spanish allies. The War of Jenkins’s Ear morphed into King George’s War or the War of Austrian Succession.

As in King William’s War and Queen Anne’s War, the British, French, and their Indian allies launched small-scale operations. The French tended to attack frontier towns in order to divert the British colonists’ attention away from Canada. However, New England residents desperately wanted Canada. In 1745, William Shirley, the governor of Massachusetts, led a small continent in an attack on Fort Louisburg and much to everyone’s surprise managed to take the fort. The victory gave the British the advantage in the North American contest because it made it far more difficult for the French to supply their settlers and Indian allies living down the St. Lawrence River.

In 1746, the colonists sought to capitalize on their victory and move against Quebec. However, much-needed British reinforcements failed to arrive. Even more galling news came in 1748, when word reached the colonies that the war had ended. In the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle, the British traded control of Louisburg, the one thing the colonists were truly proud of, back to the French in exchange for French withdrawal from Indian and Flanders. Essentially when the war came to an end, nothing had changed in North America, which meant the colonists had another war to look forward to.

Summary

The era of the colonial wars was a period of shifting political influence in the colonies. During the course of these wars, colonists and Indian confederacies forged alliances and chose sides. Metacom’s War was a significant engagement between British colonists and local New England native groups. The war was one of the most costly in American history, both in terms of its consequences for the colonial economy and population. It also proved devastating for natives. Bacon’s Rebellion highlighted the ongoing tensions between the colony’s residents and their government over the availability of land, which in turn caused problems with the native population. The remaining colonial wars were intercontinental engagements that saw military action both in Europe and in North America. Each of the three wars saw European political tensions and military action spill over into their colonial holdings. Although each of the wars was fought for different political reasons in Europe, in North America, the wars focused on the balance of political power and control of the continent. The North American war fronts emerged at the periphery where colonial boundaries met, such as Acadia and Florida. Overall, the results of King William’s, Queen Anne’s, and King George’s Wars showed the balance of power in North America shifting to England, weakening the French and Spanish North American holdings.

One of the most contentious areas of struggle in Queen Anne’s War and King George’s War was

- Florida.

- the Carolinas.

- Acadia.

- the Mississippi.

- Answer

-

c

Metacom’s War was significant because

- it marked the shift in policy in Indian warfare to a policy of extinction.

- it allowed the Wampanoag to retake much of Massachusetts.

- although the British won, it devastated many towns and the colonial economy.

- A and B

- all of the above

- Answer

-

d

Queen Anne’s War was significant because the ________helped shift the control of the continent to England

- conquest of Florida

- conquest of the Carolinas

- conquest of New England

- conquest of Acadia

- Answer

-

d