1.2: Concepts of Beauty - Black and White Connotations

- Page ID

- 87705

Norman W. Powell

Eastern Kentucky University

“Color is neutral. It is the mind that gives it meaning.”1 — Roger Bastide

INTRODUCTION

This chapter explores the origins of Western standards of beauty and the related connotations of the colors black and white, particularly interrogating how the color black came to be associated with ugliness and the color white became associated with beauty. These associations have come from such disparate areas as Classical art, Biblical interpretation, historical accounts, fashion trends, and popular culture. This chapter reexamines why the relationship between African Americans and White Americans has historically been so complicated and volatile. It also analyzes the history of discrimination against people of African descent and why, based on biblical interpretations, devout Christians, Muslims, Jews, and other religious populations have supported African slavery. Religion has always played a prominent role in the evolution and the development of ideas, attitudes, and behaviors of humankind, including social constructions of color. According to Nina G. Jablonski, “Associations of light with good and darkness with evil were common in classical and early Christian culture and tended to dominate perceptions of other peoples with different skin pigmentations.”2 In Christian theological teaching, the color white has been historically associated with innocence, purity, and virtue (God). The color black has been associated with evil, death, and darkness (the devil). This symbolic use of the colors of white and black has provided Christianity with a powerful means of identifying and recognizing good and evil.3 This light and dark colorism evolved over time and became associated with people as a result of the expansion of commercial interchange between countries in Europe, Asia, and Africa, “linking blackness with otherness, sin and danger… [into] an enduring theme of medieval, Western and Christian thought.” 4

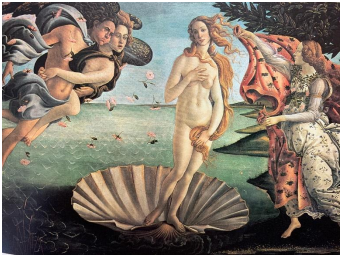

Figure 1. Sandro Botticelli, The Birth of Venus, 1485, tempera on canvas, 172.5 x 278.5 cm, Florence, Galleria Degli Uffizi. Accessed October 30, 2019. https://www.uffizi.it/en/artworks/birth-of-venus

“Western origins of the establishment of the standards of beauty,” according to Sharon Romm, “began around 2,400 years ago in Greece and Rome.” 5 Similarly, Antonio Fuente del Campo noted that “The ancient Greeks believed that a beautiful face was defined in terms of a harmonious proportion of facial features.” 6 These Greek and Roman standards of beauty have been universally transmitted through the ages. Greek statues eloquently expressed and confirmed the aesthetics of the face and the body.

Some other important characteristics of beauty, according to the Greeks, included a straight nose, a low forehead for the look of youth, perfect eyebrows that formed a delicate arch just over the brow bone, and perhaps the most important standard of beauty, the color of hair. Blonde hair was the most prized and highly valued.7

Figure 2. Raphael, Madonna in the Meadow, 1505-1506, oil on panel, 3’ 8 ½” x 2’ 10 ¼”, Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum. Accessed October 30, 2019. https://www.khm.at/objekt-datenbank/detail/1502/

The Romans continued to reinforce and build upon the standards of beauty established by the Greeks. During the Middle Ages, beauty standards for women were clearly defined. Hair was to be blonde and fine like thin golden strands.8 If one’s hair was not naturally blonde, it was to be dyed or bleached. Regarding the eyes, a woman with grey eyes was considered to be especially beautiful. In the fifteenth century, during the Italian Renaissance, concepts of beauty standards evolved into new levels of expression. During this period of artistic innovation, standards of beauty for women and men became universally imprinted in minds throughout the known world. Important vehicles for spreading this new level of beauty criteria were the explosion of paintings and sculptures by the classic Renaissance artists such as Madonna of the Meadows by Raphael (1481), The Last Supper by Leonardo Da Vinci (1495-98), and Birth of Venus by Sandro Botticelli (1482). The above painting, The Birth of Venus by Botticelli, is an example of a Renaissance illustration of the female standard of facial beauty. As these paintings reveal, “Beauty is no quality in things themselves: It exists merely in the mind which contemplates them; and each mind perceives a different beauty.” 9

The works of the Renaissance masters established standards of beauty for the centuries that followed.10 Artistic standards of beauty that related to Black and White colorism, was not only applied to human characters, but also to artistic representations of Christ. Scholars have described how many of those early Western painters intentionally began a “whitening or bleaching” process in their artistic renderings of Christ.11 This effort gradually changed painted images of Christ in the Western world from a Semitic to an Aryan man. It was important that images and representations of the Son of God not be depicted as exuding Blackness or darkness. This gradual “Aryanization of Christ” was consistent with the evolving respective negative and positive associations with the colors of black and white.12

Figure 3. Leonardo Da Vinci, The Last Supper, 1498, tempera and oil on plaster, 15’ 1” x 29’ 0”, Milan, Santa Maria delle Grazie. Accessed October 30, 2019. https://cenacolovinciano.vivaticket.it/index.php?wms_op=cenacoloVinciano.

The Last Supper by Leonardo Da Vinci is an example of classic art in which Christ is depicted with blond hair. The initial dark hair and beard became light or blond. The eyes became a light blue.

In the sixteenth century during the era of Queen Elizabeth I, women had their own concept of beauty. The face of the idealized woman of beauty was a pale white. They plucked their eyebrows and also used white lead as facial makeup to make them appear angelic. Some women even became ill and died as a result of putting the white lead on their skin to make it lighter. Skin that was tan or dark was not considered to be attractive because it was an indication that one was poor and worked outside in the fields. There were two primary factors that greatly influenced popular attitudes associated with the colors black and white. The oldest of these factors was the prevailing societal preferences for people with pale, light skin. This preference for lighter skin was based on the belief that it was visual confirmation that these individuals were not field workers, peasants, or slaves.13 The second factor that had a powerful impact on the preference for white over black was the widespread symbolic colorism reinforced by Christianity and other religions. The Christian associations with the color white were purity and virtue, and associations with the color black were evil and sin.14 Since the Middle Ages, Western culture and practices have been fairly consistent in attitudes toward light skin. Light skin continues to be considered beautiful and dark skin considered less attractive.15

THE CURSE OF HAM

Perhaps the most significant influence on universal attitudes and negative perceptions of people of color is the biblical story of the “Curse of Ham” found in the King James Version (1611) of the Bible in Genesis 9:18-27. The event occurs after Noah and his three sons and their families have left the ark after the Great Flood. Noah’s three sons were Shem, Ham, and Japheth. One day, Noah became drunk from wine made from grapes grown in his vineyard. He fell asleep nude on the floor in his tent. Ham’s two brothers, Shem and Japheth, turned away and did not view their father’s naked body. Ham refused to turn away and saw Noah drunk and naked. Shem and Japheth took a garment, put it on their shoulders, and backed into the tent. They covered Noah with the garment without looking at their father’s nude body. After Noah later awoke and became aware of what Ham had done, he pronounced the biblical curse, “Cursed be Canaan; the lowest of slaves shall he be to his brothers.”16

Historically called “The Curse of Ham,” Noah’s curse was actually directed at Canaan, who was the son of Ham. Noah then blessed Ham’s two brothers, Shem and Japheth. It was after this event that the three sons of Noah went with their families to populate the entire earth. Canaan and his family traveled to settle in the area of the world that is now the continent of Africa. One of Ham’s brothers (Japheth) went to settle in the area that is now Europe, and the other brother (Shem) went to settle with his family in the area known as Asia.

Noah’s statement that Canaan would be the “lowest of slaves” to his two brothers became universally interpreted as an eternal affliction of servitude by God. The Curse of Ham was widespread throughout Europe and eventually spread to America. The Christian Bible does not mention skin color in the story of Noah’s curse, but the conflating of Black skin color with the punishment of eternal servitude later became combined with the original biblical interpretation of the Curse of Ham. The text of the biblical story was translated over centuries by Muslim, Jewish, and Christian writers.

According to rabbinical sources (writings in the Hebrew language by Jewish rabbis during the Middle Ages), another significant component of the Curse of Ham story emerged. In the Hebrew interpretation, all those on Noah’s ark during the flood were prohibited from engaging in sexual intercourse. Ham did not obey this mandate and had sex with his wife. He was then punished by God and his skin was turned black. This rabbinical version of the Curse of Ham did not include slavery or servitude, as did the biblical version.17 Though these were two separate interpretations of the Curse of Ham account, over time, the distinctions were often not noted by other writers and religious leaders.18

In the early Muslim interpretation of the Curse of Ham story, Ham was turned black by God, but was not cursed with eternal servitude.19 When ancient Greeks and Romans first encountered Black Africans, they devised various theories to explain the dissimilarity of the Africans’ dark skin color, which became universally accepted in Greece and Rome and throughout much of the known world. These environmentally determined theories postulated that populations living in the southern areas of the world were burned dark by the sun. Those who lived in the northern areas were pale due to the lack of sunlight. Those living in the middle regions, the Greeks and later the Romans, had skin color that was “just right.” 20

THE EMERGENT DEFINITION OF AFRICANS AS THE “OTHER”

The Tao de Ching set perceptions of beauty in Chinese philosophical and religious tradition: “When people see some things as beautiful, other things become ugly. When people see some things as good, other things become bad.” 21 During the medieval times, Greco-Roman “accounts of the ‘monstrous races’ exhibit[ed] a marked ethnocentrism which made the observer’s culture, language, and physical appearance the norm by which to evaluate all other peoples.” 22 As a result of expanding exploration and commercial interaction beyond the borders of Europe, knowledge of other races and cultures became widespread. The inhabitants from areas in the world such as Africa, Ethiopia, Albania, China, and India became known later to Europeans in the nineteenth century as “The Other.” 23

The physical appearances, behaviors, languages and customs of these diverse populations were viewed as alien by Medieval Europeans. Non-European populations were mistakenly considered very different from the populations of Medieval Europe. The Roman author and naturalist philosopher, Pliny the Elder (23-79 CE), and other writers such as Philo of Alexandria (20 BCE-50 CE), included non-European populations among the groups that became referred to as “monstrous races” due to their marked differences. 24 Leo Africanus, a pre-colonial Muslim diplomat and traveler born in Granada, Spain, was renowned throughout Europe and the known world for his book Description of Africa. The work was highly regarded by academicians and scholastic communities in all of Europe. The book focused on the people and geography of North and West Africa and was based on the many observations and trips made by Africanus to those areas of the world. His vivid description of Africans “brought the African other to the popular consciousness of those that never left Europe.” Africanus described the people as engaging in criminal and “most lewd practices” all day long with “great swarms of harlots among them,” “neglecting all kinds of good arts and sciences,” and “continually liv[ing] in a forest among wild beasts.” 25 The descriptions of Africans in the early Greek writings, centuries prior to Leo Africanus’ book, were equally negative and pejorative. Very few Europeans of that era had ever traveled to foreign and distant areas of the world, such as Africa. Africanus’s published descriptions of Africa and Africans emerged as the primary source of information about the continent and its people for approximately 400 years.26 His work became extremely popular, widely read, and noted for its scholarship and credibility. The fact that the book was also translated into various European languages greatly enhanced its broad readership and wide distribution around the continent of Europe and beyond.

JUSTIFICATION FOR AFRICAN SLAVERY

Color was an instrument of justifying slavery in the Americas. The Portuguese and the Spanish were among the first to bring African slaves to the Americas. In 1542, the enslaving of indigenous Indians in its New World territories was made illegal by the government of Spain, an action that greatly expanded and facilitated the primary use of Africans in the trans-Atlantic slave trade in North America.27 As Davis stated, “It was not until the seventeenth century that…New World slavery began to be overwhelmingly associated with people of Black African descent.” 28 According to Nathan Rutstein, “In all of the original 13 colonies, there was the prevailing belief among whites that the Caucasian race was not only superior to the African races, but that Africans were part of a lower species, something between the ape and the human.” 29

It is perhaps difficult to comprehend how the United States, founded on the principles of liberty, democracy and Christian values, could establish a system as inhumane as slavery. It becomes more understandable with the historical context that Black skin and slavery were considered to be a curse from God. Although slavery was driven by economic need, race and theology were used to justify it. According to Goldenberg, the Bible was used as justification for slavery: “…the Bible…consigned blacks to everlasting servitude…[and] provided biblical validation for sustaining the slave system.” 30 David Brion Davis has written extensively about the impact of the Curse of Ham on slavery and attitudes toward African Americans in the antebellum era. Davis stated that “the ‘Curse of Ham’ was repeatedly used as the most authoritative justification for ‘Negro slavery’ by nineteenth-century Southern Christians, by many Northern Christians, and even by a few Jews.” 31

HISTORICAL CHALLENGE TO ATTITUDE CHANGE

Historically, the relationship between African Americans and White Americans has been complicated and volatile. While a number of underrepresented groups in America have had their various experiences with prejudice, mistreatment, and discrimination, the African American experience has been unparalleled. The attitudes toward Blackness and African Americans that have evolved over centuries have become deeply rooted in the culture and resulted in harm all around: “it wasn’t only white children who were influenced…it was drilled into the cerebrums and hearts of children of color as well, planting in them the seeds of inferiority.” 32 It is doubtful that “the vast population of whites and blacks in the United States comprehends the extent to which we have been equally affected by this extensive negative journey we have shared.” 33 Europeans brought the first group of enslaved Africans to what would become the United States in 1619. 34

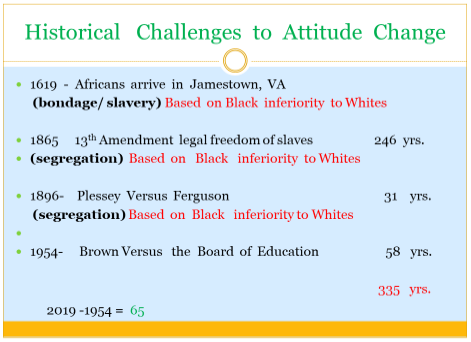

Figure 4. Norman Powell, “Historical Challenges to Attitude Change,” PowerPoint Presentation, 2001. In possession of author.

According to Hine, Hine, and Harrold, “the precedent for enslaving Africans” was set in the British sugar colonies during the seventeenth century. An economy that initially depended on the labor of White indentured workers evolved into a system that became primarily dependent on African slave labor. This economic dynamic and demand stimulated the push for the mass enslavement of Africans.35 From the time the first Africans arrived in Jamestown, Virginia, in 1619, until 1865, the relationship was based on African inferiority to White superiority. That was a period of 246 years in which negative attitudes and practices toward African Americans became institutionalized and psychologically embedded.36

The 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution was passed in 1865, making slavery illegal in the nation. Segregation emerged as the public policy that continued the relationship and discriminatory practice of White superiority and Black inferiority. The Plessy v. Ferguson U.S. Supreme Court ruling posed a prominent legal challenge to the practice of segregation of the Black and White races. The justices of the court ruled in favor of upholding the discriminatory policy. The practice of White superiority was reaffirmed by the nation’s highest court for another 58 years. In 1954, civil rights activists and other groups led by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People challenged the practice of segregation in the public schools. The decision of the U.S. Supreme Court was historic. It reversed the Plessy v. Ferguson decision and made segregation in public schools unconstitutional. Brown v. Topeka Board of Education, known for its “separate but equal” finding, laid the groundwork for future legal decisions that were to make illegal the practice of segregation in institutions throughout the nation.

From 1619 to 1954, the relationship between Blacks and Whites was based on White superiority and Black inferiority. This was the relationship between these two groups for 335 years. The critical factor that determined one’s group membership was the colors of black and white. It has been only sixty-five years since the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that segregation was unconstitutional. Clearly it has been and will continue to be a formidable challenge to reverse attitudes and practices over 65 years that have been in the process of institutionalization for 335 years.

The colorism against blackness still persists. Nina G. Jablonski stated, “The single most powerful factor reinforcing the preference for lightness in the last 150 years has been the dissemination of images in the popular media.” 37 For example, Josh Turner’s “The Long Black Train,” a popular song on country music radio that is also sung in churches, contains negative associations with the color black that are still widespread. The melody is beautiful, and the lyrics include spiritual references. A closer examination of the words and the messages shows that the song continues to reinforce and spread the negative connotations of the color black that began hundreds of years in the past. The song warns the listeners to stay away from and avoid that long “black” train, if they want to be saved and go to heaven. It also goes further to state that the person driving the train is the devil:

Cling to the Father and his Holy name,

And don't go ridin' on that long black train.

I said cling to the Father and his Holy name,

And don't go ridin' on that long black train.

Yeah, watch out brother for that long black train.

That devil's drivin' that long black train.38

AFRICAN AMERICAN SELF-DETERMINATION AND REJECTION OF WHITE CHARACTERIZATIONS

Lisa E. Farrington stated, “African men have been portrayed in Western high art and popular culture as brutish; African women as lewd; and for much of Western history women in general have been characterized as submissive.” Farrington continues to make the point that depictions of Africans and women in Western historic records have been grossly misconstrued.39 Since slavery was first legalized in Massachusetts in 1641, African Americans have protested and fought against racism, brutality, discrimination, and injustice. Over these many decades, countless courageous African Americans have emerged to challenge the formidable systems of institutionalized racism and flagrant double standards. Individuals like Sojourner Truth, Frederick Douglass, Ida B. Wells, W.E.B. DuBois, Malcolm X, Fannie Lou Hamer, and Martin Luther King, Jr. waged legendary protests against racism, violence, and injustice. Each took leadership responsibility to speak truth to power, to put their lives in jeopardy, and to fight for African American legal and social liberation.

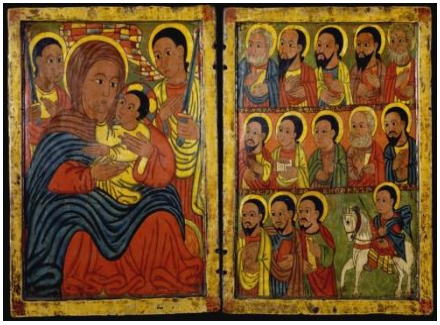

Another leader, who arose during the 1920s, a decade of rising Black Pride, was Marcus Garvey. With over one million members, Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) was one of the largest Black organizations in American history. As both a Pan-African and a Christian, Garvey developed interest in the Ethiopian Orthodox Church. “In addition to urging Blacks to Africanize God,” writes scholar Darren Middleton, “Garvey advised all descendents of slaves brought to the New World between the fourteenth and nineteenth centuries to go ‘back to Africa.’” 40 An ancient work of religious art by fifteenth century Ethiopian painter Frē Seyon (see Fig. 5) exemplifies a distinctly African brand of Christianity and image of the Holy Mother and Child that attracted Garvey. Clearly, this piece is in direct contrast to the classic GrecoRoman standards and renderings of members of the Holy Family by Western Christian artists.

Figure 5. Frē Seyon, Diptych with Mary and Her Son Flanked by Archangels, Fifteenth Century, tempera on wood, left panel: 8 7/8” x 7 13/16” x 5/8”, Baltimore, The Walters Art Museum. Accessed October 30, 2019. https://art.thewalters.org/detail/5751/diptych-with-mary-and-her-son-flanked-byarchangels-apostles-and-a-saint/

The 1960s and the 1970s were eras of significant activism in the push for African American political, social justice, pride, and equality. Black Power and Black Nationalism contributed to the powerful sense of Black consciousness. One of the significant results of these movements was the African American acceptance of their Blackness. The color “black,” which had the historic connotations of “evil” and “ugliness,” was now deemed to be “beautiful.” Tanisha C. Ford writes about Black college students’ adoption of “soul style” during the Civil Rights and Black Power Movements, not only from a fashion perspective but also in a transformation in attitudes about their identity. Ford makes the point that Black college students embraced their Blackness and aimed to change the negative connotations of the color black: “Dissociating blackness from ugliness, they were actively celebrating the beauty of having dark skin and tightly coiled hair.” 41

Another important impact of these movements was the African American acceptance and identification with Africa and their African roots. There was an explosion of initiatives, activities, and projects that expressed and advocated Black pride and consciousness.

In the 1960s and 1970s, the wearing of African clothing and jewelry became very popular, and the Black Pride Movement was demonstrated and expressed in almost all aspects of daily life, from African clothing and jewelry to the “Afro” hairstyle among African Americans and even with some Whites. The 1960s and 70s in the United States, during those activist years of Black Pride and Black Power, were times when African Americans were able to make the statement that they would no longer be defined by White standards and by White culture. The rejection of White standards of beauty is a demonstration of the “Black is Beautiful” movement. 42 Carson, Lapsansky-Werner, and Nash stated it best: “Black identity was no longer imposed by a Jim Crow system, but African Americans could now choose to identify themselves with their rich history of struggles against racial barriers.” 43 The success of African fashion designers, such as Yodit Eklund, suggests that Black identity and beauty standards can appeal to a global marketplace while it can also be politically and socially conscious.44

CONCLUSION

This chapter has focused on historic standards of beauty and origins of negative connotations of the colors black and white. Western beauty standards have developed over many centuries. The early Greeks and Romans played a significant role in establishing the initial standards that are still recognized throughout today’s world. The African American people and their struggle for liberation have established their own standards of beauty and positive connotations for the color black. Some of the most notable conclusions about this analysis include, but are not limited to, the concept that beauty is a social construct. Another is that the colors black and white are also constructs with associated meanings and connotations that have been passed down for many centuries. The negative and positive connotations of these two colors have been widely spread and shared through numerous means. Powerful avenues for the universal spread of these connotations and standards have included the artistic works of classic Greco-Roman artists, biblical and other religious sources, popular music, literature, and numerous other communication means.

With the perpetual advances in media platforms and communication technology, the spreading and sharing of information continues to grow at a phenomenal level and pace. The ability to determine what information is accurate is becoming an increasingly greater challenge. The chapter has provided some history and insights into some of the powerful consequences related to associating negative and/or positive associations to people and colors. Regarding the connotations associated with the colors black and white, it is important to keep in mind that “Color is neutral. It is the mind that gives it meaning.” 45

Discussion Questions

- Using your readings along with life experiences, describe how and why racism has continued to exist and flourish in the United States up to this time. Provide possible solutions to the problem, and evaluate whether or not it can be resolved.

- At different points in history, how have devout Christians, Muslims, Jews, and other religious populations actively supported African slavery?

- Consider the use of black and white as colors of everyday objects and in formal wear and discuss the implications of such color choices. For example, why is a wedding dress usually white and not black? List and analyze other common uses of the colors.

Writing Prompt

In the Brown v. Topeka Board of Education Supreme Court case, the NAACP lawyers utilized the results of an experiment in which young Black girls were asked to choose between Black and White dolls. Based on your reading, analyze how historic standards of beauty factored into the monumental decision of the U.S. Supreme Court to reverse the Plessy v. Ferguson decision of 1896. Using the lyrics from the song “Long Black Train,” discuss and describe the use of the color black and some of the negative associations utilized with the black train metaphor that could be ascribed to African Americans in the song.

1 Roger Bastide, “Color, Racism, and Christianity,” Daedalus, 96:2 (Spring 1967), 312.

2 Nina G. Jablonski, Living Color: The Biological and Social Meaning of Skin Color (University of California Press, 2012), 314.

3 Bastide, 312-27.

4 Jablonski, 157-159.

5 Sharon Romm, “Art, Love, and Facial Beauty,” Clinical Plastic Surgery, 14:4 (October 1987), 579-583.

6 Antonio Fuente del Campo, “Beauty: Who Sets the Standards?” Aesthetic Surgery Journal (May/June 2002), 267-268.

7 Romm, 579-583.

8 Ibid.

9 David Hume, Essays: Moral, Political and Literary (London: William Clowes and Sons, 1904), 234.

10 Hugh Honour and John Fleming, A World History of Art (London: Macmillan, 1982), 357.

11 Bastide, 315.

12 Alison Gallup, Gerhard Gruitrooy, and Elizabeth M. Wiesberg, Great Paintings of the Western World (Fairfield, Connecticut: Hugh Lauter Levin Associates, Inc., 1997), 107.

13 Jablonski, 157.

14 Jablonski, 158.

15 David Brion Davis, The Curse of Ham: Race and Slavery in Early Judaism, Christianity and Islam (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2003), 90.

16 Gen. 9:18-27 (KJV).

17 David M. Goldenberg, Black and Slave: The Origins and History of the Curse of Ham (Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter, 2017), 19.

18 Ibid.

19 David Brion Davis, Inhuman Bondage: The Rise and Fall of Slavery in the New World (New York: Oxford University Press, 2006), 69.

20 Goldenberg, 29.

21 Alan Watts, What is Tao? (Novato, California: New World Library, 2000), 33.

22 Goldenberg, 29.

23 John Block Friedman, The Monstrous Races in Medieval Art and Thought (New York: Syracuse University Press, 2000), 26.

24 Goldenberg, 47.

25 Leo Africanus, The History and Description of Africa, trans. John Pory, ed. Robert Brown, 3 vols. (London: Hakluyt Society, 1896), 97.

26 Tom Meisenhelder, “African Bodies: ‘Othering’ the African in Precolonial Europe,” Race, Gender & Class, 10:3 (2003), 103.

27 Marable, Manning, Nishani Frazier, and John Campbell McMillian, Freedom on My Mind: The Columbia Documentary History of the African American Experience (Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2003) 15.

28 Davis, Inhuman Bondage, 54.

29 Nathan Rutstein, Racism: Unraveling the Fear, (Washington, DC: Global Classroom, 1997), 47-48.

30 Goldenberg, 1.

31 Davis, Inhuman Bondage, 66.

32 Rutstein, 52.

33 Norman Powell, “Confronting the Juggernaut: Establishing Pro-Diversity Initiatives at Institutions of Higher Learning,” in Sherwood Thompson, ed., Views from the Frontline: Voices of Conscience on College Campuses (Champaign, Illinois: Common Ground Publishing, 2012) 15.

34 Davis, Inhuman Bondage, 124.

35 Darlene Clark Hine, William C. Hine, and Stanley Harrold, African-American History (Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 2005), 54-55.

36 Rutstein, 51-52.

37 Jablonski, 158.

38 Josh Turner, “Long Black Train,” track 1 on Long Black Train (2003; Nashville: MCA), compact disc.

39 Lisa E. Farrington, Creating Their Own Image: The History of African American Women Artists (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), 3.

40 Darren J.N. Middleton, Rastafari and the Arts: An Introduction (New York: Routledge, 2015), 8.

41 Tanisha C. Ford, Liberated Threads: Black Women, Style, and the Global Politics of Soul (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2015), 102.

42 Ford, 98.

43 Clayborne Carson, Emma J. Lapsansky-Werner, and Gary B. Nash, The Struggle for Freedom: A History of African Americans, second edition (Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson, 2010), 563.

44 Ford, 188.

45 Bastide, 312.