1: City Life

- Page ID

- 8276

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)As we have seen earlier, urban life in the Americas began millennia before European colonialism. Native Americans built cities such as Tiwanaku on the shore of Lake Titicaca. Begun around 1,500 BCE, Tiwanaku is older than Beijing or Rome. The city’s giant stone walls were begun at about the same time as the Mycenaean fortress on the Athenian Acropolis, a thousand years after the building of the Egyptian pyramids and a thousand years before classical Greek structures like the Parthenon. At the peaks of their cultures, some ancient American cities were the leading centers of world population. Tenochtitlán, which became Mexico City after the fall of the Aztec Triple Alliance, had a population of over 200,000 before European conquest. Although history and popular imagination often focuses more on the unusual customs of these cultures, we should remember that early Americans were extremely successful providing food, water, sanitation, and other services to their large urban populations. The Aztecs’ intensive urban agriculture, for example, was four times more productive than the best farming techniques used by Europeans and Asians at the same time.

Unfortunately, due to the Columbian Exchange and the near-complete collapse of native cultures that followed it, Europeans were able to learn few if any lessons from the urban Indians they conquered. Native cities were rebuilt along European lines, and new cities sprang up based on urban planning ideas familiar from the home countries of the colonists. American cities, as a result, followed in the traditions of Europe, and only slowly adapted to the environments they in which they grew.

Urbanizing America

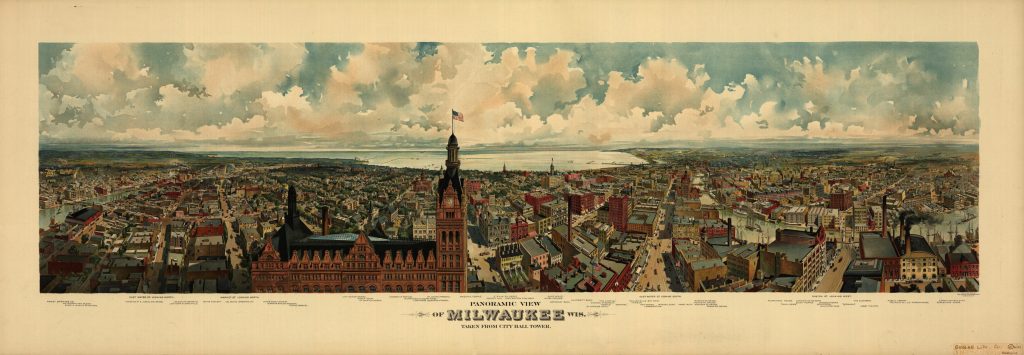

When the United States took its first national census in 1790, fewer than one in twenty of the new nation’s 4 million people lived in cities and large towns. New York was America’s largest city, with only about 33,000 people. But as we have seen, urban America grew quickly. In 1850 there were ten American cities with populations over 50,000. And by 1890, over a hundred American cities were larger than New York had been a century earlier. Cities continued to expand in the twentieth century, becoming homes to more than half the American population for the first time in the 1920 census. After World War II, suburbs expanded and most American cities became the centers of urban-suburban sprawls. By the beginning of the twenty-first century, only about two out of ten Americans lived in rural areas.

As populations expanded, the nation needed more food. And as a growing percentage of Americans living in cities no longer grew their own food, commercial agriculture and robust transportation networks were needed to keep the new city-dwellers fed. In this chapter, we consider other factors necessary for urban growth. Water has often been overlooked, because for most of our history it has been abundant and inexpensive. But it was a vital resource that was indispensable for growing cities. In addition to reliable sources of food, America’s cities required plentiful, year-round supplies of drinking water. Many inland cities such as Detroit, Chicago, Cincinnati, and Pittsburgh were built on the shores of rivers or lakes. Coastal cities like Boston and New York, however, were often surrounded by seawater or by brackish salt-flats. They relied on shallow surface wells that quickly became inadequate for growing populations, and the wells were frequently fouled by that population’s waste. Just as vast quantities of food had to be delivered to growing city populations, equally prodigious volumes of waste needed to be removed. In addition to providing drinking water for residents, as American cities grew, water systems came to play a crucial role in waste disposal.

One of the earliest ways water aided sanitation was that waste was simply dumped into rivers, lakes, and the ocean. When New England textile mills flushed their dye tanks into the Merrimack River, they were only doing what people had always done. The amount of poisons they threw into the river may have been unprecedented, but the practice was nothing new. People throughout history have traditionally dumped their waste in water, where bacteria and marine life have broken down the waste-products and returned them to the ecosystem. Water provides an effective, natural recycling process for organic waste, until the volume of waste becomes too large for the ecosystem to purify.

Although new industries like the textile mills often contributed novel and challenging types of wastes into the natural purification system, the largest source of stress was the growing population. American cities grew tremendously in the early nineteenth century. Boston had fewer than 25,000 residents in 1800. By 1850, there were nearly 137,000, and by 1900 over a half million. New York City grew from 60,000 in 1800 to 515,000 in 1850 and 3.4 million in 1900. San Francisco began the nineteenth century as a village of 897 people. In 1850, the year after gold was discovered in the Sierra foothills, the city had reached a modest population of 21,000. But by 1900, San Francisco had exploded to nearly 343,000 residents. Los Angeles started as a pueblo of 29 buildings and a few hundred residents in Mexican Alta California. In 1850, the population had grown to only 1,600. But by 1900, Los Angeles was home to over 102,000 people and water was becoming an issue.

Water Fortresses, Pigs, Toilets

Coastal cities often contended with challenging environments, especially when they began to grow. Boston was originally built on a peninsula surrounded by ocean and salt marshes, anchored to the mainland by a very narrow connection at the city’s southern tip. New York City occupied the southern tip of Manhattan Island, but the city’s rapid growth quickly exhausted the island’s shallow, easily-contaminated wells. Yellow fever and cholera epidemics in the early 1830s convinced New Yorkers they needed a new water source, and between 1837 and 1842, the city built an aqueduct and a reservoir to carry and store water from the Croton River forty-one miles away. The gravity-fed aqueduct supplied a Receiving Reservoir located at what is now the Turtle Pond in Central Park, and a Distributing Reservoir on Fifth Avenue between 40th and 42nd Streets. With granite walls 50 feet high and 25 feet thick, the Distributing Reservoir looked like a fortress guarding its 20 million gallons of fresh water. The wide promenade at the top of the reservoir’s walls became a popular destination for Sunday-morning socializing. The Croton Reservoir was used until the 1890s, when it was torn down and replaced by the Main Branch of the New York Public Library and Bryant Park.

By 1844, more than 6,000 homes of upper-class New Yorkers had been connected to the public water distribution system and public bathing facilities had been constructed for the poor. Providing public water added to New York’s challenges, though. Initially, most of the water closets in affluent houses were connected to cesspools and pits that had originally been built for solid waste from privies. The small cesspools were almost immediately flooded by the volumes of water and waste flushed into them. Responding to the complaints of its most affluent residents, the city allowed connections to its storm sewers. But the conduits designed to carry excess rainwater were too narrow and the underground pipes’ bends and sharp corners clogged easily. New York’s storm sewer system was quickly overwhelmed. And then there were the pigs.

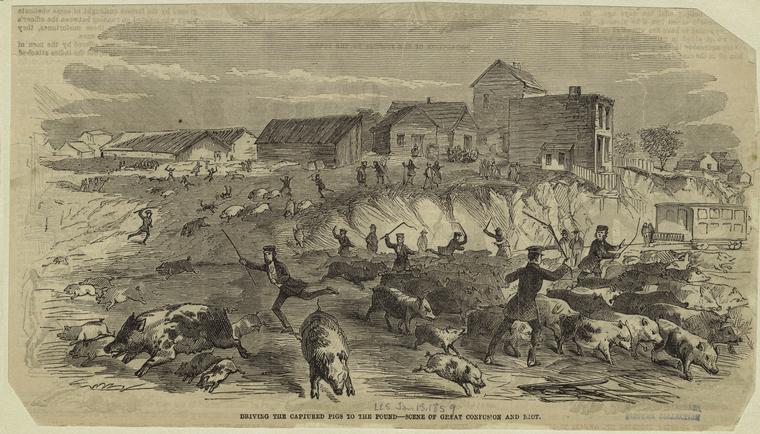

Since the 1810s, city authorities had been trying to outlaw pig-keeping in New York. For generations, poorer city residents had turned pigs loose to forage on garbage until they grew large enough to slaughter. The animals were kept not only in the more open, rural areas north of the growing city center, but lived in basements and spare rooms in crowded tenements. Pigs were dangerous, attacking people and even occasionally killing children. But they were a low-cost food source and they disposed of more waste than they created, so they were tolerated.

When another outbreak of cholera in 1849 was blamed on the roaming scavengers, efforts were resumed to ban city pigs. But removing the animals from city life did not happen overnight. Police conducted raids throughout the early 1850s, finding over 6,000 hogs hidden in cellars and garrets in lower Manhattan. The animals were driven north and the west-side district between 50th and 59th Streets known as Hog Town was raided and shut down in the 1850s. By1860, pigs were illegal south of 86th Street. But hogs were not the only animals worrying New York authorities. In a single month in the summer of 1853, one of the city’s largest waste contractors reported disposing of the remains of 690 cows, 577 horses, and 883 dogs, along with over a thousand tons of butchers’ offal from over 200 slaughterhouses operating in the city.

New York City’s success providing safe drinking water with the Croton aqueduct and its reservoirs encouraged its Massachusetts neighbor, and between 1846 and 1848 Boston completed the 14-mile Cochituate Aqueduct to fill a similar granite water-fortress. The 2.6 million-gallon Beacon Hill Reservoir supplied central Boston with water until the 1870s. Like the Croton Reservoir, Boston’s water sysem provided not only drinking water, but also water for waste disposal. Boston’s elegant Tremont Hotel, built in 1829, was the first building in the city to include indoor plumbing. The hotel initially provided only eight water closets for all its guests, but the novelty quickly caught on and affluent Bostonians began installing toilets and then full bathrooms.

Once toilets and baths became common in Boston homes, the supply of fresh water provided by the Cochituate system was no longer adequate. In 1897, the Nashua River was dammed to create Wachusett Reservoir and an aqueduct was built to carry the water to Boston. But the city’s needs continued to escalate, and the Metropolitan Water Board began planning the world’s largest drinking-water reservoir. The Quabbin Reservoir and Tunnel system was begun in 1926 and completed in 1946. In order to create a reservoir capacity of 412 billion gallons, the Metropolitan Water Board condemned, evacuated, and bulldozed four Western Massachusetts towns: Enfield, Dana, Prescott, and Greenwich.

Municipal water systems were built at such large scales because during an era when pure water was plentiful and cheap, urban planners could reduce cost by meeting all the city’s water needs from a single source. Throughout its water system’s history, almost half of Boston’s water supply has been used to flush toilets. Even today, nearly every American home uses the same source of water for drinking and for all other uses, including cooking, washing, flushing toilets, and watering lawns and gardens. Most municipal water systems provide drinking-quality water to all their residential, commercial, and industrial customers, for all uses. As pure, potable water becomes scarcer and more expensive in some regions, the policy of using the highest quality water for all purposes may need to be revisited.

Boston’s first sewer system was completed in 1884. It carried raw sewage from Boston and surrounding cities to Moon Island in Boston Harbor, where the waste was held in storage tanks and released with the outgoing tide. Although in the late 1880s this solution was considered adequate, the region’s population continued to grow and soon Boston Harbor could not support the levels of waste being flushed into it. Clam beds were closed due to pollution in 1919 and 1933, and by 1940 planning began on treatment plants. Boston’s first sewage treatment plant opened in 1952 and another followed in 1968, halting most of the dumping of raw sewage into the Harbor. Treated sludge was still dumped into the ocean until 1991, when a sludge-to-fertilizer plant was completed. In 2000, to support the city’s still-growing waste disposal needs, an outfall tunnel was built to carry Boston’s treated effluent nine and a half miles out to sea where it is released from 55 risers onto the ocean floor.

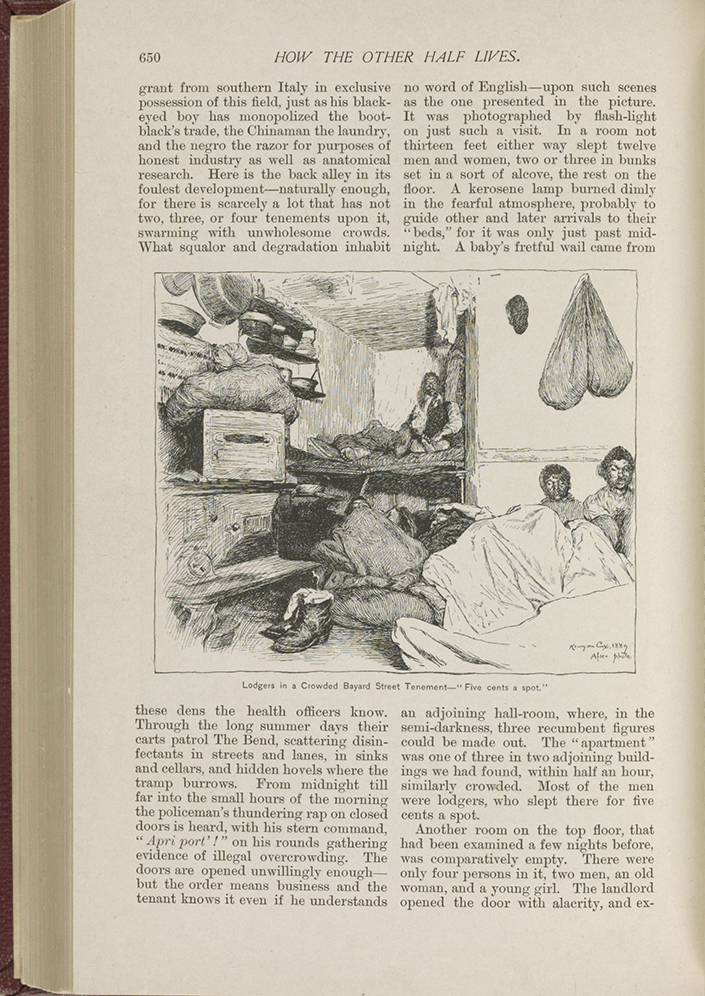

Before indoor plumbing became universal, waste disposal had been much more visible and personal. When the Croton Reservoir began delivering abundant running water to lower Manhattan in the late 1840s, New York City already housed half a million people. Although getting the water into the city was considered a public service, landlords were not required to use the system. The overall population density of the Manhattan was measured at over 41,000 people per square mile in 1880, but in the city’s poorer, more crowded areas, well over 150,000 people were crowded onto each square mile of land. Tenements built on single-family lots 25 feet wide by 100 feet deep, sometimes housed twenty families on a lot that had been designed for one. Although water and sewage were available on many of the main streets, builders were not required to connect tenements to them. Often, to save money, landlords installed a single standpipe to provide running water and built privies in the small backyards. After 1900, revised building codes required new construction to include running water and bathroom facilities in each apartment. It was a long time, however, before all the old tenements were abandoned and torn down.

The adoption of indoor plumbing made human waste disposal a municipal service rather than the responsibility of the people producing the waste. Toilets broke an age-old ecological cycle that had returned nutrients back to the soils that had produced them. What had been a circular resource flow from farm to table and back to farm became a one-way trip. Crops drained farm soils of fertility only to be shipped to cities for consumption and converted into waste that was flushed away. Out of sight, out of mind.

Horses & Mobility

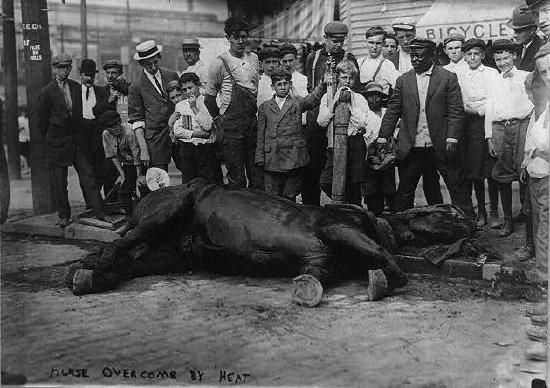

About the same time city people were discovering the convenience of indoor plumbing, transportation technologies such as streetcars, automobiles, and trucks began reducing the horse populations of American cities. In 1880 New York City for example, 1.75 million residents shared the streets with 175,000 horses. The average city horse produced an average of 20 pounds of daily waste, about ten times the output of the average New Yorker. With a population only one-tenth that of the humans, horses created just as much waste every day. And they could not be taught to use the city’s new toilets.

New York City horses also ate a lot of locally-grown hay and oats. Farmers near American cities lost a major market for fodder products when urban horses disappeared. They also lost a big source of soil fertility, because along with the contents of privies, horse manure had traditionally been collected from streets and urban stables and sold back to the farmers to help replenish their fields. Although collecting human and animal manure provided employment for poor city people (often orphans and homeless children) and closed the ecological circle by returning fertility to the soil, night soil and horse manure collection was considered an unsanitary nuisance by many upscale residents and urban reformers.

To add to the waste disposal problem posed by tons of daily manure, draft-horses had a working lifespan of about twenty years, but they were often worked hard right to the end. If only one-twentieth of New York’s horses died in the city’s streets and stables in a given year, they still produced nearly nine thousand half-ton carcasses that needed to be picked up and hauled away. By the end of the nineteenth century, city planners were more than ready to get the horses off their streets.

Although we have considered the rapid growth of American cities, it is important to note that the addition of thousands of new residents from one census to the next, every ten years, was just the tip of the iceberg. City populations not only increased rapidly, they changed even more quickly. During the decade 1880-1890, for example, the population of Boston increased by about 85,000, from 363,000 to 448,000. But the number of people who moved into Boston during that decade was nearly ten times higher. More than 800,000 people passed through Boston between 1880 and 1890. Most stayed for a while and then moved on. The rapid turnover of the city’s residents can be seen in the directories Boston published annually. City directory canvassers found that only about half the homes they visited had the same residents, from one year to the next.

Population historians have discovered that the most mobile city-dwellers were wage-workers and the poor. People who owned businesses and real estate were much more “persistent,” in demographic terms, because they were in a sense anchored by their possessions. Over time, though, the greater persistence of more prosperous residents often allowed them to gain greater political power than the poor, many of whom were not around long enough to organize or often even to vote. Many poor and working-class city-dwellers were also recent immigrants, who needed time to learn the language and customs of their new homes. By 1900, inland cities such as Buffalo, Detroit, Milwaukee, Chicago, and Minneapolis were all the centers of regions where more than 75 percent of people lived in an urban setting. More than three quarters of the residents of these cities were also classified as “Whites of Foreign Parentage,” according to Census language. Many were either immigrants or the children of immigrants, overwhelmingly from either Irish or German-speaking families. Descendants of German immigrants, who arrived in great numbers just as the Midwest was opening for settlement in the mid-nineteenth century, still make up the majority ethnicity of a wide swath of middle America.

Urban Reformers

In addition to engineers and city planners addressing growing cities’ needs for drinking water and sanitation, idealistic nineteenth-century reformers turned their attention to improving social conditions in American cities. Some reformers called attention to the social problems caused by the the cultural dislocation of immigration, economic inequality, and the rapid growth of America’s cities. Others experimented with solutions. This spirit of reform became a key element of the early-twentieth century Progressive movement in politics and culture that tried to correct some of the social inequities of the period known as the Gilded Age.

An early critic of urban inequality was Jacob Riis, a native of Denmark who became one of New York’s most prominent journalists. Riis, born in 1849 into a family of fifteen children, emigrated to New York at the age of 21. Originally trained as a carpenter, Riis became a newspaper reporter specializing in melodramatic accounts of the poverty and misery he found in neighborhoods like New York’s infamous Five Points. When words failed to convey the disparity he witnessed between the glittering world of New York high society and the hopeless world of the poor, Riis turned to photography. In 1889, Riis’s eighteen-page article “How the Other Half Lives” was included in the widely-circulated Christmas issue of Scribner’s Magazine, with nineteen line drawings rendered from his photographs. Riis expanded the material into a 303-page book, which he followed two years later with a sequel called The Children of the Poor. Riis wrote a dozen more books over the next ten years and lectured regularly on social conditions in New York City. His efforts to call attention to the inequities of city life brought Riis to the attention of New York Police Commissioner Theodore Roosevelt, who later called Riis “the most useful citizen of New York.” Although the narratives in Riis’s books echoed many of the stereotypes of his time, his photographs were revolutionary. Middle and upper class Americans discovered there was an “Other Half” living in Gilded-Age America, and some began to devote themselves to reducing the inequality of their time.

One of the most effective social reformers who put her ideals into action providing direct services to poor city people was Jane Addams. Addams was from a prosperous Chicago family, the youngest daughter of a prominent Illinois politician. Born in 1860, Addams lost her mother and several siblings at a very young age, then grew up reading Charles Dickens’s depictions of poor Londoners and revolutionary tracts like the Italian revolutionary Giuseppe Mazzini’s Duties of Man. After visiting London’s famous settlement house, Toynbee Hall, Addams decided to start her own in Chicago. She returned home and opened Hull House in 1889. Begun in an old mansion that Addams purchased, moved into, and renovated with her own funds, Hull House grew to a thirteen-building complex that housed twenty-five women volunteers and served over 2,000 people per week. Services included cultural, recreational, and educational programs, as well as public baths, boys’ and girls’ clubs, and a summer camp. In addition to their service work, Addams’s volunteer staff produced detailed studies of conditions in the Chicago neighborhoods Hull House served.

Addams’s approach to solving problems of urban poverty included equal parts of direct aid to poor city people, scientific study into the roots of poverty and dependency, and political activism to bring this information to the public and elected officials and to advocate change. The success of Hull House in Chicago made it a model for settlement houses in other cities, and Jane Addams and her organization began to influence public opinion and political debate on issues such as education reform, immigrants’ rights, occupational health and safety, child labor, and pension laws. Jane Addams was awarded the Nobel Peace prize in 1931 for her work at Hull House, her advocacy work, and her anti-war activism.

Parks & Suburbs

As cities grew more crowded and their buildings larger and more numerous, residents missed the natural scenery of the countryside and a sense of connection with nature. Some city-dwellers began vacationing in the country, but many could not afford to travel or simply did not have the time. In the mid-nineteenth century, many American cities began building parks to bring a bit of the countryside back into the urban lifestyle.

America’s first city park was the Boston Common, a 50-acre parcel adjacent to the Massachusetts Statehouse, established in 1635. Although the Common is sometimes remembered by nostalgic Bostonians as having once been used as a public pasture, feeding cattle on the Common was limited after 1646 due to overgrazing. Since then, the Common has served as a drilling field for militia, a camp for the British army before the start of the Revolutionary War, a public meeting-place, and as a site for public executions. In 1837 a 24-acre Public Garden was added to the Common.

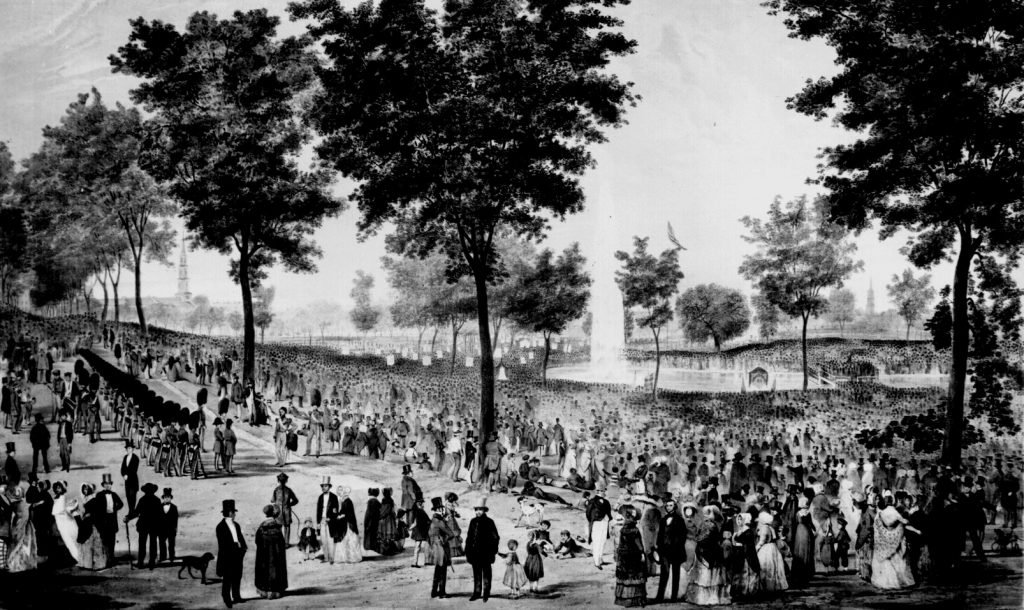

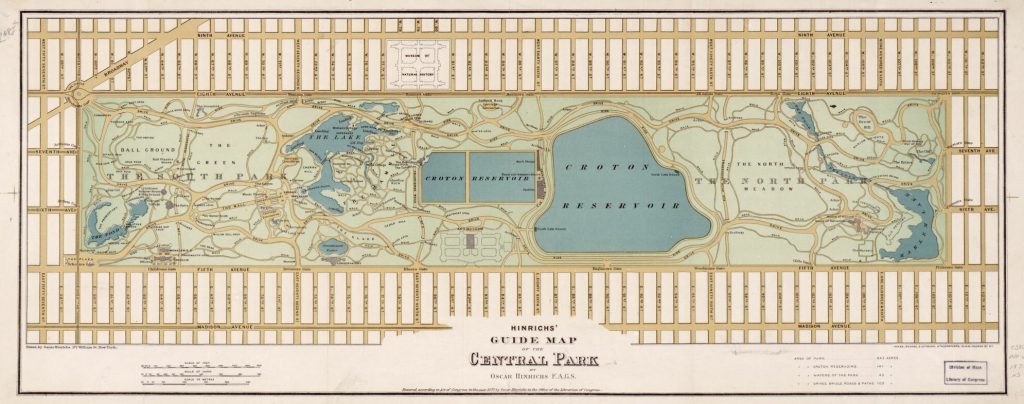

America’s most-visited city park is New York’s Central Park, established in 1853 by an act of the New York state legislature on 700 acres between 59th and 106th Streets. Although at the time most New Yorkers still lived south of the land chosen for the park, central Manhattan land had appreciated rapidly, especially since the opening of the Croton Receiving Reservoir between 79th and 86th Streets in 1842. A small community called Seneca Village was condemned by eminent domain to build the park, forcing about 1,600 people to relocate. Central Park’s 700 acres cost the state $5 million, which was quite a lot of money in 1853.

In 1857, American landscape architect Frederick Law Olmstead and his British mentor, Calvert Vaux, won a design contest and began building what they promised would be “a democratic development of the highest significance.” Central Park would be a place where New Yorkers of all social classes could relax and enjoy a peaceful break from the bustle of the city. The park’s design actually echoed the idyllic landscapes of urban cemeteries, which had become popular destinations for many city-dwellers seeking a natural setting. Sunken roadways called transverses hid crosstown traffic, and separate circulation systems for pedestrians and vehicles helped maintain a peaceful, natural ambiance. In 1873, the park was expanded to its current size of 843 acres.

In addition to countless smaller parks, there are now over 140 urban parks in the Americas greater than 1,000 acres, including 116 in the United States and 12 in Canada. The largest is the Serra da Catareira in São Paolo, Brazil (160,124 acres) and the smallest is Stanley Park in Vancouver, Canada (1000 acres). But statistics do not tell the whole story. Vancouver, a densely populated city of 603,500 people, has 3,200 acres of parkland and devotes over 11% of the city’s land area to parks. Parks provide recreational areas and give city-dwellers a needed sense of connection to the natural world. Ecologists have recently suggested that city parks also help clean urban air and reduce the heat island effect, making cities more livable for the growing percentage of Americans who occupy them.

As transportation networks improved in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, it became increasingly practical to commute to work in the city. Residential suburbs began to appear along railway lines and later along highways. Unlike the older satellite towns that had once supplied cites with food, animal fodder, and other goods, suburbs mostly supplied people. And unlike towns and small cities that had traditionally been economically self-contained, suburbs were mainly residential. Suburban economies generally depended upon the consumption spending of residents who earned their incomes in nearby cities.

The first suburban developments in America were New York City’s bedroom communities in Westchester County. Originally a rural area along the Hudson River north of the city, Westchester County became a weekend retreat for wealthy New Yorkers toward the end of the nineteenth century. When convenient rail service from Grand Central Station made it practical for commuters to leave the city every night, developers began building residential communities for affluent city workers. Soon middle and even some working class New Yorkers began following the examples of their bosses and managers, and moving their families to the suburbs.

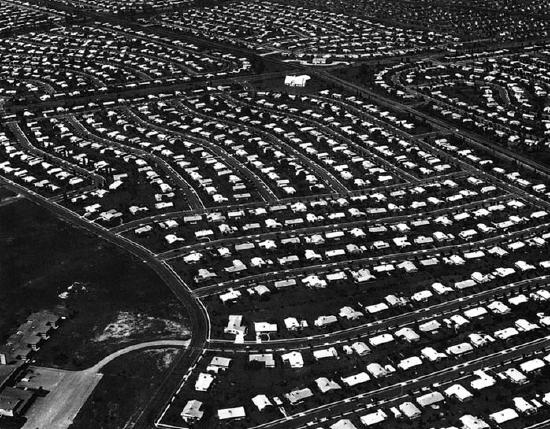

After World War II, a long period of prosperity and growth created opportunities that had not been available during the Great Depression and the war years. A rapidly-expanding American middle class looked for a place of their own in the suburbs. Communities like Levittown, a 1950s development of over 17,000 affordable, ranch-style homes about fifty miles from Manhattan, sprang up along rail lines and highways close to major cities. Zoning laws controlled the placement of commercial and residential buildings, creating a separation not seen in cities and heightening residents’ reliance on automobiles. Suburban families increasingly depended on their cars not only to get to work in the cities, but to visit shopping centers and malls, to get to recreation and entertainment centers, and to get the kids to little league or band practice. Many families acquired a second car, and then sometimes another for teenage children. Today, there are 250 million automobiles in America; substantially more than the number of licensed drivers.

In some cases, expanding suburban development coincided with the migration of black families to northern cities. Segregation, Jim Crow laws and the ongoing lack of opportunities for black people in the South caused many to look for a better life in the North. Many urban whites reacted to the changing racial mix of the cities by fleeing to newly-created suburbs, and some communities instituted discriminatory policies to prohibit or discourage black Americans or other people deemed undesirable from buying houses in white suburbs.

The first suburbs were usually built immediately outside the city limits of the urban centers they served. Communities such as Brookline and Newton Massachusetts, Angelino Heights and West Hollywood outside Los Angeles, and Scarborough and Parkdale outside Toronto were all first-tier or “streetcar” suburbs. As automobile ownership and interstate highways expanded, second and third tier suburbs developed in widening rings. In many cases, nearby towns and cities that had once been self-sufficient became part of an expanding sprawl around major cities. The U.S. Census Department had to develop an entirely new way to categorize places. The Census now uses the designation Combined Statistical Area to describe places that contain major cities, smaller satellite cities, towns, and suburbs. There are 169 Combined Statistical Areas in the United States, with a total population of about 250 million. In other words, about 78 percent of America’s 320 million people live in urban/suburban complexes. The other 70 million Americans live in the sparsely-populated white areas on the map.

As suburban populations grew, some businesses followed their workers and moved facilities into the suburbs. Ring roads and beltway highways attracted newer industries that were not already located in city centers. An early example was Route 128, a semicircular state highway through Boston’s suburbs that became known as “America’s Technology Highway” before the advent of the Silicon Valley. And much of California’s own epicenter of technology, located on the southwestern shore of San Francisco Bay, is ringed by Highways 280 and 101. When many of the most innovative firms began locating themselves in the suburbs, cities rapidly lost their most affluent citizens, the businesses those people worked in, and the places where they shopped. The effect on urban tax bases was often visible in services cities became unable to provide and infrastructure they could no longer afford to maintain.

Recently, residents of many American cities have expressed concern over the high level of dependency involved in an urban lifestyle. As more Americans have crowded into urban/suburban environments, a larger percentage of the population have become separated from the agriculture, energy production, and resource extraction that make their lifestyles possible. Cities have begun exploring local energy generation, urban farming, and recycling to regain some control over the production sides of their economies. These efforts not only reduce the economic dependence of cities, they offer people opportunities to participate in the re-imagining of urban life. But changing American city life is not going to be easy. Increasing global trade has shifted both resource extraction and the manufacture of most consumer products outside the boundaries of the United States. Urban Americans depend on the world outside their city limits more than ever. We will explore that world in the next few chapters.

Further Reading

- Jane Addams, The Subjective Value of a Social Settlement. 1892.

- Edwin G. Burrows and Mike Wallace, Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898. 1999.

- Marc Reisner, Cadillac Desert: The American West and its Disappearing Water. 1986.

- Ted Steinberg, Gotham Unbound: The Ecological History of Greater New York. 2014.