5.3: Spiritual Life: Public & Secret

- Page ID

- 22754

Along with language, black people also created a unique African American culture through religious expression and practices. By the eighteenth century, many of the people brought from West Central African to be enslaved in the Americas were familiar if not converted to Catholicism. Before the American Revolution most black Catholics lived in Maryland and in the areas that were to become Florida and Louisiana. In the American colonies controlled by Catholic powers—the Portuguese, Spanish and French—African slaves were baptized as Christians from the earliest days of slavery. But in the British-controlled Protestant colonies, planters showed little interest in converting their slaves. Many feared that to accept slaves as Christians was to acknowledge that “Negroes” were entitled to rights accorded other Christians—a dangerous message as far as they were concerned.

As early as 1654, the English made provisions for “negro” servants to receive religious instruction and education. Some planters made provisions in their will that their “negro servants be freed, that they should be taught to read and write, make their own clothes and be brought up in the fear of God.” By 1770, it had become the duty of masters acquiring free “negro children as apprenticed to agree to teach them reading, writing and arithmetic” (Russell [1913] 1969:138).

Despite owner opposition, and the inability of some Africans to speak or understand English, by 1724 Anglican clergymen had established small groups of African converts to Protestant Christianity in a number of parishes in Virginia and Maryland. Their greatest success was in Bruton parish, Williamsburg, eight miles north of Carter’s Grove, where approximately 200 Africans were baptized.

The slaves who lived at Carter’s Grove apparently chose to attend Bruton Parish church over other Anglican churches located nearer to their homes and attended by the Burwell Family. Although the journey to Willamsburg was longer it was also an occasion when they could meet with friends or relatives from Bray and Kingsmill Farm or other surrounding plantations or farms (Russell [1913] 1969:138). In the last half of the eighteenth century 1,122 “negro-baptisms were recorded” in Bruton Parish by the Anglican church (Wilson 1923:49).

The motivation for attending church was as likely to be a rare chance to meet without fear of planter intervention as it was spiritual. Christians came from different generation groups and were as likely to be field hands as they were to be domestic servants in the great houses. Christians included Africans and native-born African Virginians. For some, the motivation was a reward of larger food rations or additional clothing. For others it was an opportunity to learn to read.

South Carolinian colonists were the first to make systematic efforts to Christianize enslaved Africans and African Americans in the early eighteenth century. Anglicans believed literacy was essential. As Anglican missionaries reached out to enslaved Africans in South Carolina and Georgia they tried to teach at least a few to read. Planters were hostile to the idea of slave literacy. They resisted by passing a law in 1734 that slaves could not leave the plantation on “Sundays, fast days, and holy days without a ticket,” that is a pass. Fears of insurrections led by literate slaves, such as the Stono Rebellion in South Carolina, resulted in passage of the New Negro Act of 1740, which curtailed the missionaries’ freedom to teach slaves to read and write English. In spite of the law, Alexander Garden, an Anglican missionary, established the Charleston Negro School in 1743. The school lasted twenty years. Garden purchased and taught two African American boys to read and write and they became teachers of others. Over the next four years Garden graduated forty “scholars.” At its peak in 1755, the school enrolled seventy African American children. This was a miniscule number considering there were about 50,000 Africans and African Americans in the colony. It was, however, a start (Frey 1991:20–24).

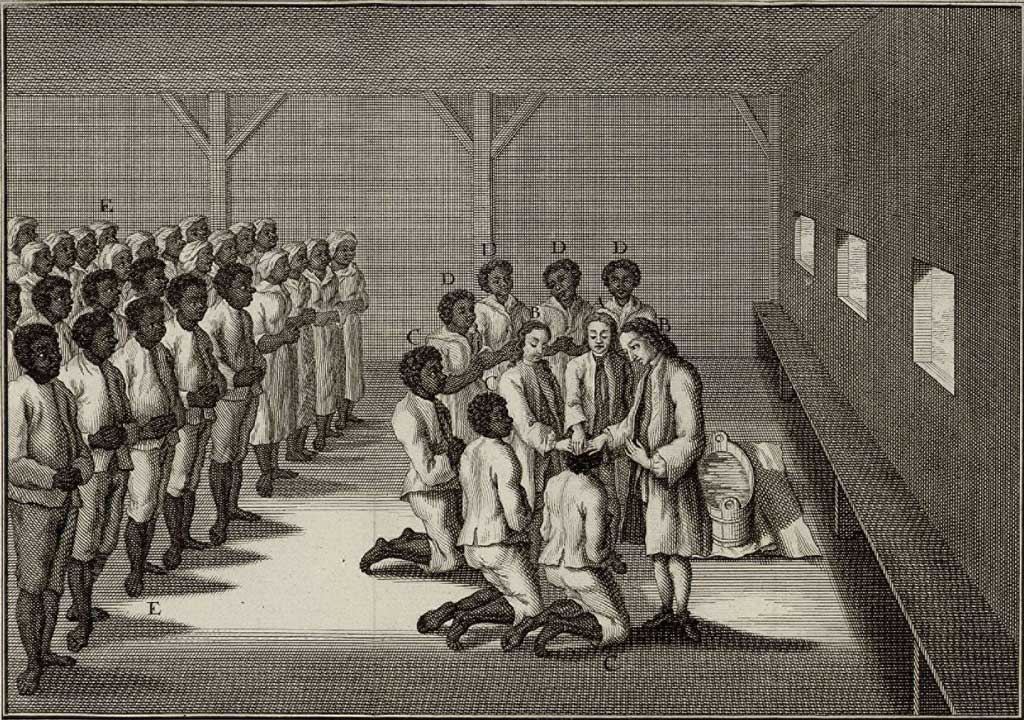

Figure 5-2: DE Unitas Fractum Bild 04 by David Cranz is in the Public Domain .A 1757 drawing titled, “Exorcism-Baptism of the Negroes,” that shows African American slaves being baptized in a Moravian Church in North Carolina.

Figure 5-2: DE Unitas Fractum Bild 04 by David Cranz is in the Public Domain .A 1757 drawing titled, “Exorcism-Baptism of the Negroes,” that shows African American slaves being baptized in a Moravian Church in North Carolina.

Other Protestant sects also reached out to African slaves in southern colonies. The Presbyterians established a church on Edisto Island, South Carolina between 1710 and 1720. Thirty years later, Moravians, mostly missionaries to American Indians, established a North Carolina church that received African slaves into the congregation.

During the first Great Awakening of the 1740s, itinerant Baptist and Methodist preachers spread the Gospel into slave communities. The Baptists and Methodists did not insist on a well-educated clergy. They believed true preachers were called and anointed by the spirit of God, not groomed in institutions of higher learning. If a converted slave demonstrated a call to preach, he could potentially preach to both black and white audiences. Consequently, African American slaves tended to most often join or attend Baptist and Methodist churches. (Raboteau 1978:133–134; Creel 1988; 78–80). (3) The first independent African American churches that slaves established in the 1770s were a part of the Baptist denomination: Silver Bluff Baptist Church in South Carolina, First Baptist Church of Petersburg, Virginia, and First African Baptist Church of Savannah, Georgia. (1)

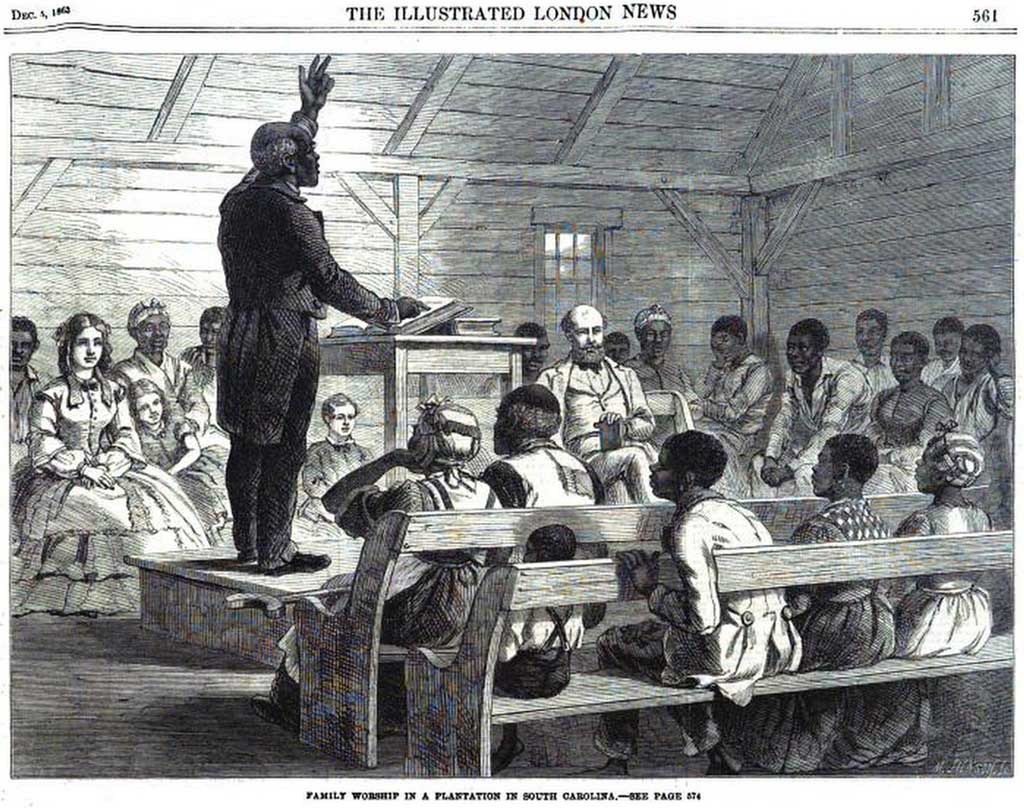

Family Worship in a Plantation in South Carolina (page 561) by unknown is in the Public Domain .From The Illustrated London News , December 5, 1863, p. 561.

Family Worship in a Plantation in South Carolina (page 561) by unknown is in the Public Domain .From The Illustrated London News , December 5, 1863, p. 561.

A recording of a prayer from a Baptist church in Livingston, Alabama (1939)

An audio element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can listen to it online here: http://pb.libretexts.org/temp/?p=1821

Prayer by John A. Lomax (Collector) has no known copyright restrictions. (8)

Public and Secret Religious Experience

The first Great Awakening accelerated the spread of Christianity and a Christian culture among African Americans. The Presbyterians launched the first sporadic revivals in the 1740s. Baptist revivals began in the 1760s followed ten years later by the Methodists. With religious conversion came education for the enslaved, at least education to read the Bible. By 1771, itinerant African American Baptist preachers were conducting services, sometimes secretly, in and around Williamsburg, Virginia.

Aside from the names of a small number of runaway slaves who were described as fond of preaching or singing hymns, many of the early African American preachers remain anonymous. The few names in the historical record were men of uncommon accomplishments in organizing churches, church schools, and mutual aid societies in the South and as missionaries in Jamaica and Nova Scotia. All were born into slavery in Virginia. All were Baptists. George Liele, born in 1737 was the first African American ordained as a Baptist minister. He preached to whites and slaves on the indigo and rice plantations along the Savannah River in Georgia. He was freed during the Revolutionary War in the will of his owner. Liele was forced to flee with the British to Jamaica in order to escape re-enslavement by his owner’s heirs. Before he left, he baptized several converts, including Reverend Andrew Bryan, who would continue his work in Georgia and as missionaries extend it abroad.

“Our brother Andrew was one of the black hearers of George Liele, … prior to the departure of George Liele for Jamaica, he came up the Tybee River … and baptized our brother Andrew, with a wench of the name of Hagar, both belonging to Jonathon Bryan, Esq.; these were the last performances of our Brother George Liele in this quarter, About eight or nine months after his departure, Andrew began to exhort his black hearers, with a few whites… (Letters showing the Rise of Early Negro Churches 1916:77–78)

Liele also baptized David George, a Virginia runaway. These men, and others, formed the nucleus of slaves who were organized by a white preacher as the Silver Bluff Baptist Church between 1773 and 1775. George began to preach during the Revolutionary War, but later fled with the British to Nova Scotia where he established the second Baptist church in the province (Frey 1991:37–39).

In 1782, Andrew Bryan organized a church in Savannah that was certified in the Baptist Annual Register in 1788 as follows:

“This is to certify, that upon examination into the experiences and characters of a number of Ethiopians, and adjacent to Savannah it appears God has brought them out of darkness into the light of the gospel… This is to certify, that the Ethiopian church of Jesus Christ, have called their beloved Andrew to the work of the ministry….” (Letters showing the Rise of Early Negro Churches 1916:78).

As the eighteenth century ended, the First African Baptist Church in Savannah erected its first building. By 1800, Bryan’s congregation had grown to about 700, leading to a reorganization that created the First Baptist Church of Savannah. Fifty of Bryan’s adult members could read, having been taught the Bible and the Baptist Confession of Faith. First African Baptist established the first black led Sunday school for African Americans, and Henry Francis, who had been ordained by Bryan, operated a school for Georgia’s black children. (3)

Cultural Resistance: “Gimmee” That Old Time Religion!

Not all Africans and African Americans embraced Christianity, however. Some resisted by retaining their native African spiritual practices or their Islamic faith. Historians point out that a number of Africans who arrived in America were Muslims and that they never relinquished their faith in Islam.

There is relatively little historical documentation on eighteenth century enslaved Muslims in North America making discussion of them less conclusive than that about enslaved Africans who were Christians or who practiced indigenous traditional African religions. Some scholars believe that perhaps as many as 10% of Africans enslaved in North America between 1711 and 1715 were Muslims and that the majority probably were literate (Deeb 2002).

Islam was firmly established as a religion in Ancient Mali as early as the fourteenth century. As in other parts of the world, Islamic conversion occurred through trade and migration far more often than by force. In West Africa, prior to the eighteenth century, much of this conversion occurred through interaction of West Africans with Berber traders who controlled the trans-Saharan trade routes. From the early seventeenth century through the late eighteenth century, the influence of Islam spread among the people in many parts of the Senegambia region, the interior of Sierra Leone, the Gold Coast and as far south as the Bight of Benin.

According to historian Michael Gomez, the widespread influence of Islam in West Africa makes it highly likely that the numbers of Muslim Africans enslaved was probably in the thousands (1998:86). The recurrence of Muslim names among American-born Africans running away from enslavement in eighteenth century South Carolina offers some evidence of Muslim people’s presence and their efforts to continue their faith (Gomez 1998:60).

Historian Sylviane A. Diouf estimates at least 100,000 Africans brought to the Americas were Muslims, including political and religious leaders, traders, students, Islamic scholars, and judges. In some cases, these enslaved African Muslims were more educated than their American masters. According to Diouf, the captivity of several of the notable Muslim slaves who left narratives of their experiences grew out of complex religious, political, and social conflicts in West Africa after the disintegration of the Wolof Empire. Diouf argues, the religious principles and practices of African Muslims, including their literacy, made them resistant to enslavement and promoted their social differentiation from other enslaved Africans. As slaves, they were prohibited from reading and writing and had no ink or paper. Instead they used wood tablets and organic plant juices or stones to write with. Some wrote, in Arabic, verses of the Koran they knew by heart, so as not to forget how to write. According to Diouf, Arabic was used by slaves to plot revolts in Guyana, Rio de Janeiro and Santo Domingo because the language was not understood by slave owners. Manuscripts in Arabic of maps and blueprints for revolts also have been found in North America, Jamaica and Trinidad (Diouf 1998).

Diouf contends many enslaved Muslims went to great efforts to preserve the pillars of Islamic ritual because it allowed them “to impose a discipline on themselves rather than to submit to another people’s discipline” (1998:162). Diouf identifies references in the historical literature of slavery to the persistence of Islamic cultural practices among enslaved Muslims such as the wearing of turbans, beards, and protective rings; the use of prayer mats, beads, and talismans ( gris-gris ); and the persistence of Islamic dietary customs. For Diouf, saraka cakes cooked on Sapelo Island in Georgia were probably associated with sadakha or meritorious alms offered in the name of Allah. She speculates that the circular ring shout performed in Sea Island praise or prayer houses might have been a recreation of the Muslim custom of circumambulation of the Kaaba during the pilgrimage in Mecca. Arabic literacy, according to Diouf, generated powers of resistance because it served as a resource for spiritual inspiration and communal organization, “A tradition of defiance and rebellion (1998:145).”

Priests of African traditional religions also often continued to hold their beliefs. Even though over time the majority of Africans and African Americans became Christians, African Christianity and church rituals often incorporated African beliefs and rituals. Some scholars suggest that Africans readily acculturated to Christianity, especially those from West Central Africa, because of prior exposure to Christianity. Old ways died hard and some never died out. Historian John Thornton points out that none of the Christian movements in the Kongo brought about a radical break with Kongo religious or ideological past. Instead African Christianity simply emphasized already active tendencies in the worldview of the Kongo people (Thornton 1983:62–63).

Figure 5-4: Kongo Crucifix by Cliff1066 is licensed under CC BY 2.0 .Image of a seventeenth century crucifix made by Portuguese missionaries that combines the Kongo custom of using scepters and staffs as emblems of power with the representation of Christ as an African.

Figure 5-4: Kongo Crucifix by Cliff1066 is licensed under CC BY 2.0 .Image of a seventeenth century crucifix made by Portuguese missionaries that combines the Kongo custom of using scepters and staffs as emblems of power with the representation of Christ as an African.

One of the central beliefs of the Kongo, for example, emphasizes that human beings move through existence in counterclockwise circularity like the movement of the sun, coming into life or waking up in the east, grow to maturity reaching the height of their powers in the north, die and pass out of life in the west into life after death in the south then come back in the east being born again (Fu-Kiah 1969; Thompson 1984; McGaffey 1986). Many West African groups believe in life after death and some believes that people are reborn in their descendants. These ideas, although in a different context, blended well with Christian beliefs in life after death and with the Christian belief being born again. 3