10.2: Politics of Reconstruction

- Page ID

- 45974

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Reconstruction

Politics of Reconstruction

Reconstruction—the effort to restore southern states to the Union and to redefine African Americans’ place in American society—began before the Civil War ended. President Abraham Lincoln began planning for the reunification of the United States in the fall of 1863. With a sense that Union victory was imminent and that he could turn the tide of the war by stoking Unionist support in the Confederate states, Lincoln issued a proclamation allowing Southerners to take an oath of allegiance. When just ten percent of a state’s voting population had taken such an oath, loyal Unionists could then establish governments. These so-called Lincoln governments sprang up in pockets where Union support existed like Louisiana, Tennessee, and Arkansas. Unsurprisingly, these were also the places that were exempted from the liberating effects of the Emancipation Proclamation.

Initially proposed as a war aim, Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation committed the United States to the abolition of slavery. However, the Proclamation freed only slaves in areas of rebellion and left more than 700,000 in bondage in Delaware, Kentucky, Maryland, and Missouri as well as Union-occupied areas of Louisiana, Tennessee, and Virginia.

To cement the abolition of slavery, Congress passed the Thirteenth Amendment on January 31, 1865. The amendment and legally abolished slavery “except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted.” Section Two of the amendment granted Congress the “power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.” State ratification followed, and by the end of the year the requisite three-fourths states had approved the amendment, and four million people were forever free from the slavery that had existed in North America for 250 years.

Lincoln’s policy was lenient, conservative, and short-lived. Reconstruction changed when John Wilkes Booth shot Lincoln on April 14, 1865, during a performance of “Our American Cousin” at the Ford Theater. Treated rapidly and with all possible care, Lincoln succumbed to his wounds the following morning, leaving a somber pall over the North and especially among African Americans.

The assassination of Abraham Lincoln propelled Vice President Andrew Johnson into the executive office in April 1865. Johnson, a states’ rights, strict-constructionist and unapologetic racist from Tennessee, offered southern states a quick restoration into the Union. His Reconstruction plan required provisional southern governments to void their ordinances of secession, repudiate their Confederate debts, and ratify the Thirteenth Amendment. On all other matters, the conventions could do what they wanted with no federal interference. He pardoned all Southerners engaged in the rebellion with the exception of wealthy planters who possessed more than $20,000 in property. The southern aristocracy would have to appeal to Johnson for individual pardons. In the meantime, Johnson hoped that a new class of Southerners would replace the extremely wealthy in leadership positions.

Many southern governments enacted legislation that reestablished antebellum power relationships. South Carolina and Mississippi passed laws known as Black Codes to regulate black behavior and impose social and economic control. These laws granted some rights to African Americans, like the right to own property, to marry or to make contracts. But they also denied fundamental rights. White lawmakers forbade black men from serving on juries or in state militias, refused to recognize black testimony against white people, apprenticed orphan children to their former masters, and established severe vagrancy laws. Mississippi’s vagrant law required all freedmen to carry papers proving they had means of employment. If they had no proof, they could be arrested and fined. If they could not pay the fine, the sheriff had the right to hire out his prisoner to anyone who was willing to pay the tax. Similar ambiguous vagrancy laws throughout the South reasserted control over black labor in what one scholar has called “slavery by another name.” Black codes effectively criminalized black leisure, limited their mobility, and locked many into exploitative farming contracts. Attempts to restore the antebellum economic order largely succeeded.

These laws and outrageous mob violence against black southerners led Republicans to call for a more dramatic Reconstruction. So when Johnson announced that the southern states had been restored, congressional Republicans refused to seat delegates from the newly reconstructed states.

Republicans in Congress responded with a spate of legislation aimed at protecting freedmen and restructuring political relations in the South. Many Republicans were keen to grant voting rights for freed men in order to build a new powerful voting bloc. Some Republicans, like United States Congressman Thaddeus Stevens, believed in racial equality, but the majority were motivated primarily by the interest of their political party. The only way to protect Republican interests in the South was to give the vote to the hundreds of thousands of black men. Republicans in Congress responded to the codes with the Civil Rights Act of 1866, the first federal attempt to constitutionally define all American-born residents (except Native peoples) as citizens. The law also prohibited any curtailment of citizens’ “fundamental rights.”

The Fourteenth Amendment developed concurrently with the Civil Rights Act to ensure its constitutionality. The House of Representatives approved the Fourteenth Amendment on June 13, 1866. Section One granted citizenship and repealed the Taney Court’s infamous Dred Scott (1857) decision. Moreover, it ensured that state laws could not deny due process or discriminate against particular groups of people. The Fourteenth Amendment signaled the federal government’s willingness to enforce the Bill of Rights over the authority of the states.

Based on his belief that African Americans did not deserve rights, President Johnson opposed both the passage of the Fourteenth Amendment and vetoed the Civil Rights Act, as he believed black Americans did not deserve citizenship. With a two-thirds majority gained in the 1866 midterm elections, Republicans overrode the veto, and in 1867, they passed the first of two Reconstruction Acts, which dissolved state governments and divided the South into five military districts. Before states could rejoin the Union, they would have to ratify the Fourteenth Amendment, write new constitutions enfranchising African Americans, and abolish black codes. The Fourteenth Amendment was finally ratified on July 9, 1868.

In the 1868 Presidential election, former Union General Ulysses S. Grant ran on a platform that proclaimed, “Let Us Have Peace” in which he promised to protect the new status quo. On the other hand, the Democratic candidate, Horatio Seymour, promised to repeal Reconstruction. Black Southern voters helped Grant him win most of the former Confederacy.

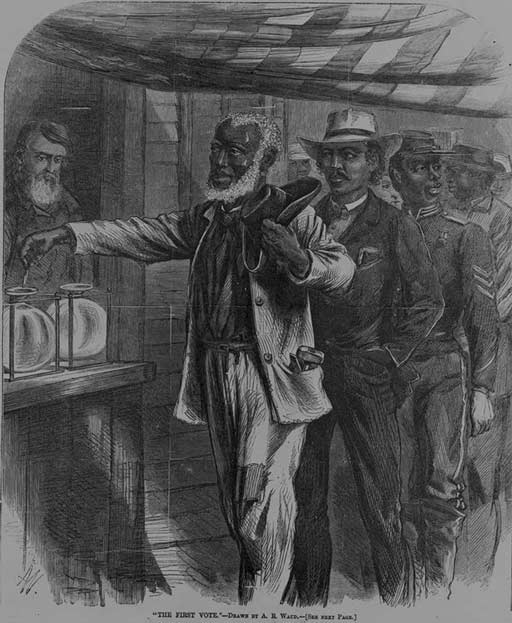

Reconstruction brought the first moment of mass democratic participation for African Americans. In 1860, only five states in the North allowed African Americans to vote on equal terms with whites. Yet after 1867, when Congress ordered Southern states to eliminate racial discrimination in voting, African Americans began to win elections across the South. In a short time, the South was transformed from an all-white, pro-slavery, Democratic stronghold to a collection of Republican-led states with African Americans in positions of power for the first time in American history.

Through the provisions of the Congressional Reconstruction Acts, black men voted in large numbers and also served as delegates to the state constitutional conventions in 1868. Black delegates actively participated in revising state constitutions. One of the most significant accomplishments of these conventions was the establishment of a public school system. While public schools were virtually nonexistent in the antebellum period, by the end of Reconstruction, every Southern state had established a public school system. Republican officials opened state institutions like mental asylums, hospitals, orphanages, and prisons to white and black residents, though often on a segregated basis. They actively sought industrial development, northern investment, and internal improvements.

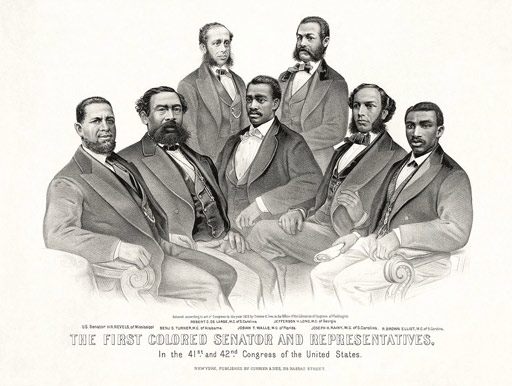

African Americans served at every level of government during Reconstruction. At the federal level, Hiram Revels and Blanche K. Bruce were chosen as United States Senators from Mississippi. Fourteen men served in the House of Representatives. At least two hundred seventy other African American men served in patronage positions as postmasters, customs officials, assessors, and ambassadors. At the state level, more than 1,000 African American men held offices in the South. P. B. S. Pinchback served as Louisiana’s Governor for thirty-four days after the previous governor was suspended during impeachment proceedings and was the only African American state governor until Virginia elected L. Douglass Wilder in 1989. Almost 800 African American men served as state legislators around the South with African Americans at one time making up a majority in the South Carolina House of Representatives.

African American office holders came from diverse backgrounds. Many had been born free or had gained their freedom before the Civil War. Many free African Americans, particularly those in South Carolina, Virginia, and Louisiana, were wealthy and well educated, two facts that distinguished them from much of the white population both before and after the Civil War. Some like Antione Dubuclet of Louisiana and William Breedlove from Virginia owned slaves before the Civil War. Others had helped slaves escape or taught them to read like Georgia’s James D. Porter.

The majority of African American office holders, however, gained their freedom during the war. Among them were skilled craftsman like Emanuel Fortune, a shoemaker from Florida, minsters such as James D. Lynch from Mississippi, and teachers like William V. Turner from Alabama. Moving into political office was a natural continuation of the leadership roles they had held in their former slave communities.

By the end of Reconstruction in 1877, more than 2,000 African American men had served in offices ranging from mundane positions such as local Levee Commissioner to United States Senator. When the end of Reconstruction returned white Democrats to power in the South, all but a few African American office holders lost their positions. After Reconstruction, African Americans did not enter the political arena again in large numbers until well into the twentieth century. (2)

The Meaning of Black Freedom

Land was one of the major desires of the freed people. Frustrated by responsibility for the growing numbers of freed people following his troops, General William T. Sherman issued Special Field Order No. 15 in which land in Georgia and South Carolina was to be set aside as a homestead for the freedpeople. Sherman lacked the authority to confiscate and distribute land, so this plan never fully took effect. One of the main purposes of the Freedmen’s Bureau, however, was to redistribute lands to former slaves that had been abandoned and confiscated by the federal government. Even these land grants were short lived. In 1866, land that ex-Confederates had left behind was reinstated to them.

Freedpeople’s hopes of land reform were unceremoniously dashed as Freedmen’s Bureau agents held meetings with the freedmen throughout the South, telling them the promise of land was not going to be honored and that instead they should plan to go back to work for their former owners as wage laborers. The policy reversal came as quite a shock. In one instance, Freedmen’s Bureau Commissioner General Oliver O. Howard went to Edisto Island to inform the black population there of the policy change. The black commission’s response was that “we were promised Homesteads by the government… You ask us to forgive the land owners of our island…The man who tied me to a tree and gave me 39 lashes and who stripped and flogged my mother and my sister… that man I cannot well forgive. Does it look as if he has forgiven me, seeing how he tries to keep me in a condition of helplessness?”

In working to ensure that crops would be harvested, agents sometimes coerced former slaves into signing contracts with their former masters. However, the Bureau also instituted courts where African Americans could seek redress if their employers were abusing them or not paying them. The last ember of hope for land redistribution was extinguished when Thaddeus Stevens and Charles Sumner’s proposed land reform bills were tabled in Congress. Radicalism had its limits, and the Republican Party’s commitment to economic stability eclipsed their interest in racial justice.

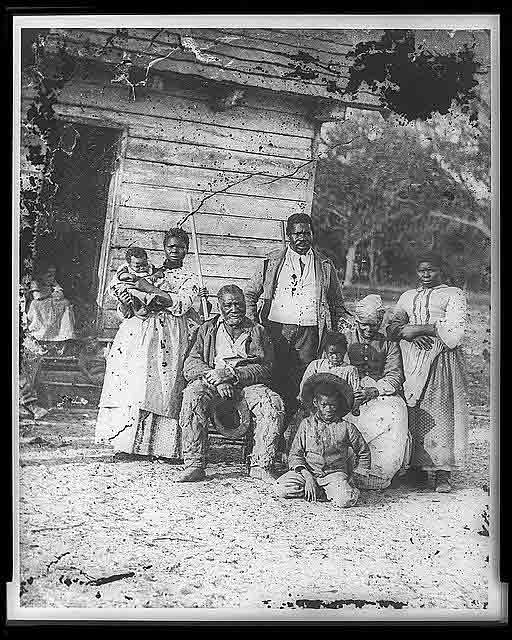

Another aspect of the pursuit of freedom was the reconstitution of families. Many freedpeople immediately left plantations in search of family members who had been sold away. Newspaper ads sought information about long lost relatives. People placed these ads until the turn of the 20 thcentury, demonstrating the enduring pursuit of family reunification. Freedpeople sought to gain control over their own children or other children who had been apprenticed to white masters either during the war or as a result of the Black Codes. Above all, freedpeople wanted freedom to control their families.

Many freedpeople rushed to solemnize unions with formal wedding ceremonies. Black people’s desires to marry fit the government’s goal to make free black men responsible for their own households and to prevent black women and children from becoming dependent on the government.

Freedpeople placed a great emphasis on education for their children and themselves. For many, the ability to finally read the Bible for themselves induced work-weary men and women to spend all evening or Sunday attending night school or Sunday school classes. It was not uncommon to find a one-room school with more than 50 students ranging in age from 3 to 80. As Booker T. Washington famously described the situation, “it was a whole race trying to go to school. Few were too young, and none too old, to make the attempt to learn.”

Many churches served as schoolhouses and as a result became central to the freedom struggle. Free and freed black southerners carried well-formed political and organizational skills into freedom. They developed anti-racist politics and organizational skills through anti-slavery organizations turned church associations. Liberated from white-controlled churches, black Americans remade their religious worlds according to their own social and spiritual desires.

One of the more marked transformations that took place after emancipation was the proliferation of independent black churches and church associations. In the 1930s, nearly 40% of 663 black churches surveyed had their organizational roots in the post-emancipation era. Many independent black churches emerged in the rural areas and most of them had never been affiliated with white churches.

Many of these independent churches were quickly organized into regional, state, and even national associations, often by brigades of northern and midwestern free blacks who went to the South to help the freedmen. Through associations like the Virginia Baptist State Convention and the Consolidated American Baptist Missionary Convention, Baptists became the fastest growing post-emancipation denomination, building on their anti-slavery associational roots and carrying on the struggle for black political participation.

Tensions between Northerners and Southerners over styles of worship and educational requirements strained these associations. Southern, rural black churches preferred worship services with more emphasis on inspired preaching, while northern urban blacks favored more orderly worship and an educated ministry.

Perhaps the most significant internal transformation in churches had to do with the role of women—a situation that eventually would lead to the development of independent women’s conventions in Baptist, Methodist and Pentecostal churches. Women like Nannie Helen Burroughs and Virginia Broughton, leaders of the Baptist Woman’s Convention, worked to protect black women from sexual violence from white men. Black representatives repeatedly articulated this concern in state constitutional conventions early in the Reconstruction era. In churches, women continued to fight for equal treatment and access to the pulpit as preachers, even though they were able to vote in church meetings.

Black churches provided centralized leadership and organization in post-emancipation communities. Many political leaders and officeholders were ministers. Churches were often the largest building in town and served as community centers. Access to pulpits and growing congregations, provided a foundation for ministers’ political leadership. Groups like the Union League, militias and fraternal organizations all used the regalia, ritual and even hymns of churches to inform and shape their practice.

Black Churches provided space for conflict over gender roles, cultural values, practices, norms, and political engagement. With the rise of Jim Crow, black churches would enter a new phase of negotiating relationships within the community and the wider world. (2)

Reconstruction and Women

Reconstruction involved more than the meaning of emancipation. Women also sought to redefine their roles within the nation and in their local communities. The abolitionist and women’s rights movements simultaneously converged and began to clash. In the South, both black and white women struggled to make sense of a world of death and change. In Reconstruction, leading women’s rights advocate Elizabeth Cady Stanton saw an unprecedented opportunity for disenfranchised groups. Women as well as black Americans, North and South could seize political rights. Stanton formed the Women’s Loyal National League in 1863, which petitioned Congress for a constitutional amendment abolishing slavery. The Thirteenth Amendment marked a victory not only for the antislavery cause, but also for the Loyal League, proving women’s political efficacy and the possibility for radical change. Now, as Congress debated the meanings of freedom, equality, and citizenship for former slaves, women’s rights leaders saw an opening to advance transformations in women’s status, too. On the tenth of May 1866, just one year after the war, the Eleventh National Women’s Rights Convention met in New York City to discuss what many agreed was an extraordinary moment, full of promise for fundamental social change. Elizabeth Cady Stanton presided over the meeting. Also in attendance were prominent abolitionists with whom Stanton and other women’s rights leaders had joined forces in the years leading up to the war. Addressing this crowd of social reformers, Stanton captured the radical spirit of the hour: “now in the reconstruction,” she declared, “is the opportunity, perhaps for the century, to base our government on the broad principle of equal rights for all.” Stanton chose her universal language—“equal rights for all”—with intention, setting an agenda of universal suffrage. Thus, in 1866, the National Women’s Rights Convention officially merged with the American Antislavery Society to form the American Equal Rights Association (AERA). This union marked the culmination of the longstanding partnership between abolitionist and women’s rights advocates.

The AERA was split over whether black male suffrage should take precedence over universal suffrage, given the political climate of the South. Some worried that political support for freedmen would be undermined by the pursuit of women’s suffrage. For example, AERA member Frederick Douglass insisted that the ballot was literally a “question of life and death” for southern black men, but not for women. Some African-American women challenged white suffragists in other ways. Frances Harper, for example, a free-born black woman living in Ohio, urged them to consider their own privilege as white and middle class. Universal suffrage, she argued, would not so clearly address the complex difficulties posed by racial, economic, and gender inequality.

These divisions came to a head early in 1867, as the AERA organized a campaign in Kansas to determine the fate of black and woman suffrage. Elizabeth Cady Stanton and her partner in the movement, Susan B. Anthony, made the journey to advocate universal suffrage. Yet they soon realized that their allies were distancing themselves from women’s suffrage in order to advance black enfranchisement. Disheartened, Stanton and Anthony allied instead with white supremacists that supported women’s equality. Many fellow activists were dismayed by Stanton and Anthony’s willingness to appeal to racism to advance their cause.

These tensions finally erupted over conflicting views of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments. Women’s rights leaders vigorously protested the Fourteenth Amendment. Although it established national citizenship for all persons born or naturalized in the United States, the amendment also introduced the word “male” into the Constitution for the first time. After the Fifteenth Amendment ignored “sex” as an unlawful barrier to suffrage, an omission that appalled Stanton, the AERA officially dissolved. Stanton and Anthony formed the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA), while those suffragists who supported the Fifteenth Amendment, regardless of its limitations, founded the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA).

The NWSA soon rallied around a new strategy: the ‘New Departure’. This new approach interpreted the Constitution as already guaranteeing women the right to vote. They argued that by nationalizing citizenship for all persons, and protecting all rights of citizens—including the right to vote—the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments guaranteed women’s suffrage.

Broadcasting the New Departure, the NWSA encouraged women to register to vote, which roughly seven hundred did between 1868 and 1872. Susan B. Anthony was one of them and was arrested but then acquitted in trial. In 1875, the Supreme Court addressed this constitutional argument: acknowledging women’s citizenship, but arguing that suffrage was not a right guaranteed to all citizens. This ruling not only defeated the New Departure, but also coincided with the Court’s broader reactionary interpretation of the Reconstruction Amendments that significantly limited freedmen’s rights. Following this defeat, many suffragists like Stanton increasingly replaced the ideal of ‘universal suffrage’ with arguments about the virtue that white women would bring to the polls. These new arguments often hinged on racism and declared the necessity of white women voters to keep black men in check.

Advocates for women’s suffrage were largely confined to the North, but southern women were experiencing social transformations as well. The lines between refined white womanhood and degraded enslaved black femaleness were no longer so clearly defined. Moreover, during the war, southern white women had been called upon to do traditional man’s work, chopping wood and managing businesses. While white southern women decided whether and how to return to their prior status, African American women embraced new freedoms and a redefinition of womanhood.

Southern black women sought to redefine their public and private lives. Their efforts to control their labor met the immediate opposition of southern white women. Gertrude Clanton, a plantation mistress before the war, disliked cooking and washing dishes, so she hired an African American woman to do the washing. A misunderstanding quickly developed. The laundress, nameless in Gertrude’s records, performed her job and returned home. Gertrude believed that her money had purchased a day’s labor, not just the load of washing, and she became quite frustrated. Meanwhile, this washerwoman and others like her set wages and hours for themselves, and in many cases began to take washing into their own homes in order to avoid the surveillance of white women and the sexual threat posed by white men.

Similar conflicts raged across the South. White Southerners demanded that African American women work in the plantation home and instituted apprenticeship systems to place African American children in unpaid labor positions. African American women combated these attempts by refusing to work at jobs without fair pay or fair conditions and by clinging tightly to their children.

African American women formed clubs to bury their dead, to celebrate African American masculinity, and to provide aid to their communities. On May 1, 1865, African Americans in Charleston created the precursor to the modern Memorial Day by mourning the Union dead buried hastily on a race track-turned prison. Like their white counterparts, the 300 African American women who participated had been members of the local Patriotic Association, which aided freed people during the war. African American women continued participating in Federal Decoration Day ceremonies and, later, formed their own club organizations. Racial violence, whether city riots or rural vigilantes, continued to threaten these vulnerable households. Nevertheless, the formation and preservation of African American households became a paramount goal for African American women. (2)

- The American YAWP. Provided by: Stanford University Press. Located at: http://www.americanyawp.com/index.html. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

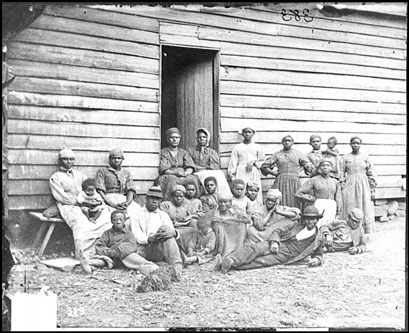

- CUMBERLAND LANDING, VA. GROUP OF 'CONTRABANDS' AT FOLLER'S HOUSE. Authored by: James F. Gibson. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cumberland_Landing,_Va._Group_of_%27contrabands%27_at_Foller%27s_house_LOC_cwpb.01005.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- THE FIRST VOTE. Authored by: Alfred R. Waud. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_First_Vote.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- FIRST COLORED SENATOR AND REPRESENTATIVES. Authored by: Currier and Ives. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:First_Colored_Senator_and_Representatives.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- FAMILY OF AFRICAN AMERICAN SLAVES ON SMITH'S PLANTATION BEAUFORT SOUTH CAROLINA. Authored by: Timothy O'Sullivan. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Family_of_African_American_slaves_on_Smith%27s_Plantation_Beaufort_South_Carolina.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- GLIMPSES AT THE FREEDMEN. Authored by: Jas. E. Taylor . Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Glimpses_at_the_Freedmen_-_The_Freedmen%27s_Union_Industrial_School,_Richmond,_Va._-_from_a_sketch_by_Jas_E._Taylor._LCCN98501491.tif. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- AFRICAN AMERICANS STANDING OUTSIDE OF A CHURCH. Authored by: unknown photographer, prepared by W. E. B. DuBois. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:African_Americans_standing_outside_of_a_church_LCCN99472379.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright