4.2: African Americans and the Rhetoric of Revolution

- Page ID

- 45943

African Americans and the American Revolution

African Americans and the Rhetoric of Revolution

Thomas Jefferson, and other leaders of the Revolution, studied and borrowed ideas of natural rights from European Enlightenment philosophers such as John Locke. They then incorporated natural rights theory into documents like the Declaration of Independence that not only justified the Revolution but served, in Jefferson’s words, as “an expression of the American mind.” Natural rights, such as the right to be free and pursue one’s own “happiness,” are rights all human beings possess that are not granted by government and cannot be revoked or repealed. As it says in the preamble to the Declaration of Independence, natural rights are “truths” that are “self-evident” and “unalienable” such as “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

How could a group of people feel so passionate about these unalienable rights, yet maintain the brutal practice of human bondage? Somehow slavery would manage to survive the revolutionary era despite fervent arguments about its incompatibility with the new nation’s founding ideals.(5) Nevertheless, black people in particular seized on the rhetoric of the American Revolution to highlight the contradiction between the colonists’ cries for freedom and liberty from British oppression and the existence of racial slavery in the colonies. (1)

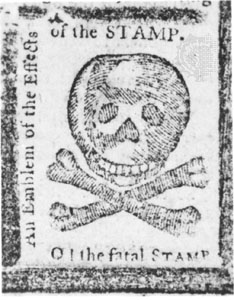

African Americans, both slave and free, immediately jumped into the fray when white colonists began to protest British colonial rule for the first time in 1765 in response to the Stamp Act, which imposed a tax on newspapers, pamphlets, and legal documents. Many colonists viewed the act as an arbitrary tax designed only to generate revenue to pay down debt Britain accrued during the French and Indian War, which colonists helped the British win in the 1750s and 1760s. Colonists also resented that this tax was imposed on them without having a voice in Parliament, which led to cries of “No taxation without representation!”

In Charleston, South Carolina, slaves saw white protesters take to the streets and chant, “Liberty! Liberty! And stamp’d paper.” The issue of taxation, of course, mattered far less to slaves than the language whites used in their protests. Soon after Charleston’s white residents protested the Stamp Act, some of the city’s slaves responded with their own chants of “Liberty! Liberty!,” which shocked and frightened white residents. “If most slaves were illiterate,” writes historian David Brian Davis, “white leaders knew or soon discovered that the slaves’ networks of communication passed on every kind of news almost as quickly as horses could gallop.” (Davis, 2006, p.144–146)

African Americans, and some whites opposed to slavery, also recognized the curious irony of statements made by some white colonists that characterized British policies as a conspiracy that threatened to turn free white people into “slaves,” that is, people lacking the same rights and liberties as British citizens overseas. In 1774, George Washington characterized the plight of colonists under British rule as analogous to that of black slaves ruled over by white slaves masters like himself. Writing after Parliament passed the Intolerable Acts to punish rebellious colonists for the Boston Tea Party, Washington said, “the crisis is arrived when we must assert our rights, or submit to every imposition, that can be heaped upon us, till custom and use shall make us tame and abject slaves, as the blacks we rule over with such arbitrary sway.” (Jordan, 1968, p. 262)

At the time, Washington was a political leader in Virginia and the master of a large plantation along the Potomac River, Mt. Vernon, where he personally owned more than one hundred slaves. In the late 1760s, the famous Philadelphia physician, Benjamin Rush, wrote a correspondent in France about how the Revolution’s rhetoric of liberty and freedom, and the potential for enslavement or servitude, forced American colonists to reckon with the hypocrisy of fighting for liberty and rights while countenancing racial slavery. “It would be useless for us to denounce the servitude to which the Parliament of Great Britain wishes to reduce us, while we continue to keep our fellow creatures in slavery just because their color is different from ours.” (Davis, 2006, p. 145).

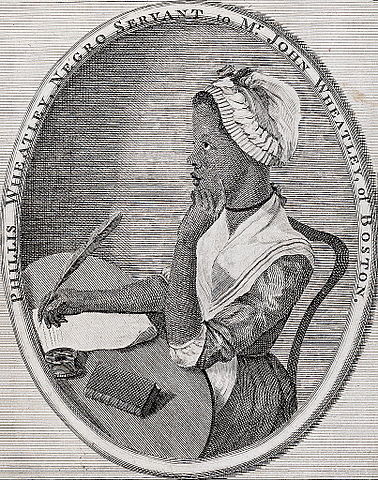

In 1773, Phyllis Wheatley, an eighteen-year-old poet who had been born in West Africa but now lived as a slave in Massachusetts, reflected on the same contradictions Rush highlighted a few years earlier. “In every human Breast, God has implanted a Principle, which we call Love of Freedom,” Wheatley wrote. How then can white colonists reconcile the “Cry of Liberty” with the “Exercise of Oppressive Power over others?” (Carson, Lapansky-Werner & Nash, 2019, p. 94)

That same year, which saw a record number of antislavery pamphlets published and sermons given in the America colonies, a slave named Felix sent a freedom petition on behalf of himself and other slaves in Massachusetts to the colonial governor and legislature. Freedom petitions, or freedom suits, had existed in the American colonies since the late 1600s and allowed slaves to ask courts or legislatures to free them from bondage on the basis of legal violations. While a small number of slaves petitioned courts for their freedom, the number of petitions rose during the American Revolution. In his petition, Felix argued that slavery left black people in bondage for life without the hope of acquiring property and freedom for themselves or their progeny. No matter how devoted slaves were to their masters “neither they, nor their Children to all Generations, shall ever be able to do so, or to possess and enjoy any Thing, no, not even Life itself, but in a Manner as the Beasts that perish.” Since the law deprived slaves of property and instead made them into property, their condition resembled that of an animal and not a human being. This was a violation of natural rights. “Relief” from the legislature of Massachusetts that would not harm their masters, and free them from slavery, would be “to us… as Life from the dead.” (Davis, 2006, p. 146)

Black Americans continued to petition for their freedom during the Revolutionary War, which broke out in 1775 in Massachusetts, while others free blacks protested on behalf of the enslaved by highlighting the contradictions between a war fought for freedom and the persistence of slavery. In 1777, a former slave, named Prince Hall, declared that the ideals Americans fought for “in the course of their unhappy difficulties with Great Britain pleads stronger than a thousand arguments… [that black people] may be restored to the enjoyments of that which is the natural right of all men.” (Carson, Lapansky-Werner & Nash, 2019, p. 94). Two years earlier, Hall founded the first African American branch of Freemasonry and started the first black Masonic Lodge in Boston. (1)

Thomas Jefferson

No one embodied the contradictions that lay at the heart of the Revolution’s rhetoric more than Thomas Jefferson. Like George Washington, Jefferson was part of Virginia’s slaveholding aristocracy. Slavery afforded Jefferson the opportunity and freedom to pursue a career as a lawyer and political leader in Virginia before and during the American Revolution. When the Revolution broke out, Jefferson owned just under 200 slaves on his central Virginia plantation, Monticello. As a student of the European Enlightenment, and a scholar of treatises on natural rights written by Enlightenment philosophers such as John Locke, Jefferson saw slavery as a regrettable institution and hoped a process of gradual emancipation would eventually lead to its permanent demise.

When Jefferson wrote the Declaration of Independence in the summer of 1776, he used the language of natural rights to justify the revolution and, in so doing, composed some of the most important, and potentially radical, words in American history that carried anti-slavery overtones:

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that there are endowed by the Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness. (US, 1776)

Since he was writing about natural rights, and not political or civil rights, Jefferson saw this equality and desire for freedom and “happiness” (i.e. property) as applying to all people, even Africans and African Americans. Jefferson made this belief clear in a passage he wrote in an early draft of the Declaration that was eventually removed because it threatened the support of the states of South Carolina and Georgia in the cause of independence. In this passage, Jefferson blamed the African slave trade and slavery on King George rather than on colonial slaveholders like himself. King George, he argued, “has waged cruel war against human nature itself, violating the most sacred rights of life & liberty in the persons of a distant people [i.e. Africans] who never offended him, captivating & carrying them into slavery in another hemisphere, or to incur miserable death in their transportation thither.” (Davis, 2006, p. 146)

Despite Jefferson’s recognition that slavery violated the natural rights of Africans and African Americans, he only freed a very small number of his slaves during his life and left hundreds still in bondage at his death in 1826. After the Revolution, Jefferson recognized that an explanation was in order. How could the author of the Declaration of Independence, one of the most eloquent statements of the natural rights of all people, not free his own slaves or advocate for the immediate abolition of slavery? Jefferson wrote his explanation in his only published book, Notes on the State of Virginia (1782). In Jefferson’s mind, abolition carried grave threats and risks to the young United States. He envisioned an apocalyptic race war in which former slaves would slaughter former slave owners out of revenge. He also borrowed pseudo-scientific racist ideas from the European Enlightenment that argued that Africans were inferior to Europeans, particularly in terms of intellectual capacities, which made them unfit as citizens.

“Deep rooted prejudices entertained by the whites; ten thousand recollections, by the blacks, of the injuries they have sustained; new provocations; the real distinctions which nature has made; and many other circumstances, will divide us into parties, and produce convulsions which will probably never end but in the extermination of the one or the other race,” Jefferson wrote.

He also feared racial “mixture” and the corruption of white racial purity, despite maintaining a sexual relationship with his slave, Sally Hemings, a woman who bore him five children and who herself was the product of a sexual encounter between Jefferson’s father-in-law and Hemings’s mother, Betty. Jefferson still hoped emancipation would happen at some distant date in the future and when it occurred all former slaves will have to be “removed beyond the reach of mixture.” For Jefferson, the author of the Declaration of Independence, eventual emancipation could only occur with a plan for the colonization of African Americans outside of the United States where they could have their own country separate from white Americans. (1)

- Authored by: Florida State College at Jacksonville. License: CC BY: Attribution

- U.S. History. Provided by: The Independence Hall Association. Located at: http://www.ushistory.org/us/index.asp. License: CC BY: Attribution

- O! the fatal stamp. Provided by: Pennsylvania Journal. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:O!_the_fatal_Stamp.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- The Washington Family. Authored by: Edward Savage. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_Washington_Family_by_Edward_Savage_1798.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Phyllis Wheatley frontispiece. Authored by: Scipio Moorhead. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Phillis_Wheatley_frontispiece.jpg. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- A Philosophic Cock. Authored by: James Akin. Located at: commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cock_ca1804_attrib_to_JamesAkin_AmericanAntiquarianSociety.png. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright