5.0: Introduction

- Page ID

- 56934

Having looked at the general idea of technical writing, the relationship of technical writing to the user, the visual communication angle of technical writing, and the process of document design in tech writing, we next need to cover a major pillar of technical writing in the minds of many: genres. (This is the part where we talk about report writing).

When we work in genres, we’re working in what are essentially categories of texts that have formed over time to mean something. We often run into genre when it comers to books and television, with some books or shows (or films) labeled with categories like “Suspense” or “Mystery” or “Comedy.” We can also get much more specific, especially in television where the are very well-worn genres that have appeared over time, so you might run into a “police procedural,” a very specific type of show. In the case of police procedural, you have a show that is entirely about the process of the police investigating a particular crime. The genre gives you a clue as to the general type of show or film you’re going to watch. (Bear with me in this discussion—you may wonder why I’m talking about TV, but I promise it will all wrap back around in a useful way in a bit).

Genre, however, is not specific to the point that it controls everything about a production: genre is fluid and changes over time. For example, the police procedural of the earlier years of television with shows like Dragnet did not have a major relationship component to the show—it was just about the crime for the most part. However, if you made a police procedural today without heavy interaction between different leads and ongoing stories about the police and their lives, you’d likely have a flop on your hands. The genre has evolved and expectations have changed.

Many genres come with an expectation even that you’ll have a sub-genre that will come into play to flavor the dominant genre. Think about police procedurals again—you have shows that are much more direct and serious like the various iterations of behemoths like Law & Order and then you have shows much more playful at times such as Castle or even shows that skirt further towards the edge of the genre (if they belong there at all) like Psych (A true gem of television, up there with Star Trek: Deep Space Nine, Midsomer Murders, and Fringe). In these cases, there is a general approach to the genre, but all of that is filtered through the general gist of the sub-genre, such as comedy. With very common genres like the police procedural we often judge these shows on how they take the genre constraints and then push them or subvert them with a secondary genre or a new approach. Very few shows gain success for being an ideal procedural—it’s all about what they do beyond that framework that gets folks excited. Sorry Dragnet.

Now, let’s bring this back home—all of what I’ve said applies to technical writing genres. When we think about a genre like a report, that term is just like a genre in television like a police procedural. The term itself gives you a general idea of what the document you’re going to create might look like, but for the most part it is utterly meaningless if you’re expecting the genre to give you a detailed insight into what your report should look like. Just like the television examples, the technical writing genres are not laws carved into the bedrock of reality—they are categories, fluid ones at that, that give you a general gist of the type of document you’ll be making without really getting into the specifics of things.

Asking someone to teach you how to write a report or any other genre in the specific sense of what steps to take and what sections to include is akin to asking someone to teach you how to make a police procedural—they can give you a general sense of the expectations and permutations of the genre in a broad and classic sense, but they cannot tell you exactly how to write it. And, to go even further and hammer this point home, if I was to tell you how to write a report it would be at best a polite fiction. My idea of a report and your future employers’ idea of a report would differ, and even the types of reports you’d write within the same organization would change over time. There is no secret bastion of knowledge where you can uncover the true secrets of writing the ultimate report, no secret recipe to follow for success across time and space. And to be clear, anyone who tells you different isn’t being very honest. So, what are we left with? We are left with research. Imagine that. Didn’t see that coming, did you? :)

Genre work, just like any other part of technical writing, relies on research to get things right. Report writing, white paper writing, grant/proposal writing, technical description writing, and any other type of genre you’d want to associate with professional or technical writing will always rely on the context that you’re writing in and the expectations that surround you. That isn’t to say that having a general sense of a genre is useless—it isn’t at all! You need to know the general sense of the genre just to orient yourself and help identify it. But, expecting a general sense of the genre to guide you from start to finish is expecting too much from too little.

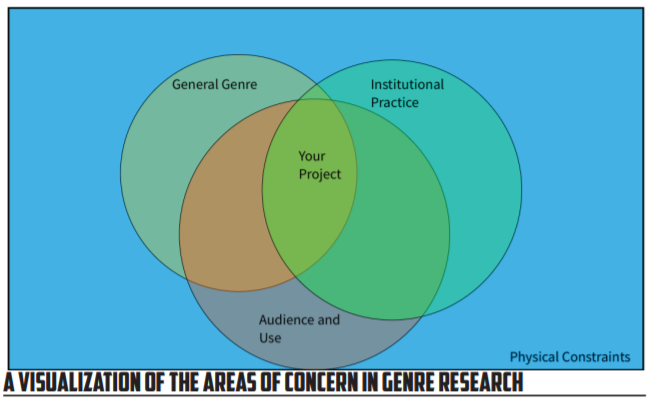

When you operate within an organizational context and you’re writing a genre like a white paper or a report, you’re often writing within a series of constraints that will guide your work. On one level, you have the general gist of the genre that will be guiding what is going on. Unless your organization likes to call things odd names (my niece, for example, used to call buzzards “pelican badgers” for reasons unknown to anyone), the general genre constraints will apply. At the same time, the formal history of the genre within your organization will come into play—how have people done this in the past, and how do they do it now? In addition, the physical format of your genre will impact what you do (is it a template, or is it something that you have more control over?). Finally, the audience and use of the document will come to play as well. This confluence of forces will shape the final format of your text, and unless your workplace has very strict rules on such things (and some do, I’ll freely admit) there will be some movement between documents as to what the genre looks like and does.

When you think about researching your work in a genre, realize that each of these elements will play into the others to create a final version of your genre. In some cases one element may be more dominant—for example you may have a use or audience that is hyper-specific, such as a federal grant that asks for a series of employment documents and professional assessments of your project by subject-matter experts (such as an archival expert if you’re getting funds to preserve an artifact or archive). You might also have an audience that is extremely formal or informal that will impact how you write, which may clash with your institution’s existing culture—it gets tricky fast. Below you’ll see the confluence of all of this mapped in a visual form for those that prefer to see rather than to read:

In each case, you’ll want to query the general genre, the institutional practice, and the audience and use of your text to get an idea of what needs to be done.

For the rest of this chapter, we’ll break down the discussion of genre into two major bits of content: we’ll cover the general questions of research you need to carry out work on any particular genre situation, and we’ll go through a top-level overview of a few genres and what you can generally expect in those genres. The real heart of the chapter will be the discussion of the research questions—they will be your guide in virtually any genre-dependent situation. The coverage of the various genres at the top level will supplement this by giving you an idea of what genres you might be called on to write and some general (subject to context) tips you might want to know when you’re writing in those genres.