1.4: Signposting and Taxonomy

- Page ID

- 50681

Signposting and Taxonomy

For our final subject in Chapter 1, I want to mention a crucial duo central to effective technical writing: signposting and taxonomy. These two subjects are closely related, in that signposting relies on a taxonomy of sorts to operate, and is an expression of taxonomy, but they are worth treating individually as well as jointly. In a nutshell, these two tools are used to shape your text so that it has a definite structure that can be seen, ideally, at a glance. We’ll get more into the idea of taxonomy a bit later in the text, and in many ways the Cardsorting resource in the back of the text is entirely about these two subjects, viewed through the lens of potential users. We’ll look at signposting first before moving to taxonomy and then back between the two.

Basic Textual Signposting

Signposting is at its core telling your reader what is happening in your text. This signposting happens at two different levels, and both are important to readers in their own ways. The first way that signposting happens is via the text itself. When you use terms like “firstly,” “second,” “next,” and “finally,” you are using signposting embedded within the text in a basic way. In addition to this basic approach, you can also do higher level signposting, but let’s unpack the basic approach first before adding complexity.

Basic signposting with order-based terms tells your readers a few things, and you need to be aware that you’re telling your reader those things! Nothing is worse than when someone is signaling something while not realizing they’re signaling anything at all, or when they think they’re signaling something else entirely. If you’ve learned a foreign language, you’ve run into this issue with the subject of false cognates, terms that sound like words in your home language that mean something drastically different in the language you’re now speaking.

When you say something like “next’ to your reader, you are indicating that you’re working through a series of steps or ideas, and that you are now transitioning from one such idea/step to another. Being aware of this transition and taking advantage of it makes you a more effective technical writer and communicator. These terms are crucial in technical writing because many times the information we are conveying is quite complex. We don’t want to be adding to that complexity with even more complexity in our text. When we do so, we’re in effect creating two levels of understanding the reader needs to master: they need to master our text and our odd dialect/presentation and they need to master the actual information we’re presenting to them. For example, attempting to learn how to put together a set of furniture with instructions written in Middle English presents two challenges at the same time.

Now, I’m mentioning the two levels of understanding that readers have to deal with as separate entities to make a point, but in reality they are not so simple to break apart. Your “facts” can’t be separated from your presentation. “Just the facts” as an approach to technical writing, as we discussed previously, leads to a situation where you simply ignore the impact of your position as the author, of the format you choose for your facts, and even the impact of the medium you’ve chosen.

To use a metaphor, think about your signposting and textual decisions as one ingredient to a text or recipe. You also have outside information you’re including in the text as well, and these different ingredients react to each other while also having their own preparations that impact the way they are expressed. You can simply insert a table of data into a paper in the same way you add a stick of cold butter to a recipe. This impacts the way it works and how you will proceed and how your reader will proceed. You can also take the data from that table and instead of simply pasting the table, you can explain one bit at a time to the reader in paragraph form. This might be the equivalent of melting butter down and clarifying it before use. You have the same ingredient, but it’s being processed in different ways with different effects.

The signposts you add are like yet another ingredient, something perhaps like salt or yeast in a dough. To an extent, they are simply altering the way the recipe is going to be operate. More yeast, more rising. But, at the same time, they impart a flavor to the recipe. Yeast bread tastes fundamentally different than non-yeast bread. The same works with signposting in that terms like “next” impact the overall flow of the text and how someone reads it, but at the same time they add a distinct flavor to the text, signaling that this is going to be the sort of text where you get these types of aids, and that in the future you should look for them and depend on them.

Simple, order-based signposts are also an authorial aid—they help you think through your own series of steps and content. You need to know when you’re transitioning to use “next” effectively. You need to have an idea of steps to be able to assign points one, two, and three. In thinking about these, ideally you do so through the dual lenses of what you intend to say and who you intend to read your content, tailoring your choices based on those two elements at a minimum.

Advanced Signposting and Document Maps

To make the most out of simple signposting, you need to have a larger level of signpost that you can sync up with at the section level as well as at the document level. This is where signposting really shines!

Top-level signposting usually involves a section or document map of some sort. A document map functions just like the name suggests—it provides readers with a list of topics that will be covered or sections that will be present, and it usually does so while mirroring the order found in the text. You may have noticed a few maps in this document already, and if not, look for something with the following format:

In the next section, we’ll be looking at the shape of the material, the properties of the alloys that make up the material, and the relationship between these two elements and the friction forces the material creates.

In this example, you have a basic map that is connected to a larger map while also containing a section-specific map. First, you have the connection to a larger map with the terms, “In the next section.” This phrase lets us know that we’re moving from one major section to another, likely linking up to a larger list of sections that was introduced at the start of the text or the start of this series of sections. Next, you have the specific map for this section of text with the list of different aspects of the material that will be discussed. This list allows readers to know what will be coming up next, and as they transition through each of these steps, they’ll be able to mentally check their progress through the section based on this map. At the same time, they also realize this progression is the next in a larger series of progressions that make up the entirety of a given text.

Don’t underestimate the power of this approach! Document maps are essential for almost all technical writing that is more than a couple of paragraphs (and even then, I’d argue they are useful). Using a map, you provide the reader with a clear expectation of what content will be found and what order it will be found in. You can then use this in concert with basic signposting to move between sections/ points, or you can combine it with maps in each section listed to provide even more detail to the reader.

And, in larger documents that have a table of contents, all of this can sync up to that table and provide the reader a global view of the document map and the section maps.

Signposting Format or Why Headings Are Important

Having discussed basic and advanced signposting, I need to pause for a moment to discuss what this can look like in a visual sense. You could, and many people do, simply do all of this work in the text itself. You can locate the maps and the directional signposts in the text and when the reader encounters those maps, they can then use them accordingly. With that said, if you want your reader to get the most out of all your work creating maps of sections and sub-sections, you need to use headings.

Headings like the numerous headings you’ve encountered in this text already, are the key to making signposts really work for the reader. It is one thing to run into a map and to be able to then identify through the text when the next section has arrived. It is something entirely different to be able to see sections change by browsing through the text and noting the various textual landmarks the map has identified via bolded or italicized or colored headings and subheadings. These headings allow the reader to skim through your text to quickly locate a section they may want to read alone or reread.

In the context of usage, headings can help someone find content in a text that isn’t meant to be read as a narrative. Think about car manuals or recipe books. Neither of these texts really shines when you read them front-to-back. Yes, you can do that (and you might when you first get the text), but these texts are essentially a reference for someone who needs a slice of the data in the text. That’s also true in report settings where someone only wants the highlights of your text, or they want to see one particular part because of their role in an organization. We’ll discuss this more when we get to audience and use and again when we get to genre.

Taxonomy and Signposting

When we use the term taxonomy in technical writing, we’re referring to the way that we divide something in parts or sections. The study of taxonomy is really the study of how you divide something up and the impact of that division. You may wonder how that can be useful in a writing setting, or any setting at all, so let’s dive into how taxonomy can be used in specific scenarios.

How does taxonomy work?

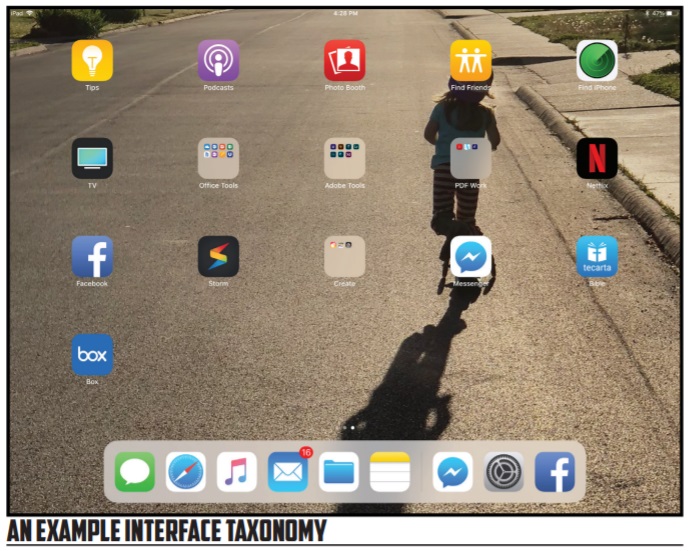

One simple example of taxonomy you may not be aware of is the way that you organize apps on the home screen of your phone. A taxonomy requires items and it requires groupings of those items as well as depth to those groupings, something the interface on your phone provides via pages of apps as well as folders. Take a look at the example of the iPad Pro interface I’m currently using as I write this chapter:

In the example above, I’ve got a rather terrible taxonomy that needs some work. I have three major groupings, some are useful and some are not. The overall order of the page seems to have no real sense to it. Why does Tips come first? What is the significance of Messenger next to Create? To be honest, there is no purpose here to those choices. I’ve simply left them in the order they were installed. All of these form the top level of the taxonomy’s hierarchy (we will ignore the shortcut bar for this example, though it does wonderfully compliment the discussion).

When I open up the iPad, these are my choices. I can navigate to the one I want via memory or via reading the various choices available. The advantage of the folders grouping things together is that I’m allowed to have more choices on the same page without muddling things up and at the same time I simplify the choices available. I can make the global choice, Office Tools, when I want to do something Office related. When I want to do something with Adobe, I can use that folder. This allows me to see those choices as a global choice alongside Tips and Messenger. It is a way of viewing and sorting the content on my iPad. As I said, it is not a very good way of doing this (I’ve not put a lot of thought and time into it), but it is a way of doing the content sorting.

Taxonomy really does come down to mundane things like my iPad Pro’s interface—how do we organize things and how do we label them and the groups we put them into? When it comes to phones and other devices, this impacts the way we use things and the way we find things. The principle also applies to physical workplaces with idiosyncratic stacking and filing methods. Taxonomy is nearly universal, but for the most part we’ll focus from this point onward on the impact it has on technical writing.

Taxonomy and Documents

When you create sections and sub-sections in a text, you are creating a taxonomy in/for your document. You are saying that this major heading describes the content contained within, and that certain sub-sections make sense in certain places. Not everyone will agree with every taxonomy you create, but that isn’t the point. The point is that you’re putting a sense of structure and hierarchy into place. This can be enormously powerful!

One thing to keep in mind about taxonomies, especially the top level of a taxonomy, is what the taxonomy you’ve created makes visible and what it hides. Top-level choices are given a great deal of importance and they may be the only level someone ever really reads or considers before diving into your text or passing on it altogether. You need to calculate what you say very carefully to make sure folks know what to find where and what to expect.

If you’ve ever tried to evaluate four or give different programs at the college level using the respective programs’ websites, you know the pain of awful taxonomy choices. One school might choose to put the major plan under “Advising,” while another will put it under “New Students,” and another will place it under “Academics.” Where you will find it on a given website is anyone’s guess since the taxonomy is not regularized (this is one of the reasons the standards we discussed previously can be useful—a taxonomy can be universal) or is simply poorly thought out. In many cases with websites you can get to the information quicker by doing a web search with the terms and the university name than actually diving into the site. This isn’t an ideal solution, but it is often one bad taxonomy forces on us. (Card Sorting research is one way to fix this, so take a peak at that section in our last chapter for more).

You may wonder how taxonomy and power interrelate. We are after all just naming categories—why would we care about the top level? Well, it comes down to representation and access. Taxonomies have an implicit power structure. Top level content is all of equal importance. Secondary content is less important than top level content, and in theory it is all of equal importance. If there is a tertiary level, it in theory is less important than the secondary level and all content at that level is ideally of the same importance. This is basically how an outline works with Roman numerals:

I. Topic 1

a. Sub-Topic 1

i. Sub-Sub-Topic 1

b. Sub-Topic 2

II. Topic 3

III.Topic

Because of the weight given to the top level, and it’s immediately visibility, it provides a level of prestige that the sub-levels don’t have. Think about how this can impact something as simple as an organizational chart. Does a unit deserve to stand alone as part of its own subdivision of the organization, or does it get nested under another unit? These are functional as well as political questions. (Office politics gets really interesting around these issues).

Ethics and Taxonomy/Signposting

For us, we want to make sure that we’re using a taxonomy system that both respects the subject matter and makes content easy to find. Doing both isn’t always easy, but if effective communication was something that was relatively easy, everyone would be doing it! Writing and communication classes exist for a reason.

You want to group categories in a way that makes sense to your readers, even if it isn’t your natural way to categorize. This sometimes involves research, and we’ll cover that later in the text, but it is almost always worth the work. Connect research on how readers classify content with your signposts in the text, sync those road maps up with your document map, and the next thing you know you’ve got a text that will serve readers well.

Regarding respecting content, you want to make sure that you’re treating content with the same level of respect as your readers, and that you’re respecting the importance of content when viewing it through an ethical lens. Practically speaking, this often means making sure that you aren’t tucking important information that might make your case less persuasive in hard-to-find places. You shouldn’t have safety warnings or hidden price tags for projects in places folks are not likely to look or very likely to overlook. Doing so betrays your audience by actively preventing them from accesses the information they would want to see when they are making decisions about your text.

Wrapping it Up

In short, this chapter has been about the big picture of technical writing. What is it? Why does it matter? What are some of the simple-yet-important things we need to keep in mind when writing texts on technical subject matter? From this point on, we’ll be expanding our knowledge in particular areas regarding technical writing. But, we’ll rely on this chapter and the content covered to move forward.

Section Break - Taxonomy and Signposting

- How does taxonomy work in your major? Are there different expressions of the major, or does the major rely on minors for flavor?

- What taxonomies break up your student body? What are the universal taxonomies, and what taxonomies emerge that are tied to your institution?

- Study the taxonomy of your major’s website. Does it agree with other majors in the institution? Does it agree with other majors at other institutions? Using the Card Sorting research method in the last chapter, take the major sections and sub-sections of the website and test it with folks in the class. How does their ordering of the content differ from your major’s website? Which do you prefer? Why?