4.3: Voice

- Page ID

- 15244

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

Be true to your strengths. The more authentic you are in your writing, the more likely your readers will be to listen to what you have to say. [Image: Jason Rosewell | Unsplash ]

Definition to Remember:

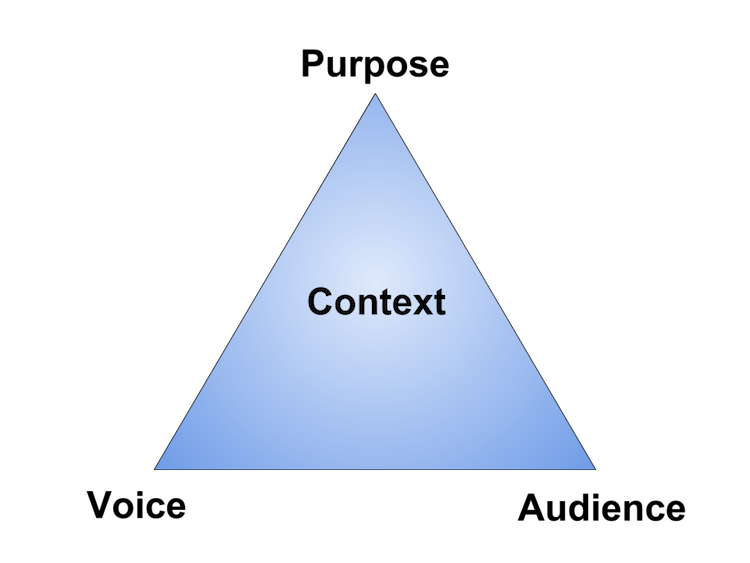

A 21st Century Rhetorical Triangle

Rules to Remember:

- Who you are is just as critical as your purpose and your audience. Without a keen understanding of your own background, assumptions, and biases, you may say or express your ideas in a way that have an effect on your audience that you never intended. If, for example, you are a retired African-American man in your 70s who had an affluent career and home in the Pacific Northwest, you must be mindful of who you are when you speak to a group of young single white mothers in southern Louisiana or a community of Chinese-American high school students in northern California. Your voice can have a profound effect on how your audience hears the ideas you hope to convey.

- Be honest with yourself. Are you able to define yourself with the same specific terms that you defined your audience? Consider the following:

- How old are you?

- What is your gender?

- What is your race and/or cultural background?

- Where are you located, and where are you from?

- What is your education level and economic status?

- What primary religious beliefs do you hold?

- What do you value? What are your interests?

- Are you part of a specific group of people? What groups do you associate with, and how would other people classify you?

- What biases do you hold? What misconceptions might you have about a particular topic or group of people, particularly considering your answers to the questions above?

- What language or jargon do you use that others might not immediately understand? What terms will you need to define as you speak to others? What background information will you need to provide?

- Be honest with your readers. Your audience will nearly always be in a hurry, looking for holes to poke in your argument and your character. If you exaggerate or inflate yourself in any way, your audience will likely set your ideas aside as inconsequential or silly. Instead be forthright and honest with your audience, seeking answers alongside them rather than setting out to prove your superiority. As always, only write the words that you would want to read, and most of us don’t like to be talked down to, particularly if we suspect that someone is not being entirely honest with us.

- Choose your words, examples, and approach mindfully. Your voice is uniquely yours and the best part of what you have to offer in this information-drenched world. The better you understand the elements that define who you are, the better you will be able to use your voice with intentionality. Consider the following as you seek to define your own voice. Are the choices you make intentional or be default? Are the habits you have effective in speaking to the audiences you intend to reach, or should you learn to be more nimble with the elements that comprise your narrative voice?

- word choice

- sentence length

- paragraph length

- point of view

- punctuation choices

- emotional appeals

- appeals to logic

- storytelling

- use of bullets, direct quotes, charts, or illustrations

- humor

- direct vs. indirect address

- opposing arguments

- conflict

- authority

- diction, syntax, and tone

- Be true to your strengths. Not everyone can master every element of effective rhetoric – nor should we. Instead learn to articulate who you are and how you come across to others, and play up the areas where you feel most comfortable and inspired. For example, if humor comes naturally to you, find ways to incorporate it in your writing. If you appreciate a sad story, consider how to use emotional appeals and storytelling in your writing. The more authentic you are in your writing, the more likely your readers will be to listen to what you have to say.

“The tormented artist shtick is passé – I am into authentic. Write from who you are, where you are, and where you’ve actually been.” Paul Ruddock, Doctor of Ministry Student

Common Errors:

- Assuming that voice comes naturally and therefore cannot be altered. While your spoken voice is inherently you, how you express that voice in writing is dependent on a number of choices that can and should be made with intentionality.

- Not realizing that voice is as important as purpose and audience. We typically learn about purpose in elementary school, and – if we’re lucky – we begin to consider audience in high school. A discussion of voice sometimes happens in late high school or college, but many writers never hear it at all, which is a shame. If purpose, audience, and voice are all equally important, how can you ensure that your approach to writing honors them all evenly and consistently?

- Not recognizing the ways that voice can inspire or shut down an audience. We have all watched the eyes of someone we are speaking to slowly glaze over with boredom, anger, or irritation, even when we are begging them to keep listening, but once that wall goes up, it can be difficult to get the other person listening well again. What can you do in your writing to ensure that the wall stays down and communication remains effective?

Exercises:

Exercise 16.1

Answer the following questions as thoughtfully and thoroughly as possible.

- How old are you?

- What is your gender?

- What is your race and/or cultural background?

- Where are you located, and where are you from?

- What is your education level and economic status?

- What primary religious beliefs do you hold?

- What do you value? What are your interests?

- Are you part of a specific group of people? What groups do you associate with, and how would other people classify you?

- What biases do you hold? What misconceptions might you have about a particular topic or group of people, particularly considering your answers to the questions above?

- What language or jargon do you use that others might not immediately understand? What terms will you need to define as you speak to others? What background information will you need to provide?

Exercise 16.2

Consider the following elements as you seek to define your own voice. How do you fare, and what would you like to improve or change?

- word choice

- sentence length

- paragraph length

- point of view

- punctuation choices

- emotional appeals

- appeals to logic

- storytelling

- use of bullets, direct quotes, charts, or illustrations

- humor

- direct vs. indirect address

- opposing arguments

- conflict

- authority

- diction, syntax, and tone

Exercise 16.3

Consider a writing assignment you have completed recently, whether for work, school, or personal use. What was you purpose, and who was your audience? How would you describe your voice, using the language in the chapter above? Was your voice effective in achieving what you hoped to accomplish? Why or why not? If not, what revisions would you make?