1.4: Types of Features

- Page ID

- 126049

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)“If my doctor told me I had only six minutes to live, I wouldn’t brood. I’d type a little faster.”

Isaac Asimov

Truth be told, no one writes a plain, old feature article, since “feature” is an umbrella term that encompasses a broad range of article types, from profiles to how-tos and beyond.

The goal here is not just to know these types exist but rather to use them to shape your material into a format that best serves your reader and the publication for which you are writing. Pitching a story that takes a particular format or angle also helps editors see the focus and appeal of your idea more clearly, which can help you get hired.

Let’s take a look at some of the most common feature article types.

Profiles

A profile is a mini-biography on a single entity — person, place, event, thing — but it revolves around a nut graph that includes something newsworthy happening now. That “hook,” as we call the news focus, must be evident throughout the story.

A profile on Jennifer Lawrence might be interesting, but it is most likely to be published about the time she has a new movie coming out or she wins an award.

This fulfills the readers’ desire to know why they are reading about someone at a given time or in a given magazine.

The best profiles examine characters and document struggles and dreams. It’s important that you show a complete picture of who or what is being profiled — warts and all — especially since the controversy is often what keeps people reading. Controversy, however, is not the only compelling aspect of profiles. They are, most importantly, personal and insightful, beyond the pedantic list of accomplishments you can get from a bio sheet or a PR campaign.

Profiles aim to:

- Reveal feelings

- Expose attitudes

- Capture habits and mannerisms.

- Entertain and inform.

Accomplishing those goals is what makes profiles challenging to write, but also makes them among the most compelling and fulfilling stories to create.

Delving deeply into your subject’s interests, career, education and family can bring out amazing anecdotes, as can reporting in an immersive style.

The goal is to watch your subject closely and document his or her habits, mannerisms, vocal tones, dress, interactions and word choice. Describing these elements for readers can contribute to a fuller and more accurate presentation of the interview subject.

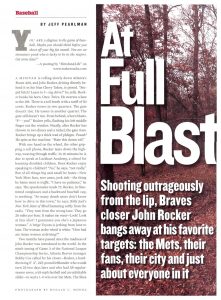

Consider this opening paragraph from one of my favorite profiles, Jeff Perlman’s look at one-time baseball bad boy John Rocker of the Atlanta Braves:

A MINIVAN is rolling slowly down Atlanta’s Route 400, and John Rocker, driving directly behind it in his blue Chevy Tahoe, is pissed. “Stupid bitch! Learn to f—ing drive!” he yells. Rocker honks his horn. Once. Twice. He swerves a lane to the left. There is a toll booth with a tariff of 50 cents. Rocker tosses in two quarters. The gate doesn’t rise. He tosses in another quarter. The gate still doesn’t rise. From behind, a horn blasts. “F— you!” Rocker yells, flashing his left middle finger out the window. Finally, after Rocker has thrown in two dimes and a nickel, the gate rises. Rocker brings up a thick wad of phlegm. Puuuh! He spits at the machine. “Hate this damn toll.”

Perlman does not have to tell us anything about Rocker; he has shown us and lets us make our own determinations as to the person we are getting to know through this article.

Research is key to any piece, but profiles provide the ultimate test of your interviewing skills. How well can you coax complete strangers into sharing details of their private lives? Your job is to get subjects to open up and share their true personalities, memories, experiences, opinions, feelings and reflections.

This comes from a true conversational style and a willingness to probe as deep as you need to get the material you need.

Interview your subject and as many people as you need to get clear perspectives of your profile subject.

Not everyone will make your article, but you can get background information and anecdotes that could be crucial to understanding your subject or asking key questions. (Now might be a good time to download “Always Get the Name of the Dog.”)

Take the time to watch your subject at work or play so you can really get to know them in a three-dimensional way.

The fewer sources and the less time you spend with your subject the less accurate or complex your profile will be.

The framework of a profile follows these guidelines:

Anecdotal lede

An engaging, revealing a little story to lure us into your article.

Nut graph/Theme

A paragraph that shows the reader what exactly this story is about and why does this entity matter now?

Scene 1

Observe our subject in action now using dialogue details and descriptions.

Chronology

A recap of our subject’s past activities using facts, quotes and anecdotes as they relate to the theme.

Where Are We Now?

What is our subject doing now, as it relates to the theme?

What Lies Ahead?

Plans, dreams, goals and barriers to overcome.

Closing Quote

Bring the article home in a way that makes the reader feel the story is complete like they can sigh at the end of a good tale.

Q&A

A Q&A article is just what it sounds like — an article structured in questions and answers.

Freelancers and editors both like them for several reasons:

- They’re easy to write.

- They’re easy to read.

- They can be used on a variety of subjects.

The catch is writers/interviewers must take even greater care with the questions asked and ensuring the quality of the answers received because they will provide both the skeleton and the meat of your piece.

This may seem obvious, but quality questions are vital, meaning we avoid closed-ended (yes or no, single-word answer) questions and instead ask questions that will inspire some thought, creativity and explanation or description.

Q&A articles start with an introduction into the subject — often as anecdotal as any other piece, but then transition into the fly-on-the-wall feeling of watching an interview take place. You are the interviewer.

The subject is the interviewee, and the reader is sitting alongside you both soaking in the experience and your relationship.

That means a Q&A has to stay conversational so it does not feel like a written interrogation.

The interview itself is much like we would use for an article, but you have to be more conscious of the order in which you ask questions, how they transition from one another and the quality of the answer so you are not tempted to move answers around.

You will be amazed at how many words get generated in an actual conversation or interview, so the Q&A is far from over when the interview concludes. Editing and cutting the interview transcript can take far longer than the interview itself.

You cannot change your subject’s words, but you take out redundancies and those verbal lubricants that keep conversations moving — “like,” “you know,” etc., Sentences and phrases can be edited out by using ellipses (…) to show you have removed something.

Grammar is a challenge with a lot of transcripts, and I will leave in that which represents the subject, but I will not let them come across badly by misusing words or phrases.

Instead, let’s take it out or ask them to clarify.

Round-up

If you do an internet search on “round-up story,” you very often get a collection of information from various places on a central them.

Feature round-ups are written the same way.

These articles are like list blog posts, where you have a variety of suggestions from different sources that advance a common idea:

- 7 secrets to a happy baby

- 10 best vacation spots with a teenager

- 5 tips on how to pick the perfect roommate

You may notice that there is a numeric value on each of these ideas, and that is a key part of the roundup. You are offering a collection of suggestions, provided and supported by sources, on a specific topic.

The article begins, as most features do, with an anecdote that takes us to a theme, but instead of a uniform or chronological body style, we break it up into these sections outlined by each numbered suggestion.

Each section can be constructed like its own mini feature — complete with sources, facts, anecdote and quotes, or just the advice provided by a qualified source (not the author!).

There does not need to be a specific order to how each piece of the article is presented, rather their order is interchangeable.

It is important to have sources with some level of expertise and not merely opinions on the topic. Just because someone went to Club Med with their 5-year-old and had fun does not mean it’s the best vacation spot for kids.

We first need an idea of what makes a good vacation spot and then support with facts how this one fits the criteria.

How-To

Readers love to learn how to do new things, and there are few better ways to teach them than through how-to articles.

How-to articles provide a description of how something can be accomplished using information and advice, giving step-by-step directions, supplies and suggestions for success.

Unlike round-ups, these articles must be written sequentially and have to end with some sort of success.

Aim for something that most people don’t know how to do, or something that offers a new way of approaching a familiar task. Most importantly, make sure it is neither too simplistic, nor too complex for their attempt, and include provide definitions and anecdotes that show how things can go well or poorly in attempting this task.

Personal Experience

Most of us have had some experience that we think, “I would love to write about this so other people can learn or enjoy this with me.”

If you have a truly original and teachable moment and can find the right feature to which to pitch it, you may very well have a personal experience story on your hands.

Some guidelines for finding such a story include whether this is an experience readers would:

- Wish to share?

- Learn or benefit from?

- Wish to avoid?

- Help cope with a challenge?

Unlike a first-person lede, which might use your personal anecdote to get us into a broader story, in a personal experience article you are the story, and how we learn from your experience will help us navigate the same waters.

They can be emotional, like the New Yorker piece on women who share their abortion stories, but they can also be about amazing vacations that others might consider — “Bar Mitzvah trip to Israel” anyone? — or how about a man who quits a high-powered job to stay home with his kids?

No matter what your experience, you must be willing to tell your story with passion and objectivity, sharing the good, the bad and the uncomfortable, and making readers part of the experience.

It’s important that the experience is over before you pitch, so the reader can get a clear perspective of what happened and the resolution. Did it work or not?

As the author, you also need time to gain perspective on your issue so you can “report” it as objectively as possible.

Finally, make sure you are chronicling something attainable or achievable. We need to go through it and come out the other side with evidence that will make us smarter and better equipped to handle a similar situation that might come our way.

The Art of Covering Horse Racing

Melissa Hoppert is the racing writer from the New York Times, and despite covering the same events over and over she manages to find a unique story each time.

Belmont Park is called “Big Sandy,” because the track has so much sand on it. I rode the tractor and asked the trackman, “What makes it like that? What it’s like to race on it?”

It was my most-read story that year. You have to think outside the box.

When the horse Justify came along, it was like ”here we go again — another Triple Crown with the same trainer. What can I possibly write about Bob Baffert that has not written before?

We observed and thought outside the box. We didn’t do a Bob Baffert feature. We went to the barn and still talked to him every day, but we looked at things differently.

We focused more on the owners. They were in a partnership and that is a trend of the sport. Rich owners team up to share the risk. That made it more of a trend story. Is this where we are going.

Sometimes I like writing about the horse. American Pharoah was a really fun, quirky horse. My most favorite story was when I went to visit American Pharoah’s sire, Pioneer of the Nile, at the breeding shed. He has a weird breeding style. He needed the mood to be set. It was kind of random, but it helped tell a story of American Pharoah that had not yet been told.

True-Life Drama

Examples of these include:

- The couple on a sight-seeing plane ride that had to land the plane when their pilot died

- Aron Ralston frees himself by sawing off his own arm after getting trapped in the desert.

- Tornado survival stories

It is fitting that the first example I found to show you of true-life dramas came from Readers Digest because these types of stories are the bread and butter of that magazine.

They are the stories that are almost impossible to believe but are true, and they are driven by the characters who make them come to life.

Some “true-life dramas” become even more famous when they are adapted for the screen, like the Slate story of being rescued from Iran, you might know better as the film, “Argo.”

How about Capt. Richard Phillips’ dramatic struggle with Somali pirates, now a film starring Tom Hanks?

Steve Lopes of the Los Angeles Times found a violin-playing homeless man who became the subject of numerous columns and later the movie “The Soloist.”

These stories are, quite simply, dramatic experiences from real people, where they live through moments few of us can imagine.

Many of the feature versions of these stories start as newspaper coverage of the breaking event, and then a desire to go behind-the-scenes and chronicle exactly what happened over a much longer course of time — the lead-up, the culmination and the aftermath.

Being a consumer of news will help you come across these stories, and a desire to conduct really penetrating interviews to get the “real story” will make them come to life.

Seasonal

You might not be thinking about Christmas in May or back-to-school in February, but chances are editors will be scheduling those topics and looking for article ideas.

Seasonal stories are the ones that happen every year and need a fresh angle on an annual basis.

It goes beyond standbys like “Best side dishes for Thanksgiving,” and how to make a good Easter basket, to “How to do the holidays in a newly divorced family,” and “Back to school shopping for a home-schooled child.”

The key is that a timely observance is interwoven in the theme, and these stories are planned and often executed months in advance since we all know they are coming.

Seasonal can also relate to anniversaries — Sept. 11, Martin Luther King Jr. Day, Titanic sinking — and their marketability can escalate dramatically around an anniversary.

The angle is all about the audience, so think how you can spin one day or a milestone event to toddlers, teens, seniors, your local community, pets, business, food, travel and you may suddenly have 10 stories from one topic.

Remember, though, that your pitch has to come long before the event is even in the mind of most readers — at least six months and sometimes a year.

Travel

The perceived glamour division of freelance writing is the travel piece, which most people think comes with an all-expense-paid trip to swanky, exotic locations.

That can be true, but more likely writers make their own plans and accommodations and their pay reflects that a portion of their compensation comes from the good time they had traveling.

The good news is that with the rise of travel blogs and smaller travel publications there are more outlets than ever to pitch your ideas, provided they are original and unique to the audience.

That means, “Traveling to Paris,” probably won’t work, but “Traveling to Paris on $50 a day” just might.

That also does not mean that publications are looking for your personal essay on what you did for your summer vacation, or just because you visited Peru and loved it that it’s worthy of a feature article. You have to show the editor and the reader why you have a unique perspective and angle on a traveling experience.

Travel writing means looking for stories on about:

- How to travel

- When to travel

- Advice on traveling

The more specifically you can focus on a population of travelers — seniors, parents, honeymooners, first-time family vacation — the more likely you can come up with an idea that has not been overdone and pitch it to a niche magazine.

In a column on the Writer’s Digest website, Brian Klems writes the need to travel “deeply” as opposed to just widely, and I thought that was such an insightful term. He spelled out the need to really dig deep into whatever area you might cover and take copious, detailed notes, but I would add that you also have to really dig deep into what people want to know about travel and enough to go past the cliché or stereotypes.

The more descriptively you can present experiences, the more compelled readers may be to join you.

To separate yourself from the cacophony of travel voices out there, consider building up expertise in one subject or area. If you are from an interesting area, see how you can pitch stories to bring make outsiders insiders. Are you a big hockey fan? What about traveling to different hockey venues and making a weekend travel story out of what to see and do before and after the game?

The key to success is to become a curious and perceptive traveler from the minute you book a trip. Think about how your experience can be a travel story, as opposed to only looking to pitch stories that could become an experience.

Some other types to consider:

First-person pieces, which usually revolve around an important or timely subject (if they’re to be published in a newspaper or “serious” magazine).

Focus on a single historical aspect of the subject but make a current connection.

Takes the pulse of a population right now, often in technology, fashion, arts and health.

No, we are not talking about trees.

Evergreen stories are ones that do not have an expiration date and can be pitched for creation at any time.

A profile on a new trend or profile-worthy person has to be pitched in relatively short order, or it will not really marketable anymore. But a story on how to build an exercise program around your pet does not really have to be published at a specific time.

Incorporating evergreen ideas into your repertoire of story ideas will open up even more publishing doors.