1.10: CREAC Legal Writing Paradigm

- Page ID

- 143678

Effective organization of your legal analysis allows the reader to clearly understand your analysis or argument, which makes the reader better able to side with your reasoning. Effective organization also enhances your credibility. Legal writing typically follows a particular organizational paradigm that legal readers expect to find. You should use an appropriate organizational structure when writing the body paragraphs of your analysis or argument. Organizational paradigms serve to strengthen writing through providing clarity rather than weaken writing through rigidity.

So, what is this magic paradigm that everyone is supposed to use? Well, there is no single format that everyone agrees on. There are similarities across all formats, and keeping those similarities in mind will lead to effective organization of your analysis. Good organization in legal writing “include[s] rule-centered analysis, separation of discrete issues, synthesis of the law, and unity.” Tracy Turner, Finding Consensus in Legal Writing Discourse Regarding Organizational Structure: A Review and Analysis of the Use of IRAC and Its Progenies, 9 Legal Comm. & Rhetoric: JALWD 351, 352 (2012).

Keep in mind that these organizational structures are intended for use with your legal analysis paragraphs only. Introductory sections, statements of fact, questions presented, brief answers, and conclusion sections all have their own separate preferred organizational structure that we will discuss as we practice those units.

CREAC Structure and Overview

In this course, we will be using CREAC as our legal writing organizational paradigm. At its most basic, this acronym stands for:

C - Conclusion

R - Rule

E - Explanation

A - Application

C - Conclusion

However, that description is not particularly helpful for novice writers, so I have expanded on the letters to provide the following details.

C - Conclusion, overall, to the particular issue that is to be addressed; topic sentence about what the remainder of the section will discuss and that the rest of the block will prove.

R - Rule to be applied to reach the conclusion stated at the beginning of the section; use the specific issue within the rule that will be addressed in this block.

E - Explanation of how the rule has been applied in past cases using those past cases’ facts, reasonings, and holdings; this is the education piece of your analysis where you teach what your reader needs to know about the rule’s use in the past so the application to the current case will make sense. This about this as your education section.

A - Application of the rule to the current situation you are addressing; you will fact-match using analogy and distinction, and this is where you will be explicitly proving the conclusion that you stated at the beginning. Your counteranalysis, where you predict the other side’s argument and then refute, also goes here. Think about this as your action section.

C - Conclusion, detailed, to the particular issue that was addressed in the block; summarizes the R/E/A without introducing any new ideas and reinforces what you want the reader to take away from this block.

When to use CREAC

You will use CREAC any time you are conducting an analysis or presenting an argument of a particular legal question as applied to a specified set of facts, such as in a legal memorandum or a brief. If you do not have facts to which to apply the law, such as in a Summary of Law, then you will use a modified legal writing paradigm of CRE-C, where you will not have an A section because there is no “application” of the law to any facts.

Before you start writing any legal analysis, be sure that you understand the law you need to explain and apply. Go back to your rule and case synthesis materials and confirm you are confident in your comprehension. If you are uncertain or unclear in

your own mind, then that will be conveyed through your muddled writing to your reader. You want your writing to be as clear, concise, and crisp as possible!

Once you begin writing the legal analysis portion of the legal document, break down your rule statement for each issue into its parts. Then, use one CREAC-block per each part of the rule statement. The part could be defined by issue, by portion of the issue, or by the entire rule, depending on what the whole legal analysis calls for. Refer to Rule Synthesis and Case Synthesis chapters for more information.

CREAC Structure Explained In-Depth

The first C of CREAC serves as your topic sentence for the particular legal issue you are addressing. This is where you offer your general conclusion to the legal question posed; remember that you will give more details in your second C at the end of your CREAC-block.

The R of CREAC is the synthesized legal rule that should be applied to a specific situation. The rule is the skeleton, devoid of meaty facts, that provides what courts should consider as they flesh out the answer to the current legal question with the specific facts before them. The rules that we typically seek in this class are the core substantive rules about how to answer the substantive legal question; be aware there are also supporting rules that address how a rule should be applied or what the timing is for when a particular rule should be applied. The Rule Synthesis chapter goes into a lot more detail.

Organize your Explanation by the issue, key fact, or similarity that you identified in your case synthesis process. Do not write a series of case summaries. Your goal as a writer is to do as much of the work as possible for the reader. When you organize by case rather than by issue, you are shifting analytical work to the reader to decide what you mean. In this section, you are not referencing the facts of your case yet. In your Explanation, you are setting up for your reader all the facts and reasoning from past cases that you will later use in your Application section. Think of yourself as laying out all the cooking ingredients that you will need to bake a cake before you begin to mix any ingredients together.

Be sure that your Explanation includes cases on both ends of whatever spectrum is created by your legal question. For example, you will want to examine cases that find a battery did occur and cases that find a battery did not occur. Even more specifically, you will want to examine cases that differ on what the outcome was for each element or factor of the legal question you are addressing. To continue with the battery example, you would want to consider cases where there was an intentional touching and where there was not an intentional touching.

Every case that you will use in your Application section, whether it be to prove your analysis-in-chief or to demonstrate a counteranalysis, must be included in your Explanation section.

Your Application component should start with analogizing and distinguishing the past sources of law that you have laid out in your Explanation section with the facts of the current situation. The rest of the Application should prove that your analogy is correct. Weave your analysis using facts, reasonings, and holdings together.

Fact-Matching

For conducting this weaving-together, I recommend you use a technique I call fact-matching. By using fact-matching, you ensure that you show how each piece of the rule that you have identified was used in past cases and thus how it should be considered in your current situation. Fact-matching allows you to connect the facts from the past cases to the facts in the current situation so that the work you did explaining how the rule played out in the past cases can quickly link up to your application to the current situation.

Fact-matching does not always mean you have to create comparisons where the fact from the past case and the fact in the current situation are similar. In fact, you should be both analogizing (showing how they are the same) and distinguishing (showing how they are different) facts from the past cases and facts in the current situation. You will use phrases like, “Like the plaintiff in X, the client here…” or “Unlike the child in Y, the child here…”

Think of fact-matching as getting to finally put the pieces of the puzzle together that you have been carefully laying out, sorted into edge pieces and middle pieces and certain portions of the overall picture. You are finally getting to assemble the scene that you have found through your research and analysis, and you are showing the reader how to replicate your results.

Counteranalysis

Remember that you will place your counteranalysis in the Application section, but that you will get to the counteranalysis only after you have completed your analysis-in-chief. The purpose of a counteranalysis is to show the reader why the outcome you are predicting for the current situation is more likely than the opposite outcome. For example, when presenting Plaintiff’s claim of battery against Defendant, there will be a counteranalysis component that identifies the strongest argument against Plaintiff’s being successful in a battery claim against Defendant, but you will then show why that argument will fail. In other words, you are setting up the other side’s strongest argument only to knock it down quickly.

Then, for your conclusion statement, summarize for the reader what you have shown in your CREAC-block. Continue this pattern until you have analyzed each part of the rule and each issue.

Examples

How your R sets up will determine how you set up your E and A sections. Rather than trying to explain this in general terms, it is easier to understand with an example. To return to the battery hypothetical, when you sit down to write the R for battery in your introductory paragraph, your rule should look something like this:

The requirements to prove battery in Georgia are (1) a touching; (2) that is intentional; (3) in an offensive manner; (4) with either the intent to cause harm or to cause insult or offense, or both.

When you go to write a CREAC-block to examine each piece of the rule, you will use a CREAC-block for each part of the rule that is at issue, meaning that the parties do not agree on both the facts and their legal significance. Assuming that nothing is a given, you will need four CREAC-blocks.

(1) a touching;

(2) that is intentional;

(3) in an offensive manner;

(4) with either the intent to cause harm or to cause insult or offense, or both.

For the first part of the rule, (a touching) your CREAC-block would set up as follows:

C - Yes, a touching occurred.

R - The rule to determine whether the touching occurred

E - How the rule has played out in past cases to show whether a touching occurred

A - How the rule will likely play out in the current situation

C - Yes, the touching occurred because...

The second and third parts of the rule would set up similarly.

For the fourth part of the rule (either intent to cause harm or to cause insult or offense), however, the CREAC-block will set up differently.

C - Yes, there was intent to cause harm and to cause insult or offense.

R - The rule to determine whether there was intent to cause harm.

R - The rule to determine whether there was intent to cause insult or offense.

E - How the rule has played out in past cases to show whether there was intent to cause harm.

E - How the rule has played out in past cases to show intent to cause insult or offense.

A - How the rule will likely play out in the current situation about intent to cause harm.

A- How the rule will likely play out in the current situation about intent to cause insult or offense.

C - Yes, there was intent to cause harm and to cause insult or offense because...

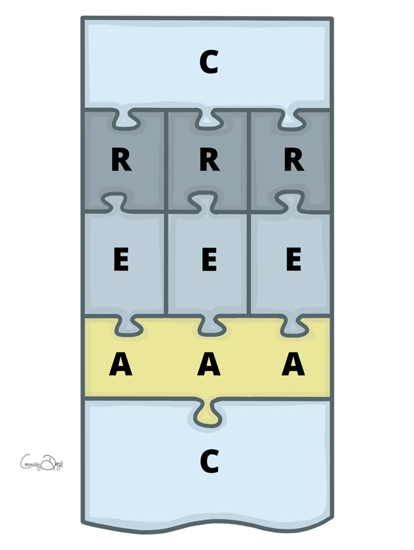

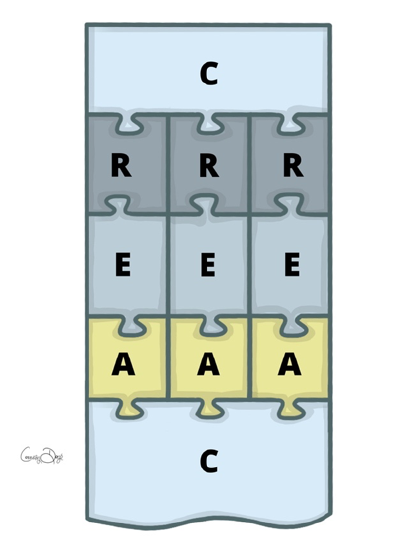

The two graphics below show the two different ways that CREAC-blocks can break down based on what the rule calls for to supplement the written description above.

Setting Up Your CREAC-blocks

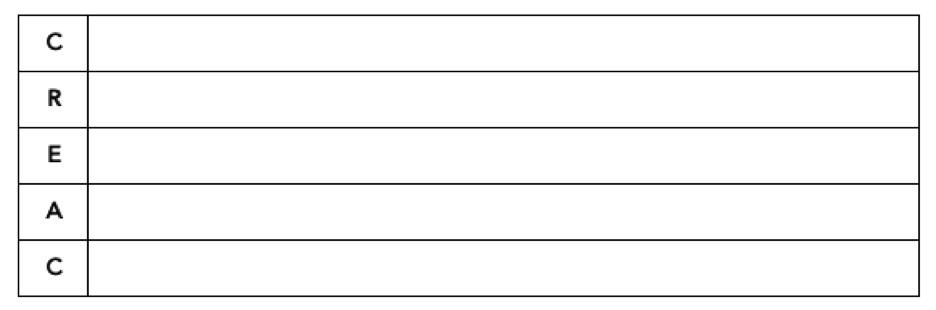

One way to set up your CREAC-blocks when you are brainstorming or outlining would be to use a table like the one below, so you can be sure you are addressing each component.

Once you begin writing more complicated legal analyses, you might have to stray from this setup. That is absolutely fine. At the beginning of your legal writing career, however, stick with this organizational schema to make sure you include all relevant portions of your analysis so that your work is thorough and complete.

Conclusion

Using CREAC for the analysis portions of your legal writing will ensure that you thoroughly demonstrate to the reader each piece of your analytical process so that the reader can use your writing as an effective tool.

For Further Reading

David Romantz & Kathleen Elliot Vinson, Legal Analysis: The Fundamental Skill 89-105 (1st ed. 1998).

Jill Barton & Rachel H. Smith, The Handbook for the New Legal Writer 27-30 (2014).

Tracy Turner, Flexible IRAC: A Best Practices Guide 20 Legal Writing: J. Legal Writing Inst. 233 (2015).

Tracy Turner, Finding Consensus in Legal Writing Discourse Regarding Organizational Structure: A Review and Analysis of the Use of IRAC and Its Progenies, 9 Legal Comm. & Rhetoric: JALWD 351 (2012).