3.1: Reading Exercise - Bound

- Page ID

- 275908

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)

Image by Antonio_Cansino from Pixabay

Bound

By James Thibeault

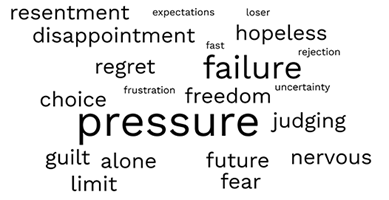

If a word cloud popped over my head as I stood outside of the family restaurant, it would probably look like this:

I probably do about 40 paces in front of the door, and thankfully the only person who sees me is Stu, one of our restaurant servers. Eventually, he gingerly opens the entrance door and knocks—as though he is entering my bedroom unannounced.

“Everything okay, Samira?”

“Yeah, oh, totally, just getting some steps in. You know these watches, if you don’t hit a certain amount, they just start beeping and beeping and soon it stresses you out. Then you get mad at it, but then you shouldn’t get mad at it because it’s a watch. The watch did nothing wrong! It’s not demanding that you give up your whole future because of some tradition. It just wants you to be healthy and your best self. Is that such a bad thing, Stu?”

“Uh, sure. Best to listen to Mr. Watch. Completely unrelated, do you press F5 when the screen blinks or F6?”

I feel throbbing pulsation under my eyes. My fists clench and I bite my teeth. Despite everything else, now I have to deal with this?

“You pressed F6 again, didn’t you?”

“So, that’s the bad key?”

“Yes! F5 refreshes the graphical interface. F6 is a hotkey for printing, but since our printing server broke it completely stalls the entire program. We went over this, multiple times!”

“Right … so you can fix it.”

I look up at the sky and groan. If I still smoked cigarettes, I would take the largest drag I could and flick the butt into the street—scoring bonus points if I managed to get it into the gutter. But I finally quit because my father, my mother, my brother, and the dog (technically by secondhand) all smoke. Every ounce of my body wanted a drag at this moment, but I wouldn’t give in. I had to change. Everything had to change.

“Give me a minute, Stu. Just don’t touch the computer, and write down the names of anyone reserving a table until then.”

“Gotcha, you’re the best, Sammy.”

Breathing helps. I breathe in for four seconds, hold, and breathe out for four. Considering my lungs are that of an old man, I struggle for the first few rounds. Eventually, a cold sensation fills me. It cools down the flaming frustration that has been building inside of me. It doesn’t extinguish the flame—only reducing it to a flicker. Still, the heat is manageable now. I can at least fix the system before I have to talk to my parents.

I open the front door and wander through the smokey haze. This town is notorious for ignoring smoke-free areas. Technically, our restaurant only allows smoking on the second floor, but we have never been written up by the fire marshal or the health inspector, so anyone smokes anywhere. It’s one of those things where you don’t notice how bad it is until you stop doing it. After a few coughs, I make my way to the glowing monitor that Stu is hovering around.

“Can you stand somewhere where you’re not in throwing distance?” I ask.

“Sure thing, boss,” Stu says obediently. He immediately goes to the bar and starts wiping away the crumbs on the counter.

“Wait, let me show you how to fix it.”

Surprised, Stu comes back but not exactly within throwing distance.

“You want to show me?”

“Yeah, it’s not that difficult.”

“But your dad says any computer thingies need to go be run—”

“I don’t care what ab says. You need to be independent, fix your own messes.”

“Alright,” says Stu. I guide him over to the screen and explain what the error message means. I don’t bother explaining the technical issues regarding our antiquated printer servers because he just needs to learn how to do a reboot in case it freezes up. I deliberately crash the computer again, so he can fix it. After a moment, Stu presses the right keys.

“Tuhani, well done!”

“Wow, that’s all I have to do?”

“Yup.”

“So, I don’t have to stress you out as much now?”

“Let’s not get too excited.” I smile and pat him on the back.

A large family enters through the front, so I let Stu go back to work. I walk amongst the patrons—greeting regulars and adjusting any chairs that are out of place. The rest of the family is upstairs preparing for Friday dinner. It’s our tradition to eat our own food at the restaurant and make a huge show of it. My father says it’s a brilliant marketing maneuver, but I think he does it so he can somehow write off a weekly dinner as a tax expense. He’ll often invite friends, family, and clients to these dinners, so it’s mostly a combination of business, gossip, and cumin. Thankfully, it’s just the family tonight. Confronting my family is going to be relatively easier when less people are around.

I walk up the creaky stairs to the second floor. Youssef was supposed to fix the rail weeks ago but claims it’s not as bad as I think it is. I tried to explain it’s a lawsuit waiting to happen: a broken rail means a broken neck. Still, as I go up the stairs, I try my best not to put too much pressure on it. Tomorrow, I’ll probably buy some extra dowels and drill some supports. No, I immediately tell myself, it’s Youssef’s responsibility, and I can’t keep fixing everything. At the top of the stairs, I stop and brace myself against the rail. Thankfully, it doesn’t give way. You can do this, I say to myself. I try breathing again, but the smoke is too distracting.

Upstairs is empty, except for my family at the large table in the back. In the center of the table is filled with couscous, tagine, tanjia, zaalouk, briouats, and whatever specials the head chef decided to experiment with. The whole room needs renovation—especially air circulation—but no one seems to care. The place is old, and that’s part of the charm. At least, that’s what my family tells me. I don’t find it that charming.

“Samira, my sweet!” my father exclaims, “Come sit next to me.”

“Oh, so she has the honor?” my mother says, mockingly.

“Yes, she figured out where the missing five hundred dollars went in the spreadsheet.”

“Please don’t bring that up,” Youssef says.

“Not once did you consider adding in all the tips we give to our drivers,” my father replies in a light, scolding tone. I typically would have enjoyed this revenge, but I don’t feel anything this time around.

“It’s nothing,” I quickly add. “I added a new row called Gratuity, so it won’t happen again.”

“Well done, my sweet.”

“Did you wash your hands?” my mother asks.

“Yes, like ten minutes ago.”

“Samira! When I was your age, my parents would chastise me for not using the washing basin.”

“Well, you’re in the US now and you’ve been here for a while,” I snap. The rest of the family freezes. I didn’t expect the conversation to get this awkward this quickly, but it is probably best to get it over with.

“Is everything alright, my sweet?” my father asks, concerned.

“No,” I say. My heart pounds harder than the construction outside. For years, I’ve wanted to escape this town, and now I finally have the chance. I feel the family guilt covering and smothering me. I can’t wash it off. I chicken out.

“Sorry, I have a headache. Let’s eat.”

“I do not understand. You are never like this,” whispers my father. His eyes soften, and he looks down at his plate.

“It’s fine,” says Youssef, “she’s fine. Please, let’s eat. I need to entertain the Benalis in like forty-five minutes. Should be a good time, they always are.”

“Ah, Fatima is so lovely of a girl,” exclaims my mother, “I remember back when—”

“Samira, you will tell me what is wrong.” My father does not raise his voice. He never has to. He has always chosen his words carefully and deliberately. Each syllable has weight and by the time he finishes the sentence, I am encumbered.

I want nothing more than to run downstairs and back to the fresh air outside. For weeks, I’ve dreaded this moment, and I’ve always made excuses. But I need to respond tonight or else they would take back their offer.

“I was offered a job.” I say, eying the couscous instead of my father.

My brother erupts in laughter. “I knew it! That’s why you quit smoking. It was probably for a drug test or something.”

“Is this true?” says my mother. She puts her hand on mine.

“I don’t think they can drug test for cigarettes.”

“No, you idiot,” adds my brother. “The job offer!”

“Pay no mind to those offers,” responds my father. “I know they are tempting, but you are happy with what you have been provided.”

This sets me off. I think about the smoke-filled rooms, broken computers, busted railings, and old wood that is rebranded as cultured. I need something else. I need to leave.

“I start Monday.”

It does not matter that the restaurant is packed below. A deafening silence fills the room above.

“Doing what?” my brother asks, more intrigued than angry. He has a slight grin on his face.

“A manager role at Le Jardin. I’ll be responsible for overall operations as well as financial performance.”

“Le Jardin,” my mother says, feigning that she’s about to pass out. “They make terrible bread.”

“Samira, you will not leave,” orders my father, “I forbid it.”

“Oh really,” I say, standing up from the table. “Ab, you are a wonderful father, but a terrible owner. This place needs to change, and you won’t let me try.”

“Then tell me what you want changed,” my father says, his eyes hollow.

“I’ve told you for years, and the fact that you can’t remember anything says it all. I’ll write an official resignation for your records tomorrow.”

I can’t bear to look into their eyes anymore, so I rush down the stairs. Without thinking, I lean heavily on the railing. With a low groan, the railing gives way and tips slowly forward. I tumble to the ground. For a moment, I am dazed, but then Stu lightly slaps my cheek. When I come to, I see my family looking down at me from the second floor. I feel so far away from them. With no broken bones, I stand up and dash outside. Stu follows me.

In the crisp clean air, I turn to Stu and reach into his pocket. From it I pulled out his pack of smokes. I pull the butt to my lips and instinctively reach for my lighter. There is none there.

“Stu, your lighter.” I order.

“I thought you quit, I heard everything. You can’t give me orders.”

“I haven’t handed in my resignation yet, so give me your lighter or you’re fired.”

Stu laughs bitterly, “Sure thing, Sammy.”

Desperately, I grab the lighter and watch the butane fluid burn a flame. The light flickers in the wind but remains. Before I put the light to my end of the cigarette, I toss the cigarette and lighter on the ground. Am I actually going to leave my family? This restaurant? Will it even survive when I’m gone?

“You know I wouldn’t fire you, right?”

“Technically, you can’t. That’s your father’s responsibility.”

“Well, maybe I can persuade you to join Le Jardin.”

“I’ll stay here. You taught me well.”

Stu picks up his lighter, pats me on the back, and walks back into the restaurant.

Now, I am alone.