7.1: Organizing Research Plans

- Page ID

- 54261

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)| LEARNING OBJECTIVES |

| 1. Know how to begin a research project by examining the assignment closely and considering the genre(s) you will use. 2. Understand how to make decisions about how and where you will research, what genre(s) you will use for writing, and how you will track your sources. 3. Know how to create a schedule and understand how to start and use a research log. |

In Chapter 5 "Planning" and Chapter 6 "Drafting", you learned about choosing and narrowing a topic to arrive at a thesis, and you learned that once you have a thesis, you can plot how you will accomplish your rhetorical purposes and writing goals. But sometimes just coming up with a thesis requires research—and it should. Opinions are cheap; theses are not. Remember how important it is to be flexible; plans can change, and you need to be prepared for unexpected twists and turns during the research process. Making decisions about the issues in this chapter will give you a solid beginning toward conducting research that is meaningful to you and to your readers.

Revisiting Your Assignment

As you prepare to start researching, you should review your assignment to make sure it is clear in your mind so you can follow it closely. Some assignments dictate every aspect of a paper, while others allow some flexibility. Make sure you understand the requirements and verify that your interpretations of optional components are acceptable.

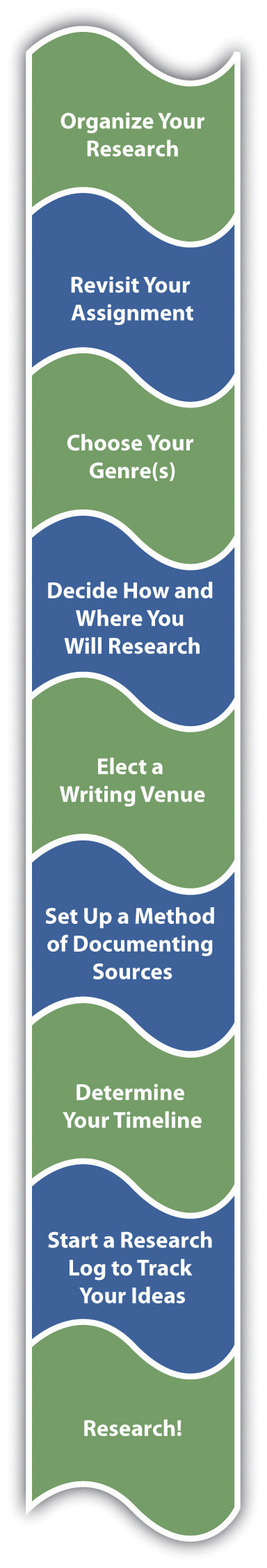

Figure 7.1

Choosing Your Genre(s)

Clarify whether your assignment is asking you to inform, to interpret, to solve a problem, or to persuade or some combination of these four genres. This table lists key imperative verbs that match up to each kind of assignment genre.

| Key Words Suggesting an Informative Essay | Key Words Suggesting an Interpretive Essay | Key Words Suggesting a Persuasive Essay | Key Words Suggesting a Problem-Solving Essay |

| • Explain • Define • Describe • Review |

• Classify • Analyze • Compare • Examine • Explain |

• Interpret • Defend • Determine • Justify • Refute |

• Take position • Alleviate • Assess • Ease • Propose • Solve |

If the assignment does not give you a clear idea of genre through the imperative verbs it uses, ask your instructor for some guidance. This being college, it’s possible that genre, like some other matters, is being left up to you. In such a scenario, the genre(s) you adopt will depend on what you decide about your purposes for writing. The truth is, genres blend into each other in real writing for real audiences. For example, how can you “take a position” about a social issue like teen pregnancy without doing some reporting and offering some solutions? How can you offer solutions to problems like climate change without first reporting on the severity of the problem, arguing for the urgency of the need for solutions, arguing that your solution is the best of several proposals, and finally arguing for your solution’s feasibility and cost effectiveness?

Take the case of Jacoba, who is given the following inquiry-based research1 assignment, a genre of academic writing that is becoming increasingly common at the college level:

In an essay of at least twenty-five hundred words, I want you to explore a topic that means something to you but about which you do not yet have a clear opinion. Unlike other “research papers” you may have been asked to write in the past, you should not have a clear sense of your position or stance about your topic at the outset. Your research should be designed to develop your thinking about your topic, not to confirm an already held opinion, nor to find “straw men” who disagree with you and whose ideas you can knock down with ease.

| 1. A type of assignment requiring exploration of a topic about which the student does not have a prior opinion. |

Make no mistake, by the end of this process, if you have chosen a topic about which you’re really curious and if you research with an open mind, you will have plenty to say. The final product may be submitted in any number of forms (possibilities include an interpretive report, a problem-solving proposal, a manifesto-like position statement) but it must be grounded in source work and it must demonstrate your ability to incorporate other voices into your work and to document them appropriately (using MLA standards). And like any other writing we have done in this course so far, you are responsible for determining the audiences you want to reach and the purposes you want to achieve.

In this assignment, Jacoba and her classmates are intentionally given very little direct guidance and very few explicit instructions from their instructor about how to proceed. After some class discussion and some initial brainstorming on her own, she decides he wants to research and write about the crisis in solvency in Social Security. Prior to researching, she isn’t exactly sure how she feels about the issue, much less about an appropriate audience or purpose. She just knows she’s worried about her own aging parents and feels they deserve what’s coming to them. At the same time, she’s rankled that, in her early twenties, she has no expectation of ever seeing any of the money that’s been coming out of her paycheck every two weeks. The combination of uncertainty and interest she feels about the topic actually makes it ideal for this kind of inquiry-based research project.

Using the tips in Chapter 4 "Joining the Conversation", Jacoba puts together two preliminary statements of purpose intentionally at odds with each other.

Table 7.1 Statement of Purpose I

| Voice | I am writing as a daughter and young adult. |

| Message | I want to convey the message that we need to come up with realistic solutions for how Social Security needs to be fixed. |

| Audience | I want to write to people my parents’ age: 55 years old and up. |

| Attitude | My attitude toward the subject is positive toward Social Security and what it has meant to this country since the Great Depression. |

| Reception | I want my audience to have the tools they need to mobilize support for saving Social Security, for themselves, and for my generation. |

| Tone | My tone toward my readers will be concerned but determined to find solutions. |

Table 7.2 Statement of Purpose II

| Voice | I am writing as a concerned and informed citizen and voter. |

| Message | I want to convey the message that we need to come to terms with the fact that Social Security has outlived its usefulness and must be gradually phased out. |

| Audience | I want to write to members of Congress eager to reduce the size of government. |

| Attitude | My attitude toward the subject is negative toward the strain Social Security is placing on our budget deficit. |

| Reception | I want my audience to have the tools they need to persuade their colleagues in Congress to develop the political will to phase out Social Security. |

| Tone | My tone toward my readers will be respectful but assertive and persuasive. |

Jacoba knows that these are just two of the possible purposeful paths she may take over the course of her research process. A change to any of the six elements of her chart will mean writing up another statement of purpose. Using a research log, she will periodically reflect on how each of the elements of her preliminary statements of purpose are affected by each new source she encounters.

Deciding How and Where You Will Research

Although you might think that you can accomplish all of your research online from the comfort of your home, you should at least begin by visiting your school library. Talk to a research librarian about your planned paper and get his or her advice. You will likely learn about some in-library sources that would be helpful. But you will also probably discover some online sources and procedures that will be very beneficial. Another technique you can use for learning about research options is to talk to fellow students who have recently completed research projects. As always, you might be surprised what you can learn by such networking. Primary sources2, such as in-person interviews and observations, can add an interesting dimension to a researched essay. Determine if your essay could benefit from such sources.

Selecting a Writing Venue

Your writing venue might be predetermined for you. For example, you might be required to turn in a Microsoft Word file or you might be required to work on an online class site. Before you start, make sure you know how you will be presenting your final essay and if and how you are to present drafts along the way. Having to reroute your work along the way unnecessarily wastes time.

Setting Up a Method of Documenting Sources

You will need to document your sources as you research since you clearly do not want to have to revisit any of your sources to retrieve documentation information. Although you can use the traditional method of creating numbered source cards to which you tie all notes you take, it makes much more sense to create digital note cards. Most college library databases include options for keeping a record of your sources. Using these tools can save you time and make the research process easier. Such sites also allow you to take notes and tie each note to one of the citations. Make sure to explore the services that are available to you. If you haven’t seen a college library database in some time, you will be pleasantly surprised at all the time-saving features they provide.

You can also create your version of digital note cards simply by making a file with numbered citations and coding your notes to the citations. If you choose, you can go online and find a citation builder3 for assistance. Once you put a source’s information into the builder, you can copy and paste the citation into your citation file and into the citation list at the end of your paper. Your college library’s databases include tools that will help you build citations in American Psychological Association (APA), Modern Language Association (MLA), or other styles. Similar tools are also available with no college or university affiliation, but these tend to have ad content and can sometimes be less reliable. Another, less commercial option is an online writing lab (OWL)4. OWLs are college-level writing instruction sites managed by university writing programs and usually open to public use. The most famous and, according to many, still the best, is managed by the Purdue Writing Program: http://owl.english.purdue.edu. Bookmark this site on your computer for the rest of your college career. You won’t regret it.

|

2. Firsthand source (e.g., in-person interviews and observations). 3. Online tool into which you can plug source information and receive a properly written citation in a chosen documentation style. 4. A university-sponsored, ad-free, free-to-use site full of writing instructions. |

Determining Your Timeline

Begin with the amount of time you have to complete your project. Create a research and writing schedule that can realistically fit into your life and allow you to generate a quality product. Then stick with your plan. As with many time consuming tasks, if you fall off your schedule, you are likely to find yourself having to work long hours or having to make concessions in order to finish in time. Since such actions will probably result in an end product of lesser quality, making and keeping a schedule is an excellent idea.

As a rule, when you make a schedule, it is best to plan to spend a little time each day as opposed to long blocks of time on a few days. Although, on a long project, you might find it beneficial to have some lengthy days, as a rule, long hours on a single project do not fit into one’s daily life very well.

As you schedule your time, plan for at least one spare day before the project is due as sort of an insurance policy. In other words, don’t set your schedule to include working through the last available minute. A spare day or two gives you some flexibility in case the process doesn’t flow along perfectly according to your plan.

If you plan to have others proofread your work, respectfully consider their schedules. You can’t make a plan that requires others to drop what they are doing to read your draft on your schedule.

Starting a Research Log to Track Your Ideas

A research log is a great tool for keeping track of ideas that come to you while you are working. For example, you might think of another direction you want to pursue or find another source you want to follow up on. Since it is so easy to forget a fleeting but useful thought, keeping an ongoing log can be very helpful. The style or format of such a log will vary according to your personality. If you’re the type of person who likes to have a strict timeline, the log could be a chronologically arranged to-do list or even a series of alarms and reminders programmed into your cell phone. If, on the other hand, you’re a bit more conceptual or abstract in your thinking, keeping an up-to-date statement of purpose chart might be the way to go.

| KEY TAKEAWAYS |

| • When preparing to start a research paper, revisit your assignment to make sure you understand and remember all the guidelines. Then choose the writing genre that best fits the assignment guidelines and your statement of purpose. In some cases, you may elect to use a mix of writing to inform, to interpret, to persuade, and to solve a problem. • As a rule, you should begin your research with a meeting with a college librarian to make sure you are aware of your research options. Also, as you begin a research project, you have to decide whether you will use a simple word processing document or a more complex format, such as an online class site set up by your instructor. At the very beginning of a project, you should also make a plan for documenting your sources so that you are organized from the start. • Based on the desired length of your essay and the amount of research you have to do, plan a realistic schedule that you can follow. Create a research log to keep track of information you want to remember and address as you research. |

| EXERCISES |

|

1. Describe your research plans for this sample assignment: In ten to fourteen pages, compare the leisure activities that would have been typical of your ancestors prior to coming to the United States to your current-day leisure activities. Upload each version of your work to the class site for peer editing and review. The final version of the project is due to File Exchange in three weeks. Include essay genre and length, how and where you will research, your writing venue, a method of documenting sources, and a day-by-day timeline. 2. Describe your research plans for this assignment: In eight to ten double-spaced pages, take a stand on gay marriage and defend your position. Turn in a hard copy of your essay at the beginning of class one week from today. Include essay genre and length, how and where you will research, your writing venue, a method of documenting sources, and a day-by-day timeline. 3. Describe your research plans for this assignment that is due at the end of the semester: Work with a team of four to six people and create an online collaboration site. Each of you should choose a different topic related to technology benefits and review the related information. Complete your first draft with at least four weeks left in the semester. Then have each of your teammates review and make suggestions and comment. Complete all peer reviewing prior to the last two weeks of the semester. Gather all the reviews and make edits as desired. Limit your final paper to thirty pages and publish it on the class site by the last day of the semester. Include essay genre and length, how and where you will research, your writing venue, a method of documenting sources, and a day-by-day timeline. 4. For each of the above projects, work with your writing group to develop at least one preliminary statement of purpose (indicating voice, audience, message, tone, attitude, and reception). Then change at least one element of the six and revise the statement of purpose accordingly. (See Chapter 5 "Planning" for more on compiling a statement of purpose.) |