5.3: Developing Your Purposes for Writing

- Page ID

- 54237

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)| LEARNING OBJECTIVES |

| 1. Know how to identify the ideal voice, audience, and message for a given topic. 2. Explore the multiple purposes you have for writing. 3. Recognize how your writing process depends on the relationship between voice and message (attitude), message and audience (reception), and voice and audience (tone). 4. Learn how to use a statement of purpose as a tool for strategizing about, reflecting on, and presenting your work. |

After you have settled on a specific writing topic, it’s time to return to some of the basic principles of rhetoric introduced in Chapter 4 "Joining the Conversation" so that you can think through your real purposes for writing and explore the key details of your rhetorical situation. This section will show you how to use both the corners and the sides of the rhetorical triangle as tools for thinking, planning, and writing. Notice how these choices you make about purpose, message, audience, and voice are never made in isolation.

• Purpose8: You may think that purpose can be boiled down to one of these single verbs or phrases:

◦ To analyze

◦ To ask for support

◦ To call to action

◦ To clarify

◦ To convince

◦ To counter a previously stated opinion

◦ To describe

◦ To entertain

◦ To inform

◦ To make a request

◦ To make people think

◦ To persuade

◦ To share feelings

◦ To state an opinion

◦ To summarize

| 8. The sum total of what a writer intends to accomplish. |

However, your real purposes for writing are really more complicated, interesting, and dynamic than this simple list. Purpose involves all three sides and all three corners of the rhetorical triangle: not only do you want to make your audience feel or think a certain way about your message, but you also want to explore and refine your own thoughts and feelings about that message, and furthermore, you want to establish a certain kind of relationship with your audience through the act of conveying your message to them.

• Audience9: Sometimes your instructor will specify the audience for an essay assignment, but more often than not, this choice will be left up to you. If it’s your call, ask yourself, “Who would benefit the most from receiving this message?” Not asking that simple question, not choosing a specific audience for your essay, will be a missed opportunity to sharpen your skills as a communicator. By identifying your audience, you can conjecture how much your readers will know about your topic and thus gauge the level of information you should provide. You can determine what kind of tone10 is best for your audience (e.g., formal or informal, humorous or serious). Based on what you know about your audience, you can even decide the form you want your writing to take (e.g., whether to write a descriptive or more persuasive essay). Knowing your audience will guide many of the other choices you make along the way.

• Message11: Regardless of whether your topic is assigned to you or you come up with it on your own, you still have some room to develop your message. Be prepared to revise your message once you have fleshed out your own thinking about it (perhaps through asking and answering the Twenty Questions about Self, Text, and Context in Chapter 1 "Writing to Think and Writing to Learn") and sharpened your sense of audience and purpose thinking.

• Voice12: Regardless of whether you’re writing in an academic or a nonacademic context, you draw from a range of voices to achieve a variety of purposes. Each of the purposes listed above has an appropriate voice. If you are writing an essay to fulfill a class assignment, with your instructor as your primary if not exclusive audience, then your voice has pretty much been established for you. In such an instance, you are a student writing in a traditional academic context, subject to the evaluation of your instructor as an expert authorized to judge your work. But even in this most restrictive case, you should still try to develop a distinctive voice based on what you hope to accomplish through your writing.

|

9. The reader(s) of an essay or a piece of communication. 10. The relationship between the voice (writer) and the audience (readers). 11. What a voice (writer) wants to convey about a topic to an audience (readers). 12. The writer of an essay or a piece of communication. |

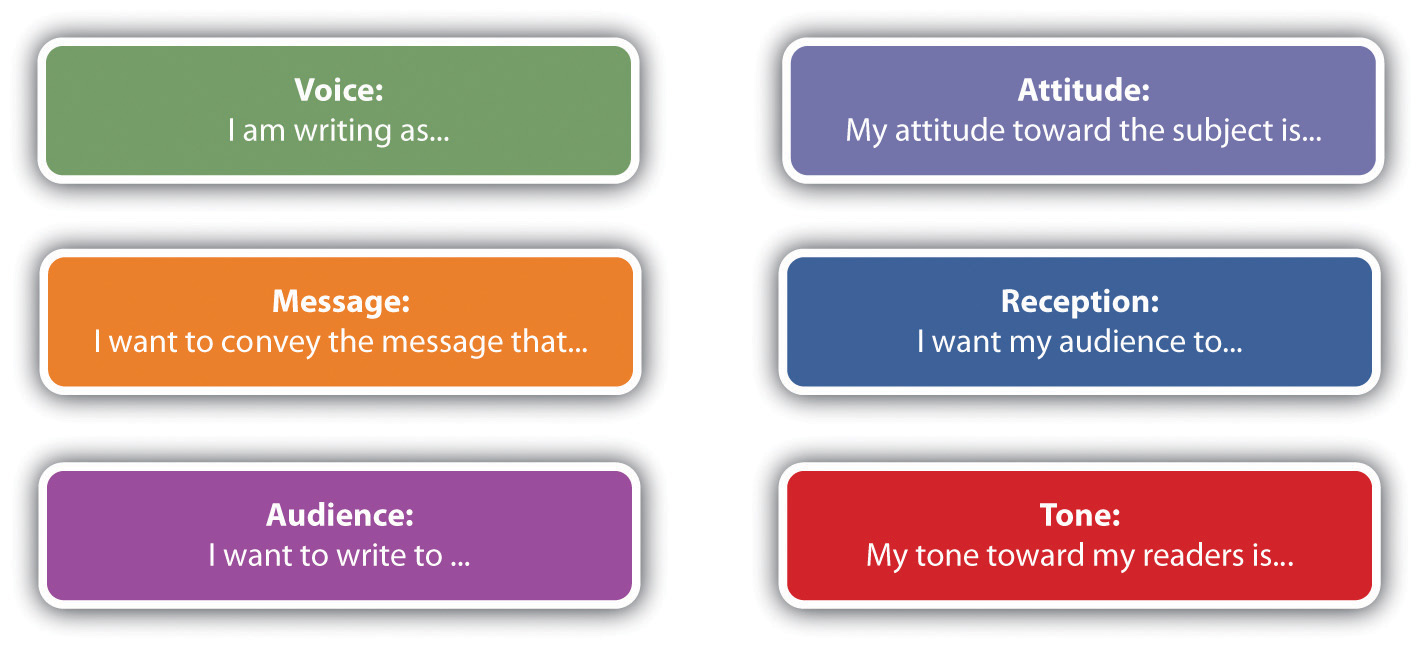

Once you have identified your purposes and the corners of the rhetorical triangle, it’s time to do some preliminary thinking about the relationships between those corners—that is, the sides: voice and message (attitude), message and audience (reception), and voice and audience (tone). Finish the sentences below.

Figure 5.2 Your Rhetorical Situation

Near the beginning of the writing project, you could write up a preliminary statement of purpose13 based on how you complete these sentences and use it as a strategy memo of sorts:

| Voice | I am writing as a person unfamiliar with South Dakota culture who has been assigned the task of writing about it. |

| Message | I want to convey the message that the Sturgis Motorcycle Rally is an interesting phenomenon of popular culture. |

| Audience | I want to write to my teacher and the other members of my writing group. |

| Attitude | My attitude toward the subject is pretty neutral right now, bordering on bored, until I find out more about the topic. |

| Reception | I want my audience to know that I know how to research and write about any topic thrown at me. |

| Tone | My tone toward my readers is semiformal, fairly objective, like a reporter, journalist, or anthropologist. |

Because all the elements of the triangle are related to each other, all are subject to change when the direction of your work changes, so be open to the idea of returning to these questions several times over the course of your writing project. When you are ready to turn in your project, revise your preliminary statement of purpose into a final version, or writer’s memo14, as a way of presenting and packaging your project, especially if your instructor invites such reflection and

commentary.

|

13. A preliminary tool for developing your purposes for a writing project, specifically your message, audience, voice, attitude, reception, and tone. 14. A method of presenting, packaging, reflecting on, and commenting on one’s own writing project, specifically its message, audience, voice, attitude, reception, and tone. |

Here’s an example of a writer’s memo submitted with the Sturgis Motorcycle Rally essay:

| Voice | I am writing as a kind of social historian and observer of a specific example of popular culture. |

| Message | I want to convey the message that the Sturgis Motorcycle Rally has become an important part of the identity of Sturgis and the surrounding area. |

| Audience | I want to write to my instructor and classmates—but also to the citizens of Sturgis, South Dakota. |

| Attitude | My attitude toward the subject is neutral to positive. In general I think the rally has been good for Sturgis over the years. |

| Reception | I want my audience to understand and appreciate Sturgis Motorcycle Rally, and maybe to think about how something like it could work well in our community. |

| Tone | My tone toward my readers will be informal but informative, and occasionally humorous, to fit the craziness of Sturgis Motorcycle Rally. |

| KEY TAKEAWAYS |

| • When completing a class assignment, your instructor will often dictate a required writing form. When you are able to choose your own writing form, you should choose a form that you think would work well for your planned writing. • Understanding your audience allows you to gauge the level of information you should provide, choose a tone you want to use, and decide the approach you want to take. • Your purposes for writing include what you want to learn about your own message, how you want your audience to receive your message, and the kind of working relationship you want to establish with your audience. |

| EXERCISES |

| 1. Describe five possible topics you could use as the basis for an opinion essay. 2. You are to writing an essay that is a call to action. List five topics you could write about. 3. You are being asked to describe an important event in your childhood. What form of writing from the list in this section would be most appropriate? 4. You are writing a letter of application for a college scholarship sponsored by a local business. For what audiences would you write the letter? 5. You are writing an opinion essay and submitting it as a letter to the editor at your local newspaper. For what audiences would you write this letter? 6. From the list of purposes in this section, choose a purpose that would match this assignment: Write a letter to the editor for the school paper detailing why your classmates should vote for you for class president. 7. With your writing group, use the statement of purpose questions to sketch out the details on voice, message, audience, attitude, reception, and tone for the writing ideas you generated for Question 1 and Question 2 above. |