2.6: The Internet- The Researcher’s Challenge

- Page ID

- 6473

Along with the distinction between primary and secondary sources and the distinction between scholarly and non-scholarly publications, you now need to consider a relatively new type of research source as you gather your evidence: the Internet, particularly the World Wide Web. The Internet started up almost 30 years ago, and elements like electronic mail (“email”) and bulletin board newsgroup discussions have been around for quite some time.

Widespread use of the Internet really took off in the early 1990s with the development of the World Wide Web and browser software like Mosaic, Netscape, and Internet Explorer. In fact, the Web has become such a powerful research resource that many beginning research writing students wonder why they should go to the library at all.

Hyperlink: See the section “What’s ‘a library?’ & ‘What’s The Internet?’” in Chapter 2, “Understanding and Using the Library and the Internet for Research."

The Web has become such a powerful medium in part because it has such a far reach—literally, anyone anywhere in the world who is connected to the World Wide Web with the right computer and the right software can access almost any of the hundreds of millions of “pages” and other documents on the Web. But it also has grown so quickly because it is relatively easy to put documents on to the Web. In fact, you too might consider exploring some of the options through your school or through a commercial service for joining the World Wide Web community by publishing your research project on the Web.

Hyperlink: See the section “The Web-based Research Project” in Chapter 11, “Alternative Ways to Present Your Research.”

Nowadays, the Web has become dominated by corporate and “mainstream” sites that are advertised on television and in traditional magazines and newspapers, which means that it is difficult for an individual’s Web site to compete with the Web sites of The New York Times or amazon.com. But individuals can still publish their own Web sites, and individually published Web sites can still attract a large and international audience.

Indeed, one of the great strengths of the World Wide Web is that just about anyone can put up “professional looking” Web pages that can reach a potential audience of millions. However, this strength of the Web is also its weakness, at least as far as being a good place to look for research because anyone can publish what appears to be a “professional” Web site, regardless of his or qualifications.

This fact means the Web is significantly different from more traditional sources of research. Most scholarly publications are closely scrutinized by editors and other scholars within a particular field. Further, the articles that appear in even the most non-scholarly of popular sources pass through a variety of different writers and editors before they make it to press.

The problem with many Web pages is that the review process and editors that we assume to be in place with traditional print sources are simply not there. For example, it would be easy for me to fabricate a Web site (complete with charts, graphs, and fake statistics) that argued that students and teachers who used this textbook became more fit, richer, and better-looking. Such inaccurate claims would never pass the review process of a scholarly journal or a popular magazine--with the possible exception of the sort of tabloid we all see at the grocery store check-out that reports on Elvis sightings. But on the Web, it is just another page which, if someone finds it “believable,” could be included in someone’s research writing.

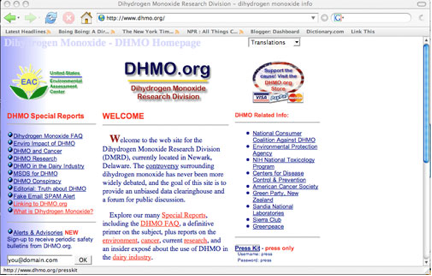

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\) - The Dihydrogen Monoxide Research Division web site, <http://www.dhmo.org>, certainly looks like an official and reliable web site. What seems to make it a bit suspect? What exactly is Dihydrogen Monoxide, anyway?

More seriously, many deceptive and “professional” looking Web pages present very inaccurate and misleading information and they are not intended to be jokes. Some of these pages are the work of various hate groups—racists or Holocaust deniers, for example—and some of these sites seem to be the work of con artists. But when these sites are read uncritically, they can cause serious problems for academic researchers.

Of course, not everything you find on the Web is untrustworthy. Far from it. For one thing, the lines between what counts as an Internet source and a more traditional “print” source are beginning to blur. There are numerous online databases available in many libraries that have complete text versions of articles from academic and popular periodicals, and the articles from these databases are every bit as reliable as the traditional print sources.

Hyperlink: See the discussion about electronically available periodicals in the section “Journals, Magazines, and Newspapers” in Chapter 2, “Understanding and Using the Library and the Internet for Research.”

Additionally, more and more traditional print sources are creating and maintaining Web sites. Almost all of the most popular news magazines, newspapers, and television networks have Web pages that either reproduce information available in more traditional formats or that publish articles specifically for the Web. More and more scholarly publications are becoming available on the Web as well, and considering the international reach and low cost of publishing on the Web, it seems inevitable that more (maybe most) academic journals will eventually move from being traditional print journals to ones available only online.

Conversely, not everything you find in traditional print publications—either scholarly or non-scholarly—is always accurate and truthful. Despite the safeguards that most academic and popular publications follow to ensure they publish truthful and accurate articles, there are all sorts of examples of inaccuracies in print.

More common and therefore perhaps more problematic, small errors and misrepresentations appear in both academic and popular sources, evidence that the process of editorial review is not perfect. And what “counts” as true or accurate in many fields is a question of some debate and uncertainty, and this is frequently reflected in published articles of all sorts.

Here’s my point: as I will discuss in the next section of this chapter, the best way to ensure that your evidence is reliable, regardless of where you found that evidence, is to seek out a variety of different types of evidence and to think critically about the quality and credibility of your sources. This is particularly true with Web-based research.

Exercise 1.4

Working alone or collaboratively in small groups, consider the following questions:

- Think of a web site that you visit on a regular basis. What makes this site a useful and credible resource for you?

- Are there any Web sites that you have come across that you thought were not believable or credible? Why did you find this site not believable?