6.1: A beginner's guide

- Page ID

- 67074

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Introduction to the Middle Ages

The dark ages?

So much of what the average person knows, or thinks they know, about the Middle Ages comes from film and tv. When I polled a group of well-educated friends on Facebook, they told me that the word “medieval” called to mind Monty Python and the Holy Grail, Blackadder, The Sword in the Stone, lusty wenches, feasting, courtly love, the plague, jousting and chain mail.

Perhaps someone who had seen (or better yet read) The Name of the Rose or Pillars of the Earth would add cathedrals, manuscripts, monasteries, feudalism, monks and friars.

Petrarch, an Italian poet and scholar of the fourteenth century, famously referred to the period of time between the fall of the Roman Empire (c. 476) and his own day (c. 1330s) as the Dark Ages.

Petrarch believed that the Dark Ages was a period of intellectual darkness due to the loss of the classical learning, which he saw as light. Later historians picked up on this idea and ultimately the term Dark Ages was transformed into Middle Ages. Broadly speaking, the Middle Ages is the period of time in Europe between the end of antiquity in the fifth century and the Renaissance, or rebirth of classical learning, in the fifteenth century and sixteenth centuries.

Not so dark after all

Characterizing the Middle Ages as a period of darkness falling between two greater, more intellectually significant periods in history is misleading. The Middle Ages was not a time of ignorance and backwardness, but rather a period during which Christianity flourished in Europe. Christianity, and specifically Catholicism in the Latin West, brought with it new views of life and the world that rejected the traditions and learning of the ancient world.

During this time, the Roman Empire slowly fragmented into many smaller political entities. The geographical boundaries for European countries today were established during the Middle Ages. This was a period that heralded the formation and rise of universities, the establishment of the rule of law, numerous periods of ecclesiastical reform and the birth of the tourism industry. Many works of medieval literature, such as the Canterbury Tales, the Divine Comedy, and The Song of Roland, are widely read and studied today.

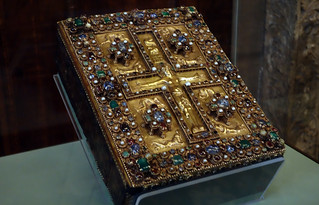

The visual arts prospered during Middles Ages, which created its own aesthetic values. The wealthiest and most influential members of society commissioned cathedrals, churches, sculpture, painting, textiles, manuscripts, jewelry and ritual items from artists. Many of these commissions were religious in nature but medieval artists also produced secular art. Few names of artists survive and fewer documents record their business dealings, but they left behind an impressive legacy of art and culture.

Byzantium

When I polled the same group of friends about the word “Byzantine,” many struggled to come up with answers. Among the better ones were the song “Istanbul (Not Constantinople)” sung by They Might Be Giants, crusades, things that are too complex (like the tax code or medical billing), Hagia Sophia, the poet Yeats, mosaics, monks, and icons. Unlike Western Europe in the Middle Ages, the Byzantine Empire is not romanticized in television and film.

In the medieval West, the Roman Empire fragmented, but in the Byzantine East, it remained a strong, centrally-focused political entity. Byzantine emperors ruled from Constantinople, which they thought of as the New Rome. Constantinople housed Hagia Sophia, one of the world’s largest churches, and was a major center of artistic production.

The Byzantine Empire experienced two periods of Iconoclasm (730-787 and 814-842), when images and image-making were problematic. Iconoclasm left a visible legacy on Byzantine art because it created limits on what artists could represent and how those subjects could be represented. Byzantine Art is broken into three periods. Early Byzantine or Early Christian art begins with the earliest extant Christian works of art c. 250 and ends with the end of Iconoclasm in 842. Middle Byzantine art picks up at the end of Iconoclasm and extends to the sack of Constantinople by Latin Crusaders in 1204. Late Byzantine art was made between the sack of Constantinople and the fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Turks in 1453.

In the European West, Medieval art is often broken into smaller periods. These date ranges vary by location.

c.780-900 – Carolingian Art

c.900-1000 – Ottonian Art

c.1000-1200 – Romanesque Art

c.1200-1400 – Gothic Art

Additional resources:

Byzantium from The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Icons and Iconoclasm on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Hagia Sophia on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

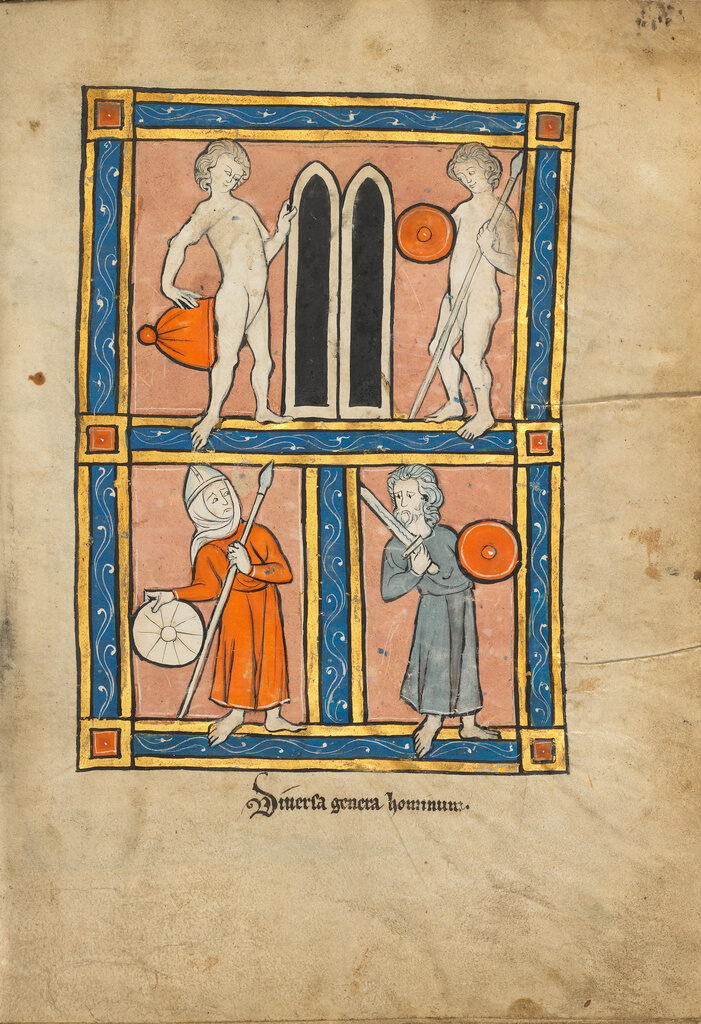

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

A new pictorial language: the image in early medieval art

An illusion of reality

Classical art, or the art of ancient Greece and Rome, sought to create a convincing illusion for the viewer. Artists sculpting the images of gods and goddesses tried to make their statues appear like an idealized human figure. Some of these sculptures, such as the Aphrodite of Knidos by Praxiteles, were so lifelike that legends spread about the statues coming to life and speaking to people. After all, a statue of a god or goddess in the ancient world was believed to embody deity.

The problem for early Christians

The illusionary quality of classical art posed a significant problem for early Christian theologians. When God dictated the ten commandments to Moses on Mount Sinai, God expressly forbade the Israelites from making any graven image, or any likeness of any thing that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth (Exodus 20:4). Early Christians saw themselves as the spiritual progeny of the Israelites and tried to comply with this commandment. Nevertheless, many early Christians were converted pagans who were accustomed to images in religious worship. The use of images in religious ritual was visually compelling and difficult to abandon.

Tertullian asks: Can artists be Christians?

Tertullian, an influential early Christian author living in the second and third centuries, wrote a treatise titled On Idolatry in which he asks if artists could, in fact, be Christians. In this text, he argues that all illusionary art, or all art that seeks to look like something or someone in nature, has the potential to be worshiped as an idol. Arguing fervently against artists as Christians, he acknowledges that there are many artists who are Christians and indeed some who are even priests. In the end, Tertullian asks artists to quit their work and become craftsmen.

Augustine: Illusionary images are lies

Another influential early Christian writer, St. Augustine of Hippo, was also concerned about images, but for different reasons. In his Soliloquies (386-87), Augustine observes that illusionary images, like actors, are lying. An actor on a stage lies because he is playing a part, trying to convince you that he is a character in the script when in truth he is not. An image lies because it is not the thing it claims to be. A painting of a cat is not a cat, but the artist tries to convince the viewer that it is. Augustine cannot reconcile these lies with patterns of divine truth and therefore does not see a place for images in Christian practice.*

Fortunately for art and history, not everyone agreed with Tertullian and Augustine and the use of images persisted. Nevertheless their style and appearance changed in order to be more compatible with theology.

Towards abstraction (and away from illusion)

Christian art, which was initially influenced by the illusionary quality of classical art, started to move away from naturalistic representation and instead pushed toward abstraction. Artists began to abandon classical artistic conventions like shading, modeling and perspective conventions that make the image appear more real. They no longer observed details in nature to record them in paint, bronze, marble, or mosaic.

Instead, artists favored flat representations of people, animals and objects that only looked nominally like their subjects in real life. Artists were no longer creating the lies that Augustine warned against, as these abstracted images removed at least some of the temptations for idolatry. This new style, adopted over several generations, created a comfortable distance between the new Christian empire and its pagan past.

In Western Europe, this approach to the visual arts dominated until the imperial rule of Charlemagne (800-814) and the accompanying Carolingian Renaissance. This controversy over the legitimacy and orthodoxy of images continued and intensified in the Byzantine Empire. The issue was eventually resolved, in favor of images, during the Second Council of Nicaea in 787.

*There is some irony here since Augustine’s position echos, to some extent, the writing of the ancient Greek philosopher Plato. In book X of The Republic (c. 360 B.C.E.), Plato describes a true thing as having been made by God, while in the earthly sphere, a carpenter, for example, can only build a replica of this truth (Plato uses a bed to illustrate his point). Plato states that a painter who renders the carpenter’s bed creates an illusion that is two steps from the truth of God.

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

An Introduction to the Bestiary, Book of Beasts in the Medieval World

by ELIZABETH MORRISON and LARISA GROLLEMOND

The bestiary — the medieval book of beasts — was among the most popular illuminated texts in northern Europe during the Middle Ages (about 500–1500). Medieval Christians understood every element of the world as a manifestation of God, and bestiaries largely focused on each animal’s religious meaning. The book brought creatures both real and fantastic to life before the reader’s eyes, offering Christian inspiration as well as entertainment.

The stories and images from the bestiary became so popular that they escaped from the book’s pages to inhabit a myriad of other art forms, ranging from magnificent tapestries to exquisitely carved ivories. In fact, the stories of the bestiary pervaded both medieval and modern popular culture. Even if you haven’t heard of the medieval bestiary, you will recognize many of its stories.

Book of Beasts: The Bestiary in the Medieval World is the first exhibition ever dedicated to the bestiary and its influence. It gathers together more than a hundred works from institutions across the United States and Europe, including one-third of the world’s surviving illuminated bestiaries. As manuscripts specialists, curators of this exhibition, and editors of the accompanying book, in this post we introduce key stories from the bestiary, describe the contents of a typical bestiary, and explore the bestiary’s centuries-long influence.

How bestiaries work — The unicorn

The unicorn offers a primary example of the bestiary’s complex symbolism, as well as its influence on both medieval and modern imaginations.

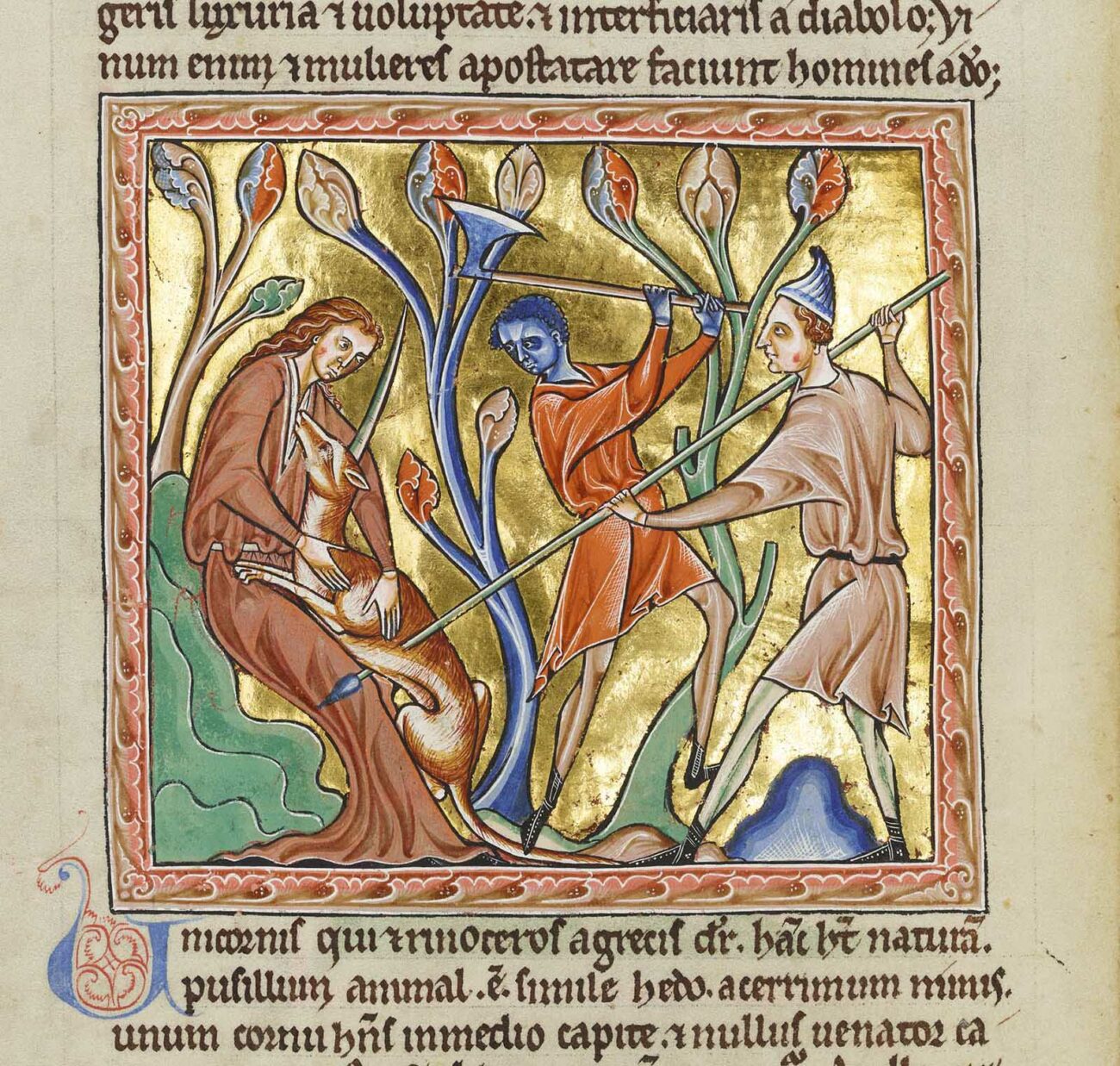

The unicorn was described in the text of the bestiary as a wild, untamable beast that could be captured only by a maiden in the woods. Upon meeting the maiden, the unicorn would lay its head in her lap, making it vulnerable to the attack of hunters.

In the bestiary, however, the unicorn’s appearance and capture were only half the story. The unicorn also symbolized the Incarnation, the moment when Christ was conceived in the womb of the Virgin Mary, rendering him human and vulnerable to death. In the luxurious image shown above, the beast rests in the lap of a maiden seated before a tree, while a hunter on the right stabs the animal in its side. The unicorn symbolizes Christ and the maiden represents his mother the Virgin Mary, while the killing of the creature serves as an allegory for Christ’s death.

The widespread diffusion of the bestiary popularized the unicorn’s tale, which was adapted in many other media in addition to manuscripts. At the center of this carved bone saddle, for example, a stately unicorn looks over its shoulder at an elegant maiden, echoing the bestiary story.

Thanks to its proclivity for maidens, the unicorn also became a focus of stories of romance and chivalry, transforming from a religious symbol into an emblem of courtly love.

Text and image in the bestiary

Medieval bestiaries contained anywhere from a few dozen to more than a hundred descriptions of animals, each accompanied by an iconic image. Some descriptions explained a creature’s Christian significance, such as the unicorn as a symbol for Christ, while others focused on physical characteristics. The selection and order of the beasts varied, though many bestiaries divided them into a hierarchy of land animals, birds, serpents, and sea creatures. The bestiary was originally intended for religious education within the church, but it was eventually sought after by wealthy members of society for devotional reading as well as entertainment.

The lion

The lion was known in the bestiary as the “king of beasts,” and as such, was placed first. In this spectacularly colorful image, a jaunty lion waves to the viewer at top. In the middle, three cubs playfully crawl over their adult counterpart. At bottom, cubs are brought to life by their parents, who lick and breathe on them. According to the bestiary, lion cubs are born dead, and after three days their parents literally breathe life into them. This behavior was believed to have been put into the lion at the beginning of time by God as a reflection of the Crucifixion of Christ and his Resurrection three days later.

Land animals

After introducing the lion, the typical bestiary presented a section devoted to land animals. According to the text in this example, the four-legged beast depicted at bottom can move its long horns independently, so that one can face forward and the other backward to defend against dual threats. The artist emphasized this flexibility by showing one of the animal’s horns slicing through the text itself. Such interaction between text and image was a hallmark of the bestiary tradition.

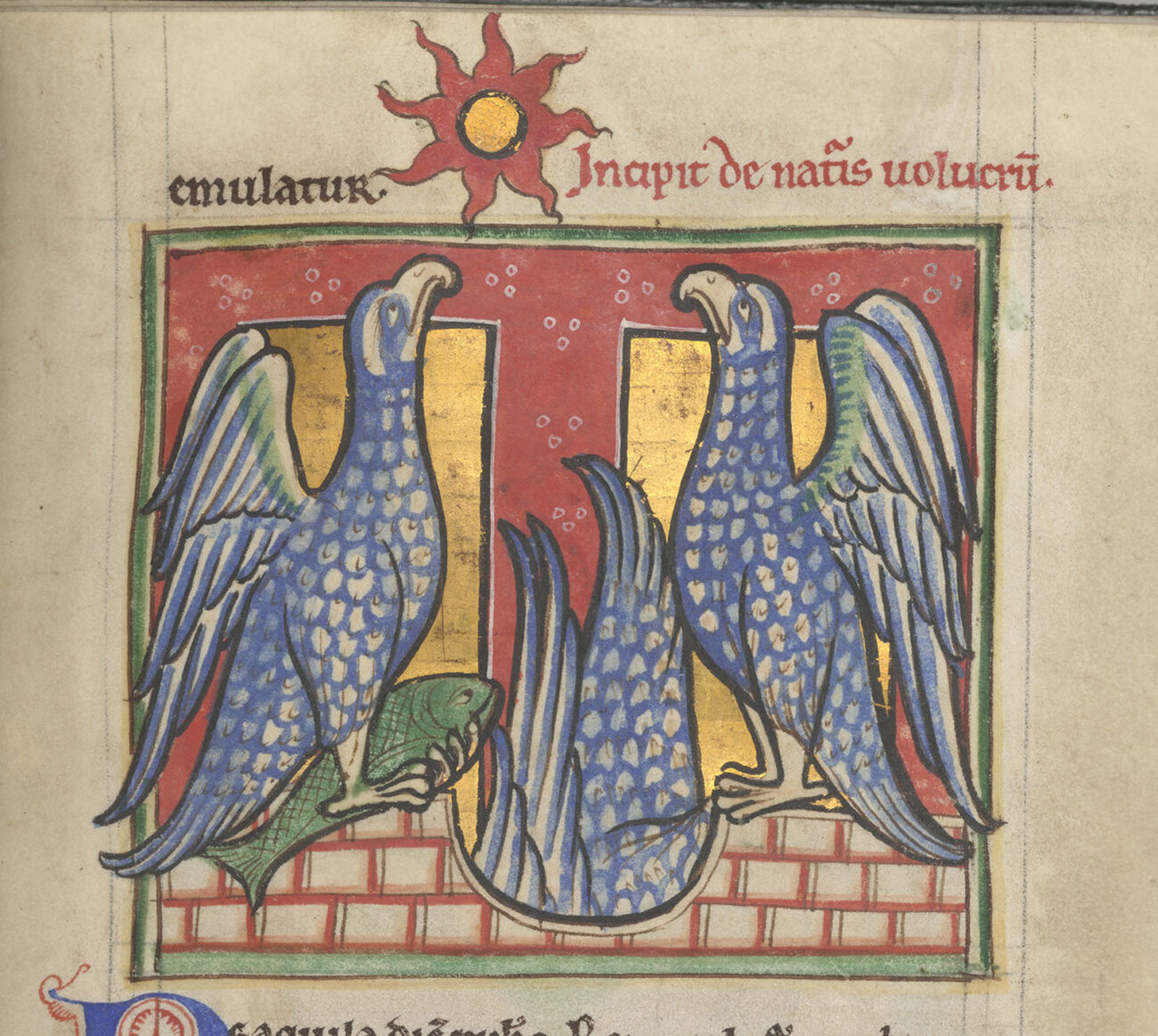

Birds

This opening shows a manuscript’s transition from land animals to birds. Just as the lion was known as the king of beasts, the eagle was supreme among birds. The eagle was described as losing its sight as it grows old, only to be rejuvenated by gazing at the sun.

Serpents

Serpents often came next. This page depicts the dragon, king of serpents, with a fire-breathing specimen stretching diagonally across the page. The section of the text that describes the power of the dragon’s tail is visually interrupted by the tail itself, demonstrating the formidable nature of the beast as well as the meaningful ways in which text and image interacted in the bestiary.

Sea creatures

![Whale (detail) from a bestiary, about 1270, unknown illuminator, made possibly in Thérouanne, France, tempera colors, gold leaf, and ink on parchment, 7 1/2 × 5 5/8 inches (The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig XV 3 [83.MR.173], fol. 89v. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program)](https://smarthistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/6.-lri_gm_005476D1V1_1600-1300x1484-1.jpg)

The final section of the bestiary usually dealt with sea creatures. Here an enormous whale plunges into the depths, dragging two hapless fishermen with it. The text describes this beast as so massive that sailors confuse its back for an island. When they make camp and light a fire, the whale feels the heat and dives down, drowning its surprised visitors. This story is presented as a warning against the deceptions of the devil. The artist skillfully evokes the sense of horror felt by the sailors at the exact moment they discover their tragic mistake.

Beasts beyond the bestiary

The bestiary’s stories and images were so popular that medieval artists readily adapted them for other kinds of manuscripts, as well as for various other types of art.

Because many bestiary animals communicated complex religious messages, they often appeared in liturgical and devotional contexts where worshippers could easily link them to Christian ideology. But the well-known characteristics associated with numerous beasts—the unicorn, the elephant, and the fox, among others—also made them an ideal match for secular artworks made for the elite world of the court. Over time, the memorable creatures that were central to the bestiary tradition pervaded the visual vocabulary of the medieval world, becoming some of the most common symbols in art of the Middle Ages.

For example, the elephant appears as a symbol of strength in artworks of many media, including this metal candlestick. The howdah, a structure used to carry soldiers on the back of an elephant, was a symbol of the animal’s might. This candlestick is ingeniously shaped so that the pricket (spike) for the candle stands on the upper tower of the howdah, while the crenellated edge of the tray is designed to catch the wax.

The fox was described in the bestiary as a trickster that would roll over on its back and pretend to be dead, luring unsuspecting birds into its midst. The fox would then snap its jaws shut on the birds that had fallen for the ruse. Tales of the fox spread far and wide in the Middle Ages, even informing popular literature of the period.

A series of medieval moral stories with animal characters revolves around a trickster fox named Reynard. A lion called Noble, the literal king of beasts in the tale, often tries to hold Reynard accountable for his ploys. The tales of Reynard became so popular in France that the common word for fox in modern French does not derive from the Latin term vulpus, but is actually the word reynard.

The animals in this millefleurs (thousand-flowers) tapestry seem at first to be scattered randomly for purely decorative effect. Yet the stag, the unicorn, and the lion were all associated with Christ in the stories of the bestiary. Their careful placement in this tapestry, forming a vertical row of three within the triangle created by the rosebushes, strengthens the group’s resonance with the Christian concept of the Trinity — the three manifestations of God as the Father, the Son (Christ), and the Holy Spirit.

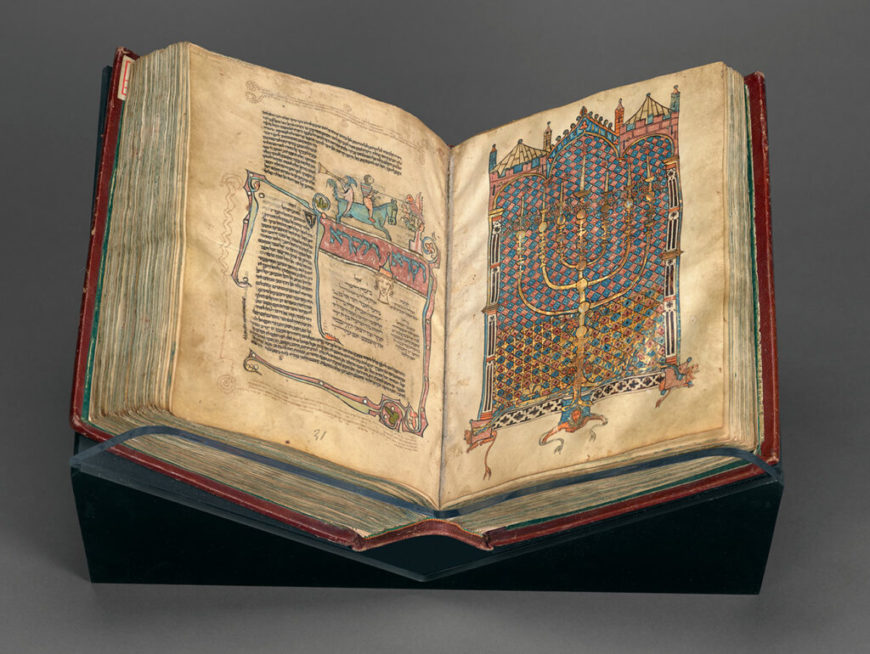

The use of animals as allegories for human virtues and vices was not limited to European Christian art, but was a widespread phenomenon that transcended geography and religion. In this Hebrew Bible, the bestiary image of a father lion breathing life into his dead cub accompanies the passage in Genesis in which God commands Abraham to sacrifice his son Isaac. According to some rabbinic commentaries, Abraham actually killed Isaac, but Isaac was miraculously brought back to life. For Christians, the tale of the lion was seen as a reference to Christ’s death and resurrection, but here a Jewish audience might have viewed it within the framework of the story of Abraham and the revival of Isaac.

The bestiary and natural history

The medieval bestiary was never intended as a scientific work, but much of its lore was eventually incorporated into the nascent field of natural history. The period of the bestiary’s greatest popularity, from about 1100 to 1300, corresponded with a movement to create encyclopedias that would gather all knowledge. Many of these encyclopedias included a section devoted to animals, which relied heavily on the bestiary but often stripped away the Christian symbolism.

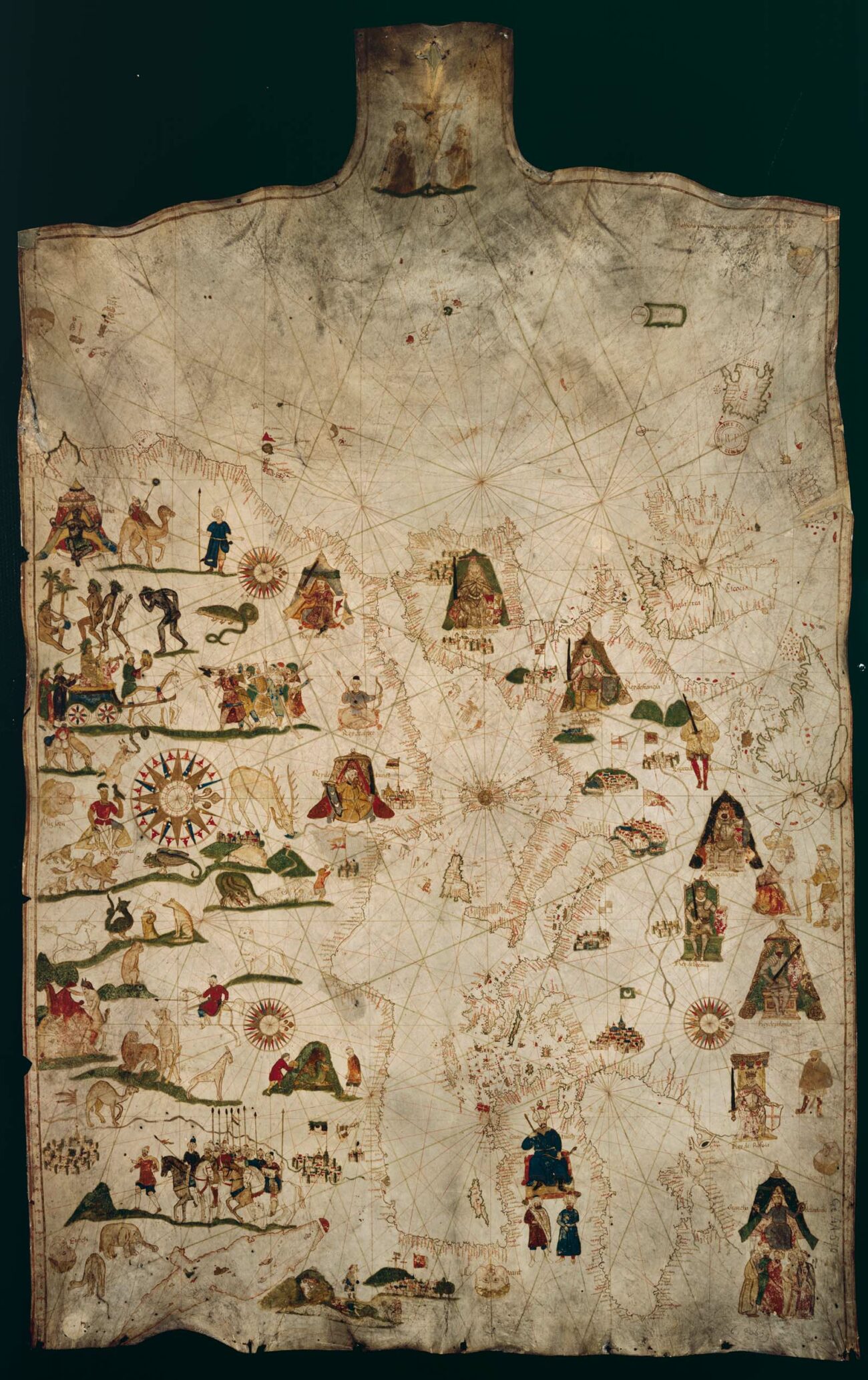

At this same time, the European conception of the world was being broadened by a growth in trade and travel that increasingly linked Western Europe with other parts of the globe. In the developing field of cartography, maps and navigational charts represented the world’s creatures in their respective regions.

The griffin

The griffin is one of only a few animals to be illustrated in what is often identified as the first medieval encyclopedia, known as the Book of Flowers (see image at the top of this article). A mythical hybrid between a lion and an eagle, the griffin was believed to carry away full-grown men to feed its young; this legend is found in ancient texts as well as the medieval bestiary. The griffin’s featured presence in this book—along with its alleged remains in church treasuries across Europe—attests to its central place in the medieval imagination.

The griffin’s presence in such texts lent credibility to supposed griffin claws (usually ibex horns), which were highly prized as physical specimens well into the late sixteenth century. An inscription on the mount identifies this example as belonging to the shrine of Saint Cuthbert in Durham, which recorded two such claws in addition to several “griffin eggs” (probably ostrich eggs) in an inventory from 1383.

Medieval maps were often oriented with south on the left and north on the right. In this chart made for navigation at sea, many animals occupy the left-hand portion representing Africa. Creatures such as the unicorn, camel, and lion reflect the medieval perception of far-flung lands as exotic and perhaps dangerous.

The legacy of the bestiary

In the visual arts, the rich legacy of the bestiary lasted far beyond the Middle Ages. Twentieth-century artists revived the pairing of animal imagery and text, calling their creations “bestiaries” after the medieval example. Today the term often refers to any collection of descriptions of animals, whether in words or images, but not necessarily with associated allegories or Christian connotations.

Writers and artists revived the genre of the illustrated bestiary in the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries, when a variety of new poetic and prose texts of animal lore appeared with illustrations created by established artists and printmakers.

A notable example of the early twentieth-century bestiary was the French poet Guillaume Apollinaire’s foray into illustrated fine art books. Apollinaire’s text was eventually published with thirty wood engravings by Raoul Dufy. Dufy’s wood engravings of animals are bold and forceful, with large swaths of deeply imprinted black ink contrasting with the milky white paper, imitating the block-book style of the early printed images of the fifteenth century.

The human relationship to the animal world is today a subject of intense interest and even debate, with the animals themselves caught in between as questions of conservation and environmental change are addressed by scientists, politicians, and activists. Contemporary artists, too, respond to these questions, participating in a long tradition of depicting animals in art that offers a commentary on the role of animals in our world.

The taxidermy hybrid creatures created by contemporary sculptor Kate Clark speak to the ubiquitous tendency of humans to see themselves in animals. Clark often “upcycles” hides that taxidermists or hunters don’t want. This work, entitled Licking the Plate, crystallizes this impulse, combining as it does an animal body with a human face that seems uncannily animate, reaching out across space and compelling the viewer to engage with the creature directly. As the medieval bestiary used animals to teach moral lessons, the fusion of human and animal in Clark’s work invites viewers to examine their natural instincts, the animal within, and the characteristics that unite disparate animal kingdoms.

This essay first appeared in the iris (CC BY 4.0).

Additional resources:

Morrison, Elizabeth, and Larisa Grollemond. Book of Beasts : The Bestiary in the Medieval World. Los Angeles: Published by the J. Paul Getty Museum, 2019.

The medieval calendar

Video \(\PageIndex{1}\): Video from the J. Paul Getty Museum

Chivalry in the Middle Ages

Video \(\PageIndex{2}\): Video by the J. Paul Getty Museum

A Global Middle Ages through the Pages of Decorated Books

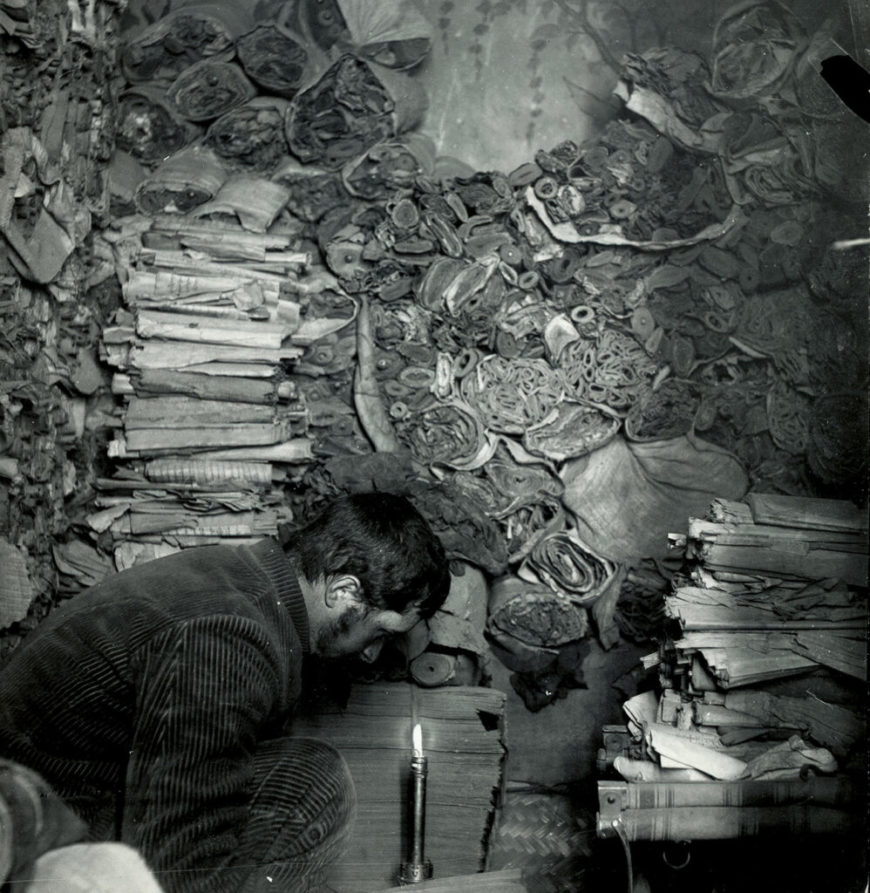

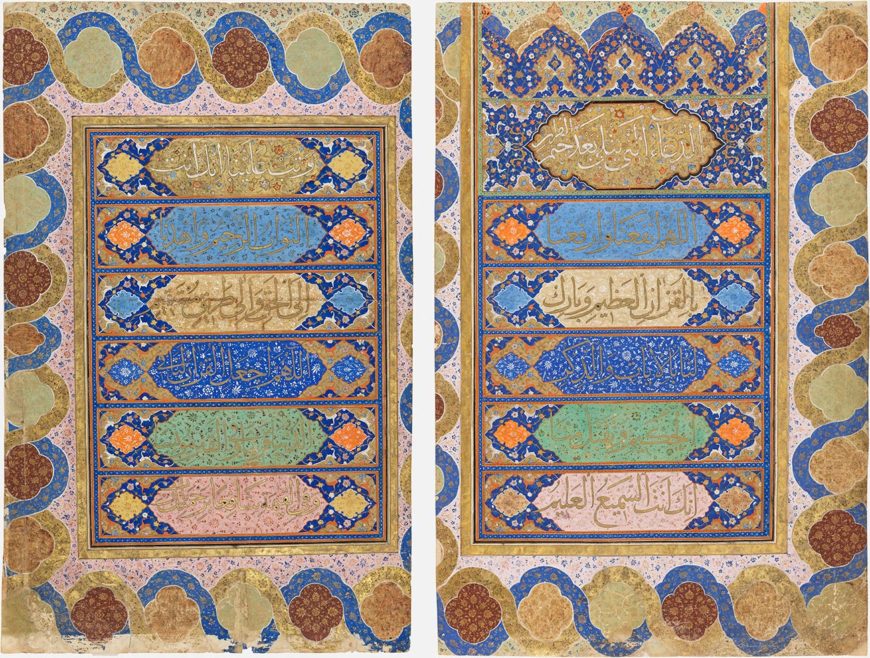

Manuscripts and printed books—like today’s museums, archives, and libraries—provide glimpses into how people have perceived the Earth, its many cultures, and everyone’s place in it. Toward a Global Middle Ages: Encountering the World through Illuminated Manuscripts, a new book from Getty Publications, invites you to explore this theme, presenting a range of book types from premodern Africa, Europe, Asia, the Americas, and Austronesia.

The production of books is a collaborative undertaking. In the premodern period, this process could involve the makers of writing surfaces, binding supports, scribes, procurers and creators of pigment, merchants, artists, patrons, and eventually the readers, viewers, or listeners. Toward a Global Middle Ages includes essays by twenty-six authors who are specialists of the art of the book.

Whose Middle Ages?

What do we mean by a global Middle Ages (or medieval period)? Writing about the Middle Ages has traditionally centered on the Jewish, Christian, and Muslim communities in Europe, Western Asia, and the greater Mediterranean between the years 500 and 1500. The term “Middle Ages” was used in the nineteenth century to describe a medium aevum, a middle age between the Roman Empire and the Renaissance.

For decades, scholars have challenged this Eurocentric view of the past, turning attention to a global Middle Ages that includes Africa, Asia, the Americas, and Austronesia. Some of these scholars seek to uncover networks, pathways, routes, or links between people and places. In doing so, an aim has been to reveal the lives of those who have been silenced by history or tradition: women, enslaved individuals, Indigenous peoples, queer or disabled groups. Others take a comparative approach, examining similar phenomena in different places at the same time or over time. Toward a Global Middle Ages expands upon these perspectives.

There are also discussions about the meaning of “global” at a local level, and whether it is possible to speak of early globalities prior to the sustained transatlantic contacts between Europe, the Americas, and Africa in the late fifteenth century (it should be acknowledged that the latter view still largely centers on Europe—as indicated below and in the volume, peoples of northeastern China and Siberia had contacts with First Nation peoples, including those who inhabited the Aleutian Islands).

Some scholars select a hemispheric focus—referring to a hemispheric Middle Ages—that concentrates on Africa, Europe, and Asia on the one hand, and the Americas on the other. With this approach, we can still find connections through comparisons if we look to astronomy or astrology, for example, as I discuss in Toward a Global Middle Ages and have outlined briefly before; we might also consider global climate change (evidenced through ice cores and testimony from manuscripts or oral traditions) and the spread of diseases or the relationship between botany and linguistic development of words for popular trade goods, such as sweet potato or tea. Whichever methodology seems most applicable to the scope of a given study, one recommendation is to continually resist Eurocentrism and to cross boundaries—of periodization, discipline or specialization, historical or present-day geography, language (of documents and of academic training), and so forth.

It takes time to redirect the writing of history. The authors of this book therefore describe what we do as working toward a global Middle Ages.

Paper, Parchment, and Palm Leaves

Books were key modes of cultural expression and exchange throughout the Middle Ages. Manuscript means “handwritten,” from the Latin words manus (“hand”) and scriptus (“written”). Lavish examples were often embellished with metallic leaf or paint that shimmered in the light, which gives us the term “illuminated.” Print technology allowed images and texts to be replicated, and some global traditions combined manuscript and print.

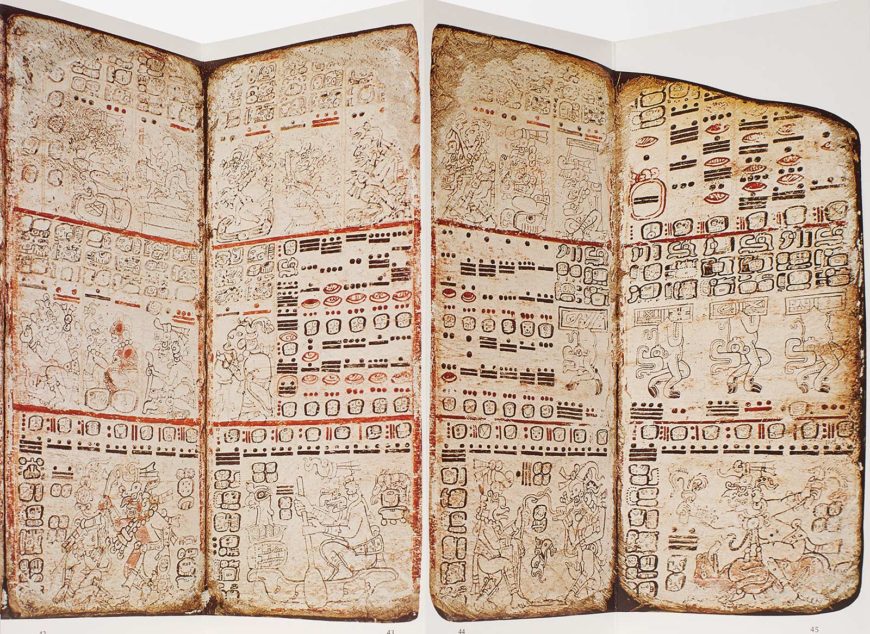

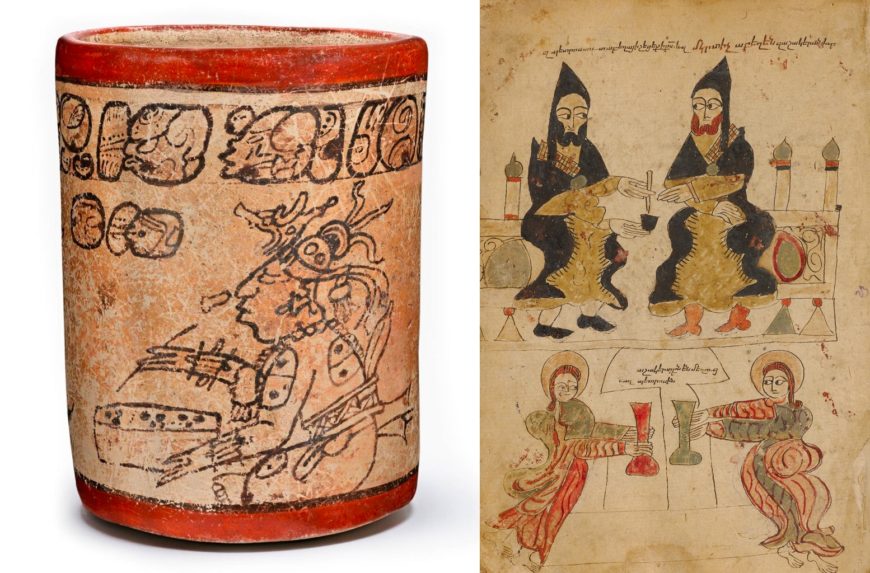

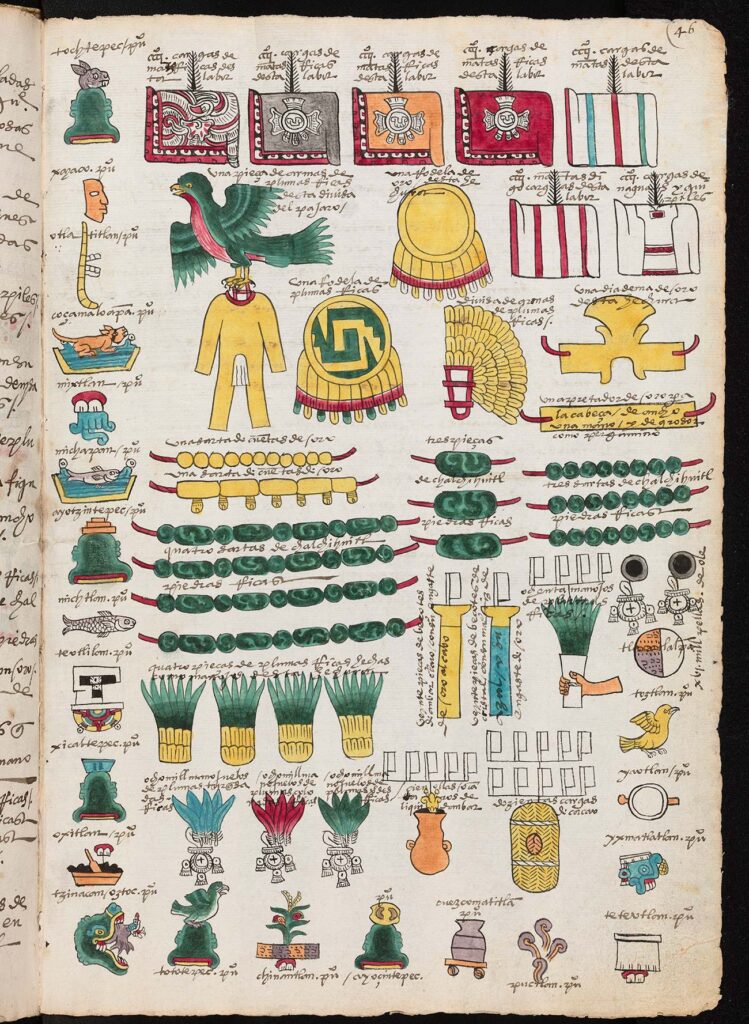

Across Afro-Eurasia, the Americas, and Austronesia during the medieval period, bookmakers used a variety of supports and structures, including paper, parchment, and palm leaves. Each of these could be gathered together in various ways: bound as a codex, rolled as a scroll, or folded as an album. In some instances, we have to look at other types of artworks for glimpses of book or writing traditions (as with the Maya, whose long history of codex creation was decimated by the Spanish conquest yet ceramic vessels provide evidence for early manuscript production in Mesoamerica). The examples shown in this post hint at the diversity of book types and formats.

Manuscripts and books operated alongside other forms of literacy and visual storytelling throughout the Middle Ages. These include glyphic and graphic examples—characters or symbols carved or painted onto a surface, such as stone, ceramic, or the body—as well as oral traditions and memory aids. Such varied objects shed light on the many ways in which the book, broadly defined, functioned in multiple contexts in the past, and on the relationship between the visual arts and language, storytelling, and the commemoration of the past.

A World Without a Center

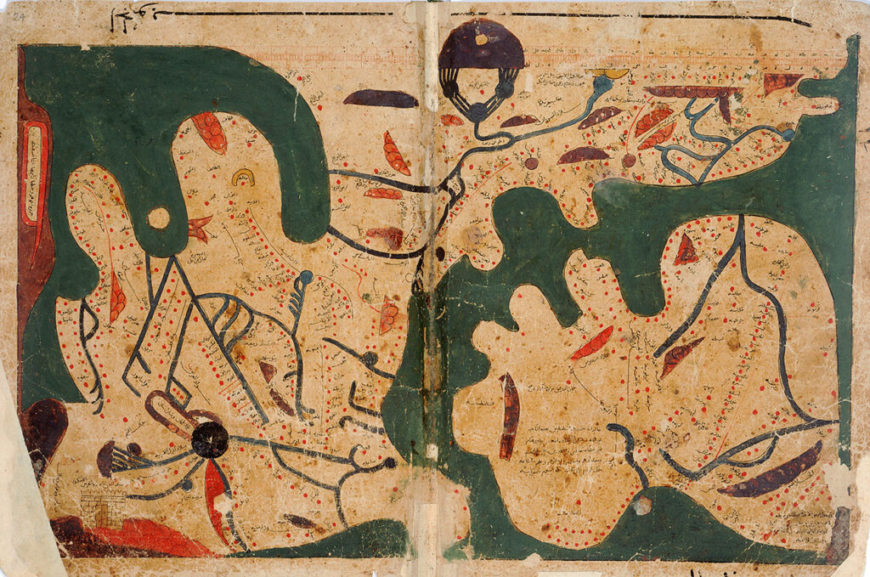

Maps are another focus of the new publication. Like manuscripts, maps present world views, including views of self and others; they also change frequently and are often political.

Fascinating parallels emerge when looking at maps across cultures. The 11th-century “Book of Curiosities” from Egypt, for example, describes legendary peoples and creatures that also appear in a 13th-century European compendium of Latin texts. The Ottoman admiral-mapmaker Piri Reis and the Korean scholar Kwon Kun created maps that include portions of the Americas (Brazil and the Aleutian Islands of present-day Alaska, respectively).

Mapping can also take many forms. On the Shoshone-Bannock Map Rock in Idaho, for example, Indigenous mapmakers charted astrological and geographic information onto the surface of rocks. The 1542 Codex Mendoza features a Nahua map of the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan and visualizes the tribute from the provinces as luxury items of jade and feathers.

Through these and many other examples of maps, manuscripts, and related book arts, Toward a Global Middle Ages demonstrates that geographic and cultural boundaries were and are porous, fluid, and permeable.

My co-authors and I hope this new book contributes to the vibrant conversations about a global Middle Ages, and to the role of manuscripts and visual culture in these conversations. I welcome comments and questions about the book and its themes, and particularly hope it can be of use to instructors and students—see the resource list below, prepared with research and classroom use in mind.

This essay first appeared on the iris (CC BY 4.0).

Additional resources

Download a resource list for Toward a Global Middle Ages, including the table of contents, related Getty online resources, and a list of manuscripts and books discussed in the book.

Toward a Global Middle Ages: Encountering the World through Illuminated Manuscripts, ed. Bryan C. Keene (Los Angeles: The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2019)

Catherine Holmes and Naomi Standen, “Introduction: Towards a Global Middle Ages,” Past & Present, vol. 238 (November 2018), pp. 1–44

Musical imagery in the Global Middle Ages

Infernal Noise

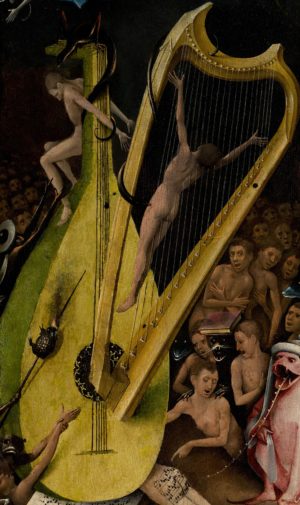

In the Hell panel of Hieronymus Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights triptych, an anthropomorphic, fully clothed hare blows a hunting horn, the hunted aping the hunter. A naked man, penetrated by a recorder, carries an oversized shawm (wind instrument) on his back, apparently suffering under its weight, his posture reminiscent of Jesus’ in images of Christ carrying the cross.

At left, a naked figure is bound to the neck of an elegant lute. Bizarre as these ghastly scenes may appear, they actually have a certain logic. In fact, they respond to a vast and surprisingly consistent body of global medieval musical images, examples of which we will explore below. If anything, the Boschian scene leverages the instrument’s usual associations with melodious, soothing music and puts an ironic twist on the sacred to visualize the profane.

David and his harp

In Bosch’s triptych, a finely crafted harp protrudes at an angle from the broken rosette of a lute. A slick, black, reptilian tail curls around the wooden frame of the harp, boring a hole through its top. The gargantuan string instrument becomes an instrument of torture, its delicate, taut strings running clear through the body of a naked figure—one of the damned. The detail sends a moralizing message—condemning some forms of instrumental music as sinful.

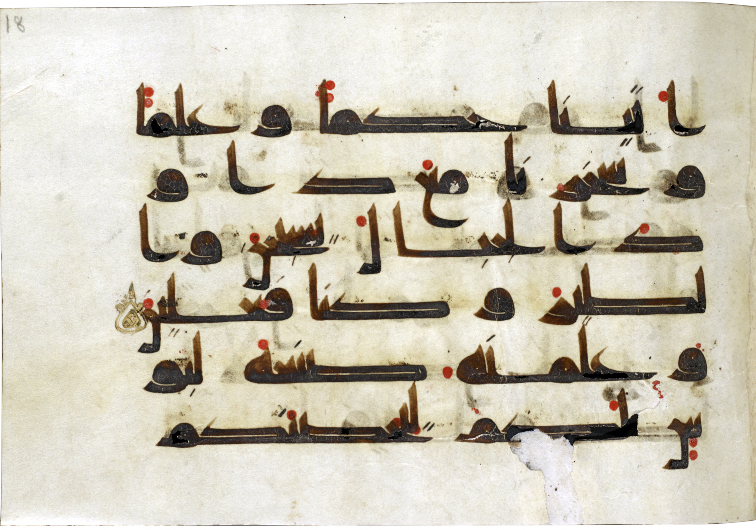

And yet, more innocuous visual representations of harpists also abound in global medieval art, demonstrating that string instruments frequently referred to praising God rather than sinful worldly pleasure. A similar harp appears in a Dutch vernacular Book of Hours produced in Utrecht a few decades before Bosch painted his triptych. In the lower margin of one page, the biblical King David strums a contemporary harp. In medieval Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, the psalms were attributed to David, and multiple sacred texts associated with the Abrahamic faiths attested to David’s musicality. For example, the Islamic Qur’an portrays David as a prophet whose songs praising God reverberated throughout the landscape, amplified by birdsong:

We made the mountains and the birds celebrate Our praises with David. [1]

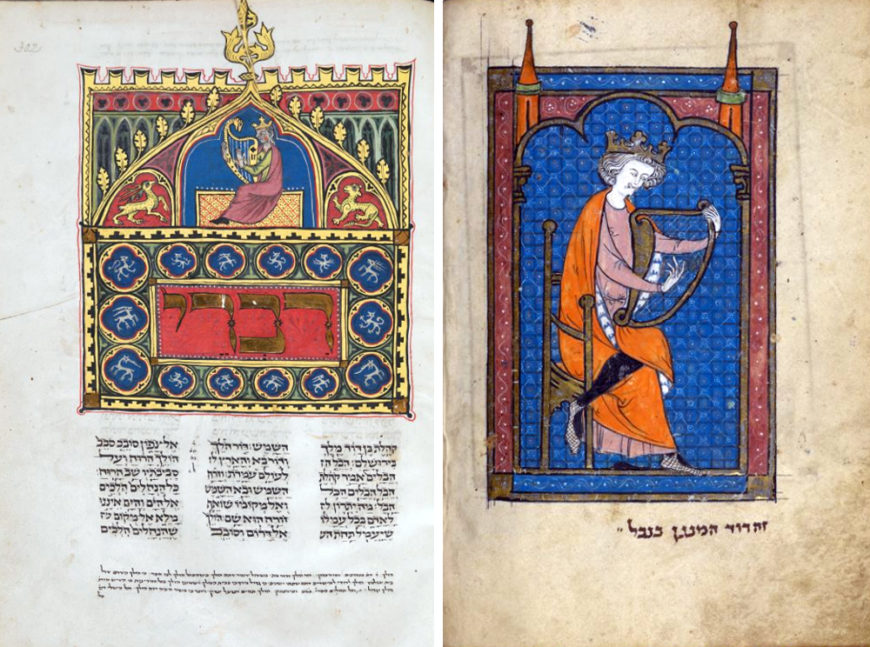

In one early Qur’an manuscript, this particular verse (aya) takes up most of the parchment page. The text is the focal point. Unlike the Book of Hours from Utrecht, there is no figural imagery in the margins. It is only the Qur’anic verse itself, written calligraphically in Kufic script with black letters and red vowel marks, that would bring the musician David to the reader’s mind. Medieval Jewish and Christian manuscripts likewise address David’s musical prowess through the beautifully written word. Many sumptuous sacred books also contain musical imagery to amplify the message. David is so often shown playing the harp in medieval manuscripts, stained glass, and sculpture that it is among the most stable and readily identifiable examples of medieval musical iconography.

Two roughly contemporaneous illuminated Hebrew scriptural manuscripts—one created in what is now Germany, and the other produced in present-day France—contain depictions of King David playing the harp. In both cases, the biblical ruler is shown crowned and enthroned, his body positioned within a micro-architectural frame. The musical iconography appears in a different context in each manuscript. The half-page illumination featuring a combination of figural, zoomorphic, textual, and architectonic elements acts as the heading of the book of Ecclesiastes, whereas the full-page illumination, with a descriptive label written in Hebrew in the lower margin, is one in a series of full-page illustrations sandwiched between the book of Deuteronomy and the Haftarot.

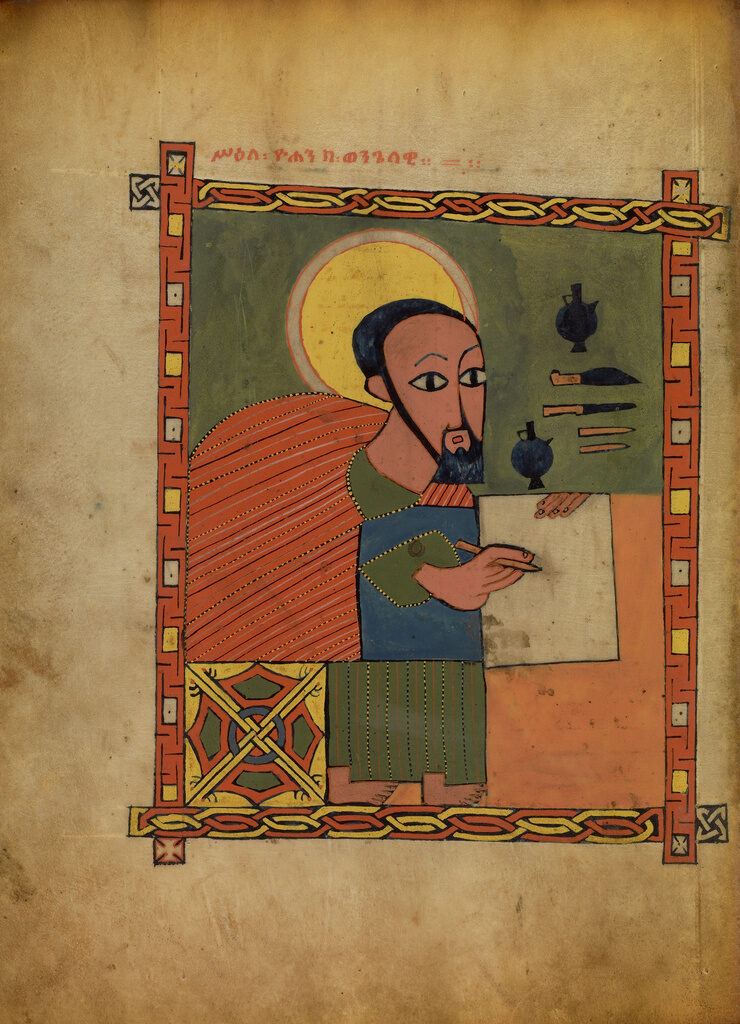

David is shown playing a contemporary harp in the examples we have seen thus far. Similarly, in a 15th-century Ethiopic Psalter, David raises his left hand to play a contemporary begena, a ten-stringed box lyre.

Occasionally, however, medieval artists showed David playing a historical or fanciful instrument, presumably as a means of historicizing the biblical figure. For example, the illuminator of the so-called Paris Psalter, a 10th-century Byzantine Psalter made in Constantinople, apparently meant to depict the historical instrument identified in the Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible (the Septuagint) as a kithara (κιθάρᾳ). A classicizing, full-page illumination shows David extending his right index finger to pluck a string of a kind of box lyre.

Soothing Melodies

But of all the instruments mentioned in the Bible, why was David most closely associated with the harp? One Bible story explicitly draws a connection between the two:

So whenever the evil spirit from the Lord was upon Saul, David took his harp, and played with his hand, and Saul was refreshed, and was better, for the evil spirit departed from him.[2]

This passage demonstrates the powerful effects of David’s harp music: it wards off evil and soothes the king. A detailed version of the scene appears on a page of The Morgan Picture Bible. At left, David trains his gaze on the strings of his harp as he plays, the curve of his body mirroring the frame of his instrument. At right, the palliative effects of the music are evident. A winged creature, the physical manifestation of the evil spirit that had been tormenting King Saul, flees the scene. The king is left in a peaceful slumber, with his right hand gently cradling his head as he nods off.

Moving Melodies

It is not only in medieval sacred art that harp music elicits physical, emotional, and supernatural responses. Painted on the inside of a ceramic bowl made in Kashan (in modern-day Iran), a hunter and a harpist ride together on the back of a racing camel. The hunter holds his bow with his right hand, and he wraps the fingers of his left hand around the string of his bow, withdrawing his arm to release an arrow. Behind him, the harpist grasps the frame of her instrument with her right hand, curling the fingers of her left hand to pluck the harp strings. The scene comes from the Book of Kings (Shahnama), the 10th-century Persian poet Firdausi’s epic poem, and thus the two figures on camelback represent the Sasanian prince Bahram Gur and the harpist Azada. The unmistakable visual parallel between Bahram Gur’s weapon and Azada’s musical instrument is made explicit in the text of another version of the story, written by the 12th-century poet Nizami. In it, the harpist is named Fitna, not Azada; Bahram Gur hunts onager rather than gazelle; and the effects of the harpist’s mellifluous music on human beings and animals alike are more fully articulated:

She played and sang with elegance,

and was quick-footed at the dance.

When to the lute she joined her song,

the birds from air to ground would throng.

Most often, at the hunt or feast,

the king her sweet songs would request.

The harp her weapon, the king’s the bow:

she struck up tunes, he laid game low. [3]

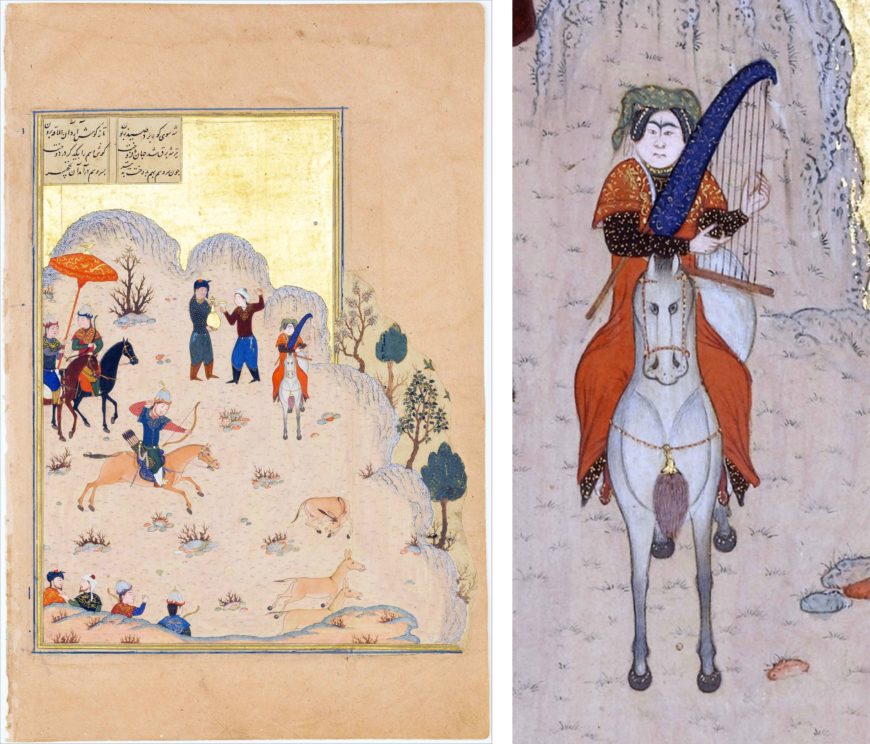

Illustrated copies of Nizami’s poem frequently juxtapose Bahram Gur’s bow and Fitna’s harp, as on a page of a magnificent 15th-century manuscript painted in Herat, in what is now Afghanistan. In this visual interpretation, Fitna is mounted on a horse, playing a harp whose blue sound box with gold detailing is as intricately embellished as the fine textiles she wears. Appearing in the context of an idealized portrayal of the Persian ruler, the harp evokes the courtly culture of a distant and heroic Sasanian past.

The courtly setting for harp music is common across temporal, geographic, linguistic, and cultural boundaries. For example, Chinese funerary figurines known as mingqi sometimes took the form of courtly musicians, as in a Tang example of a harp (konghou) player—one of a group of seated female musicians meant to go on entertaining the deceased in the afterlife. A poem written by Li He a century after the figurines were created opens by identifying the provinces where the wood (for the sound box) and silk (for the strings) were sourced to build the titular character’s 23-stringed harp. In the poem, Li Ping’s harp playing triggers emotional, physical, and cosmic responses:

Silk from Wu, paulownia from Shu,

Strummed in high autumn,

In the white sky the frozen clouds

Falling, not floating.

Ladies of the River weeping among bamboos,

The White Girl mournful

As Li Ping plays his harp

In the center of the Kingdom.

Jade from Mount Kun is shattered,

Phoenixes shriek,

Lotuses are weeping dew,

Fragrant orchids smile.

Before the twelve gates of the city

The cold light melts,

The twenty-three strings can move

The Purple Emperor. [4]

Studying musical iconography

Texts and images produced throughout the medieval world reveal that, in the hands of an adept player, harp music could elicit powerful responses. It could enchant courtly listeners, ward off evil, or even reshape the material world. Seen in this light, the harp in The Garden of Earthly Delights triptych may have been an indictment of anyone who chose to wield this power to nefarious ends.

As this brief overview has shown, studying musical iconography requires an eye for detail; an appreciation for the power of music to move listeners; open-mindedness about the ways images of sound and music conveyed meaning, often in tandem with religious or poetic texts; and, in light of the fact that instruments are played with the human body, a healthy sense of humor.

The open-access database Musiconis, newly available in English, makes a vast repository of medieval musical imagery available to scholars, students, and the general public. Readers are invited to explore the objects in Musiconis at their leisure to make new connections and draw their own conclusions about the role of music in global medieval art.

Notes:

[1] Sura 21 (The Prophets [al-Anbiya’]), Aya 79, Qur’an, trans. M. A. S. Abdel Haleem (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008), 206.

[2] 1 Samuel 16:23, Douay-Rheims Bible.

[3] Nizami, Haft Paykar: A Medieval Persian Romance, trans. Julie Scott Meisami (Hackett, 2015), 25, pp. 16-19.

[4] Li He, “Song: Li Ping at the Vertical Harp [Li Ping Konghou Yin],” in The Collected Poems of Li He, trans. J. D. Frodsham (New York Review of Books, 2016), p. 74.

Additional resources

Search the Musiconis medieval musical iconography database (in English and French)

Nasrin Askari, The Medieval Reception of the Shahnama as a Mirror for Princes (Leiden; Boston: Brill, 2016).

Sarah E. Bond, “British Exhibitions of Ethiopian Manuscripts Prompt Questions About Repatriation,” Hyperallergic (blog), June 18, 2018.

Susan Boynton and Diane Reilly, eds., Resounding Images: Medieval Intersections of Art, Music, and Sound (Turnhout: Brepols, 2015).

Michael Camille, Image on the Edge: The Margins of Medieval Art (London: Reaktion Books; Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2019 [1992]).

Heather Colburn Clydesdale, “The Vibrant Role of Mingqi in Early Chinese Burials,” Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History (April 2009).

Marc Michael Epstein, “The Elephant and the Law: The Medieval Jewish Minority Adapts a Christian Motif,” The Art Bulletin vol. 76, no. 3 (September 1994), pp. 464-478.

David R. M. Irving, “Psalms, Islam, and Music: Dialogues and Divergence about David in Christian-Muslim Encounters of the Seventeenth Century,” Yale Journal of Music & Religion vol. 2, no. 1 (2016), pp. 53-78.

Bo Lawergren, “Harp,” Encyclopedia Iranica, December 15, 2003.

Bo Lawergren, “Harps on the Ancient Silk Road,” in Conservation of Ancient Sites on the Silk Road: Proceedings of the Second International Conference on the Conservation of Grotto Sites, ed. Neville Agnew (Los Angeles: The Getty Conservation Institute, 2010), pp. 117-123.

Alexandra Schwartz, “Click Here to Visit Hell: An Interactive ‘Garden of Earthly Delights,’” The New Yorker, April 12, 2016.

Stéphanie Weisser, “The Ethiopian Lyre bagana: an instrument for emotion,” Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Music Perception and Cognition (2006), pp. 376-382.