4.6: Southern Africa

- Page ID

- 67984

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Southern Africa

Southern Africa is home to William Kentridge, Great Zimbabwe, and the Apollo 11 Stones.

28,000 B.C.E. - present

About Southern Africa

by SMARTHISTORY

Southern Africa includes Angola, Botswana, Lesotho, Madagascar, Malawi, Mauritius, Mozambique, Namibia, South Africa, Swaziland, Zambia and Zimbabwe.

The art of Namibia

In the mountains of Southern Namibia, researchers uncovered stunning rock art from nearly 30,000 years ago.

28,000 - 26,000 B.C.E.

Origins of rock art in Africa

Rock art and the origins of art in Africa

The oldest scientifically-dated figurative rock art in Africa dates from around 26,000-28,000 years ago and is found in Namibia.

Between 1969 and 1972, German archaeologist, W.E. Wendt, researching in an area known locally as “Goachanas,” unearthed several painted slabs in a cave he named Apollo 11, after NASA’s successful moon landing mission.

Seven painted stone slabs of brown-grey quartzite, depicting a variety of animals painted in charcoal, ochre and white, were located in a Middle Stone Age deposit (100,000–60,000 years ago). These images are not easily identifiable to species level, but have been interpreted variously as felines and/or bovids; one in particular has been observed to be either a zebra, giraffe or ostrich, demonstrating the ambiguous nature of the depictions.

Art and our modern mind

While the Apollo 11 plaques may be the oldest discovered representational art in Africa, this is not the beginning of the story of art. It is now well-established, through genetic and fossil evidence, that anatomically modern humans (Homo sapiens sapiens) developed in Africa more than 100,000 years ago; of these, a small group left the Continent around 60,000-80,000 years ago and spread throughout the rest of the world.

Recently discovered examples of patterned stone, ochre and ostrich eggshell, as well as evidence of personal ornamentation emerging from Middle Stone Age Africa, have demonstrated that “art” is not only a much older phenomenon than previously thought, but that it has its roots in the African continent. Africa is where we share a common humanity.

The first examples of what we might term “art” in Africa, dating from between 100,000–60,000 years ago, emerge in two very distinct forms: personal adornment in the form of perforated seashells suspended on twine, and incised and engraved stone, ochre and ostrich eggshell. Despite some sites being 8,000km and 40,000 years apart, an intriguing feature of the earliest art is that these first forays appear remarkably similar. It is worth noting here that the term “art” in this context is highly problematic, in that we cannot assume that humans living 100,000 years ago, or even 10,000 years ago, had a concept of art in the same way that we do, particularly in the modern Western sense. However, it remains a useful umbrella term for our purposes here.

Pattern and design

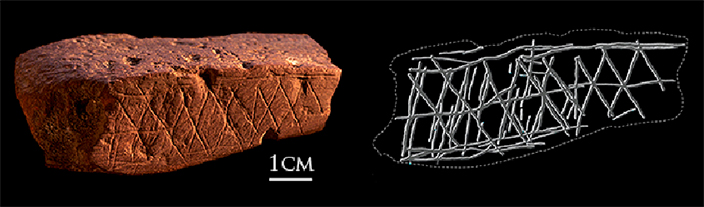

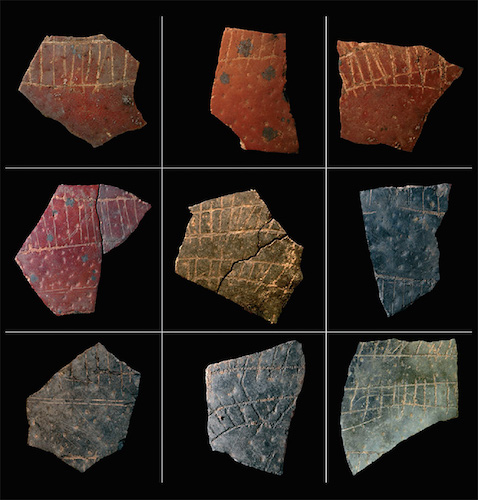

The practice of engraving or incising, which emerges around 12,000 years ago in Saharan rock art, has its antecedents much earlier, up to 100,000 years ago. Incised and engraved stone, bone, ochre and ostrich eggshell have been found at sites in southern Africa. These marked objects share features in the expression of design, exhibiting patterns that have been classified as cross-hatching.

One of the most iconic and well-publicised sites that have yielded cross-hatch incised patterning on ochre is Blombos Cave, on the southern Cape shore of South Africa. Of the more than 8,500 fragments of ochre deriving from the MSA (Middle Stone Age) levels, 15 fragments show evidence of engraving. Two of these, dated to 77,000 years ago, have received the most attention for the design of cross-hatch pattern.

For many archaeologists, the incised pieces of ochre at Blombos are the most complex and best-formed evidence for early abstract representations, and are unequivocal evidence for symbolic thought and language. The debate about when we became a symbolic species and acquired fully syntactical language – what archaeologists term ‘modern human behaviour’ – is both complex and contested. It has been proposed that these cross-hatch patterns are clear evidence of thinking symbolically, because the motifs are not representational and as such are culturally constructed and arbitrary. Moreover, in order for the meaning of this motif to be conveyed to others, language is a prerequisite.

The Blombos engravings are not isolated occurrences, since the presence of such designs occur at more than half a dozen other sites in South Africa, suggesting that this pattern is indeed important in some way, and not the result of idiosyncratic behaviour. It is worth noting, however, that for some scholars, the premise that the pattern is symbolic is not so certain. The patterns may indeed have a meaning, but it is how that meaning is associated, either by resemblance (iconic) or correlation (indexical), that is important for our understanding of human cognition.

Personal ornamentation and engraved designs are the earliest evidence of art in Africa, and are inextricably tied up with the development of human cognition. For tens of thousands of years, there has been not only a capacity for, but a motivation to adorn and to inscribe, to make visual that which is important. The interesting and pertinent issue in the context of this project is that the rock art we are cataloguing, describing and researching comes from a tradition that goes far back into African prehistory. The techniques and subject matter resonate over the millennia.

Additional resources:

British Museum African Rock Art Image Project

© Trustees of the British Museum

Apollo 11 Cave Stones

by NATHALIE HAGER

A significant discovery

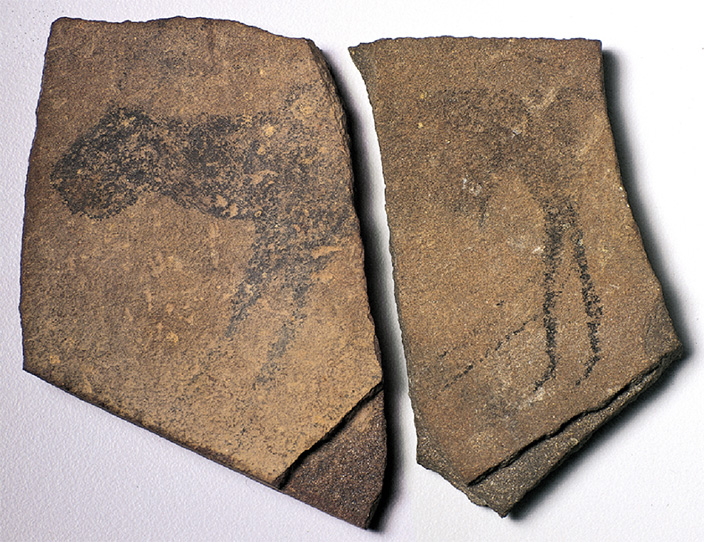

Approximately 25,000 years ago, in a rock shelter in the Huns Mountains of Namibia on the southwest coast of Africa (today part of the Ai-Ais Richtersveld Transfrontier Park), an animal was drawn in charcoal on a hand-sized slab of stone. The stone was left behind, over time becoming buried on the floor of the cave by layers of sediment and debris until 1969 when a team led by German archaeologist W.E. Wendt excavated the rock shelter and found the first fragment (above, left). Wendt named the cave “Apollo 11” upon hearing on his shortwave radio of NASA’s successful space mission to the moon. It was more than three years later however, after a subsequent excavation, when Wendt discovered the matching fragment (above, right), that archaeologists and art historians began to understand the significance of the find.

Indirect dating techniques

In total seven stone fragments of brown-grey quartzite, some of them depicting traces of animal figures drawn in charcoal, ocher, and white, were found buried in a concentrated area of the cave floor less than two meters square. While it is not possible to learn the actual date of the fragments, it is possible to estimate when the rocks were buried by radiocarbon dating the archaeological layer in which they were found. Archaeologists estimate that the cave stones were buried between 25,500 and 25,300 years ago during the Middle Stone Age period in southern Africa making them, at the time of their discovery, the oldest dated art known on the African continent and among the earliest evidence of human artistic expression worldwide. What was the Middle Stone Age?

While more recent discoveries of much older human artistic endeavors have corrected our understanding (consider the 2008 discovery of a 100,000-year-old paint workshop in the Blombos Cave on the southern coast of Africa), the stones remain the oldest examples of figurative art from the African continent. Their discovery contributes to our conception of early humanity’s creative attempts, before the invention of formal writing, to express their thoughts about the world around them.

The origins of art?

Genetic and fossil evidence tells us that Homo sapiens (anatomically modern humans who evolved from an earlier species of hominids) developed on the continent of Africa more than 100,000 years ago and spread throughout the world. But what we do not know—what we have only been able to assume—is that art too began in Africa. Is Africa, where humanity originated, home to the world’s oldest art? If so, can we say that art began in Africa?

100,000 years of human occupation

The Apollo 11 rock shelter overlooks a dry gorge, sitting twenty meters above what was once a river that ran along the valley floor. The cave entrance is wide, about twenty-eight meters across, and the cave itself is deep: eleven meters from front to back. While today a person can stand upright only in the front section of the cave, during the Middle Stone Age, as well as in the periods before and after, the rock shelter was an active site of ongoing human settlement.

Inside the cave, above and below the layer where the Apollo 11 cave stones were found, archaeologists unearthed a sequence of cultural layers representing over 100,000 years of human occupation. In these layers stone artifacts, typical of the Middle Stone Age period—such as blades, pointed flakes, and scraper—were found in raw materials not native to the region, signaling stone tool technology transported over long distances. Among the remnants of hearths, ostrich eggshell fragments bearing traces of red color were also found—either remnants of ornamental painting or evidence that the eggshells were used as containers for pigment.

On the cave walls, belonging to the Later Stone Age period, rock paintings were discovered depicting white and red zigzags, two handprints, three geometric images, and traces of color. And on the banks of the riverbed just upstream from the cave, engravings of a variety of animals, some with zigzag lines leading upwards, were found and dated to less than 2000 years ago.

The Apollo 11 Cave Stones

But the most well-known of the rock shelter’s finds, and the most enigmatic, remain the Apollo 11 cave stones (image above). On the cleavage face of what was once a complete slab, an unidentified animal form was drawn resembling a feline in appearance but with human hind legs that were probably added later. Barely visible on the head of the animal are two slightly-curved horns likely belonging to an Oryx, a large grazing antelope; on the animal’s underbelly, possibly the sexual organ of a bovid. What is a bovid?

Perhaps we have some kind of supernatural creature—a therianthrope, part human and part animal? If so, this may suggest a complex system of shamanistic belief. Taken together with the later rock paintings and the engravings, Apollo 11 becomes more than just a cave offering shelter from the elements. It becomes a site of ritual significance used by many over thousands of years.

The global origins of art

In the Middle Stone Age period in southern Africa prehistoric man was a hunter-gatherer, moving from place to place in search of food and shelter. But this modern human also drew an animal form with charcoal—a form as much imagined as it was observed. This is what makes the Apollo 11 cave stones find so interesting: the stones offer evidence that Homo sapiens in the Middle Stone Age—us, some 25,000 years ago—were not only anatomically modern, but behaviorally modern as well. That is to say, these early humans possessed the new and unique capacity for modern symbolic thought, “the human capacity,” long before what was previously understood.

The cave stones are what archaeologists term art mobilier —small-scale prehistoric art that is moveable. But mobile art, and rock art generally, is not unique to Africa. Rock art is a global phenomenon that can be found across the World—in Europe, Asia, Australia, and North and South America. While we cannot know for certain what these early humans intended by the things that they made, by focusing on art as the product of humanity’s creativity and imagination we can begin to explore where, and hypothesize why, art began.

Additional resources:

African Rock Art on the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

“Homo Sapiens,” from Becoming Human

British Museum – Rock Art and the Origins of Art in Africa

Namibia from the TARA, the Trust for African Rock Art

Bradshaw Foundation – Africa Rock Art Archive

John Masson, “Apollo 11 Cave in Southwest Namibia: Some Observations on the Site and its Rock Art,” The South African Archaeological Bulletin 61, no. 183 (2006), pp. 76-89.

Ralf Vogelsang, “The Rock-Shelter “Apollo 11” – Evidence of Early Modern Humans in South-Western Namibia,” in Heritage and Cultures in Modern Namibia – In-depth Views of the Country, edited by Cornelia Limpricht and Megan Biesele (Göttingen, Windhoek-Namibia: Klaus Hess Publishers, 2008), pp. 183-196.

W. E. Wendt, “‘Art Mobilier’ from the Apollo 11 Cave, South West Africa: Africa’s Oldest Dated Works of Art,” The South African Archaeological Bulletin vol. 31, no. 121/122 (1976), pp. 5-11.

The art of South Africa

Over the last two centuries, artists in South Africa have responded to European colonialism in different ways.

19th - 20th century

Married Woman’s Apron (Ndebele peoples)

This five-paneled garment is known as an ijogolo, a bridal apron worn by Ndebele women. Upon marriage, the groom’s family traditionally gave the bride a plain leather or canvas apron with five flaps. The newly married Ndebele woman embroidered that apron, creating bold geometric designs with imported glass beads. She would wear this apron on important ceremonial occasions to signify her married status. The multiple panels, referred to as “calves,” symbolize the future children the woman will bear.

Throughout southern Africa, peoples wear beaded garments that comment upon their stage in life and convey aspects of their individual identity. Different types of beaded artifacts may communicate social and marital status, number of children, and a person’s home region or ethnicity.

Although the historical origins of southern African beadwork are uncertain, it is known that glass beads from Europe were available in the area as early as the sixteenth century through trade with the Portuguese. During the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the region became the world’s largest consumer of glass beads. Dating beaded works is difficult, although the color and size of the beads, the patterns and motifs, and the material used can all provide some indication of age. Older works typically have leather backings and use mostly small, white beads with minimal color designs, as in this example.

© 2006 The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (by permission)

Additional resources:

William Kentridge, drawing from Tide Table (Soho in Deck Chair)

by JOSH R. ROSE

On the beach, but in a suit

It is a humorously discordant image: a man in a pinstriped suit sits on a deck chair at the beach, ignoring the overcast vista by reading a newspaper. The figure’s balding head and newspaper are the brightest highlights against the smooth, rippling surf. South African artist William Kentridge has said the inspiration for this scene was a photograph of his grandfather similarly dressed at a beach near Capetown. The contrast of formal dress and beach setting—while whimsical—also suggests class distinctions and the disconnect between experiencing one’s environment and codification as control: rather than watch the tide, the figure (as we come to find out) reads the newspaper’s tide table (a chart that shows water heights over time for a particular location). The gulf separating understanding and experience in this drawing resonates in much of Kentridge’s imagery and process.

“Successful Failures”

Kentridge was raised by two progressive lawyers in Johannesburg who actively helped disenfranchised South Africans navigate the legal system during the systemic inequalities of apartheid. The harsh racial and socioeconomic conditions in South Africa marked the earliest work Kentridge produced after studying visual art at the Johannesburg Art Foundation and theater at the L’École Internationale de Théâtre Jacques Lecoq in Paris.

Kentridge’s earliest passions were theater and opera (and he has continued working in these areas throughout his career), yet after realizing he was not cut out as an actor, he was “reduced to being an artist.” As he has described it, “Every clear decision I have made was wrong. And the only thing that saved me was what I hadn’t decided.” This deceptively self-deprecating remark adequately describes the intentional openness and mutability of meaning Kentridge has built into his approach.

Process as Performance

The drawing above is the result of a film, Tide Table, the ninth film in the series “Drawings For Projection” begun in 1989. These films utilize a unique stop-motion technique: using a 16mm camera, Kentridge photographs each stage of a drawing on one sheet of paper as he continually modifies it through additions and erasures, often leaving ghostly remnants of previous marks on the page. He even periodically appears within the frame, such as by placing a new sheet in front of the camera when the previous drawing/scene is finished.

The resulting work of art is generally comprised of two elements: an animated film and a series of drawings. Unlike traditional animation, which is painstakingly planned and comprised of thousands of single images each denoting a fraction of a second, Kentridge’s films develop organically without any preparatory planning like storyboards, relying more on a stream-of-consciousness approach that strives for something between random chance and conscious premeditation. Kentridge associates this with the concept of “fortuna,” in which his imagery and narrative are influenced by objects in his environment or ideas and motions that seem intrinsically related to—but independent of—the themes and narrative being tackled at the time. The relationship might be comparable to that of authors noting how their characters do something unexpected in the course of writing a novel. There is a performative quality to Kentridge’s process, predicated by the spontaneity he fosters, his own appearances in the frame, and the film itself as a time-based record of his drawing process.

The Traces Always Remain

Kentridge’s drawings for his films are often regarded as palimpsests. A palimpset is the word for a manuscript where the original text has been erased and overwritten (a practice common before paper was available and when parchment was expensive). In Kentridge’s work, the sheet of paper becomes the locus for layer upon layer of images that evolve and shift, where the earlier states of the drawing exist only through traces intentionally left on the paper. In the film, these traces help intensify the movement of his figures, but also visually remark upon the process as a physical interaction of charcoal and eraser on paper.

The palimpsest quality to Kentridge’s approach is one that many critics and historians have associated with his reaction to growing up during a turbulent and shifting period in South African history. Apartheid, legalized racial discrimination, dominated South African governance and society from 1948 until 1994. One way Kentridge has made overt reference to the atrocities of apartheid in his “Drawings for Projection” series is through the one pre-determined facet of these narratives: an established “cast” featuring the wealthy white real-estate developer and industrialist Soho Eckstein. Eckstein represents the authoritative oppressors ruling over black South Africans.

In the 1990 film Monument, for example, Eckstein unveils a heroic monument showing a black worker struggling to carry a load of pristine marble objects. An ostensibly commemorative sculpture to the efforts of South Africans is revealed later to be an actual living person, not a sculpture. Racial discrimination is starkly reduced to the contrast between the “sculpted” worker’s body and the white classically-styled load he bears.

In the 1991 film, Mine, a similar contrast is presented between Eckstein’s white bed coverings and tray as he enjoys coffee, and the grueling, dank conditions of the mines that Eckstein owns. The two are linked visually by the downward action of the French-press coffee maker that becomes the elevator within the mines. Such contrasts seem intentionally provocative, both formally and thematically. Yet Kentridge admits that the decision to have the coffee plunger become the elevator shaft was another example of fortuna, inspired simply from the fact he had that type of coffee maker in his studio that day.

A critical event linked to the legal dissolution of apartheid in the 1990s was the establishment of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Chaired by Archbishop Desmond Tutu, the Commission was a five year investigation into the crimes and human rights abuses committed under apartheid from 1960 until May 10, 1994. The results of the investigation, broadcast on South African television, were intended to bring to light crimes committed and the breadth of the structure of racism and disenfranchisement.

Although Kentridge’s process was established several years before the Commission, scholars like Jessica Dubow and Ruth Rosengarten have linked the palimpsest quality of Kentridge’s “Drawings for Projection” with the contradictory nature of the Commission: although the broadcasts intended to reveal atrocities, they also established that the harrowing acts revealed were firmly “in the past” and therefore not reflective of the dawn of a post-apartheid South Africa. Dubow and Rosengarten suggest that Kentridge’s palimpsest technique is reminiscent of the Commission’s attempts to show—but also remove—traces of apartheid and that Kentridge’s “finished” drawings similarly do not fully reveal everything that went into making them. The documentation of every stage of the drawing is only seen in the animated film, hence the reason the drawings and the films are intrinsically related and should not be separated.

Tide Table

The disconnect between documentation and direct experience seen in the hearings of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission is also central to the drawing of Soho Eckstein sitting at the beach in a business suit. In the films he created after 1994, Kentridge presents Soho as a man whose life has fallen apart: between inexplicable health issues, violent nightmares, and the loss of his fortune, Kentridge portrays Eckstein’s struggles in post-apartheid South Africa. Throughout Tide Table the artist provides a subtext that reflects upon youth, as a choir on the beach sings and a young boy dances and leaps in the surf. Often this occurs around Eckstein, as he sits in the deck chair, seeming to prefer the analytical table of tide flows in the newspaper and, in a later scene, pointedly placing the newspaper over his head to sleep (see above).

These images reinforce Eckstein’s character as one who is more comfortable at a remove from human connection and the natural world, a portrayal that is common to many of the films in the series.

Eckstein’s actions in Tide Table evoke a sense of loss for the comforts and advantages the character had during apartheid. Still, there is a glimmer of hope. Ultimately Eckstein observes those around him; he gets up, and playfully throws a rock into the water.

Additional Resources:

The artist discussing his 2003 film, Tide Table (SFMOMA)

The artist discusses his process (SFMOMA)

This film at SFMOMA

Zimbabwe

Great Zimbabwe

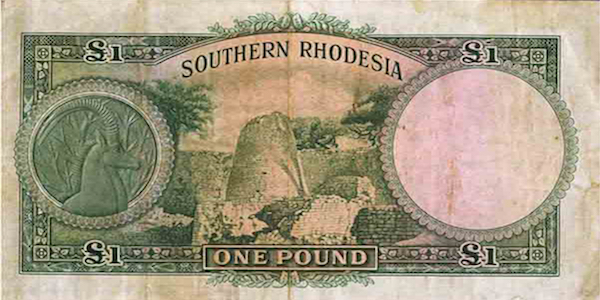

Great Zimbabwe has been described as “one of the most dramatic architectural landscapes in sub-Saharan Africa.”1 It is the largest stone complex in Africa built before the modern era, aside from the monumental architecture of ancient Egypt. The ruins that survive are a four-hour drive south of Zimbabwe’s present-day capital of Harare. It was constructed between the 11th and 15th centuries and was continuously inhabited by the Shona peoples until about 1450 (the Shona are the largest ethnic group in Zimbabwe). But Great Zimbabwe was by no means a singular complex—at the site’s cultural zenith, it is estimated that seven comparable states existed in this region.

The word zimbabwe translates from the Bantu language of the Shona to either “judicial center” or “ruler’s court or house.” A few individual zimbabwes (houses) have survived exposure to the elements over the centuries. Within these clay structures, excavations have revealed interior furnishings such as pot-stands, elevated surfaces for sleeping and sitting, as well as hearths. Taken together, the settlement encompasses a cluster of approximately 250 royal houses built of clay, which in addition to other multi-story clay and thatch homes would have supported as many as 20,000 inhabitants—a exceptional scale for a sub-Saharan settlement at this time.

The stone constructions of Great Zimbabwe can be categorized into roughly three areas: the Hill Ruin (on a rocky hilltop), the Great Enclosure, and the Valley Ruins (map below). The Hill Ruin dates to approximately 1250, and incorporates a cave that remains a sacred site for the Shona peoples today. The cave once accommodated the residence of the ruler and his immediate family. The Hill Ruin also held a structure surrounded by 30-foot high walls and flanked by cylindrical towers and monoliths carved with elaborate geometric patterns.

Site plan of Great Zimbabwe (modified from an original plan by National Museums and Monuments ofZimbabwe) from Shadreck Chirikure and Innocent Pikirayi, “Inside and outside the dry stone walls: Revisiting the material culture of Great Zimbabwe,” Antiquity 82 (December 2015), pp. 976-993. The letters refer to the types of stone construction (see figure 4).

The Great Enclosure was completed in approximately 1450, and it too is a walled structure punctuated with turrets and monoliths, emulating the form of the earlier Hill Ruin. The massive outer wall is 32 feet high in some places. Inside the Great Enclosure, a smaller wall parallels the exterior wall creating a tight passageway leading to large towers. Because the Great Enclosure shares many structural similarities with the Hill Ruin, one interpretation suggests that the Great Enclosure was built to accommodate a surplus population and its religious and administrative activities. Another theory posits that the Great Enclosure may have functioned as a site for religious rituals.

The third section of Great Zimbabwe, the Valley Ruins, include a number of structures that offer evidence that the site served as a hub for commercial exchange and long distance trade. Archaeologists have found porcelain fragments originating from China, beads crafted in southeast Asia, and copper ingots from trading centers along the Zambezi River and from Central African kingdoms.2

A monolithic soapstone sculpture of a seated bird resting on atop a register of zigzags was unearthed here. The pronounced muscularity of the bird’s breast and its defined talons suggest that this represents a bird of prey, and scholars have conjectured it could have been emblematic of the power of Shona kings as benefactors to their people and intercessors with their ancestors.

Conical tower

All of the walls at Great Zimbabwe were constructed from granite hewn locally. While some theories suggest that the granite enclosures were built for defense, these walls likely had no military function. Many segments within the walls have gaps, interrupted arcs or elements that seem to run counter to needs of protection. The fact that the structures were built without the use of mortar to bind the stones together supports speculation that the site was not, in fact, intended for defense. Nevertheless, these enclosures symbolize the power and prestige of the rulers of Great Zimbabwe.

The conical tower (above) of Great Zimbabwe is thought to have functioned as a granary. According to tradition, a Shona ruler shows his largess towards his subjects through his granary, often distributing grain as a symbol of his protection. Indeed, advancements in agricultural cultivation among Bantu-speaking peoples in sub-Saharan Africa transformed the pattern of life for many, including the Shona communities of present-day Zimbabwe.

Wealth and trade

Archaeological debris indicate that the economy of Great Zimbabwe relied on the management of livestock. In fact, cattle may have allowed the Shona peoples to move from subsistence agriculture to mining and trade. Iron tools have been found on site, along with copper, and gold wire jewelry and ornaments. Great Zimbabwe is thought to have prospered, perhaps indirectly, from gold that was mined 25 miles from the city and that was transported to the Indian Ocean port at Sofala (below) where it made its way by dhow (sailing vessels), up the coast, and by way of Kilwa Kisiwani, to the markets of Cairo.

By about 1500, however, Great Zimbabwe’s political and economic influence waned. Speculations as to why this occurred point to the frequency of droughts and environmental fragility, though other theories stress that Great Zimbabwe might have experienced political skirmishes over political succession that interrupted trade, still other theories hypothesize disease that may have afflicted livestock.3

Great Zimbabwe stands as one of the most extensively developed centers in pre-colonial sub-Saharan Africa and stands as a testament to the organization, autonomy, and economic power of the Shona peoples. The site remains a potent symbol not only to the Shona, but for Zimbabweans more broadly. After gaining independence from the British, the nation formerly named after the British industrialist and imperialist, Cecil Rhodes, was renamed Zimbabwe.

1. Webber Ndoro, The Preservation of Great Zimbabwe: Your Monument, Our Shrine (ICCROM, 2005), p. 16.

2. Peter Garlake, Early Art and Architecture of Africa (Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, 2002), p. 153.

3. Garlake, 157.

Video \(\PageIndex{1}\)

Additional resources:

Great Zimbabwe World Heritage Site (UNESCO)

Great Zimbabwe student worksheet (The British Museum)

Great Zimbabwe on the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Webber Ndoro, The Preservation of Great Zimbabwe: Your Monument, Our Shrine (ICCROM, 2005)

—–. The Soapstone Birds from Great Zimbabwe, African Arts, 18 (May 1985), pp. 68-73.

Great Zimbabwe from Scientific American

Peter S. Garlake, Great Zimbabwe (Stein & Day Pub, 1973).