7.15: Late 18th century- Neoclassicism

- Page ID

- 73380

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Neoclassicism

France was on the brink of its first revolution in 1789.

late 1700s

Neoclassicism, an introduction

In opposition to the frivolous sensuality of Rococo painters like Jean-Honoré Fragonard and François Boucher, the Neoclassicists looked back to the French painter Nicolas Poussin for their inspiration (Poussin’s work exemplifies the interest in classicism in French art of the seventeenth century ). The decision to promote “Poussiniste” painting became an ethical consideration—they believed that strong drawing was rational, therefore morally better. They believed that art should be cerebral, not sensual.

The Neoclassicists, such as Jacques-Louis David (pronounced Da-VEED), preferred the well-delineated form—clear drawing and modeling (shading). Drawing was considered more important than painting. The Neoclassical surface had to look perfectly smooth—no evidence of brush-strokes should be discernible to the naked eye.

France was on the brink of its first revolution in 1789, and the Neoclassicists wanted to express a rationality and seriousness that was fitting for their times. Artists like David supported the rebels through an art that asked for clear-headed thinking, self-sacrifice to the State (as in Oath of the Horatii) and an austerity reminiscent of Republican Rome.

Neoclassicism was a child of the Age of Reason (the Enlightenment), when philosophers believed that we would be able to control our destinies by learning from and following the laws of nature (the United States was founded on Enlightenment philosophy). Scientific inquiry attracted more attention. Therefore, Neoclassicism continued the connection to the Classical tradition because it signified moderation and rational thinking but in a new and more politically-charged spirit (“neo” means “new,” or in the case of art, an existing style reiterated with a new twist.)

Neoclassicism is characterized by clarity of form, sober colors, shallow space, strong horizontal and verticals that render that subject matter timeless (instead of temporal as in the dynamic Baroque works), and Classical subject matter (or classicizing contemporary subject matter).

Additional resources:

Neoclassicism on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Nicolas Poussin on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

The Age of Enlightenment, an introduction

by DR. STEVEN ZUCKER and DR. BETH HARRIS

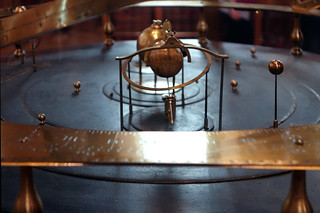

In the painting above by Joseph Wright of Derby, we see an orrery— a mechanical model of the solar system. In the center is a gas light which represents the sun (though the child who stands in the foreground with his back to us block this from our view); the arcs represent the orbits of the planets. Wright concentrates on the faces of the figures to create a compelling narrative.

With paintings like these, Wright invented a new subject: scenes of experiments and new machinery. This was the beginning of the Industrial Revolution (think cities, railroads, steam power, gas and then electric light, factories, and machines). Wright’s fascination with light, strange shadows, and darkness, reveals the influence of Baroque art.

Enlightenment

Toward the middle of the eighteenth century a shift in thinking occurred. This shift is known as the Enlightenment. You have probably already heard of some important Enlightenment figures, like Rousseau, Diderot and Voltaire. It is helpful I think to think about the word “enlighten” here—the idea of shedding light on something, illuminating it, making it clear.

The thinkers of the Enlightenment, influenced by the scientific revolutions of the previous century, believed in shedding the light of science and reason on the world in order to question traditional ideas and ways of doing things. The scientific revolution (based on empirical observation, and not on metaphysics or spirituality) gave the impression that the universe behaved according to universal and unchanging laws (think of Newton here). This provided a model for looking rationally on human institutions as well as nature.

Reason and equality

Rousseau, for example, began to question the idea of the divine right of Kings. In The Social Contract, he wrote that the King does not, in fact, receive his power from God, but rather from the general will of the people. This, of course, implies that “the people” can also take away that power.

The Enlightenment thinkers also discussed other ideas that are the founding principles of any democracy—the idea of the importance of the individual who can reason for himself, the idea of equality under the law, and the idea of natural rights. The Enlightenment was a period of profound optimism, a sense that with science and reason—and the consequent shedding of old superstitions—human beings and human society would improve.

You can probably tell already that the Enlightenment was anti-clerical; it was, for the most part, opposed to traditional Catholicism. Instead, the Enlightenment thinkers developed a way of understanding the universe called Deism—the idea, more or less, is that there is a God, but that this God is not the figure of the Old and New Testaments, actively involved in human affairs. He is more like a watchmaker who, once he makes the watch and winds it, has nothing more to do with it.

The Enlightenment, the monarchy, and the French Revolution

The Enlightenment encouraged criticism of the corruption of the monarchy (at this point King Louis XVI), and the aristocracy. Enlightenment thinkers condemned Rococo art for being immoral and indecent, and called for a new kind of art that would be moral instead of immoral, and teach people right and wrong.

Denis Diderot, Enlightenment philosopher, writer and art critic, wrote that the aim of art was “to make virtue attractive, vice odious, ridicule forceful; that is the aim of every honest man who takes up the pen, the brush or the chisel” (Essai sur la peinture).

These new ways of thinking, combined with a financial crisis (the country was bankrupt) and poor harvests left many ordinary French people both angry and hungry. In 1789, the French Revolution began. In its initial stage, the revolutionaries asked only for a constitution that would limit the power of the king.

Ultimately the idea of a constitution failed, and the revolution entered a more radical stage. In 1792 King Louis XVI and his wife Marie Antoinette were deposed and ultimately beheaded along with thousands of other aristocrats believed to be loyal to the monarchy.

Additional resources:

The Enlightenment from The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

The Enlightenment from Professor Paul Brian at Washington State University

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Jacques-Louis David

Jacques-Louis David, Oath of the Horatii

Video \(\PageIndex{1}\): Jacques-Louis David, Oath of the Horatii, 1784, oil on canvas, 3.3 x 4.25 m, painted in Rome, exhibited at the salon of 1785 (Musée du Louvre)

No one had seen a painting like it

In 1785 visitors to the Paris Salon were transfixed by one painting, Jacques-Louis David’s Oath of the Horatii. It depicts three men, brothers, saluting toward three swords held up by their father as the women behind him grieve—no one had ever seen a painting like it. Similar subjects had always been seen in the Salons before but the physicality and intense emotion of the painting was new and undeniable. The revolutionary painting changed French art but was David also calling for another kind of revolution—a real one?

Conquer or die

The story of Oath of the Horatii came from a Roman legend first recounted by the Roman historian Livy involving a conflict between the Romans and a rival group from nearby Alba. Rather than continue a full-scale war, they elect representative combatants to settle their dispute. The Romans select the Horatii and the Albans choose another trio of brothers, the Curatii. In the painting we witness the Horatii taking an oath to defend Rome.

The women know that they will also bear the consequence of the battle because the two families are united by marriage. One of the wives in the painting is a daughter of the Curatii and the other, Camilla, is engaged to one of the Curatii brothers. At the end of the legend the sole surviving Horatii brother kills Camilla, who condemned his murder of her beloved, accusing Camilla of putting her sentiment above her duty to Rome. The moment David chose to represent was, in his reported words, “the moment which must have preceded the battle, when the elder Horatius, gathering his sons in their family home, makes them swear to conquer or die.”

A rigorously organized painting

To tell the story of the oath, David created a rigorously organized painting with a scene set in what might be a Roman atrium dominated by three arches at the back that keep our attention focused on the main action in the foreground. There we see a group of three young men framed by the first arch, the Horatii brothers, bound together with their muscled arms raised in a rigid salute toward their father framed by the central arch. He holds three swords aloft in his left hand and raises his right hand signifying a promise or sacrifice. The male figures create tense, geometric forms that contrast markedly with the softly curved, flowing poses of the women seated behind the father. David lit the figures with a stark, clinical light that contrasts sharply with the heightened drama of the scene as if he were requiring the viewer to respond to the scene with a mixture of passion and rationality.

An example of Neoclassicism

In beginning art history courses, the painting is typically presented as a prime example of Neoclassical history painting. It tells a story derived from the Classical world that provides an example of virtuous behavior (exemplum vertutis). The dramatic, rhetorical gestures of the male figures easily convey the idea of oath-taking and the clear, even light makes every aspect of the story legible. Instead of creating an illusionistic extension of space into a deep background, David radically cuts off the space with the arches and pushes the action to the foreground in the manner of Roman relief sculpture.

Before Oath of the Horatii, French history paintings in a more Rococo style such as Jean-François-Pierre Peyron’s Death of Alcestis (1785) involved the viewer by appealing to sentiment and presenting softly modeled graceful figures. David acknowledged that old approach in the figures of the women in Oath of the Horatii, but challenged it with the starkly athletic figures and resolute poses of the men.

Going back to Poussin

Before composing Oath of the Horatii, David went to see Poussin’s Rape of the Sabine Women and employed the lictor, the caped man, on the far left as the basis for the Horatii and he directly quoted other figures from Poussin as well. Even though Poussin was his model, David knew that he was creating a new type of painting and wrote, “I do not know whether I shall ever paint another like it,” as he developed the austere composition and powerful physiques.

Personal sacrifice for an ideal

Today the painting is typically interpreted in the context of the French Revolution and David’s own direct involvement as a revolutionary. The exact source of the scene that inspired David is in doubt but it is important to art historians because it can offer clues as to David’s intentions for the picture.

In the nineteenth century a former student of David identified the source as the 1640 play Les Horaces by Corneille that David had seen in Paris in 1782. The difficulty is that no scene of an oath occurs in Corneille’s script. However, toward the end of the play, a minor character comes on stage bearing the three swords of the defeated Curatii. This stage direction as well as other contemporary productions and images related to the story of Horatii in particular—and oath-taking in general—may provide the background for David’s decision to paint the moment when the brothers take their oath to defend Rome—an act of personal sacrifice for a political ideal.

Revolutionary or not?

With this in mind, we can understand how one might read Oath of the Horatii as a painting designed to rally republicans (those who believed in the ideals of a republic, and not a monarchy, for France) by telling them that their cause will require the dedication and sacrifice of the Horatii. Those who support this view cite some of the rousing lines from Corneille’s tragedy such as, “Before I am yours, I belong to my country,” as well as the response of contemporary left-wing writers who praised David’s republican sentiments. Those who disagree with this interpretation argue that David was enmeshed in the system of royal patronage, that the painting was accepted into the Salon with no negative response from official quarters and later royal commissions followed.

In the succeeding decades French painters responded again and again to David’s transformative painting. Paintings such as Gros’ Napoleon Bonaparte Visiting the Plague-Stricken (1804), Gericault’s Raft of the Medusa (1819), Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People (1830), and even Courbet’s Burial at Ornans (1849) confront the Oath of Horatii as they embrace or reject David’s aesthetic and, perhaps, political revolution.

Additional resources:

This painting on the Google Art Project

Anita Brookner, Jacques-Louis David (London: Thames and Hudson, 1980).

Thomas Crow, Painters and Public Life in Eighteenth-century Paris (New Haven and London: Yale UP, 1985).

Dorothy Johnson, “Corporality and Communication: The Gestural Revolution of Diderot, David, and the Oath of the Horatii.” Art Bulletin 71 (March 1989), pp. 92-113.

Andrew Stewart, “David’s Oath of the Horatii and the Tyrannicides.” The Burlington Magazine 143, no. 1177 (April 2001), pp. 212-219.

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

David, The Lictors Returning to Brutus the Bodies of His Sons

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{2}\): Jacques-Louis David, The Lictors Returning to Brutus the Bodies of His Sons, 1789, oil on canvas, 10′ 7-1/8″ x 13′ 10-1/8″ / 3.23 x 4.22m (Musée du Louvre, Paris)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

David, Study for The Lictors Bringing Brutus the Bodies of his Sons

by THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART

Video \(\PageIndex{3}\): Jacques-Louis David, Study for The Lictors Bringing Brutus the Bodies of his Sons, 1787, black chalk, pen and black and brown ink, brush and gray and brown wash, heightened with white gouache, 13 1/16 x 16 9/16″ / 33.2 x 42.1 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York). Video from The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Additional resources:

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

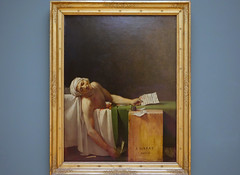

Jacques-Louis David, The Death of Marat

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{4}\): Jacques-Louis David, The Death of Marat, 1793, oil on canvas, 65 x 50-1/2″ (Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, Brussels)

David and the Jacobins

By 1793, the violence of the Revolution dramatically increased until the beheadings at the Place de la Concorde in Paris became a constant, leading a certain Dr. Joseph Guillotine to invent a machine that would improve the efficiency of the ax and block and therefore make executions more humane. David was in thick of it. Early in the Revolution he had joined the Jacobins, a political club that would in time become the most rabid of the various rebel factions. Led by the ill-fated Georges Danton and the infamous Maximilien Robespierre, the Jacobins (including David) would eventually vote to execute Louis XVI and his Queen Marie Antoinette who were caught attempting to escape across the border to the Austrian Empire.

Marat and Christ

At the height of the Reign of Terror in 1793, David painted a memorial to his great friend, the murdered publisher, Jean Marat. As in his Death of Socrates, David substitutes the iconography (symbolic forms) of Christian art for more contemporary issues. In Death of Marat, 1793, an idealized image of David’s slain friend, Marat, is shown holding his murderess’s (Charlotte Corday) letter of introduction. The bloodied knife lays on the floor having opened a fatal gash that functions, as does the painting’s very composition, as a reference to the entombment of Christ and a sort of secularized stigmata (reference to the wounds Christ is said to have received in his hands, feet and side while on the cross). Is David attempting now to find revolutionary martyrs to replace the saints of Catholicism (which had been outlawed)?

David and Napoleon

By 1794 the Reign of Terror had run its course. The Jacobins had begun to execute not only captured aristocrats but fellow revolutionaries as well. Eventually, Robespierre himself would die and the remaining Jacobins were likewise executed or imprisoned. David escaped death by renouncing his activities and was locked in a cell in the former palace, the Louvre, until his eventual release by France’s brilliant new ruler, Napoleon Bonaparte. This diminutive Corsican had been the youngest general in the French army and during the Revolution had become a national hero by waging a seemingly endless string of victorious military campaigns against the Austrians in Belgium and Italy. Eventually, Napoleon would control most of Europe, crown himself emperor, and would release David in recognition that the artist’s talent could serve the ruler’s purposes.

Additional resources:

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Jacques-Louis David, The Intervention of the Sabine Women

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Video \(\PageIndex{5}\): Jacques-Louis David, The Intervention of the Sabine Women, 1799, oil on canvas, 12’8″ x 17’3/4″ / 3.85 x 5.22 m (Musée du Louvre, Paris)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

Jacques-Louis David, Napoleon Crossing the Alps

by BEN POLLITT

Some find it stiff and lifeless, proof of David’s ineptness at capturing movement. Some see it not as art, but propaganda, pure and simple. Some snigger at its overblown, action-packed, cliff-hanging momentousness, with shades of “Hi ho Silver, away!” Some have it down as a sort of beginning of the end moment in David’s career, before he officially became Napoleon’s artist-lackey. Whatever one might say, though (and a lot has been said about Napoleon Crossing the Alps), it is still arguably the most successful portrait of Napoleon Bonaparte that was ever made. Personally, I love it.

Background

Completed in four months, from October 1800 to January 1801, it signals the dawning of a new century. After a decade of terror and uncertainty following the Revolution, France was emerging as a great power once more. At the heart of this revival, of course, was General Napoleon Bonaparte who, in 1799, had staged an uprising against the revolutionary government (a coup d’état), installed himself as First Consul, and effectively become the most powerful man in France (a few years later he will declare himself emperor).

In May 1800 he led his troops across the Alps in a military campaign against the Austrians which ended in their defeat in June at the Battle of Marengo. It is this achievement the painting commemorates. The portrait was commissioned by Charles IV, then King of Spain, to be hung in a gallery of paintings of other great military leaders housed in the Royal Palace in Madrid.

Napoleon and the portrait

Famously, Napoleon offered David little support in executing the painting. Refusing to sit for it, he argued that: “Nobody knows if the portraits of the great men resemble them, it is enough that their genius lives there.” All David had to work from was an earlier portrait and the uniform Napoleon had worn at Marengo. One of David’s sons stood in for him, dressed up in the uniform and perched on top of a ladder. This probably accounts for the youthful physique of the figure.

Napoleon, however, was not entirely divorced from the process. He was the one who settled on the idea of an equestrian portrait: “calme sur un cheval fougueux” (calm on a fiery horse), were his instructions to the artist. And David duly obliged. What better way, after all, to demonstrate Napoleon’s ability to wield power with sound judgment and composure. The fact that Napoleon did not actually lead his troops over the Alps but followed a couple of days after them, traveling on a narrow path on the back of a mule is not the point!

Description

Like many equestrian portraits, a genre favored by royalty, Napoleon Crossing the Alps is a portrait of authority. Napoleon is pictured astride a rearing Arabian stallion. Before him to his left we see a mountain, while in the background, largely obscured by rocks, French troops haul along a large canon and further down the line fly the tricolore (the national flag of France) .

Bonaparte’s gloveless right hand points up towards the invisible summit, more for us to follow, one feels, than the soldiers in the distance. Raised arms are often found in David’s work, though this one is physically connected with the setting, echoing the slope of the mountain ridge. Together with the line of his cloak, these create a series of diagonals that are counterbalanced by the clouds to the right. The overall effect is to stabilize the figure of Napoleon.

The landscape is treated as a setting for the hero, not as a subject in itself. On the rock to the bottom left (below), for instance, the name of Napoleon is carved beside the names of Hannibal and Charlemagne—two other notable figures who led their troops over the Alps. David uses the landscape then to reinforce what he wishes to convey about his subject. In terms of scale alone, Napoleon and his horse dominate the pictorial plane. Taking the point further, if with that outstretched arm and billowing cloak, his body seems to echo the landscape, the reverse might equally hold true, that it is the landscape that echoes him, and is ultimately mastered by his will. David seems to suggest that this man, whose achievements will be celebrated for centuries to come, can do just about anything.

Napoleon was obviously flattered. He ordered three more versions to be painted; a fifth was also produced which stayed in David’s studio. Reflecting the breadth of Napoleon’s European conquests, one was hung in Madrid, two in Paris, and one in Milan.

Conclusion

In 1801 David was awarded the position of Premier Peintre (First Painter) to Napoleon. One may wonder how he felt about this new role. Certainly David idolized the man. Voilà mon héros (here is my hero), he said to his students when the general first visited him in his studio. And perhaps it was a source of pride for him to help secure Napoleon’s public image. Significantly, he signs and dates Napoleon Crossing the Alps on the horse’s breastplate, a device used to hold the saddle firmly in place. The breastplate also serves as a constraint, though, and given his later huge commissions, such as The Coronation of Napoleon, one wonders if David’s creative genius was inhibited as a result of his hero’s patronage.

In Napoleon Crossing the Alps, however, the spark is still undeniably there. Very much in accord with the direction his art was taking at the time, “a return to the pure Greek” as he put it. In it he molds the image of an archetype, the sort one finds on medals and coins, instantly recognizable and infinitely reproducible, a hero for all time.

Additional resources:

Key Paintings from the First Empire from The Fondation Napoléon

Dan Cruickshank, “Napoleon, Nelson and the French Threat,” BBC History (2011)

Napoleon Bonaparte on BBC History

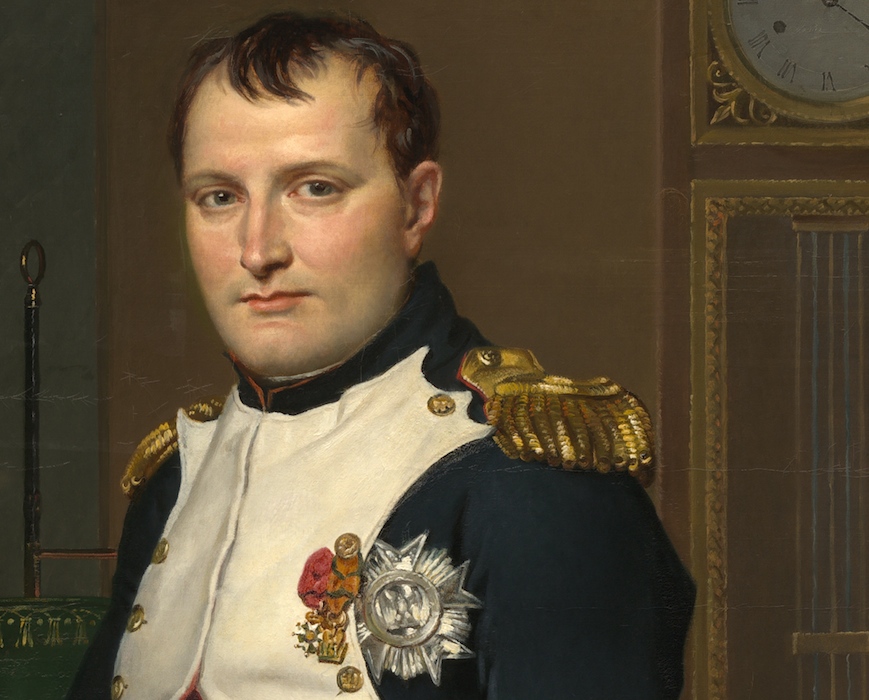

David, The Emperor Napoleon in His Study in the Tuileries

At the beginning of the movie The Godfather, Michael Corleone (played by Al Pacino) wants nothing to do with his family’s involvement in organized crime. When telling a family story to his girlfriend, he concludes, “That’s my family, Kay, That’s not me.” As the film progresses, however, Michael’s father and older brother are the focus of violent attacks and Michael becomes more active in the family business until—at the end of the film—he has assumed the leadership of the Corleone crime syndicate by killing all of his enemies. Fictional characters—both in film and in novels—have arcs. They change through time. The same is true of real characters from history. They often have a rise, but just as often there is a precipitous fall. Napoleon Bonaparte is but one example.

A visual starting point could be Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres’s 1806 painting, Napoleon on His Imperial Throne (above). In this work, Ingres painted Napoleon as if he were an omnipotent ruler—rather than a mere mortal. But six years later, Jacques-Louis David (Ingres’s former teacher), painted The Emperor Napoleon in His Study in the Tulieries (1812). These two portraits—painted just six years apart—show a significant arc in the life and career of Napoleon.

Alexander Hamilton, the Tenth Duke of Hamilton (and sadly, of no relationship to the de facto leader of the Federalist Party in the United States with whom he shares a name) commissioned David to paint The Emperor Napoleon in His Study in the Tulieries in 1811.

Finished the following year, it shows a standing Napoleon, about three-quarters life-sized. He slightly turns his face to look at the viewer, and his right hand is tucked into his uniform jacket (to this day, some jackets often have a vertically zippered pocket on the left side; this is called a Napoleon pocket).

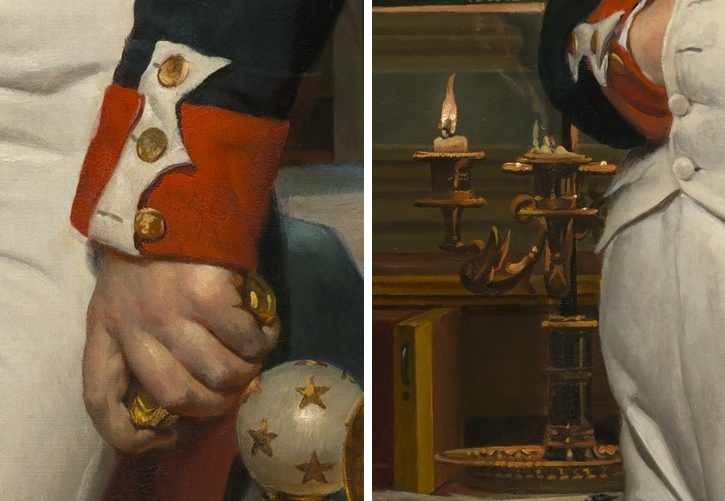

The blue jacket with the white facing and red upturned cuffs and the gold epaulettes identify him as a colonel in the Imperial Guard Foot Grenadiers—a group of elite soldiers that Napoleon personally commanded. The two medals pinned to Napoleon’s left breast speak to the scope of his rule. The leftmost of the two is the Order of the Iron Crown, an organization Napoleon founded in 1805 as the King of Italy. The second medal is that of the French Legion of Honor.

Napoleon’s uniform is completed with white knee breeches and stockings, and black shoes with gold buckles. Although he wears a military uniform, this is hardly a military portrait. He has discarded his officer’s sword—it rests on the chair on the right side of the painting—and Napoleon is shown doing the administrative work of a civic leader. He stands between the high-backed red velvet chair on the right and in front of the Empire-styled desk behind him. A gilded regal lion serves as the visible leg of the desk, and an ink-stained quill, candle-lit lamp, and various papers can be seen atop his writing table.

A rolled up sheet of paper with the letters COD can be seen on the right side of the desk. This detail alludes to the Napoleonic Code—the French civil law code Napoleon established in 1804. The bees, which resemble an upside-down fleurs-de-lys, can be seen in the velvet that covers the chair (both the bee and the fleur de lys were symbols of the French monarchy).

David has signed and dated the portrait on a rolled up map to the side of the table, a leather-bound volume of Plutarch (in French: Plutarque) is beside it. Plutarch was an ancient Roman biographer and historian, most famous in the nineteenth century as the author of The Parallel Lives, a text that explores the virtues and vices of Greek and Roman rulers, men such as Alexander the Great, Themistocles, Julius Caesar, and Cicero. The inclusion of this book was a way to visually tie Napoleon to the great rulers of the classical past who he so admired. And yet, not everything is perfect within this space.

Although Napoleon stands and looks out towards the viewer, he looks more disheveled than not. His hair—complete with the gray typical of a man in his 50s—appears unkempt and tousled. In addition, his uniform would hardly pass muster. A cuff button has been undone, and his silken stockings and trousers appear wrinkled from being worn for an exceptionally long working day. This fact is alluded to by two time-bearing details. The grandfather clock displays the time as 4:12. And the candles of his desk lamp—one nearly burned to its completing, another recently extinguished, several others seemingly expired—make it clear that it is not the late afternoon, but rather the very early morning. Clearly, time was running short.

This portrait seems to suggest that Napoleon was working too late and too hard at the time it was commissioned, and indeed, Napoleon’s time as a world ruler was coming to a climactic finale. The year the painting was completed—1812—was a particularly calamitous one for Napoleon, as he was in the middle of the disastrous invasion of Russia. Less than two years later, on 4 April 1814, Napoleon abdicated his throne and was exiled to the island of Elba. David skillfully and subtly depicts Napoleon’s transition from omnipotent ruler to fallible commander. In this regards, David’s portrait can be seen as a painted contemporary version of the Greek sculptor Glykon’s statue, The Weary Hercules, a small bronze copy that David likely saw in the Louvre. Like the mighty Hercules, Napoleon had once been an all-powerful leader. But as Hercules had his downfall at the hands of his jealous wife Deianara, so too did Napoleon have his downfall at the hands of the Duke of Wellington. A failed return to power in 1815 caused Napoleon’s permanent banishment to the island of Saint Helena where he died in 1821. David’s portrait of the ruler in his study, thus constitutes one of the last formal portraits of the great French ruler.

Additional resources:

This painting at the National Gallery of Art

Interactive feature on this painting from the National Gallery of Art

Angelica Kauffmann, Cornelia Pointing to her Children as Her Treasures

by DANA MARTIN

A moment of moralizing

To the artists of eighteenth-century Europe, it was not enough to simply paint a beautiful painting. Yes one could marvel at your use of colors, proportions, and how masterfully you draped the fabric on your figures, but this was just not enough. The story that is represented must also improve the viewer and impart a moralizing message. This was a common theme even before the emergence of the Neoclassical trend (for example, Chardin’s canvases of simple French country life or Hogarth’s painted commentaries on the wealthy classes of England). When interest in the ancient cultures of the Mediterranean—more specifically Rome—arose in the mid eighteenth century the moralizing theme segued to also include stories from classical antiquity.

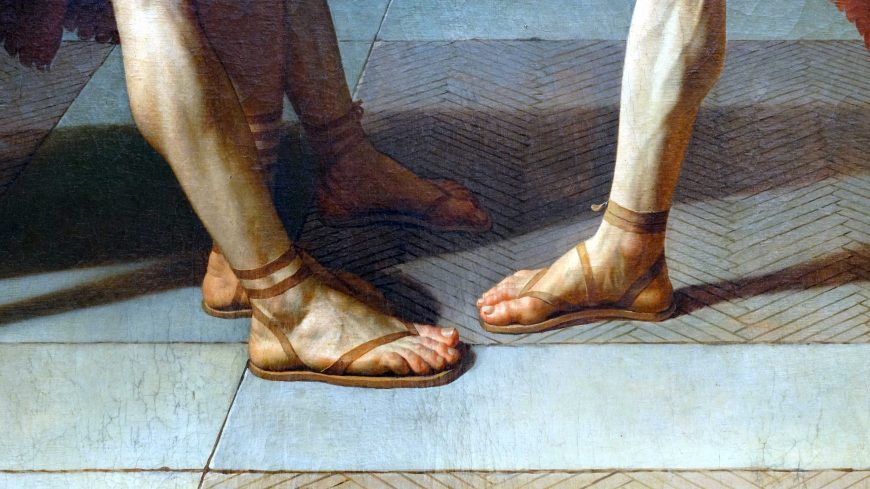

The Swiss-born painter Angelica Kauffmann is just one artist to contribute to this genre. Painted in 1785, Cornelia, Mother of the Gracchi, Pointing to Her Children as Her Treasures, is her subject. Roman architectural influences frame two women portrayed wearing what one can imagine is typical of ancient Roman dress, along with three children, also wearing masterfully draped togas with thin leather sandals. They look like they might have stepped directly off a temple’s pediment.

An example of virtue

If you compare Kauffmann’s simple presentation to the previous Rococo genre, with the lush landscapes, frothy pastel pink frocks, and chubby frolicking cherubs, it is clear that art is going in a different direction. This painting is an exemplum virtutis, or a model of virtue. The story that Kauffmann painted is that of Cornelia, an ancient Roman woman who was the mother of the future political leaders Tiberius and Gaius Gracchus. The brothers Gracchi were politicians in second-century B.C.E. Rome. They sought social reform and were seen as friends to the average Roman citizen. So where did these benefactors of the people learn their exemplary ethics? That would be their mother, Cornelia.

The scene that we see in Kauffmann’s painting illustrates one such example of Cornelia’s teachings. A visitor has come to her home to show off a wonderful array of jewelry and precious gems, what one might call treasures. To her visitor’s chagrin, when she asks Cornelia to reveal her treasures she humbly brings her children forward, instead of running to get her own jewelry box. The message is clear; the most precious treasures of any woman are not material possessions, but the children who are our future. You can almost feel the embarrassment when you look at the face of the visitor, who Kauffmann has smartly painted with a furrowed brow and slightly gaped mouth.

The lure of ancient Rome

Born in 1740, Angelica Kauffmann received a first-rate artistic education from her father, who was a Swiss muralist. She traveled through her native Switzerland, Austria, and eventually Italy where she was able to see the work of the ancient artists with her own eyes. She was following in the tradition of the Grand Tour, the educational excursion that many wealthy Europeans took to marvel and study the art, architecture, and history of ancient Rome.

The interest in ancient Mediterranean cultures was fueled not just by the cultural productions of Rome, but also by the newly discovered remains of the ancient Roman cities of Herculaneum and Pompeii, which were excavated beginning in 1738 and 1748, respectively. Covered by the volcanic ash of Mount Vesuvius in August 79 CE, an almost perfect scene of typical ancient life was preserved. These findings did not just spark a renewed interest in classical antiquity in eighteenth-century art and architecture, but also inspired new fashions, interior design, and even gardens and tableware. This was a find that one must see in person, and Angelica Kauffman was lucky enough to take the Grand Tour like so many of her fellow artists.

Enlightenment ideals

While the geometric symmetry and simplicity of the arts in antiquity might have greatly inspired the work of Kauffman and other Neoclassical artists, these ancient societies also aligned with Enlightenment ideals, which were often seen as the zenith of human civilization. Greece and Rome—it was felt—were the cultures that gave us the enlightened political systems of democracy and republicanism, as opposed to the modern monarchies, which would be increasingly criticized as corrupt and arbitrary in the mid and late eighteenth century. The ancients could instruct modern audiences in patriotism, civic virtue, and ethics, and Kauffmann’s moralizing message is a wonderful example of this trend.

This revival of classical antiquity was a cultural phenomenon that affected not just artistic practices, but also shaped the modern mind. Angelica Kauffman would eventually settle in England where she enjoyed great success as a portrait artist and history painter. In an age that can be described as patriarchal at its best and chauvinistic at its worst, Kauffmann played a major role in the British art scene. She was a regular exhibitor at the prestigious Royal Academy and had many aristocratic and even royal patrons. Cornelia Pointing to Her Children as Her Treasures is truly one of Kauffmann’s most famous treasures, and permanently positioned her as a pioneer of the Neoclassical movement.

Additional resources:

This painting at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

Angelica Kauffmann on the BBC’s “Your Paintings”

Works by Angelica Kauffmann in the National Portrait Gallery

Anne-Louis Girodet, The Sleep of Endymion

by DR. BETH HARRIS and DR. STEVEN ZUCKER

Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\): Anne-Louis Girodet de Roussy-Trioson, The Sleep of Endymion, 1791, oil on canvas, 6′ 5-¾” x 8′ 6-¾” / 1.98 x 2.61 m (Musée du Louvre, Paris)

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

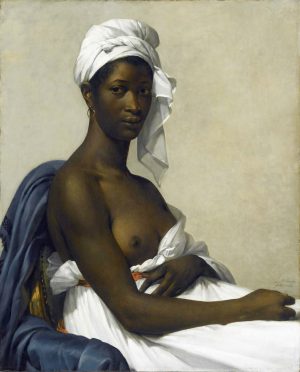

Marie-Guillemine Benoist, Portrait of Madeleine

by DR. SUSAN WALLER

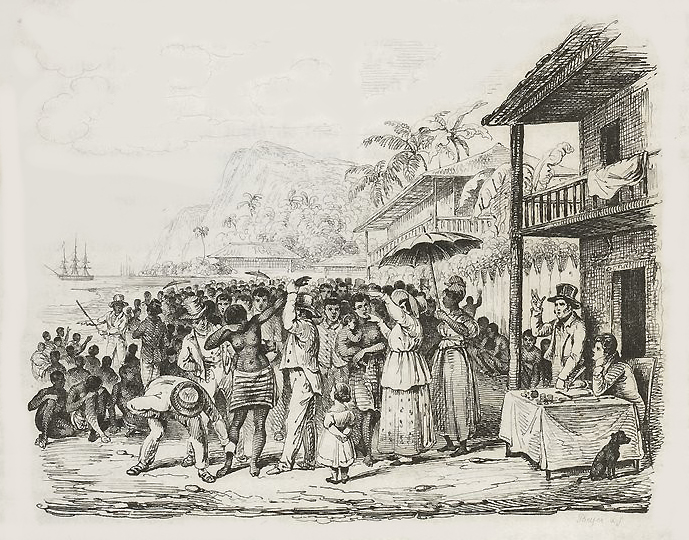

Marie-Guillemine Benoist’s Portrait of Madeleine (formerly known as Portrait of a Negress) hangs today in the Louvre in a gallery devoted to paintings by Jacques-Louis David and his students. It is placed at the center of a wall displaying seven portraits, a location that asserts its importance. In 1800 the work was exhibited in the Louvre for the first time, at the Salon—the state-sponsored presentation of works by contemporary artists. It hung in the Salon Carré, one smallish work on a wall of paintings hung frame to frame, floor to ceiling, as was customary at the time. Contemporary art critics picked it out, but not all were impressed. The critic for a conservative paper derided it as a “noirceur” or “black stain.” Why did this work provoke such a negative response when first exhibited?

A portrait or an allegory?

The painting shows a young black woman seated in an armchair. Her body is oriented to her left, but she turns to face the viewer with a sober and self-possessed expression. The treatment of her face suggests this is a likeness of a particular individual. Most of her hair is covered in an elaborate white headwrap, and she wears a brilliant white garment that slips from her shoulders to reveal the warm dark skin of her right breast. The background is a plain beige field, but the trim on her chair suggests that she is sitting in a well-furnished interior. The only bright colors in this largely monochromatic work are the red of a ribbon holding the white cloth beneath her breasts and the blue of a shawl draped over the back of her chair.

Benoist’s painting is consistent with the conventions of portraiture and the Neoclassical aesthetic prevailing in France in 1800. The woman’s costume recalls the fashionable dress of the period, and her pose is similar to those seen in Jacques-Louis David’s portraits, such as Madame Raymond de Verninac. The bared breast underlines the contrast of skin and fabric: in portraits, a convincing rendering of flesh tones was crucial, and in the European tradition, as far back as the sixteenth century, the skin of “Ethiopians”—as Africans were commonly called—was considered especially challenging to paint. Benoist’s work is a striking demonstration of her capabilities as a portraitist.

A respectable woman, however, would have been unlikely to agree to be represented with her breast exposed. The revealing costume of Laville-Leroulx’s black sitter might have recalled, for some viewers, the slave markets in French colonies, where the bodies of black women were inspected by potential buyers. A bared breast was also, however, a motif frequently used in allegories. Elisabeth-Louise Vigée Le Brun, for example, had incorporated a bare breast in her painting Peace Bringing Back Abundance to evoke the generous riches that are the product of political concord. Other viewers, therefore, might have seen Benoist’s figure as an allegory, especially as her costume included the blue, white, and red colors of the tricoleur flag that had been adopted by the French Revolutionary Government in 1789.

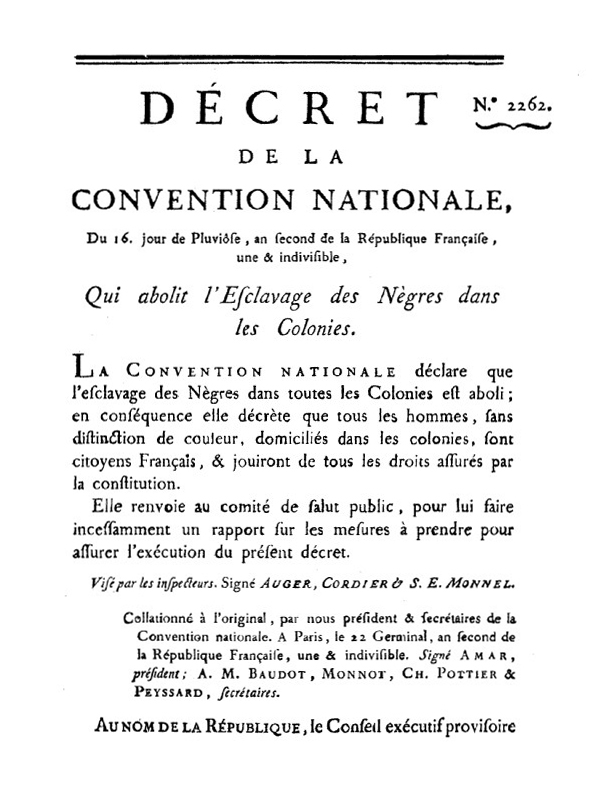

Who was the sitter?

Benoist did not provide her sitter’s name, but it was customary to protect sitters’ privacy by using titles such as “Portrait of a Lady” when exhibiting works at the Salon. In this case we know something of the woman’s status and background, if not her identity. Prior to the Revolution, slavery was not authorized on the French mainland. As early as the fourteenth century, King Louis X had decreed that “France signifies freedom” and that slaves setting foot on French soil should be freed. For this reason, when Thomas Jefferson was appointed ambassador to France from the new United States of America, the two slaves he brought with him—Sarah or “Sally” and James Hemings—were legally free while on French soil. Jefferson paid them a wage during their years in Paris, and when he prepared to return home, they renegotiated their status. Happily, recent scholarship has provided the sitter’s first name, Madeleine.

In 1794, the radical revolutionary government led by the Jacobins and Maxmilien Robespierre extended the domain of liberty by abolishing slavery in French colonies as well as the mainland. French merchants would continue to profit from the slave trade, however, and monarchists in some French territories ignored the regulation, seeking to turn their allegiance to Britain.

Madeleine is thought to have been brought to France from the island of Guadeloupe by the artist’s brother-in-law, a ship’s purser and civil servant. She was likely born a slave in the colony and freed by the decree of 1794, but her actual status may have been ambiguous. Whether she was brought to France as a slave or a servant, she—unlike fashionable women who commissioned their portraits—would have had little influence on how Benoist represented her.

Who was the artist?

We know a good deal more about the artist than the sitter. Marie-Guillemine Laville-Leroulx (Benoist was her married name) was born into a middle-class family. Her father was a civil servant who had failed in business. He believed firmly that his two daughters should be educated to earn their own way—an unusual attitude in the eighteenth century. Marie-Guillemine and her sister first studied painting with Vigée Le Brun and later were among three women whom David took into his studio in the Louvre, challenging concerns about propriety raised by the government minister in charge of the palace.

Laville-Leroulx made her debut at the Salon of 1791, when the revolutionary government opened the exhibition to all artists for the first time. She was ambitious, exhibiting history paintings, which were widely considered beyond women’s capacities. She listed herself as a student of David, even though the artist was a firm supporter of the Revolution, while her family remained loyal to the king. Two years later, she married Pierre Vincent Benoist, who was, like her family, a monarchist. During the Reign of Terror the couple’s life was difficult. By 1800, however, Napoleon I had staged a coup d’etat and installed himself as First Consul of the Directory. With the change in government, Mme Benoist, as she was now known, was ready to take up her public career as an artist.

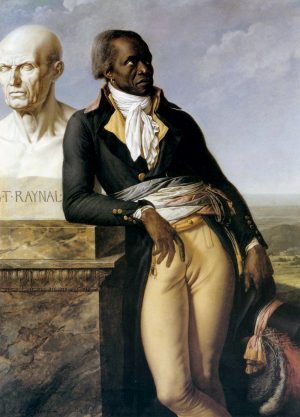

A politically-charged subject

In choosing to paint a woman of color, Benoist selected an unusual subject for a portrait and engaged a politically contentious issue. The only other likeness of an African to be exhibited at the Salon during these years was Anne-Louis Girodet’s Portrait of Citizen Jean-Baptiste Belley, Ex-Representative of the Colonies. Girodet, like Benoist, was a student of David. Belley, who was born in Senegal and enslaved in the French colony of Saint-Domingue, had been freed because of his military service in the French army and was elected one of the colony’s three representatives to the French revolutionary government. Serving from 1793 to 1797, he became well-known as an advocate for racial equality. Girodet’s painting, which juxtaposes Belley’s head with a marble bust of the abolitionist philosopher Guillaume-Thomas Raynal, was understood by visitors to the Salon in 1798 as an argument for emancipation.

Two years later, however, Napoleon I was consolidating his power and began to lay the groundwork for reviving the institution of slavery. He recognized that the Revolutionary government’s decision to free slaves in French territories had not only antagonized citizens of these colonies and other nations, but also had jeopardized the immense profits from the cultivation of sugar that were important to France’s economy. His move was contentious, but it was supported by many who had a vested interest in the economics of slavery, including Benoist’s husband.

The Salon critic who in 1800 dubbed Benoist’s painting a “black stain” was surely influenced by arguments in favor of reinstating slavery. Twenty-first century viewers are more likely to sympathize with the situation of the woman who sat for Benoist. What was Benoist’s purpose in exhibiting Portrait of Madeleine? In conveying the beauty and humanity of her sitter, was she suggesting that this anonymous woman and others of African descent should be free citizens of the French nation? Or was she simply trying to promote her considerable skills as a portraitist in the tradition of David and Girodet? Since Benoist left no statement to explain her work, we can only infer her intentions on the basis of the painting itself and the historical circumstances surrounding its creation.

In 1802 Napoleon reinstated slavery in France’s overseas colonies. Benoist went on to receive commissions for portraits from Napoleon and several members of his family. After Napoleon was defeated, her husband was awarded an important post in the Restoration government of King Louis XVIII. Marie-Guillemine Laville-Leroulx Benoist—much to her dismay—was forced to relinquish her painting career, which was considered inappropriate for a woman of her position in the increasingly conservative political climate.

Additional Resources:

This work at the Musée du Louvre

Mechthild Fend, “Marie-Guillemine Benoist’s Portrait d’une Négresse and the visibility of skin colour,” in Probing the Skin: Cultural Representations of Our Contact Zone, edited by Caroline Rosenthal and Dirk Vanderbeke (Newcastle upon Tyne, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2015).

Mechthild Fend, Fleshing Out Surfaces: Skin in French Art and Medicine, 1650-1850 (Manchester : Manchester University Press, 2017).

Darcy Grimaldo Grigsby, Extremities: Painting Empire in Post-Revolutionary France (London: Yale University Press, 2002).

Janell Hobson, “Portraits of Black Womanhood,” in Black Perspectives, AAIHS, December 14, 2017.

Griselda Pollock, Differencing the Canon: Feminine Desire and the Writing of Art’s Histories (NY: Routledge, 1999).

Viktoria Schmidt-Linsenho, “Who is the subject? Marie-Guilhemine Benoist’s Portrait d’une négresse,” in Slave Portraiture in the Atlantic World, edited by Agnes Lugo-Ortiz and Angela Rosenthal (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013).

James Smalls, “Slavery is a woman: “Race,” Gender, and Visuality in Marie Benoist’s Portrait d’une Negresse (1800),” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 3 (Spring 2004).

Helen Weston, “The Cook, the Thief, his Wife and her Lover: La Ville-Leroulx’s Portrait de Négresse and the signs of Misrecognition,” in Work and the Image I, edited by Valerie Mainz and Griselda Pollock (Aldershot, England: Ashgate, 2000).

Antonio Canova

Antonio Canova, Paolina Borghese as Venus Victorious

by BEN POLLITT

A beauty queen

And the winner of “Miss Arte Italiana” is—drum roll please—Antonio Canova’s Paolina Borghese as Venus Victorious! Or so, at least, is what a recent poll carried out for the Marilena Ferrari Foundation decided.

“Miss Italian Art,” a cringeworthy epithet perhaps, but one which, given the strength of the competition, is nothing to sneeze at—works by Botticelli, Leonardo and Titian were also in contention. Certainly, the semi-nude, life-size portrait of Napoleon’s wayward sister is a sumptuous work of art. Four years in the making, it was commissioned by Paolina’s second husband, the Italian prince, Camillo Borghese, shortly after their marriage in 1804, a union designed to help Napoleon realize his dreams of establishing a pan-European dynasty and legitimize his claims to the Kingdom of Italy.

Canova and Neoclassicism

Anotonio Canova was a leading light of the Neoclassical movement. The style, influenced by the archeological discoveries in Pompeii and Herculaneum as well as the theories of the art historian Johann Wincklemann, looked back to the artistic achievements of the Greeks and Romans with renewed interest, informed by the spirit of rational inquiry that characterized the Age of Enlightenment.

As Inspector General of Antiquities and Fine Art of the Papal States and responsible for acquiring works for the Vatican museums, Canova would have known his Phidias from his Praxiteles. However, he was no slavish imitator. Instead he wished to emulate the works of these earlier artists.

The methods he used demanded absolute precision. Working from numerous preparatory sketches he modeled the form into a life-size clay version. He then cast a plaster model of this which he marked up with points that were transferred on to the marble block. His assistants would carve the marble into shape and only then, for “the last hand,” did Canova raise his chisel, sculpting the form and crucially polishing the marble, using wax, to a fine, glistening finish.

Many of his models were great personalities of the age. Canova would portray them in antique costume. This classicizing of contemporary figures verged sometimes on the ridiculous, as in the colossal nude sculpture of Napoleon as Mars the Peacemaker. His portrait of Paolina Borghese is more successful

A modern day Venus

Paolina is shown reclining on a pillowed couch in a pose of studied grace, both concentrated and relaxed. The modelling of the nude body is extraordinarily lifelike, while Canova’s treatment of the surface of the marble captures the soft texture of skin. The tactile quality of the piece is brought out particularly in the way the sitter’s own hands are occupied, the fingers of her right connecting ever so lightly with the nape of her neck, offer a gesture charged with seductive promise. The head is raised slightly suggesting that something or someone has suddenly entered her line of vision. The apple she holds in her left hand, her fingers wrapped around it suggestive of erotic touch, identifies her as Venus Victorious, the goddess awarded the Golden Apple of Discord in perhaps the first beauty competition in the history of Western culture. The story comes from ancient Greece. Paris the Trojan prince judged Venus more beautiful than either of her rivals, Minerva and Juno. In return Venus introduced him to a Greek girl called Helen and the rest of course is the stuff of epic poetry.

Originally, Canova was to depict her as Diana, the chaste goddess of the moon and the hunt, a role that more would have require her to have been clothed. Paolina insisted on Venus, though. A bit of a loose cannon with a reputation for promiscuity, the Emperor’s sister enjoyed courting controversy and posing naked would certainly have raised a few eyebrows in polite society. But there was more to it than that. Apparently, the Borghese family believed themselves to be descended from the heroic founder of Rome, Aeneas, who according to Virgil was the son of Venus. The choice then not only suited Paolina’s flirtatious character, but also would have been met with approval by the Borghese family, suggesting continuity between the ancient and modern worlds. Her hair, a mass of curls bound in a Psyche knot, serves as a visual connector between the two, being worn in imitation of ancient Greek styles as was the fashion of the day. Its careful articulation offsets the smooth shallow planes of her torso.

Creating a contrast of another sort, the couch Paolina lies on is carved from a different type of marble, the base part of which is covered in rhythmically flowing drapery, much like on a catafalque, a raised platform used to bear coffins. The allusion to mortuary art is not that surprising; in Greek and Roman art the reclining female figure is frequently found on sarcophagus lids. So conspicuous an allusion demands further explanation, though, and I suppose if one were forced to read for a meaning here it would have to be the defeat of death by beauty – as expressed through art – that is being celebrated in the image.

Reception

Canova’s extraordinary capacity to breathe life into his sculptures was noted by his contemporaries. Literally animated, the sculpture would have been on a revolving mechanism, allowing the static viewer to see the work in the round. It would also have been viewed by candlelight. The finely polished waxy surface would have reflected light brilliantly, creating chiaroscuoro, a more painterly than sculptural effect, perhaps, but then Canova was a painterly sculptor. Paolina owes more to the likes of Giorgione’s Sleeping Venus and Titian’s Venus of Urbino and of course David’s Madame Recamier than antique sculpture, a point not lost on the Neoclassical purists of the day who condemned the work as out of keeping with their austere classical theories.

Inevitably the sculpture was going to cause a scandal. While intended for a private audience sophisticated enough to appreciate the classical allusions, given Paolina’s infidelities, the sculpture also served to confirm the rumors about her. If anything, though, Paolina enjoyed the attention. Asked if she minded having to pose nude, she replied: “Why should I? The studio was heated.” Camillo refused to allow the sculpture to leave his residence. Napoleon agreed.

From Ingres to Renoir, from Proudhon to Puvis de Chavannes, Paolina Borghese as Venus Victorious had an enormous impact on nineteenth century French artists. It is in the works of the English sculptor John Gibson, though, who Canova took under his wing later on in life, that we find her most faithful devotee. Animating the figure with pools of reflected light, the glistening waxy surface of his most celebrated work The Tinted Venus owes much to Venus Victorious; together with his own innovative use of polychromy the sculpture provoked outrage among its Victorian audience for whom it appeared a little too real: “a naked, impudent English woman” as one review put her. Canova’s own naked, impudent French woman would have been proud.

Additional resources:

This sculpture at the Galleria Borghese

Antonio Canova, Penitent Magdalene

by BEN POLLITT

A salon sensation

Antonio Canova (1757-1822), the great Neoclassical sculptor, left a truly prodigious body of work, much of it portraiture or mythological in subject matter or, not infrequently, as in Paolina Borghese as Venus Victorix and Napoleon as Mars the Peacemaker, a mixture of the two. Religious works by him are comparatively rare, though, the most celebrated being The Penitent Magdalene. The first version, completed for a private patron between 1794-6, is in the Museo di Sant’Agostino in Genoa, the second, dated 1809, is housed in St. Petersburg’s Hermitage Museum. Heralded as Canova’s greatest work at the time, indeed “the greatest work of modern times” according to the novelist Stendhal, the sculpture obviously struck a chord with contemporary audiences. Though undoubtedly a very moving work of art, a modern viewer might be tempted to ask why such gushing praise?

Commission and Reception

The subject was commissioned by a Venetian churchman, Guiseppi Pruili, presumably for devotional purposes. In 1798 the work was sold and passed into the hands of Giovanni Sommariva, a flamboyant Italian politician who enjoyed a close relationship with Napoleon. Having made the purchase, he converted a room in his Parisian house specifically to accommodate the sculpture, “half chapel, half boudoir, furnished in violet and lit by an alabaster lamp hanging from the cupola,” as one contemporary, Francis Haskell, described it. In 1808, Sommariva had the sculpture exhibited at the Salon in the Musée Napoleon, today’s Louvre, where it created a ‘miraculous’ effect on all who saw it.

A large part of its huge appeal, which bordered on mania, must have been due to the political and religious sensitivities of the time. In terms of the latter, since the Revolution of 1789, France had effectively been a de-christianized state: church land was confiscated, religious images destroyed and tens of thousands of priests forced to abdicate. In 1801, however, Napoleon as First Consul signed a Concordat (an agreement between the Pope and a sovereign state on religious matters), which largely, though not wholly, restored the Catholic Churchs’s pre-Revolution status. That a contemporary religious work by so celebrated a sculptor was being shown in a Salon organized by the French state would have served as a powerful visual reminder of the new role of religion in public affairs.

Just as important, one suspects, is the figure herself, Mary Magdalene mourning the loss of her beloved Jesus. It is a stark and striking image of grief, the painful reality of which in the early 1800’s most households across France were no doubt all too familiar. For decades the country had been at war, first in those turbulent Revolutionary years and then under the leadership of Napoleon, whose military campaigns cost the lives of millions. Having paid such a heavy toll, one imagines that by 1808 the country had had its fill of neoclassical allegories that glamorized war. They knew the true horrors of it well enough and so it is hardly surprising then that Canova’s gentler, more consoling image was met with such enthusiasm.

The legend of Mary Magdalene

A witness to the Entombment and the first to see Christ after the Resurrection, early theologians present Magdalene as the most devout of all of Christ’s followers and an important early Christian leader. In later years, although nowhere in the Bible does it say so, in art and literature she has conventionally been depicted as a repentant prostitute. To atone for her sins, legend has it that after Christ’s death she left the Holy Land and spent thirty years in a desert in Provence, hence the widespread veneration of the saint in France. Canova was obviously well versed in the story, showing Magdalene as a beautiful young woman dressed like a hermit, sitting on a rock and accompanied by the requisite crucifix and skull.

Her downcast, kneeling figure has drawn comparisons with Caravaggio’s Penitent Magdalene, which Canova would have seen in Rome. In both, her kneeling posture emphasises humility, a word originating from the Latin humus or ‘ground.’ The same cradling gesture is also invoked, as though spiritually she is there on Golgotha, cradling the body of Christ as the other Mary is shown cradling her dead Son in the pietà.

Like Caravaggio, also, in the helpless, grief-stricken figure that leans to one side, to the point almost of collapse, we see here not a Classical ideal of beauty but an emotionally and dramatically expressive image, reflecting a highly refined naturalism.

The Hermitage version

The sculpture proved so popular that a copy was commissioned, now in the Hermitage collection. For whatever reason, the gilt bronze cross is missing in this version and perhaps benefits from the omission, the upturned, empty palms evoking both Magdalene’s submission to the will of God and her sense of spiritual abandonment, aware that these hands, the same that had anointed the feet of Christ with perfumed oil, will never touch Him again.

For all its popularity, however, Canova himself thought little of the work, its tumultuous reception in Paris reaffirming his low opinion of French taste, still contaminated in his mind at least by the weak sensuality of the Rococo. A generation earlier, perhaps the greatest of all Rococo sculptors, Étienne-Maurice Falconet, had presented a more fantastical version of the penitent saint in his porcelain Fainting Magdalene who swoons extravagantly into the arms of an angel.

Though Canova’s work is far less cluttered and both formally and psychologically exhibits more restraint, we find a similar hint of eroticism in the depiction of the female form, her garment on the point of slipping down to reveal her breasts, indeed when viewed from behind, has slipped entirely to reveal the round of her back with those thick locks of hair spilling down it. Here that submissiveness noted earlier takes on a sexualized character, which, as with so many celebrated depictions of women at this period, in servicing male fantasies of power, not only reflected but arguably helped maintain those gender inequalities.

Legacy

Whether attributable to the beauty of the thing or to its historical importance, Canova’s Magdalene resonated with the French public for years to come. Three decades on, for instance, we find her interceding for the souls of the damned in Henri Lemaire’s pediment sculpture for the Church of La Madeleine. Distinguished from the ‘saved’ whose bodies are modestly concealed, except for the suckling mother to the far right, Magdalene, kneeling at the foot of Christ, is half undressed, like the ‘damned’ themselves, who are mostly male. The contrast between feminine virtue (clothed) and feminine vice (naked) is all too evident; and so too, perhaps, the Madonna/Whore complex that underpins the image, a psychological condition in which men perceive women as either madonnas to be protected or whores to be punished, a somewhat hellish situation as Freud explained, “Where such men love they have no desire and where they desire they cannot love”. The prevalence of this unfortunate habit of mind might also account, to some extent at least, for the popularity of Canova’s work in the early nineteenth century and, indeed, for our continued fascination with Magdalene herself.

Vignon, Church of La Madeleine

by BEN POLLITT

Background

The Place de la Madeleine had been consecrated as a site devoted to Mary Magdalene in 1182. During the period known as the First Republic (1792-1804), following the French Revolution, the foundations of earlier sacred buildings were removed and discussions were had as to what to do with the space. As France had been de-Christianized during the Revolution a civic rather than a religious function for the building was decided upon; various suggestions were put forward including a new site for the Bank of France.

Considerations were brought to a halt, however, when in 1804 Napoleon crowned himself Emperor. What followed was one of the most ambitious propaganda programs of the nineteenth century. As well as looting works from the world’s finest collections to display in the newly refurbished Louvre, renamed the Musée Napoleon, some of the greatest artists and sculptors of the age were recruited to exalt the new emperor. It was only fitting that Napoleon would turn to architects, too, to realize his vision of an imperial capital city. Three monuments of particular note were constructed with this end in view: the Arc de Triomphe, the Vendôme Column and the church at the Place de la Madeleine.

It was never Napoleon’s intention to build a church for Mary Magdalene, though. For him the new building would stand as a Temple to the Glory of the Army, and by that, of course, he meant his own imperial army, that well-organized band of marauders who, having defeated the Austrians in the Battle of Austerlitz in 1805, had managed to supplicate a great swathe of Europe. To celebrate their achievement, a competition to select the best design for the Temple was established in 1806 to be judged by to a jury selected from the Imperial Academy. As it turned out, the jury proved academic in more ways than one, their opinions counting for little as, despite their disapproval, Napoleon opted for the designs of one Pierre-Alexandre Vignon (1763-1828).

Vignon, who had trained under the great Neoclassical architect Claude Ledoux, envisioned a peripteral temple (a temple surrounded by a single row of columns). Lacking Ledoux’s more visionary character, however, Vignon’s design for the exterior was basically a scaled up version of the Maison Carrée in Nîmes.

The exterior

Unlike the Maison Carrée though, the portico of La Madeleine has eight columns rather than six. These fluted Roman Corinthian columns – there are fifty-two of them in all – rise up to a staggering twenty meters and encompass the entire structure. The entablature they support is embellished with a bipartite architrave surmounted by a frieze with a decoration of garlands and putti.

While not quite so ornate, the features, in the main, reproduce those found on the Roman temple. The dentils, those repeated teeth-like blocks that ornament the cornice, seem bulkier, however, lending the façade a somewhat more austere character.

While the exterior bears the hallmarks of Napoleonic propaganda, evoking the grandeur of Imperial Rome, after his fall, the Bourbon Restoration (1814-30) sought to revive the relationship between church and state. For this reason it was decided, as the temple was still incomplete, to return to the pre-Revolution purpose of the building project, namely to construct a church dedicated to Mary Magdalene.

The pediment frieze

In contrast to the Napoleonic design of the temple, the pediment frieze, designed by Philippe Joseph Henri Lemaire in 1829, is a masterpiece of Bourbon Restoration propaganda. The subject is The Last Judgment, a centuries-old motif found on relief sculptures above the doors of countless churches and cathedrals. While Lemaire largely follows iconographical convention, depicting Christ the Judge at the center of the composition and on His right the archangel Gabriel with his horn announcing the Day of Judgment and on His left the archangel Michael wielding the sword of justice, it is in the figure of Mary Magdalene kneeling at the foot of Christ that the underlying message of the sculpture is revealed.

Mary Magdalene has very strong connections with France. According to tradition she was among the first Christian proselytizers: after the crucifixion she journeyed to Provence from the Holy Land converting the French to Christianity. She is also, of course—albeit wrongly—often portrayed in art and in literature as a repentant prostitute, as indeed she is here; notice, for example the contrast between the virtuous female figures to the right whose bodies are concealed and her own state of semi-nakedness.

As well as a straightforward Last Judgment, the inclusion of the repentant Magdalene figure has led some to read the frieze as a political allegory in which the damned stand for those who had been involved in the Revolution and who, in the eyes of the restored monarchist regime, were effectively traitors. Given that such a large portion of the French people fell into this category, rather than condemn and punish them, they were called upon to repent of their sins, as Magdalene had done, before being embraced back into the arms of the ruling establishment.

Unlike in England or America say, where public building programs such as the British Museum or the Capitol exhibit a single-minded confidence, state architecture in France at this period reflects the country’s complex and conflicted political landscape, made up of republicans who had fought for the Revolution, of imperialists who had followed Napoleon and of monarchists who were loyal to the king. The unsettled look and feel of La Madeleine is a prime example of this tendency, particularly so in the striking contrast between the outside of the building and its interior.

Interior

On entering the church we are faced with a surprisingly opulent spectacle, especially given the severity of its exterior. Standing in the narthex (porch) of the church, we look up to see a coffered barrel vault, lavishly gilded like the rest of the interior. Above the door is the famous pipe organ on which such composers as Camille Saint-Saëns and Gabriel Fauré played.

Turning around and walking down the long nave, one passes under three large domes, supported by pendentives (triangular sections of vaulting between the rim of a dome and the arches that support it), decorated with colossal relief figures. Each dome is coffered and has a glazed oculus allowing in light, features that obviously recall the Pantheon.

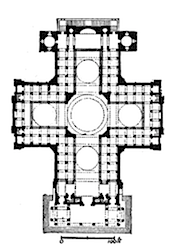

Three pairs of wide bays are thus created, each with pedimented niches supported by ionic columns that serve to form side altars. Far from the classical temple type the exterior would lead us to expect, architectural historians have compared the interior of the church to that of Roman baths; the triple cross-vaults of the Baths of Caracalla, for instance, may well have been in Vignon’s mind when designing those domes.

At the north end is the semi-dome of the apse, under which sits the altar and behind it a wonderfully theatrical statue by Carlo Marochetti of Magdalene being lifted up by angels, a fine example of Romantic sculpture.

Above it, in the cupola of the choir, is Ziegler’s mural entitled The History of Christianity, showing Magdalene ascending into heaven borne by three angels.

Beneath her is Napoleon in his coronation robes, positioned center stage, his figure directly aligned with Christ’s. Facing him is Pope Pius VII, with whom he signed the Concordat of 1801, a document which reestablished the authority of the Catholic church in France after the Revolution and which is alluded to on the scroll the cardinal who stands behind Napoleon carries in his left hand.

It is a curious painting, completed during the July Monarchy (1830-48) when the liberal king, Louis-Philippe, struggled to reconcile those contending political factions. That Napoleon had in fact a very low opinion of the church and sought to limit its powers in France is, of course, neither here nor there.

In this world the revolutionaries, like Magdalene, have repented, Napoleon is shown to have saved the day and the church and by association the Catholic monarchy are restored to their rightful place in the natural order of things. Sadly, for Louis-Philippe, it is a wildly optimistic reimagining of history, one that in the end – as the violent events of 1848, the Year of Revolutions, demonstrated – would prove ill founded.

Additional resources:

Soufflot, The Panthéon (Church of Ste-Geneviève), Paris

by DR. PAUL A. RANOGAJEC

An imposing portico and dome

As you leave the Luxembourg Gardens and head east along the Rue Soufflot in Paris’s dense Latin Quarter, the imposing portico and dome of the Panthéon draws you forward. It is an irresistible sight. One of the most impressive buildings of the Neoclassical period, the Panthéon, originally built as the Church of Ste-Geneviève, was conceived as a monument to Paris and the French nation as much as it was the church of Paris’s patron saint.

Jacques-Germain Soufflot, its architect, was highly praised for the design—although a few of his contemporaries thought he went too far in defying tradition and structural necessity. Soufflot was heralded during his life as the restorer of greatness in French architecture and the building was lauded, even before it was completed, as one of the finest in the country.

Encountering it today as its lofty dome rises far above surrounding buildings—including two of its most important neighbors: the small but influential Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève (1838-50) by Henri Labrouste, and the enchanting late-medieval and Renaissance church of St-Étienne-du-Mont (both, above)—it remains as awe-inspiring as it must have been in the late eighteenth century, despite some important changes since its opening. A century and a half of French political history can be tracked with unusual precision in the original design and subsequent changes in the Panthéon’s function and title.

150 years of French history

Soufflot’s Ste-Geneviève was built to replace a decrepit medieval abbey, an idea first proposed during the time of King Louis XIV. The project fit, however, with Louis XV’s program to aggressively promote his role as avatar of the nation’s greatness. The king saw the church’s rebuilding as a token of his munificence and as material confirmation of the French Catholic Church’s quasi-independence from the pope. And more specifically, the church was the fulfillment of Louis XV’s pious vow, made in 1744 to his mistress, Madame de Pompadour, to rebuild the church if he recovered from a fever and illness so severe that he had been administered the Last Rites (a Catholic ritual of prayer for those considered close to death). Soufflot’s Ste-Geneviève, then, was meant to focus the nation’s piety on an unmistakable symbol of national and royal significance.

The church’s dedication to Saint Genevieve was important to its original political significance. She had become one of France’s most important historical religious figures well before the eighteenth century. According to legend, she had been instrumental in repelling Attila’s Huns before they reached Paris in 451, and her relics were said to have miraculously helped Odo, the ruler of Paris, resist a Viking attack in 885. A monastery was eventually formed around the site of her burial in a church built originally in the early sixth century by Clovis, the first king of the French territory, although it underwent many changes through the twelfth century. The site, then, was the spot of an ancient and venerable shrine—and vitally important to the identity of Paris through many centuries.

The purity of Greek architecture and the daring of Gothic

Thanks to the Marquis de Marigny, the Director of Royal Buildings, Louis XV appointed Soufflot architect of the new church in 1755. By that time, Soufflot had achieved high standing in the French architectural profession, having recently completed a number of important buildings in Lyon, France, as the city’s municipal architect. Soufflot had earlier established close ties to the French court when he accompanied Marigny as an architectural tutor on a journey through Italy. Marigny and the king calculated that Soufflot was the best candidate to give them the kind of memorable and forward-looking building that they wanted for their interconnected political and religious purposes.

Soufflot’s pupil Maximilien Brébion stated that the church’s design was meant “to unite … the purity and magnificence of Greek architecture with the lightness and daring of Gothic construction.” He was referring to the way in which its classical forms, such as the tall Corinthian columns and the dome, were joined with a Gothic type of structure that included the use of concealed flying buttresses and relatively light stone vaulting.