8.3: Representing War

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

The Civil War (1861- 65) interrupted all this. It brought the fantasy of nurturance and social accommodation to a crashing halt. Frederic Church's Cotopaxi, 1862, was painted in the same year that Union and Confederate troops pulverized each other in the Battle of Antietam, the bloodiest twenty-four hours of the entire Civil War (fig. 8.29). Church abandons the environmental harmonies that unified Heart of the Andes and substitutes in their place a vision of nature torn and divided. An Ecuadorian volcano erupts at the left, its smoke almost blotting out the sun that competes with it for dominance of the heavens on the right. The division between volcano and sun is reinforced by the canyon in the foreground, ripping the composition along its central axis. Church's Humboldtian world has exploded into competing realms tinged with blood-like reds. If Church still intends his viewers to believe they are pilgrims, their destination is now the apocalypse.

A similar drama grips Martin Johnson Heade's (1819-1904) Thunderstorm Over Narragansett Bay, 1868, painted in the immediate aftermath of the War (fig. 8.30 and p. 240). Heade fills the quiescent air of luminist painting with blackness and a dramatic bolt of lightning. The glass-like surface of the water has become as dark as the foreboding sky; the sails of the small boats in the bay droop in the airless atmosphere; and the miniature men returning from their excursions look like puppets rather than Jacksonian adventurers. Only the hovering gulls, white in contrast with the surrounding darkness, offer any sign of escape. And their winged destination, above the men and between the two moored boats, is uncertain: are they harbingers of hope or signals of distress? Heade's electrically charged atmosphere, where dark surfaces bristle with apocalyptic energies, marks one painter's farewell to the peace and serenity of former times.

Even Eastman Johnson's (1824-1906) Negro Life at the South, painted in 1859, two years before the bombing of Fort Sumter and the eruption of war, demonstrates how a scene of everyday black life, filtered through the prism of the minstrel show, carries disruptive possibilities directly beneath its calm surface (fig. 8.31). The frieze of figures across the lower portion of the canvas is a virtual catalogue of slave characters: the boy at the center of the composition, who pauses wistfully to listen to the banjo player (a familiar stereotype from minstrel shows); the exotic young mulatto who coyly cocks her head in response to the suitor who leans toward her; and the dark woman at right of centerprobably a slave of West Indian descent-who watches a young boy dancing. Johnson's picturesque treatment has led many to read this painting as an apology for "the peculiar institution," as slavery has been called. Yet he subtly undercuts stereotypes: the banjo player leans back with a melancholy expression, resisting the role of minstrel entertainer. Each figure seems oddly static, as if lost in thought, or deliberately indifferent to the entrance of the white mistress on the right. Johnson's "behind-the-scenes" look at slavery seems staged, as if the main figures are biding their time until their need to perform before white observers is over. The decaying overhang at the rear of the housealong with the rundown condition of the yard-hints at the demise of slavery in the near future . Following disputes about the location of the scene, the scholar John Davis has established that the painting was done literally in the artist's backyard, in the notorious alleyways of Washington, D.C., Johnson's home. His behind-the-scenes glimpse thus reveals the hollowness of Northern claims about black freedom. At the very edge of the Mason-Dixon Line, black life is still staged as a minstrel show. Johnson's behind-the-scenes glimpse reveals the existence of slavery in the heart of the nation's capital, hidden from view. His act of exposing slavery provided yet another voice in the clamor that led to war.

As these three different paintings suggest, the challenge facing artists and photographers of the Civil War was twofold: how to capture the chaotic reality of war and the social issues behind it while still suggesting a larger order and purpose to the struggle. The Civil War has been characterized by historians as the first modern war. With over 600,000 casualties, it introduced mechanized weaponry, trench warfare, and corporate forms of organization. The historian Eric Foner has noted an unexpected irony to the Civil War. It ended the way of life that Lincoln had fought to preserve: the world of the independent artisan-entrepreneur. The victory of the North was a victory for modernization: the centralizing of state power; the rapid spread of industry; the mechanization of labor; the rise of large bureaucracies; the emergence of national corporations; and the uninhibited expansion of the North's capitalist economy.

Though artists could not tell this story directly-paintings, after all, are not inventories of battles-they could provide images that explored both the causes and the consequences of war. In the sections that follow, we focus primarily-but not exclusively-on photography. The invention of photography precedes the onset of the Civil War, and the photograph developed into the medium par excellence for telling the story of that war. The photograph's sobering combination of black and white tones, together with its blunt air of truthfulness, left the public hungry for, as well as horrified at, the vision of war that emerged from the photographer's lens.

But in order to understand Civil War photography, we need to backtrack briefly to the invention and early history of photography itself.

Daguerreotypes and Early Photography

Photography was the "new kid on the block" in the antebellum era. Invented in France and England, and first launched in 1839, this technological form of image-making astonished its early audiences. Samuel F. B. Morse, a skilled painter and inventor of the telegraph, observed the work of Louis-Jacques Daguerre in Paris and wrote that the images were "Rembrandt perfected." Morse explained that the "minuteness" of detail in a daguerreotype resembled the use of a "telescope in nature" (fig. 8.32).

American responses to photography veered between a love of magic and a desire for mimesis. Nineteenth-century audiences viewed the daguerreotype as nature's own self-portrait: the way that "nature paints herself." The lack of handwork-the absence of brushstrokes or engraver's marks-was thought to guarantee the "objectivity" of the image. Photography represented the height of realism, the dream of artists from the Renaissance onward to produce the illusion of a real world on a flat surface. But photography was no illusion. As its name suggests, the photograph was "writing with light." Photographs were thought to reveal the truth of nature without the distortions of human intervention. A prominent merchant, explaining to others how his daguerreotype was made, said simply that you "sat and looked at the glass" lens until you "grinned yourself on the plate."8

Very soon after its introduction, photography led to a virtual industry of new patents and technologies. Some of these innovations were designed to improve the quality of the image, while others focused instead on photography's commercial applications. In the countryside, itinerant artists converted from painting portraits to making photographs, and were joined by other craftsmen who wished to take advantage of the new technology: blacksmiths, shoemakers, apothecaries, artisans, and enterprising inventors. These rural "image-mongers" tended to work individually, moving from door to door and town to town with daguerreotypes of varying quality In the cities, to the contrary, daguerreotypists sought to appeal to a more cultured clientele. They advertised themselves as professionals, touted the aesthetic quality of their work, and set up shops that employed assistants and helpers. Daguerreotypes became so popular that by the early 1850s there were "daguerreotype factories" across the urban centers of the United States. Each offered low prices, standardized packages (poses, mats, cases), familiar props, and speedy delivery.

By the end of the 1850s, the daguerreotype had given way to a new photographic technology, the wet-plate process. Unlike daguerreotypes, which produced a single, non-reproducible image on a plate coated with reflective silver (there was no negative), the wet-plate photograph allowed unlimited paper prints to be made from a single exposure. By allowing for multiple prints, it helped answer the almost insatiable demand among all classes for photographs of family and friends.

If photography satisfied the need of the Victorian family for images of itself, it also answered a larger social anxiety. Photography provided a society undergoing rapid urbanization with a way to affirm the importance of "character." Photographers advertised their ability to bring out the truth of their sitters: to capture a person's essence in a single image. The photograph revealed not just an enduring likeness, but a true expression of the sitter's personality.

As cultural historians Alan Trachtenberg and Karen Halttunen have pointed out, antebellum urban America suffered from a "crisis of social confidence." As cities swelled in size, people feared their inability to "read" the true motives and designs of the strangers they encountered. Photographers seized on this anxiety by creating a visual product that allowed the viewer to "discern inner character from outer appearance." Daguerreotypists- and later wetplate photographers-created a standardized set of poses and expressions designed to reveal the "inner character" of their sitters. This process helped reassure a middle class concerned about modernization that they were still able to discern truth from falsity, good from bad. In this regard, photography performed a cultural role similar to that of genre painting. Both media provided people with a vocabulary of familiar characters and types that allowed them to navigate their daily lives with confidence. What you saw was what you got.

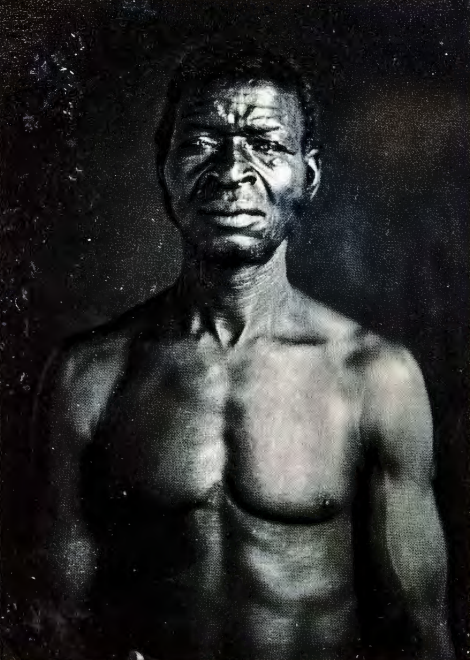

PHOTOGRAPHIC DOCUMENTS OF SLAVERY. At the same time that daguerreotypes were marketed as family keepsakes, they were also enlisted in the service of such pseudosciences as phrenology and physiognomy. Practitioners of these and other popular movements claimed to be able to read human character from the shape of the head and the configuration of the body. With the aid of the camera, they sought to create an "objective" visual record that distinguished the normal from the abnormal. Photographs were used to document criminals, immigrants, and slaves. By the end of the century, photography had developed into an essential tool of the police and government in monitoring the population and tracking social "deviance."

In 1850, the Harvard professor Louis Agassiz, perhaps the most famous geologist and scientist in America, commissioned]. T. Zealy, a daguerreotypist in Columbia, South Carolina, to take a series of photographs of slaves from nearby plantations. The goal of the series was to provide evidence for the theory that Africans were not direct descendants of Adam and Eve but products of a separate, "second" creation. The doctrine of "separate creation" was intended to justify white racism and slavery. Zealy photographed African-born slaves whom he regarded as specimens or "types" (fig. 8.33). The portraits he sent to Agassiz stand today as perhaps the most haunting and painful images to emerge from the era of the daguerreotype. They show naked or partially clothed figures facing the camera head-on. They also reveal whip-marks, scars, and other disfigurations from slavery: What rage, pain, humiliation, or resistance the making of the daguerreotypes provoked among the sitters goes unrecorded. We are left instead with their stares, stoic and impassive, masking worlds of feeling that the viewer can only imagine.

MATHEW BRADY AND HIS "GALLERY OF ILLUSTRIOUS AMERICANS." Nowhere was this appeal to the "truthtelling" characteristics of the daguerreotype more evident than in the emergence of photographic galleries devoted to images of public figures. Mathew Brady ( c. 1823-96), known today primarily for his daguerreotypes of the Civil War, was famous among his contemporaries for an exhibition space in New York filled with portraits in this medium of celebrated citizens, civic leaders, politicians, artists, and renowned visitors. Begun originally as a portrait studio in 1844, the gallery moved many times as it grew more popular, relocating always to a more fashionable address. Brady saw himself as a chronicler of public history. He viewed his work as part of his "obligation to my country to preserve the faces of its historic men and mothers."

Brady invited the notable figures of his day to pose for him. Their photographic portraits were then displayed in the gallery as both a public service and a keen method of self-promotion. Brady referred to his collection as his "Gallery of Illustrious Americans." He published engravings of his daguerreotypes in book form and in popular magazines of the day. Like P. T. Barnum, whose famous American Museum mingled high-minded exhibits with curiosities and oddities, Brady drew a steady flow of visitors to his gallery by highlighting its civic appeal. Visitors could study the likenesses of public figures and discover their inner "character," the sources of their greatness. Such discoveries would lead not only to appreciation but emulation. Viewers of Brady's gallery would be educated in their civic responsibilities and inspired to continue in the footsteps of those they beheld (fig. 8.34).

The irony of Brady's gallery is that it was organized more like a modern factory than an institution for civic advancement. Brady employed a vast array of workers who managed the gallery, greeted visitors, and produced photographs of those who desired to have their portraits taken. The work was divided into specialized tasks. Brady, whose eyesight was failing by the 1850s, rarely took his own pictures. His role instead resembled that of manager and foreman. He oversaw the whole, ensuring that any portrait that carried his brand name, "Brady of Broadway," measured up to the highest standards. As Alan Trachtenberg notes, a Brady portrait bestowed "instant recognition and prestige."9

The Photographic Image and the Civil War

With the advent of the Civil War, Brady hired as many as twenty teams of photographers to record the unfolding tragedy. Though he spent most of the war years managing his various teams, he also traveled to several important battle sites. Unusually for him at this point, Brady personally photographed scenes from Bull Run, Antietam, Fredericksburg, and Gettysburg. He displayed his photographs from the war, as he had earlier displayed his portraits of notable people, in his New York gallery. Visitors viewed the images "with the aid of a magnifying glass," seeking to discover the individual features of the dead. Like visitors to the Vietnam Memorial in Washington, D.C., a century later, viewers at Brady's gallery approached his photographs as almost talismanic reminders, through the powers of art, of lives lost and now mourned.

The heroism of war, however, was gone. Or at least it was impossible to capture with photographic equipment that required hours of preparation, long exposure times, and vast amounts of labor. Because photographers could not record the travails of battle itself, they turned instead to the mundane details of the 'before" and "after": life in the camps before battles, and scenes from the field after them. What they presented was not war, but the peripheries and vestiges of battle. The camera recorded disheveled, disenchanted, and bored men; it paused over scenes of daily life in army camps and hospitals; and it lingered in the fields in the hours and days after battle. There it captured the litter of dead bodies and devastated landscapes.

IMAGES OF THE FALLEN. A photograph by Thomas C. Roche (died 1895), A Dead Confederate Soldier, Petersburg, Virginia, of 1865, conveys the anonymity of war (fig. 8.35). The pine trunk in the foreground serves as a visual barrier, separating the viewer from the dead soldier. The tree's cropped position adds a note of arbitrariness to the image, undermining the photograph's square format with its oddly angled placement. The emptiness of the space-the barrenness of the ground, the lack of vegetation- isolates the soldier visually and depersonalizes the scene surrounding him. The photograph shocks the viewer at the same time as it undermines any effort on the viewer's part to heroicize the soldier's death. The viewer encounters instead sheer corporeality: the body damaged and lifeless.

No wonder then that what is perhaps the most famous photograph of the Civil War, Timothy O'Sullivan's (c. 1840-82) A Harvest of Death, Gettysburg, July, 1863, counters its vision of decay and anonymity with a hint of mystery (fig. 8.36). The photograph's propensity for realism dissolves as the eye travels from foreground to background. The ghostly figures in the distant haze appear like versions of the Grim Reaper. The very title of O'Sullivan's photograph, A Harvest of Death, adds an almost biblical dimension to the scene. The photograph seems to implore its viewer to step imaginatively over the wall of bodies in the foreground. What follows is a recession into deep space. The farther we travel toward the horizon, the more the battlefield and bodies seem to dematerialize. O'Sullivan's photograph leaves open the question of whether the light in the background represents hope or emptiness.

Another Gettysburg image, Alexander Gardner's (1821-82) Home of a Rebel Sharpshooter, Gettysburg, 1863, refuses any suggestion of hope (fig. 8.37). The dead Confederate soldier in the foreground blends in with the rocks that surround him. He seems already one with the inanimate world. His rifle leans against a pile of boulders that once formed a wall to hide and protect him. That wall serves no purpose now. In contrast to the sweep of open space that distinguishes The Harvest of Death, the perspective in Home of a Rebel Sharpshooter is entirely blocked. The viewer is hemmed into the shallow foreground and possesses no visual pathway to the background. The photograph's unforgiving realism-its allegiance to death and decay-leaves little room for transcendence. Years after the photograph was taken, the image was discovered to have been posed. Gardner and his assistants carried the body to the spot where it was photographed, and added the rifle.

This staging of an image that seems so immediate and real testifies to the pressure that photographers felt to make meaning of otherwise senseless events. By placing the soldier in the ravine behind a barrier of rocks, Gardner created an implicit narrative of spying and danger. That narrative, in turn, lends dignity to the life of the fallen soldier.

Photographers like Gardner had three barriers to overcome during the Civil War: they needed to master the slowness and complexity of their own instruments; they needed to transform the randomness of what they saw into moments of significance; and they needed to counteract the unflattering realism of the photographic image itself, which tended to highlight the physical and bodily aspects of war at the expense of its heroism. Gardner's Home of a Rebel Sharpshooter copes dramatically with all three concerns.

We might contrast Gardner's bleak image of a Confederate sharpshooter with an engraving produced the previous year by Winslow Homer (1836-1910), a young Boston-born artist who spent the war years illustrating soldiers' lives for Harper's Weekly. Magazines of this kind lacked the technology to reproduce photographs. They had to rely instead on artists and illustrators for a steady stream of images. In The Army of the Potomac-A Sharpshooter on Picket Duty, 1862, Homer captures the delicate balance of a Union sharpshooter perched in a tall pine tree (fig. 8.38). The diagonals of the tree's limbs, the soldier's feet and the rifle lend the image an off-balanced perspective. The soldier counters the tilt of the tree with his left hand and foot, each braced against the tree as he steadies the rifle . The canteen hanging from the limb on the right hints at the long duration of his "picket duty." He has probably sat in one position for hours. The soldier's mastery of his situation- his ability to balance himself against the odds- contrasts sharply with the sprawled and defeated form of Gardner's sharpshooter.

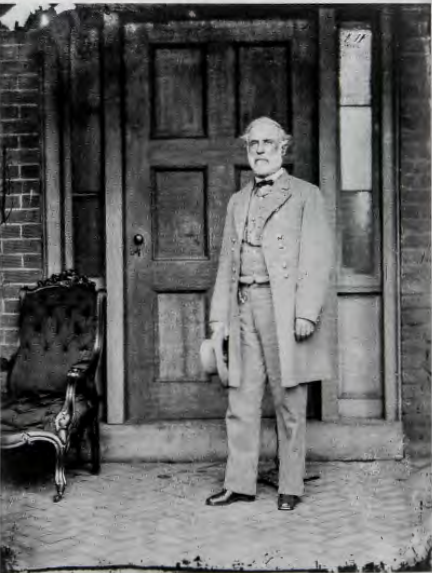

War and Peace

For all the efforts of artists to transmit images from the front as rapidly as possible, no photographer was present at Appomattox Court House at the conclusion of the Civil War. Instead, Mathew Brady took a portrait of General Lee shortly after his surrender (fig. 8.39). The image shows Lee standing in front of his Richmond home wearing his gray Confederate uniform one last time. Lee had to be persuaded by his wife to venture outside the house and pose for Brady, whom he had met before the war. Brady portrays Lee as a figure of dignity and honor. The large upholstered chair to the left, coupled with the visually prominent door and doorknob, transform Lee into a latter-day Cincinnatus, the Roman general who preferred privacy and retirement to war. By capturing Lee in a domestic context, Brady anticipates the homecoming awaiting soldiers of both sides at the end of the war. His photograph gestures in the direction of national reconciliation and a return to normalcy.

PRISONERS FROM THE FRONT BY WINSLOW HOMER. Brady's emphasis on reconciliation has echoes in the post-war painting of Winslow Homer. For Homer, the end of the war meant the beginning of a new era. In Prisoners from the Front, 1866, Homer pits a Union officer against three disarmed Confederate prisoners, their standard-issue rifles tossed upon the ground before them (fig. 8.40 ). Four years of fratricidal strife are reduced in Homer's painting to the spatial and psychological gulf that separates the victor from the vanquished. The power of Homer's painting lies in the dignity displayed by each of its main characters. Homer's Union officer refuses to lord it over his prisoners; instead, he regards them respectfully. Their heads, like his, just puncture the horizon line. In this way, they share with him a capacity to rise above nature and transcend their recent histories. Though the painting's four protagonists still need to resolve their fraught relations, they give promise, by their postures and calm demeanors, of a future defined by respect and reconciliation. For a painting completed only one year after the war's end, Prisoners from the Front demonstrates a sense of compassion very different from the postwar bitterness expressed by many of Homer's peers.

The painting also reveals the influence of photography on Homer's work. Early cameras tended to wash out the sky and background of outdoor scenes. Homer clusters the soldiers in the foreground, close to the picture plane, and empties the background of detail, repeating in his painting ways of seeing made popular by the camera. In the process he foregoes the middle-ground landscape of the Hudson River School, with its language of progress and optimism. Instead, Homer converts the two-dimensional and voided spaces of landscape photography into a new style of painting: psychologically acute, empirically driven, and reticent about any promise of transcendence.

TWO VERSIONS OF THE HOME FRONT. While Homer converted the image of captured soldiers into a meditation on the possibility of national reconciliation, other artists focused on the role of domestic life in the healing of the nation. Lilly Martin Spencer (1822-1902), whom we have already encountered as an antebellum sentimental artist (see fig. 6.1), engaged post-war history in her own way. In War Spirit at Home (fig. 8.41), Martin shows a Northern mother reading a freshly unfolded New York Times with news of the 1863 Union victory at Vicksburg. Three of her four children parade around the family table, merrily imitating the victorious troops. It is a humorous, anecdotal scene, and yet, for all that, the painting also argues for the role of women in shaping domestic life, transmitting, through their children, the values for which the war was fought. By allying the woman with the New York Times, Spencer links her heroine to the larger public sphere. She also suggests that women bear responsibility- like the popular media of the day-for maintaining and preserving knowledge of the past. Painted in 1866, one year after the conclusion of the war, War Spirit at Home fires its own preliminary shot in the post-war battle over the war's memory.

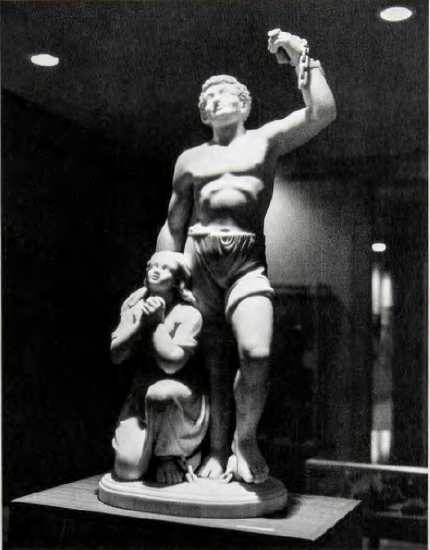

Edmonia Lewis (b. 1845), a sculptor we have already encountered (see fig. 6.3), creates a very different image of the work of the family in the rehabilitation of post-war society. Lewis, of mixed Native and African American heritage, turns to the family to safeguard the rights of newly freed African Americans. Her most famous work, Forever Free, 1867, depicts two former slaves, male and female , at the moment of their emancipation (fig. 8.42). Standing in a classical contrapposto pose, the man rests his weight on one straight leg while bending the other, as if about to vault forward into the promise of the future . His left hand raises his severed shackles skyward in a gesture at once thankful and exultant. The clasp of the manacle still binds his arm, though the chain has been broken. His right arm rests protectively on the shoulder of the woman, presumably his wife, who kneels beside him. His muscular torso calls attention to his strength and dignity, while his curly hair suggests his African ancestry as well as a resemblance to classical statuary.

The woman, on other hand, shows no signs of African heritage. Both her hair and her facial features are entirely classical. The scholar Kirsten Buick interprets the contrast between the two figures-one visually identified as African American, the other not-as part of Lewis's desire to universalize and idealize her women. By depicting the woman in neoclassical terms, Lewis was, in effect, indicating how she herself wanted to be viewed: as neither a "carrier of property," nor a "racist stereotype; ' but a free woman.10

How then do we explain the kneeling woman's subordinate position relative to the man? The answer lies in the politics of black advancement in the years following the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863. Abolitionists had long criticized slavery for the destructive effects of separating parents from children and husbands from wives. Lewis's sculpture converts that criticism into a post-Emancipation challenge. The task facing African Americans after slavery was to reestablish the family. According to the values that prevailed at the time, the husband acted paternally to protect those in his care, while his wife professed sentimental values: "submission, piety, and virtue." Forever Free wishes to advance the cause of African American freedom by portraying a strong, if traditional, family as the first step toward independence. Lewis's goal was not parity between the sexes, but equality among the races.