8.2: The Sublime- The Formation and Development of the Hudson River School of Painting

- Page ID

- 232315

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)In the same years that Downing helped popularize the picturesque landscape, and Greenough converted nature into a lesson in practical design, artists and entrepreneurs were discovering the commercial possibilities of sublime prospects and mountain vistas. In 1824, a small tourist hotel opened in the Catskill Mountains near Kaaterskill Falls, New York. Situated high upon a rocky ledge with breathtaking views of the nearby ridges and valleys, the Catskill Mountain House provided its visitors with an opportunity to experience the wilderness from the comfort of a private room. Visitors to the Catskill Mountain House were awakened each morning by a hotel employee, who would arouse them just in time to catch the rising sun. They would spend the rest of the day exploring the nearby woods, visiting Kaaterskill Falls, or awaiting the late-afternoon thunderstorms that often raged in the valley below. Their experiences mark the beginning of a national love affair with the wilderness, an affair all the more popular for being consummated from the safety of a hotel balcony.

Edmund Burke had insisted that terror by itself was not sublime (see page 243). The sublime required an assurance of safety: powerful forces viewed from a distance. The Catskill Mountain House provided tourists with a way of testing Burke's statement.

The Practice of Landscape Appreciation

The first guests at the Catskill Mountain House tended to be elite or middle-class travelers from Boston, New York, and the urban centers of the northeast. They arrived at the mountain as one leg of a larger "pilgrimage" that frequently included Niagara Falls and the springs at Saratoga. Their goal included more than relief from the summer heat, or a quest for novel experiences. They sought a first-hand encounter with the spiritual possibilities of the landscape. The way had been paved for them, metaphorically speaking, by an outpouring of prints, travel books, and pamphlets in the 1820s and 1830s extolling the pleasures of landscape viewing. With the help of these guidebooks, visitors to the Catskill Mountain House saw themselves less as travelers than as "pilgrims," finding in the vistas before them a glimpse into "divine" truth. Upon reaching the summit, one traveler noted that he immediately "leaned upon my staff," gazed out at the "omnipotent picture" before him, and "looked abroad upon its God-written magnitude." The language reveals the traveler's reliance on contemporary travel literature, which frequently described the landscape as sacred space. The "staff," a necessary prop for any would-be pilgrim, appeared in countless images of mountain visitors.4

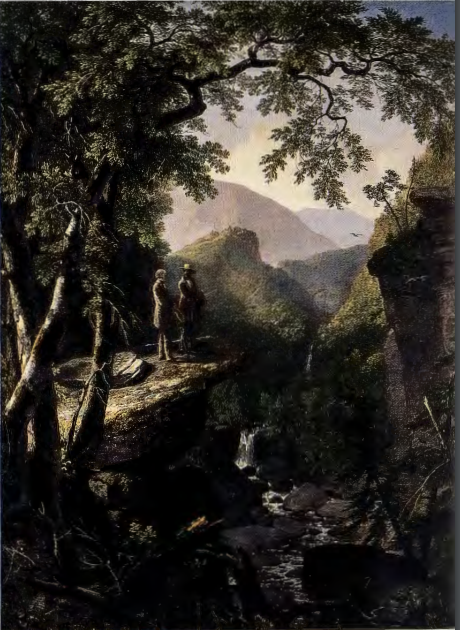

CATSKILL MOUNTAIN-HOUSE. This print from 1830 depicts a group of genteel travelers climbing South Mountain en route to the hotel (fig. 8.15). The vertical format of the print highlights the sense of ascent, suggesting that the hotel represents not only a physical but a spiritual endpoint to a morally edifying journey. As scholar Kenneth Myers points out, the focus in the image on the travelers themselves, rather than on the vista that they view, draws our attention to "the practice of landscape appreciation itself." 5 Three figures point off to the distance; their gesture underscores the act of instruction. They teach their fellow travelers how to see, offering their companions-as well as the viewer of the print-an edifying lesson in landscape appreciation.

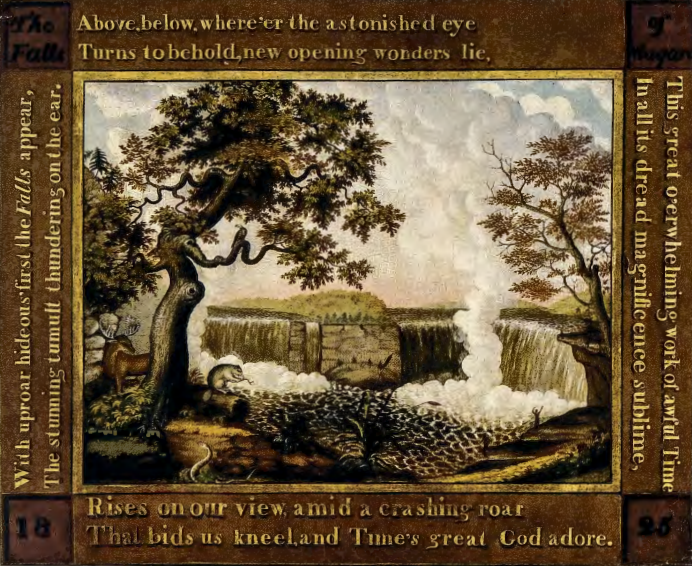

NIAGARA FALLS. Similar lessons were available to visitors at Niagara Falls. Niagara was depicted so frequently in gift books, travel literature, and popular prints that it was virtually impossible for anyone in the nineteenth century not to be familiar with its general appearance. Niagara became a required destination on every tourist's itinerary. Charles Dickens, visiting the United States in the early 1840s, brought back a "small piece of rock from the Niagara Falls" for his mother, and promised a friend a "phial [ vial] of Niagara water."

Like the Catskill Mountain House, Niagara offered its viewers a glimpse into God's secret workings. Edward Hicks (1789-1849), for example, a Quaker preacher and painter, recast the falls as a natural wonderland, a place where beaver, deer, and tourists all enjoyed the spectacle of God's presence (fig. 8.16). Hicks's painting, of 1825, domesticates the "awful" terror of the falls, converting Niagara from a spectacle of raw power to an emblem of God's omnipotence. In so doing, he places the sublime in the service of an American national "religion." He also eliminates the many signs of commercial development that surrounded the falls in the early nineteenth century. By portraying Niagara as a pristine landscape, Hicks converts it from an overdeveloped tourist site-with hotels, factories, and shops-to an unspoiled place of spiritual renewal. The falls embodied for Hicks, as for the many tourists who visited Niagara, a reminder not only of God's presence in the world, but of that special covenant that nineteenth-century Americans felt linked them, and the nation as a whole, to nature and nature's God.

Politics by Other Means: Thomas Cole

At the same time as Hicks was painting his view of Niagara Falls, Thomas Cole (1801-48), a twenty-four-year-old English immigrant, arrived in New York, pencils and sketch-book in hand. As a youth in Lancashire, in northern England, Cole had grown up in a family of artisans and skilled tradesmen in the early years of the Industrial Revolution. Emigrating as a teenager with his family to Philadelphia, Cole spent the next few years wandering through western Pennsylvania and Ohio as an itinerant artist. Eventually he studied drawing at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Arts and viewed with admiration the works of early landscapists on display in Philadelphia. He would come to revolutionize American landscape painting. Though never the leader of a formal school or academy, Cole spearheaded a movement among many New York artists to paint the mountainous regions north of New York City. Known loosely as the Hudson River School, these artists often traveled and sketched in the summer, when the weather was good, and then returned each winter to their studios in New York to compose oil paintings based upon their earlier sketches.

Steeped in European theories of art, Cole insisted on the "great and serious" calling of the artist. Unlike other early landscapists in America, he reacted strongly against any notion that his pictures should be literal transcriptions of what the eye sees. He believed instead in a "higher style of landscape," a way of imbuing the landscape with "moral and imaginative" power. He achieved that by sorting through and then combining sketches made outdoors into a built "composition" at his studio. Landscape composition for Cole was never a "dead imitation" of nature, but an imaginative leap into those "invisible" meanings that lie unseen on the other side of nature. He proclaimed that, "If the imagination is shackled, and nothing is described but what we see, seldom will anything truly great be produced in either Painting or Poetry."6

EXPULSION FROM THE GARDEN OF EDEN. In this painting of 1827-8, Cole places his sense of landscape painting's "higher style" in the service of social criticism (fig. 8.17). The painting is divided into two halves: Paradise on the right, and a turbulent and primeval landscape on the left. Eden has been painted according to the conventions of the beautiful-symmetry, balance, and harmony-while the fallen world leaps straight out of Burke's treatise on the sublime. Its volcanic peaks and writhing forms suggest dangers unimagined in Paradise, where a pair of swans glide gracefully upon an undisturbed lake. Their innocence contrasts with the tiny but poignant forms of Adam and Eve, who stand on the far end of the rocky bridge that separates Eden from the savage world before them. Exiting Eden, Adam looks back wistfully to the massive archway that now bars his return. The gentle diffusion of light in Eden has turned suddenly into a series of dagger-like spikes. Eve gazes downward and forward. Ashamed at her disgrace, she looks to the earth as the source of her future toil and sustenance.

Cole depicts Adam and Eve as Janus-like figures. Their divided posture summarizes, in miniature, the larger dualisms that define the painting: Eden and exile, light and darkness, sun and volcano, safety and danger. The Expulsion occurs for Adam and Eve as a fall into historical time, the great enemy, along with change. The left foreground is dominated by a towering tree blasted by a storm: unlike the changeless foliage of Eden, this tree will never return to its earlier state. It has been altered permanently by history. At its base, a vulture and wolf compete for the remains of a fallen animal. Their existence is defined by struggle and death. The bent form of the palm trees above them echoes, in turn, the hand-in-hand pose of Adam and Eve: mankind's fall carries all nature in its wake. Change and instability dominate the left half of the canvas, from the cascading waters below Adam and Eve to the spewing volcano directly above them. A large crack runs through the granite bridge they cross, suggesting that even the most stable of terrestrial forms might crumble at any moment.

Cole's painting pictures Eden as a stable, preindustrial landscape. It views the fallen world of Adam and Eve, by contrast, as a realm of history, a landscape defined by change, time, and death. And it defines the human condition as forever divided between memories of an agrarian past and prospects of a clouded future . Without so much as a single reference to factories, mills, or industry ( aside from the black smoke of the volcano itself), Cole provides a radical critique of the Industrial Revolution, which he defines not by its machinery but by its effects.

To understand Cole's critical response to industrialization, we need to direct our attention to an event that occurred in New York City in the summer of 1825. The Seneca Chief arrived in New York from Buffalo, the first steamboat to travel the newly opened Erie Canal. Completing her passage from Lake Erie to the Atlantic in nine days, the Seneca Chief inaugurated a new era in American life, ushering in a commercial revolution that would soon affect the lives of every inhabitant. The Erie Canal opened up Western wares to eastern markets at a time when horse-drawn wagons were so expensive that it cost almost as much to transport goods thirty miles by land as it did to ship them three thousand miles across the Atlantic. Built by Irish immigrants, who worked for less than $10 a month and a daily ration of whiskey-but who were later excluded from the ceremonies that marked the canal's debut-the Erie Canal represented the greatest engineering triumph of its day.

How did a young man raised in the British industrial heartland come to distrust the new commercial world represented by the Erie Canal? The answer lies in Cole's background. His parents had fled Lancashire during the long economic depression that followed the Napoleonic Wars. His father had drifted from one profession to another, incapable of supporting his family while in England and doomed, once the family settled in the United States, to a series of business disasters. For the young Cole, the lesson was clear: the Industrial Revolution was more curse than blessing. What others termed "progress," Cole experienced only as a source of loss and displacement. He distrusted change, and he interpreted the spread of commerce and industry-what he termed the "groveling pursuits" - as disruptions to the stable rhythms of a preindustrial landscape.

THE COURSE OF EMPIRE. Cole traveled to Europe in 1829, where he witnessed firsthand the political turmoil in Italy and the class hostilities leading up to the July Revolution of 1830 in France. Upon his return, he proposed a series of five paintings depicting the rise and fall of empire to Luman Reed, a self-made man of humble origins who had accumulated a fortune in the wholesale grocery business. By creating an art gallery in his New York home, Reed elevated his own social respectability. He opened the gallery once a week to the public. Cole's Course of Empire straddled the fireplace in Reed's art gallery: two paintings (one hung above the other) on both sides of the fireplace, and one painting, larger than the rest, over the mantle. Moving sequentially, the canvases are keyed to the times of day. The first painting in the series, The Savage State, shows a group of hunter-gatherers amidst a turbulent sunrise in early spring. The last picture, Desolation, features architectural ruins against an elegiac sunset. The three canvases in between (figs. 8.18- 8.20) represent corresponding moments in the progress of a day, a year, and an empire.

They also represent a profoundly pessimistic vision of Jacksonian society. Completed in 1836 during Andrew Jackson's second presidential term, Cole's five canvases suggest the fate awaiting any nation wed excessively to profit and self-interest. Cole viewed Jackson and the Democratic Party with unease. Comprised of a shifting alliance of Western farmers, Southern slaveholders, and small businessmen along the eastern seaboard, the Democratic Party embodied almost everything that Cole feared: commerce, partisanship, and materialism. Cole was especially critical of the myth of progress that underpinned Jacksonian optimism and justified westward expansion. Like many of his patrons he favored a politics of deference, one in which an educated elite exercised a form of benevolent stewardship over others. He feared the vulgarity and ignorance of the mass of men, and he saw the popularity of Andrew Jackson, whom Cole regarded as nothing more than a demagogue, as proof of his fears.

The Course of Empire might be read as Cole's meditation on the past, present, and future of the American republic. The series expresses not only his ambivalence about the relation of civilization to nature, but his deeper anxiety about the fate of the republic presided over by figures like Jackson and in the grip of unfettered capitalism. Cole countered antebellum notions of progress with an older and more aristocratic understanding of history as cyclical in nature. He believed that no society, however powerful, could endure forever. Civilizations, like individuals, begin in youth and glory but conclude in disillusionment and death. For Cole's American viewers, the issue was not whether his vision was correct, but whether it applied to them. Was the doom foretold in The Course of Empire- the passage from greatness to destruction- a record of past civilizations or a prophecy about the future of the United States itself?

The Course of Empire unfolds as a drama of hubris, both individual and collective. Cole's version of a modern hero-turned-demagogue appears at the lower left of Consummation, the third and largest canvas, presiding over a triumphal procession across the painting's foreground (see fig. 8.19). In ornate splendor, the red-robed figure surrounds himself, as Cole wrote, with "captives on foot, and a numerous train of guards, senators &c." This figure is a reference to Andrew Jackson, who was to Cole an American Caesar, a democrat turned military hero, conqueror, and usurper. Cole's emperor embodies all that can go wrong in society when wealth and status replace the simpler virtues seen in the previous canvas, The Pastoral State. Democracy turns into demagoguery, as a reverence for nature-the central theme of the earlier canvas- degenerates into a worship of power and empire.

The implications are clear. The very principles that propel civilization to its greatest achievements- the ability to reason and abstract, linked in practice with the capacity to conquer and subdue-now spell its doom. What had once existed in The Pastoral State as a celebration of mankind's higher faculties turns at the moment of Consummation into ostentation and self-congratulation. In that central canvas, despotism replaces republican virtue, and civilization exceeds its rightful limits.

The mountain peak that reigns majestically in the background of the first two canvases is barely visible in Consummation; its sides have been built over with roads, battlements, and terraces. Only in Destruction does nature reassert itself in the form of furious storms, billowing smoke, and roiling waves, and only in Desolation does nature finally settle in for the long, slow task of reclaiming the landscape from the human ruins that litter it.

Cole's series is thus not about nature but politics. The Course of Empire describes the ways that democracy, when left in the hands of the masses, turns into what anti-Jacksonians like Cole termed "mobocracy." As cities in the United States felt the first sting of the Industrial Revolution, as wage labor transformed artisans into deskilled workers, as neighborhoods began to swell with foreign immigrants, as the issue of slavery loomed increasingly across the boundaries between North and South, and as partisan party politics replaced earlier, more fluid political boundaries, Cole looked to the future with trepidation. The Course of Empire represents his effort to reinvent landscape art as a mode of moral critique.

Democratizing the Landscape: Asher B. Durand

Cole's ambivalence about the future ended abruptly in 1848, when he died unexpectedly at his home in Catskill, New York. At the time of his death, Cole was universally acclaimed as the "father" of American landscape painting. The great irony of Cole's career, however, lies in how much his successors ignored it. Cole was more revered than followed. His successors borrowed his forms- his ways of constructing a landscape- without also adopting his political point of view. Where Cole criticized Jacksonian optimism and cautioned against American dreams of empire, his followers reversed direction: they converted American landscape painting from an exercise in social criticism to an endorsement of American expansionism and Manifest Destiny.

KINDRED SPIRITS. We can see this move away from Cole's work in Asher B. Durand's (1796- 1886) memorial portrait to Cole, Kindred Spirits of 1849 (fig. 8.21). The picture yokes the painter Cole with the poet William Cullen Bryant on a stone outcropping within a wilderness scene reminiscent of Cole's own paintings. The names of the two men appear on a tree in the left foreground, while below the promontory a broken tree trunk that echoes Cole's blasted trees provides an emblem for his truncated life. The right half of the tree plunges toward the earth, while its left portion points to the ribbon of water that conducts the eye into the distance. The tree thus provides a metaphor for death and salvation. It directs the viewer away from its own fallen history in the foreground to the distant promise of the background sky.

The composition of the painting formalizes the tension between foreground and background, surface and depth. The rounded sweep of trees in the left corner of the canvas arches across the top and then bends down to the right, where it meets the answering line of cliffs. The movement creates a circular, doughnut-like form that opens at its center into the light-filled depth of the background, a movement reinforced by the angle of the promontories and the pointing figure of Cole, each directing the viewer toward the sky. The viewer must break out of the luxuriant foreground world in order to ascend along a visual pathway defined by stream and birds to a more generalized world of light-and spirit. The "kindred spirits" of the title refer not simply to Cole, Bryant, and the "sister arts" (painting and poetry), but to the larger relation of the individual to nature, and beyond that, of nature to a spiritual realm visible through it.

Where Cole emphasized danger in his landscapes, and created a sense of vertigo in his rock outcroppings, Durand domesticates Cole's wilderness into a womb-like enclosure that protects rather than threatens. Where Cole required his viewer to make a perilous journey across the canvas, Durand opens up the center of the canvas for the viewer's visual delectation. Where Cole addressed his viewer in stern and didactic tones, Durand offers instead an optimistic vocabulary of spiritual uplift. Durand abandons Cole's allegorical imagery for a version of nature that feels comforting and familiar.

There are reasons for this change. Durand's painting addresses the fundamental challenge facing American landscape painting in the two decades before the Civil War. What role does landscape painting play in a nation committed to westward expansion and commercial growth? In what ways can it affirm the expansive optimism of American society? Durand's answer to these questions is to democratize Cole's landscape. He removes the visual impediments. He promises a safe trip. And he offers two guides-a painter and poet- to assist us on our journey. Rather than admonish the viewer about the dangers facing the nation, Durand encourages the viewer to find personal and spiritual fulfillment in the landscape.

The trick lies in the eye. Kindred Spirits is first and foremost a painting about seeing. The viewer gains access to the landscape not by actually traversing it, but by taking imaginative possession of it. We see into the heart of nature, finding light, energy, and redemption in a Catskill landscape. For Durand, nature embodies those spiritual values most cherished by the middle classes: innocence, optimism, and progress. To voyage into nature is to voyage away from the social ills that might otherwise define daily life in the 1840s. What we do not find in Durand's Catskill scenery-what is pointedly missing-is a litany of social problems: no battles over slavery, no urban unrest, no economic anxiety, no class division.

The New National Landscape: Frederic Edwin Church

In the years after Cole's death, no artist was more responsible for reimagining the landscape as an embodiment of collective as opposed to private values than Frederic Edwin Church (1826-1900), Thomas C-ole's only student. Church took up the mantle of "heroic landscape" art in the United States. The son of a prominent Hartford businessman, he spent two years in the mid-1840s in Cole's studio, learning from him the "higher calling" of landscape composition. For Cole, the artist was always a solitary visionary. For Church, on the other hand, landscape painting was a way of taking the national pulse. Nature and nation were virtually identical concepts. In a manner that was more naturalistic and less stylized than Cole's, Church portrayed nature in tones that mirrored the national mood. In the 1840s and early 1850s, Church's imagery tended to be affirmative, expansive, and optimistic. & regional tensions increased and the country drew ever nearer to war, his work-like that of many of his contemporaries-became increasingly strident and melodramatic. With garish colors and turbulent skies, Church's New World landscapes grew apocalyptic in tone, visual reminders that the nation was edging ever closer toward conflict.

THE INFLUENCE OF CLAUDE LORRAIN AND THE "MIDDLE LANDSCAPE." The transformation of the landscape from a space of private feelings to an embodiment of national values depended historically upon two developments. The first was the creation of what scholars such as Leo Marx have termed the "middle landscape." Playing upon the notion of America as "Eden," viewers of nature sought neither wildness nor tameness, but a middle ground between the two. They turned to the paintings of the seventeenth-century French artist Claude Lorrain (1600-82) for their inspiration. Claude's canvases move from a foreground framed by trees, to a middle-ground space where Arcadian shepherds frolic, to a background of distant vistas and visionary prospects. For American artists, Claude's compositions provided a model for organizing space in terms of time. Each of the painting's planes represented a different stage in the history of the republic. When viewed in succession, they created a narrative of national progress. By moving visually from foreground to background, the viewer repeated the history of the nation as whole, a temporal progress from the clearing of the wilderness to the creation of an agrarian republic (see fig. 7.12).

Paintings of the middle landscape all told a single tale: the triumph of civilization over wilderness. The story was in the composition. In the foreground plane were to be found the remnants of wilderness, usually in the form of tree stumps and forest clearings. Such scenes stood as witnesses to an older frontier, an earlier moment in the history of the nation. The middle ground, by contrast, displayed farms, fences, and houses, reminders that what was once wilderness had subsequently been tamed. The middle-ground plane confirmed the success of American history: the larger transmutation of nature into an agrarian paradise. The background embodied the future, the space toward which society aimed, the place in the painting where land and sky, man's progress and God's promise, merged into one.

MERGING THE LOCAL WITH THE NATIONAL: NEW ENGLAND. The second ingredient crucial to the nationalization of the landscape is the conversion of local places and events into sites of collective importance. As sectional differences intensified in the decades before the Civil War, artists, writers, and intellectuals attempted to imagine a version of the landscape untouched by regional tensions. They sought to achieve in their art what they could not experience in their lives: a feeling of national unity. The more polarized the nation became-the more riven by divisions of city and country, black and white, wage earner and capitalist, North and South- the more pressure these artists experienced to heal or revivify the national mood. They did so by turning to local vistas and imbuing them with shared national values.

New England in particular came to embody the spirit of the nation as a whole. The demand for images of New England was fed by a theory known as "associationism," a belief that the landscape was important not for its intrinsic features, but for the historical associations that it conveyed. Thus, for instance, Church's New England Scenery, 1851, pictures what the viewer might think of as a "New England of the Mind," a composite landscape that combines pastoral conventions, historical allusions, and invented geography (fig. 8.22). The background mountain, for example, alludes to the central peak in Cole's Course of Empire. It helps Church stake his claim as a rightful heir to Cole's heroic style. It bears little resemblance to any actual peaks in New England. The small white church steeple nestled against the mountain alludes, in turn, to New England village life, recalling the original religious ideals of European emigration that associate the taming of the wilderness with freedom of worship.

The Conestoga wagon, in turn, suggested westward expansion to nineteenth-century viewers. By locating the wagon in New England-as opposed, for example, to St. Louis, the jumping-off point for settlers heading west in the 1850s-Church renders New England as the embodiment of a westering, national spirit. He also converts the notion of westward expansion from a social and economic phenomenon, a rather brutal process of land appropriation and anti-Indian policies, into a saga of collective spiritual journeying. What began in the seventeenth century as a religiously motivated quest continues right up to the present. Church's cozy, canvas-covered wagon carries the burden of civilization with it. It extends the values of a democratic republic to an untamed wilderness. In the process, it also affirms the centrality of New England to the national mission. The spirit of Plymouth Rock hovers over the pioneers at Pike's Peak.

New England was anything but a distillation of American values. Its leaders tended to be Whigs and dissenters from the national consensus. It staunchly opposed the Mexican War of 1846-8, seeing it as a barely disguised land grab by the South and West, an unwarranted opportunity to extend slavery westward. Its population tended to be better educated than the rest of the nation; its countryside was filled with factories and other harbingers of the industrial age to come; its woodlands were being cut down in order to provide fuel for the rapidly expanding railroads; and its farms were undergoing a precipitous decline as tillable land grew scarce and the soil became exhausted. Even its central ports, cities such as Boston, Providence, and New Haven, were all losing ground to New York, which by mid-century reigned supreme as the nation's commercial capital.

What New England possessed that the rest of the nation lacked was a rich civic mythology. Artists and writers increasingly came to associate New England's Puritan past with a history of civil and religious freedom. They defined the region's revolutionary tradition-the battles of Lexington and Concord, the Boston Tea Party, the saga of Paul Revere-as embodiments of a national spirit. They converted New England from a troubled industrial center to a spiritual standard-bearer for the nation. As its exports declined, its value as a center of culture increased. Paintings like New England Scenery combined with poems like Longfellow's "The Midnight Ride of Paul Revere" to celebrate a national history viewed through local New England eyes. Artists and writers converted the region from an increasingly marginalized commercial area to the embodiment of national-or at least Northern-values.

At the same time that Church was mythologizing the New England landscape, popular printmakers such as Currier and Ives were marketing images of American scenes for those who could not afford an original oil painting. In Home to Thanksgiving, for example, Currier and Ives translated a winter scene by the New England painter George Henry Durrie (1820-63) into a fond reminder of agrarian values and "the good old days" (fig. 8.23). The print links the New England countryside not only to the Pilgrim past, but to the contemporary rituals of family togetherness. New Englanders had long campaigned to make Thanksgiving a national holiday. Led in part by the efforts of the novelist Harriet Beecher Stowe, they succeeded when Abraham Lincoln (1809-65), at the height of the Civil War, proclaimed a national day of "thanksgiving" to be held annually on the last Thursday of each November. Home to Thanksgiving unites families and friends of different generations in a shared moment of renewal. The cold of the snow and sky is overcome by the tidy order of the New England farmstead. The animals are well tended, the buildings in good repair, and the wood supply abundant. The rectilinear composition-the use of horizontals and verticals to organize space-reinforces the viewer's sense of order. The general air of serenity in Durrie's landscape represents a larger national dream of harmony embodied in the New England farm.

GEOLOGY AND CHURCH'S "GREAT PICTURE": HEART OF THE ANDES. Despite our tendency today to segregate art and science into separate spheres, painters and scientists in the nineteenth century still viewed each other as close allies. Artists and illustrators regularly accompanied scientific expeditions to the American West, and scientists often turned to artists to help visualize and popularize their findings. In the early part of the century, geology was the queen of the sciences. Geologists had recently come to understand the world as having developed over millions of years. Their long view of history challenged the more traditional account in Genesis of a universe created in only six days. Though geologists were divided over whether change happened in rapid and cataclysmic events (a theory known as "catastrophism") or occurred instead in slow and gradual shifts, they were united in their understanding of geologic time as part of the "big picture." What brought painters and geologists together, as the art historian Rebecca Bedell has noted, was their shared commitment to "a careful observation of the natural world." Both "were dedicated to illuminating the diversity and order of God's creation. Moreover, both geologists and landscape painters were self-conscious participants in the antebellum enterprise of nation-building."7

Church traveled twice to South America, in 1853 and 1857, following the footsteps of the German naturalist Alexander von Humboldt (1769-1859). Humboldt's five volume Cosmos had portrayed the mountains of Ecuador and Colombia as ecosystems that were biologically diverse and geologically complex. He had also pointed to the larger unities of nature, which he understood as located in both science and religion. Church converted the lessons of Cosmos into an occasion to paint nature on a grand scale (5 feet 6 inches x 10 feet) in Heart of the Andes of 1859, which he termed the "Great Picture" (fig. 8.24). Humboldt had valued the Andes of South America for the way they embodied an unusually diverse range of New World ecosystems, from alpine valleys and meadows to majestic, snow-capped peaks, each flowing into the other within the span of a few miles. Following Humboldt, Church divides his canvas into a series of visual bands, set one on top of the other, and each representing a different geological or ecological zone. The foreground overflows with the vegetation of an alpine valley. In the right corner the viewer spots a tree fern, a large-leaved anthurium, and a climbing vine, all plants of the humid mountain valleys. The exposed rock face of the middle-ground cliffs-set in the right center of the painting against the vertical forms of the towering tree ferns-reveals the patterns of erosion that, for Humboldt, characterized the earth's crust. Humboldt believed in geological instability rather than stability. Church's landscape similarly portrays a world of change and accommodation. As one of the pamphlets accompanying the exhibition of The Heart of the Andes notes, the mountains in the painting, climbing one above the other, provide "tokens of primeval convulsions; proofs everywhere of change, building, razing, upheaval, sinking, and deliberate crumbling away."

At the same time that The Heart of the Andes displays a Humboldtian vision of ecological diversity, it also hints at a more traditional Christian narrative of spiritual salvation. Drawing on John Bunyan's Pilgrim's Progress, a seventeenth- century allegory popular throughout the nineteenth century, Church constructs his Andean landscape as a visual pilgrimage. The viewer commences his journey in the dense foliage of the lateral foreground, and soon encounters pilgrims praying before a cross on a sunlit ledge on the left. The voyage beyond is filled with earthly perils and tribulations, through the painting's middle ground, where the "war of light and shade" that defines the central mountain represents the "vigor and toil and perplexity" of the pilgrim's upward struggle. Only after ascending to the "region of final mysterious battle in clouds and darkness, on the verge of final triumph beyond the veil," can the viewer pilgrim at last take refuge in the "Dome of snow," the "emblem of permanent and infinite peace." By converting the biological diversity of the foreground into the worldly adversity of Christian allegory, Church knits together nature and nature's God into one seamless spectacle.

The theatrical nature of Church's painting is deliberate. The Heart of the Andes was displayed in cities from Boston to St. Louis, in theaters and auditoriums that Church rented specifically for the purpose (fig. 8.25). Church flanked the painting on both sides with drapes, pulling them back so as to suggest the view from a South American hacienda window. The picture's enormous walnut frame was carved, in turn, to resemble a window frame. Above the painting, the viewer discovered portraits of the first three presidents of the United States: George Washington, John Adams, and Thomas Jefferson. By placing the Founding Fathers above a South American landscape, Church revealed both the imperial ambitions of American policy (there was talk in the 1850s about American colonization of portions of South America and the Caribbean) and the linkage between "patriotism" and the landscape. Program guides were sold at the entrance to the exhibition, and the viewer was invited to view the painting through opera glasses, following the point-by-point references in the guidebooks as if moving visually through the Stations of the Cross. The dramatic effect was then completed by artificial lighting, a cordoned-off viewing space, and a general hush of reverence in the exhibition hall.

The Heart of the Andes marries science to religion, and then markets both to the new mass audiences that were developing in cities throughout the nation. Through diligent advertising, well-placed reviews, and splashy openings, Church helped transform painting from art to entertainment. His exhibition practices bypassed the usual procedures. Rather than displaying his art in group exhibitions mounted by the National Academy of Design or some other art institution, Church leapfrogged the traditional institutional arrangements and appealed directly to the public. He helped create a democracy of the curious and the paying. In the process, he paved the way for future artists who hoped to promote their own art in a profitable fashion. By weaving together art, science, religion, and nationalism, Church created an art of mass appeal. By the time of the Civil War, he had become America's first "superstar" artist. His paintings were the subject of public discussion; his exhibitions drew large crowds who often waited in line for hours to see a single work; and his canvases sold for enormous sums of money.

Feminizing the Landscape: Luminism

The Hudson River School of painting rapidly declined in popularity in the years following the Civil War. After the carnage of battle, the cheerful optimism of antebellum art began to look hopelessly old-fashioned, a trend reinforced by the growing attraction of American painters to the new and more cosmopolitan styles emanating from Europe. But before losing the public's attention, Hudson River School painting went through one final, glorious phase, called today "Luminism," a term that describes a recurrent concern with light, an absence of visible brushstrokes, and a feeling of stillness in many mid-century landscape paintings. Though the luminist painters were not linked together in any conscious fashion-they were never a "school" and they were not always aware of each other's work- they nonetheless share certain characteristics.

JOHN KENSETT. Those characteristics are most clear if we look at John Kensett's (1816-72) Eaton's Neck, Long Island, 1872 (fig. 8.26). Unlike Durand's Kindred Spirits, with its shifts in tone from foreground to background and busy display of details, Eaton's Neck is defined by compositional simplicity and the cessation of motion. The canvas is first and foremost planar in construction, composed of a series of flattened forms, each parallel to the picture plane, and each juxtaposed with the other. Eaton's Neck reduces its spaces to abstract, horizontal masses: a green and inanimate Long Island Sound; a beach and hillock whose lack of detail and general abstraction contradict the tendency of the land to recede diagonally into the painting's depths; and a flat, featureless sky occupying two-thirds of the painting's space. The work substitutes stasis for motion, and eliminates any visible brushstrokes, endowing the image with a hard, crystaline quality. Luminist paintings turn on a paradox: that images of depth and recession should instead produce spaces that are flat, abstract, and planar. Composed in the summer of Kensett's death, Eaton's Neck, Long Island produces an almost proto-modern vision of abstraction in its fidelity to the surface of the canvas.

FITZ HENRY LANE. This printer and painter (1804- 65) devoted his life to New England coastal scenes. In Owl's Head, Penobscot Bay, Maine, 1862, Lane pinions a solitary pilgrim-figure, staff in hand, twice: between water and land, and then again between boats and rocks (fig. 8.27). The empty boat to the left echoes the larger emptiness of the canvas, stilled and serene. It also mimics the tall ship at the painting's center. Though the ship's sails are unfurled, it appears to be motionless. There is no wake to disturb the glassy surface of Penobscot Bay. Instead, the abstract plane of the sky-occupying the upper two-thirds of the canvas-mirrors the flattened silver-blue of the bay, converting the painting's potential for motion into a smooth, mirror-like surface.

This emphasis on rectangles and planes in Owl's Head is set in counterpoint with an imagery of circles, from the rounded shape of the foreground rocks to the larger oval of the bay itself. More a protective cove, the bay is a place of safe mooring prior to the voyager's ocean-bound journey. That journey is imagined via the diagonal sightline that runs from the standing man across. the bay to the outlet at the right and then on to the ocean. It stands in tension with the static, rectilinear composition of the painting. Lane plays surface against depth, planar flattening against three dimensional recession. In the process, he opens the bay up into the larger world. The painting suggests that the cosmic is only a stone's throw from the local, that sacred vistas are available for those with an eye to see, that the voyage out into the world is, as Emerson suggests in his essay Nature, also a voyage into consciousness. And all the while the traveler need never have moved his feet.

SANFORD R. GIFFORD. At the same time that luminist paintings develop a flat, crisp, hard-edged quality, as if their spaces were sealed behind glass, they can also appear in a very different format. Art historians term this variant mode, with its misty atmospheres, its emphasis on haze, and its eagerness to dissolve objects into a larger visual unity, "atmospheric luminism." Sanford R. Gifford's (1823-80) October in the Catskills of 1880, a late work in the luminist style, scoops out the mass of land and mountains that tended to dominate earlier Hudson River School painting and fills the space instead with air (fig. 8.28). Gifford's subject is not the landscape itself but the light and color that define it. His nature lacks individual details. The trees behave as heliotropic sunflowers, bending their golden heads toward the white sun at the painting's center. The trees are painted in hues of gold and green. They function visually as colorful accents within the larger monochromatic unity of the painting.

Gifford does not see nature as the space of traditional antebellum landscape. The tunnel-like recession into the valley highlights the emptiness of space rather than its fullness. The painting's monochromatic unity asks the viewer to identify with nature rather than conquer it, to take it in at a glance rather than traverse it, front to back, over time . This altered vision of the landscape can be viewed as a willingness to understand nature as a coherent space of nurture and ecological unity. The viewer, according to this understanding, is not the conquering master standing at the precipice of the landscape ahead, but a humble team-player who fulfills a role within the larger-and integrated-workings of nature. This change in attitude reflects a larger historical transformation, from the conflicted world of Cole's nature and the nationalistic affirmation of Church's landscapes to an increasingly "sentimentalized" vision of nature as nurturing. Geologists abandoned the idea of catastrophic change in favor of slow and gradual evolution. Social reformers came to value nurture and growth over sudden and violent upheaval. Nature appeared less as powerful or punishing and more as benign and consoling. The landscape was valued for its unity and integration, providing a model for society as a cooperative enterprise, where restraint and accommodation prevailed over violence and competition.

Atmospheric luminism represents the triumph of "sentimental culture." The softening of forms, the emphasis on atmosphere, the focus on color and haze, the tonal unification of the canvas, all reveal a new effort by landscape painters to portray nature in more feminine terms. Their canvases, in effect, redefine nature-and by analogy, society itself-as an extension of the home: a warm and protective space. Instead of the majestic, operatic spaces of Church's pictures, the new canvases of luminism emphasize intimacy and immediacy. The viewer no longer navigates through a plot-filled narrative but is immersed in a welcoming world of light, air, and color. Atmospheric luminism signals to its audiences that the landscape has already been subdued. What lies ahead is not further conquest, but a deeper transformation of nature into culture.