8.1: Why Paint Landscapes?

- Page ID

- 232314

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)

If we were to ask an early-nineteenth-century audience why anyone would paint a landscape, we would receive a surprising answer. Landscape, for our nineteenth-century observer, had as much to do with matters of class as it did with nature. Look, for example, at John Trumbull's (1746-1853) Niagara Falls from an Upper Bank on the British Side, one of the earliest landscape paintings of a famous American landmark (fig. 8.1). The irony of the painting, to modern eyes, is that it shows us everything but the falls. Rather than focus on the plunging waters, Trumbull features the landscape that frames them: the small hill and cluster of trees in the foreground, the sedate pathways that help us navigate the painting's spaces, and the human figures who promenade around Niagara in formal attire. Trumbull's upper-class tourists are safe, dry, and removed from the water's turbulence. Trumbull has, in effect, divided the landscape into two realms: a region of wildness, energy, and power (the falls themselves), and a space of rational organization and control (the pathway and promenaders). The issue here is not nature, but the ability of a certain class of society to harness and contain nature's forces.

Trumbull's painting approaches the landscape symbolically. He is interested less in providing information about a specific locale, more in encoding the landscape as a microcosm of society. The mist and clouds act as a visual cap to Niagara's energies; they bind the swirling, but invisible, waters below, containing the water's force pictorially as surely as Trumbull's patrician culture attempted to control the social classes beneath them.

Trumbull viewed the fate of the early republic from an aristocratic vantage point. He believed that social order depended upon the wise judgments of a ruling caste, and expected the lower classes to defer to the leadership of this cultured-and propertied-elite. By the late 1790s, however, this viewpoint was on the wane. Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826), always skeptical of concentrated power, entered the White House in 1800. With Jefferson's presidency, the mantle of state power passed from an older elite to an increasingly popular and democratic-though still white and male- citizenry.

From this point of view, Trumbull's painting of Niagara represents an effort to reassert a patrician vision of society. He subordinates the power of Niagara Falls to the power of society, and imaginatively frames and binds tempestuous forces to render them safe. Trumbull envisions a world where class privilege extends seamlessly into a naturally ordered landscape.

We learn from Trumbull that landscape painting in the early nineteenth century has much to tell us about society. By presenting the viewer with a "world apart," an alternative space imagined as "rural" or "natural," it can embody a wide range of other concerns as well. The artist transforms nature into a symbolic place where social, cultural, and political concerns can be worked through safely. The choices the painter makes in composing his or her landscape-the arrangement of forms, the interaction of colors and shapes, the accessibility of the spaces, the viewer's point of view-all tell us about the painter's social world.

A Brief History of the Word "Landscape"

THE TERM " LANDSCAPE" originated in seventeenth-century Holland as landschap. It suggested a rural agricultural community. It made its way into the English language as landskip , and referred, when first used, not to the countryside itself, but to paintings-or prints-of the countryside. To see a landscape was not to go out into nature but to view a representation of nature, usually in a style borrowed from the Dutch or Italian painters of the seventeenth century. Over time, the term migrated from art to nature, and came to refer to the countryside itself. By the eighteenth century, a landscape could be either a painting or a place. Its appreciation, however, remained the province of those instructed in the niceties of aesthetic conventions. Such instruction came from travel guides, treatises on aesthetics, paintings, and prints-forms of experience available primarily to genteel classes.

Picturesque Beginnings

Edmund Burke, the eighteenth-century English philosopher, historian, and political thinker, wrote of the beautiful and sublime as opposing but complementary categories. According to Burke, the beautiful draws upon a "feminine" sensibility, and is linked to soft colors, sensual-and often curving-forms, smallness, symmetry, and harmony, provoking feelings of pleasure and sociability. The sublime, by contrast, resembles a powerful, punishing father, and evokes feelings of awe and terror. Sublime vistas are associated with masculine prowess, vague and obscure feelings, and brute force. As opposed to the self-contained and ordered nature of the beautiful, the sublime tends toward the rugged, the uncompleted, the infinite.

A third category, the picturesque, developed as a midway point between the beautiful and the sublime. This category derived from landscape compositions characterized by asymmetry, irregularity, surprise, and variety, a "middle ground" pastoral world neither wild nor over-cultivated, where farmers prosper and shepherds contemplate. Picturesque painting wrapped a mantle of nostalgia over the landscape, offering reassurance that country life was free from commercial contamination or modern technology. As seen in early-nineteenth-century American painting, the picturesque supplied a rapidly changing, modernizing society with a comforting, premodern image of itself.

LOOKING EAST FROM DENNY HILL. In 1800 Ralph Earl (1751-1801), a New England portraitist who had lived for several years in England, painted Looking East from Denny Hill, a large canvas that depicts a productive, rural Massachusetts landscape (fig. 8.2). Earl's contemporaries judged the painting accurate and "delightful." Framed theatrically by trees on the right and left, the scene shows the stages of haying- cutting, drying, turning, stacking, and loading on a haywagon. Beyond these harvest scenes are cultivated fields of various crops, each ripening in the sun. Woodlots crown hilltops, follow creek beds, and mark property edges; stone and wooden fences define fields and protect crops from wandering livestock. This is a landscape in which labor, land, and know-how produce crops, beauty, order-and money. It helps us understand the way beauty was understood at the time, and the ways that the landscape was ordered for aesthetic effect. An orderly vista was thought to provoke pleasure; and beauty derived from a larger social harmony.

VIEW NEAR FISHKILL. Almost two decades later, William Guy Wall (1792-after 1864), arriving in New York from England in 1812, painted scenes up and down the Hudson River, most of which were then engraved by another British immigrant, John Hill, for Wall's Hudson River Portfolio (1821-5). Wall's View Near Fishkill, like so much of his work for the Portfolio, tends to render the New York landscape as a timeless agrarian idyll peopled by self-sufficient farmers (fig. 8.3). There are no signs of commercial activity in the composition. Wall composes the canvas with a stand of leafy trees and a scattering of boulders on either side of the image. He then provides the viewer with a series of signs for navigating the landscape: the dirt path in the foreground, the ribbon of light across the river, and the passage, at the river bend, into the distant vista. This vista is framed, like an opened door, by two mountains that rise on either side of the Hudson River. Wall's composition is both traditional and new. It relies on picturesque conventions derived from seventeenth-century Italian painting: rustic figures, winding waterways, receding spaces, and asymmetrically framed vistas. Were it not for the contemporary costume of the figures at the water's edge, and the architecturally distinct shape of the two farmhouses, we might think we were viewing a scene in Italy.

And yet Wall hints at things to come. The visual flow of the painting-the route taken by the eye-differs from the physical pathways within it. Though viewers are invited to enter the painting via the foreground road, they are also asked to abandon the road and continue instead on an imaginative journey across the Hudson River. The two figures in the middle ground assist us on this journey, directing us to the distant mountains along the line of light that runs from the foreground path, through the figures and river, and into the hazy distance.

Wall's composition anticipates the element of spiritual odyssey that distinguishes Hudson River painting in the following decades. But his formulaic approach tends to overshadow this innovation. For Wall, conforming to the visual conventions of the picturesque is more important than embodying spiritual values. Though his publisher boasted that his paintings were completed on the spot rather than synthesized in the studio, Wall's art demonstrates very little of this "faithful attention to nature."

Picturesque Parks

The picturesque aesthetic proved to be so compelling a way of looking at the landscape that it came to dominate social life as well as fine art production. Middle-class Americans turned to parks, gardens, and, ironically, cemeteries, to provide a respite from the urban environments that came increasingly to dominate their lives. As more and more people moved into cities, they adapted to urban conditions by seeking out non-urban spaces. City dwellers sought natural settings where they could meditate quietly, away from the bustle of the city. They longed for renewed contact with their own agrarian roots, and they sought to instill a taste for nature among the immigrant populations residing in the city. This hunger for the~countryside stemmed from a Jeffersonian ideology that linked the success of the republic to its small landholders. Jeffersonians believed that good citizenship required economic and social independence, precisely the sort of freedom exemplified by the yeoman farmer. The dilemma for the nation's new urbanites was how to preserve those agrarian values in an increasingly commercial society.

The solution they invented was twofold: either bring the city to nature or nature to the city. They achieved the first in a rather unexpected way: by designing suburban cemeteries at the edge of the city. The writer Washington Irving was influential in changing public opinion about death and burial. He urged people to convert the graveyard from a place of "disgust and dismay" into a site for meditation by transforming the cemetery into a picturesque rural park. (Even the use of the word "cemetery" was new. A more gentle word than the Puritan 'burying ground," it derives from the Greek for "sleeping room," and presented death in softer terms.) New ideas about death focused on melancholy, and the comfort offered by nature. Weeping willows and burial urns began to replace winged skulls and cherub's heads on tombstones.

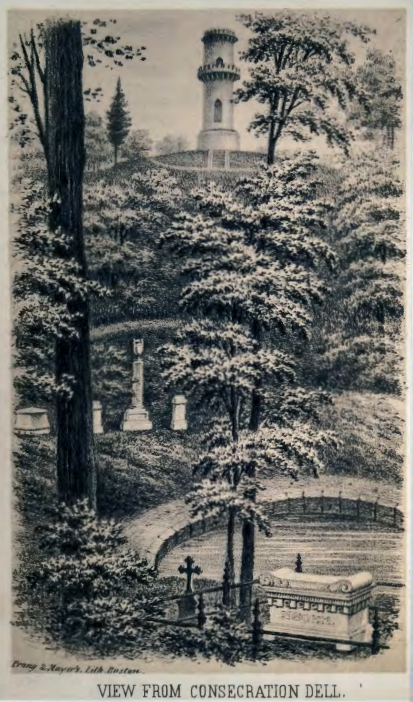

MOUNT AUBURN. One of the earliest of these picturesque cemeteries, Mount Auburn, opened outside Boston in 1831 (fig. 8.4). Mount Auburn cemetery was fashioned according to landscape principles imported from English country estates. Situated on a popular picnic site with beautiful views of Boston, it incorporated all the central elements of picturesque design: rolling hills, variegated vistas, ponds and lakes, and a series of paths winding among the trees and shrubbery. The cemetery proved extremely popular, a site where the living, as well as the dead, could find peace. According to the architect Andrew Jackson Downing, Mount Auburn Cemetery attracted thirty thousand visitors in a single season in 1849.

What made cemeteries like this so attractive- Philadelphia, New York, and St. Louis soon opened up their own rural cemeteries-was the way they provided a counterbalance to the stresses of "modern" life. Visitors were encouraged to wander contemplatively through the landscape and to meditate on the lessons that nature taught. Those who strolled through the cemetery honored the dead by sharing with them the serenity of its picturesque surroundings. Joseph Story, a speaker at the opening dedication of the cemetery, noted the way that the vistas at Mount Auburn allowed "the rivalries of the world" to "drop from the heart." Story proclaimed that at Mount Auburn "the selfishness of avarice will be checked; the restlessness of ambition will be rebuked."

Individuals were buried in family plots there. Unlike the older, urban cemeteries, where graves and cenotaphs jostled unceremoniously against each other, Mount Auburn and other private cemeteries offered families the opportunity to remain together through eternity. The rural cemetery movement dovetailed with the growing emphasis on family life and sentimental values in Victorian society. With their picturesque surroundings and genteel atmosphere, such cemeteries converted death from a Puritan-like punishment for sin-a release from the mortal body-to a sentimentalized opportunity for family togetherness.

Memorializing Death

THERE WERE MANY WAYS to mourn in the nineteenth century. Women often cut locks of hair from the dead, for example, and fashioned them into elaborate flower-like brooches. They also sewed memorial embroideries. Hundreds have survived from New England and the Mid-Atlantic states. These typically depict one or more mourners, a memorial urn, and a weeping willow tree in a pastoral setting. They were sometimes supplemented by portrait faces painted by expert miniaturists, and epitaphs printed on cloth and stitched to the fabric. Memorial embroideries were usually elaborately framed to hang in the home as a memento of a dead family member. Interestingly, the idealized images on these embroideries pre-date the actual use of a pastoral landscape as a cemetery. It is as if people first visualized the ideal setting in art, and then set about creating it in life.

While many quilters made remembrance quilts out of fabric cut from the clothing of the dead, Elizabeth Roseberry Mitchell (1799-1857) of Kentucky devised a quilt that served ingeniously as both a family record and an object of mourning (fig. 8.5). She created a pieced quilt in a pattern known as the LeMoyne Star. Instead of the customary large star at the center, however, she sewed a graveyard. A larger fence on the quilt's border echoes this interior enclosure.

Though Mitchell sewed this quilt after the deaths of two of her sons in 1836 and 1842, she envisioned it as a family record- not only of herself, her husband, and their eleven children, but their future families. In addition to appliqueing some two-dozen coffins (most on the perimeter of her quilt), Elizabeth Mitchell hand-stitched the outlines for many more possible coffins along the fencing that borders the quilt. Most of the coffins have strips of paper or cloth attached to them, labeled with family names. She also embroidered trees and flowering vines around the fencing of the central graveyard, making it a more hospitable place for the coffins that were eventually moved there.

After the artist's death, her daughter Sarah Mitchell Stallcup assumed responsibility for the quilt. She sewed her mother's coffin in the central graveyard, joining those of her brothers John and Mathias. Sarah Stallcup also had the unhappy task of adding the coffins of her own husband and her baby. Neither these coffins, nor those of spouses or other babies of the next generation, were put in the graveyard at the center of the quilt. The graveyard was reserved instead for the thirteen immediate members of the artist's family; in addition to the four coffins resting there, hand-stitched outlines indicate where nine others might fit. After 1870, no more coffins were moved and no more cloth strips with penned notations were added. Though the quilt passed down through the Mitchell family for ninety more years, it ceased to serve as a family death register. It became instead a reminder of the woman who had devised such a remarkable quilt.

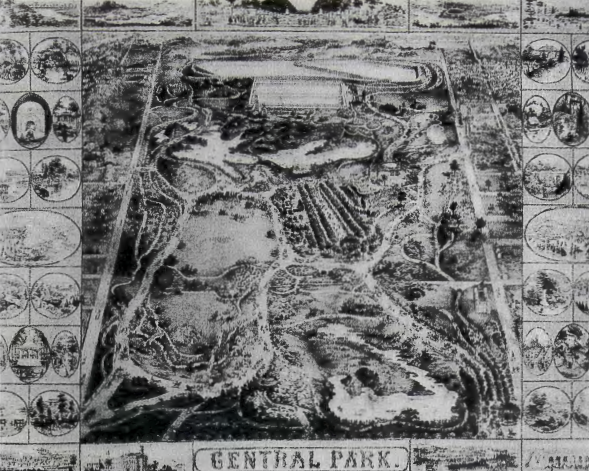

CENTRAL PARK. For those without the option of a rural burial, or a leisurely picnic among the dead, the next best thing was to bring nature to the city. Cities such as New York took their cue from the success of the rural cemetery movement to create new urban parks based on picturesque principles. The first of these urban parks was Central Park (1856-83), designed by Frederick Law Olmsted (1822-1903) and Calvert Vaux (1824-95) (fig. 8.6). Together with the Bois de Boulogne in Paris, Central Park was the first large urban park designed for public rather than private use. The park transposed picturesque vistas familiar from English country houses into a new type of shared urban space. Olmsted and Vaux created a variety of different landscape terrains: meadows, rolling hills, lakes, woodlands. They worked with the local topography, at the same time radically transforming what they found to give · it a picturesque look. Their goal was to create an idealized nature in the middle of the city, offering New Yorkers a place of rejuvenation.

For elite and middle-class urbanites, this meant a place to promenade, to see and to be seen, while enjoying the restorative power of the landscape. For immigrant and working-class New Yorkers, however, Central Park represented a break from the regimented world of factories and labor. Their desire to use it as a sometimes rowdy escape from the world of work contrasted with their employers' desires, not only to maintain an air of quiet dignity in the park, but to convert it into the equivalent of a giant, outdoor civic lesson. Middle-class Protestant New Yorkers hoped that Central Park would provide the growing number of Catholic working-class immigrants with a salutary dose of agrarian virtue. They viewed its meadows and woodlands as civilizing spaces, places where nature could exercise its healing influence upon workers otherwise doomed to the unnatural temptations of the city.

To the consternation of Central Park's working-class constituents, Olmsted and Vaux tried to ban sports and playing fields, which they felt were distractions from a more genteel and contemplative experience of nature. This debate over the proper use of Central Park continued well past its construction, as New York's working-class and immigrant populations battled the park's more well-to-do neighbors on Fifth Avenue and Central Park West over issues of proper land use well into the twentieth century. So keen was their desire to separate city from country, and in the process to preserve the nation's agrarian heritage, that Olmsted and Vaux sank the roadways that cross the park below the sightlines of those promenading through it.

They believed that any exposure to urban traffic would spoil the serenity of the park's spaces (fig. 8.7). After the success of Central Park, Olmsted continued to design picturesque landscapes, including the Boston and Chicago Park systems and the Stanford University campus.

Picturesque Architecture: Andrew Jackson Downing

Olmsted's partner in the design of Central Park, Calvert Vaux, had previously worked with Andrew Jackson Downing (1815-52), the leading popularizer of picturesque aesthetics in the United States. In magazine articles and pattern books published in the 1840s and 1850s, Downing argued with the zeal of a born-again reformer for the power of picturesque settings to counter the debilitating effects of modern life. He focused on domestic life, seeing property ownership and the family as the bulwark of a democratic culture, and he believed that the physical style and layout of a house profoundly influenced the spiritual state of its inhabitants. Downing designed what he termed "villas" for the upper classes, "cottages" for the middle classes, and "farmhouses" for the working classes. Though each style derived from familiar types of European domes- ,. tic architecture, they all drew upon the picturesque as an antidote to the excesses of commercial life. Downing did not actually oppose modern life. He sought instead to buttress the family against that unholy trinity of modern forces: urbanism, capitalism, and industrialism.

His picturesque architecture represents an early form of environmental reform. Downing sought to counteract the effects of city life by surrounding people with many restorative "natural" forms.

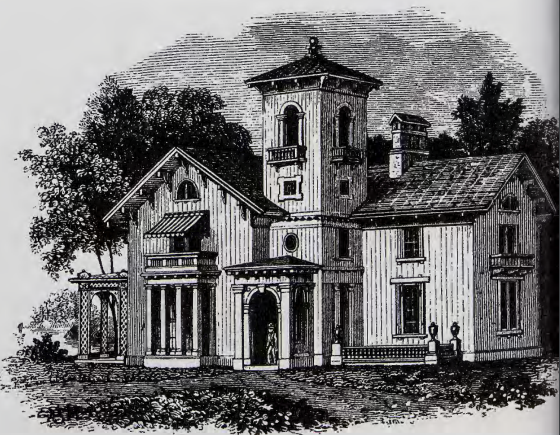

Downing designed homes that embodied what he felt was the moral power of the surrounding landscape. Because nature was picturesque and irregular, the ideal home should also be varied, "organic," and never merely "functional." A true home was more than a place of shelter; it had to express refined feelings and elevated truths. To that end, Downing advocated forms that harmonized rather than contrasted with the landscape. He urged that homes be painted in neutral colors. He favored large and simple porches so that nature's influence could be felt right up to the front door. And he doted on Italianate architecture and Gothic Revival homes. Taking his cue from the Tuscan countryside, Downing created Italianate houses with asymmetric facades, a flat-roofed tower for surveying the landscape, a spacious veranda for relaxing with nature, and an overall rectangular "footprint" for fitting comfortably into suburban lots (fig. 8.8).

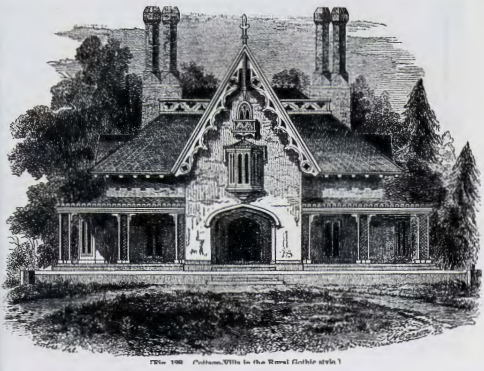

ROTCH HOUSE. One of Downing's most famous gothic cottages, the Rotch House, c. 1845-7, adapted an older tradition of British domestic architecture to the standard four-room Georgian house (fig. 8.9). With its steeply pitched roofs, sharply pointed dormers, gables, and ornaments, the Rotch House directed the attention of its inhabitants upward, drawing on a tradition of spiritualizing architectural forms. In an age of evangelical revivals, the house provided the Christian family- increasingly nuclear and isolated-with a space designed to be both nurturing and uplifting. The arrangement of the rooms, in turn, reinforced growing class divisions. As the architectural historian Clifford Clark, Jr., has noted, the working space of the kitchen was physically segregated from the social space of the family by closets, pantries, and servants' stairwells. This separation provided both groups-family and servants with privacy and the liberty to converse amongst themselves. While the prosperous middle-class family enjoyed its picturesque surroundings, a coterie of servants labored invisibly "off-stage." 1

Downing's homes reflected the gendered values of their Victorian inhabitants. The exterior of a Downing house, as the architectural historian Dell Upton has noted, projected an authoritative "masculine" look, while the landscape and gardens, with their more passive and softening influence, suggested the spiritualizing influence of the wife and mother.2 Downing emphasized "honesty" and "truth" in his domestic architecture, by which he meant that the appearance of a house should reflect the social status of its occupants. Like so many other Victorians, Downing was deeply preoccupied with the anonymity of urban life. His houses countered the loss of identity on the street by reinforcing class distinctions in the home. Through its size, style, and embellishments, a Downing home announced what sort of people inhabited it. In a society "filled with an increasing number of aliens and immigrants," Downing's homes reasserted the importance of social distinctions, providing a clear vision of social place and hierarchy.

The Anti-Picturesque: Functionalism and "Yankee Ingenuity"

While Downing turned to nature-and to European architectural forms-to counteract the effects of modernization, others, like the sculptor and art critic Horatio Greenough (1805-52), moved in the opposite direction. Greenough was a "functionalist." He wanted no Victorian fripperies, no decorative add-ons, and no aesthetic flourishes. In a series of essays collected in 1852 under the title Travels, Observations, and Experiences of a Yankee Stonecutter, Greenough inveighed against Greek temples, embraced vernacular design, and articulated a theory of art that presages twentieth-century modernist aesthetics.

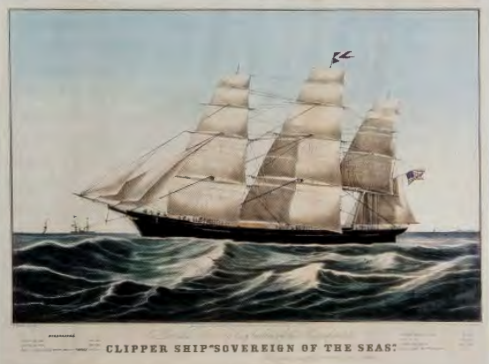

Greenough held up America's nameless artisans and builders as the paramount designers. They, he argued, followed the surest pathway to efficiency and beauty: nature. "Observe a ship at sea!" he implored, "What academy of design, what research of connoisseurship, what imitation of the Greeks produced this marvel of construction?" (fig. 8.10). By listening to nature rather than imitating historical models, American shipbuilders, in Greenough's day, had designed the swiftest ships on the oceans. They had also designed extraordinarily beautiful objects: "Let us consult nature," Greenough said, if we wish to produce a "compact, effective, and beautiful engine."

For Greenough, the artisan's "consulting" nature was the right move. It allowed American artists and architects to employ Greek principles rather than imitate Greek structures. They could do this, he argued, by an "unflinching adaptation of forms to functions. " The result would be both beautiful and useful: " I define Beauty as the promise of Function."3

MECHANIZED MANUFACTURE. Greenough relished the ease with which artisans dispensed with traditional forms and embraced their own ingenuity. Their goal was efficiency, and they sought to economize on materials, time, and labor, while maximizing speed. The result was profitable patents for some, and cheaper, more efficient manufactured goods for many. The mechanisms for steaming and bending wood, for instance, developed by Samuel Gragg of Boston and patent~d in 1808, allowed him to produce fashionably curvaceous sidechairs for a fraction of the cost of those produced by carving away wood from a solid block (fig. 8.11). Both European and American furniture-makers quickly took full advantage of this technology. In the realm of transportation, the invention of the lattice truss by Ithiel Town of New Haven, Connecticut, capitalized on the rigidity of triangles to create a light, adaptable, easily assembled bridge with simplified abutment requirements which was therefore cheaper and faster to build. Pattern books then provided builders across the United States with information about the lattice truss. Of the hundreds, perhaps thousands, of wooden Town truss bridges built to span rivers and streams from Maine to Georgia in the nineteenth century, several survive and are still in service.

The one illustrated here was built using a Town truss about 1830 by Horace King, slave of John Godwin, contractor, in Meriwether County, Georgia (fig. 8.12). Spanning Red Oak Creek, its roof and board-and-batten side sheathing protect the wooden structural members from the weather, and hence from decay.

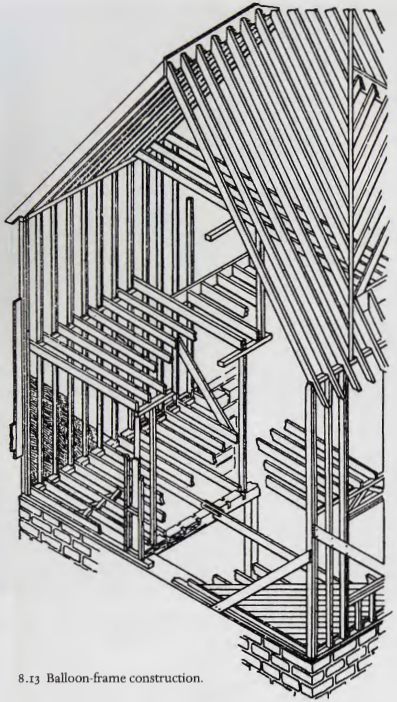

BALLOON FRAME CONSTRUCTION. An even more important innovation of this period affecting all subsequent construction is the balloon frame (fig. 8.13). It was invented in Chicago in 1833 by Augustine D. Taylor, who built a small church for only $400 ( an incredibly low sum even then). Taylor's church was crafted of light 2-inch by 4-inch timbers and nails, rather than heavy, individually cut structural members that were morticed and tenoned together joint by joint. Using fewer and less-skilled workmen, less wood, and much less time, this new technology depended on the development of mechanically made nails (purchased for less than the cost of the tax on nails in Europe) and standardized sizes of lumber. These structures went up so fast they appeared to 'balloon" into the landscape. The technology was promptly adopted, especially in the fast-developing Midwest. It continues to be standard carpentry for houses, in this country and elsewhere, today.

INTERCHANGEABLE PARTS. This drive to build ships, houses, and bridges more cheaply, quickly, and efficiently also brought substantial changes to the daily life of artisans, mechanics, and workers. Because shops became larger in the early nineteenth century to take advantage of volume production and distribution of wares, the capital necessary to start a competitive business rose dramatically. Fewer and fewer artisans could rise above wage labor status. At the same time, the new concentration of labor meant increasing specialization on the part of each journeyman, and hence a greater distance from the finished product. As early as 1800 journeymen identified themselves as a class and engaged in oppositional politics with masters on a city-wide basis in New York, Hartford, and elsewhere.

New relations between master-entrepreneurs and journeymen, and new tools-the power drill, trip hammer, and power loom-were not the only changes in the workshop culture in antebellum America. Perhaps the most pivotal innovation was the principle of interchangeable parts. Just as standardized lumber contributed to the development of the balloon frame , standardized interchangeable parts in manufactured goods enabled businesses to make objects more quickly and inexpensively, required less training for workmen, and led to the development of what has been called "the American system of manufactures," with rationalized machine-assisted movement of goods through an assembly-line manufacturing process. Eli Whitney's gun factory in New Haven, Connecticut, pictured in William Munson's painting of 1826-8, made the first guns with interchangeable parts (fig. 8.14). They worked better, were easier to repair and cheaper to produce than guns made individually from start to finish by a single, highly trained craftsman. Whitney built worker housing- looking like interchangeable parts-suggesting that workers were also, now, more interchangeable, which, in fact, was the case. Manufacture now concentrated skill in the hands of a single designer, requiring less skill and ingenuity on the part of fabricators and assemblers. The passion for efficient forms of industrial production would culminate, a century later, in Henry Ford's invention of the moving assembly line.