6.6: Story- Pan and Syrinx

- Page ID

- 47176

The Wood-Folk

Adapted from Old Greek Folk Stories Told Anew by Josephine Preston Peabody, $\ccpd$

There is the god of the forest, the goat-god named Pan. He is the son of mischievous Hermes and a mortal shepherd’s daughter. When he was born, his mother saw his little horns, goat ears, and goat hooves and let out a scream so loud that other people came to see what had happened, and then also screamed and ran away from the little fuzzy baby. However, Hermes laughed and adored his little son. He wrapped him up in a rabbit fur blanket and took him to visit the gods and goddesses on Mount Olympus. They were all amazed at how odd he looked, but at the same time loved him and his little goat ears as much as Hermes himself. Thus, he was named “Pan”, because “all” of the gods loved him. Hermes then brought little Pan back to help take care of flocks of animals on the earth.

Pan led a merrier life than all the other gods together. He was beloved by shepherds and countrymen, and by the fauns and satyrs, birds and beasts, of his own kingdom. The care of flocks and herds was his, and for a home he had all the world of woods and waters; he was lord of everything outdoors! But he felt no pressure by this–Pan spent the days in laughter, music, and dance among his fellows. Like him, the fauns and satyrs had furry, pointed ears, and little horns above their eyebrows; in fact, they were all enough like wild creatures to seem no strangers to anything untamed. They slept in the sun, piped in the shade, and lived on wild grapes and the nuts that every squirrel was ready to share with them.

The woods were never lonely. A man might wander alone in the forest and think himself friendless; but here and there a river knew, and a tree could tell, a story of its own. It was filled with nymphs, female spirits of nature. Beautiful creatures they were, that for one reason or another had left off human shape. Some had been transformed against their will, so that they might do no more harm to their fellow humans. Some were changed through the pity of the gods, so that they might share the simple life of Pan, mindless of mortal cares, glad in rain and sunshine, and always close to the heart of the Earth.

Many nymphs and spirits were there in the woods. There was Daphne the laurel, who Apollo loved but she did not return his love, so she turned herself into a laurel tree to escape him. Now Apollo takes branches from the tree and gives them to winners because he thinks that he won her over. Hyacinthus (once a beautiful youth, killed by accident), who lives and renews his bloom as a flower,— these and a hundred others. Even the weeds were friendly.

As for Pan, only one thing made him sad–although he had the love of everyone else, he could not get the love of any nymph, and was always following and chasing one after another. Pan even tried to get close to Echo, but she saw his goat legs and ran away, attempting to let out a yell.

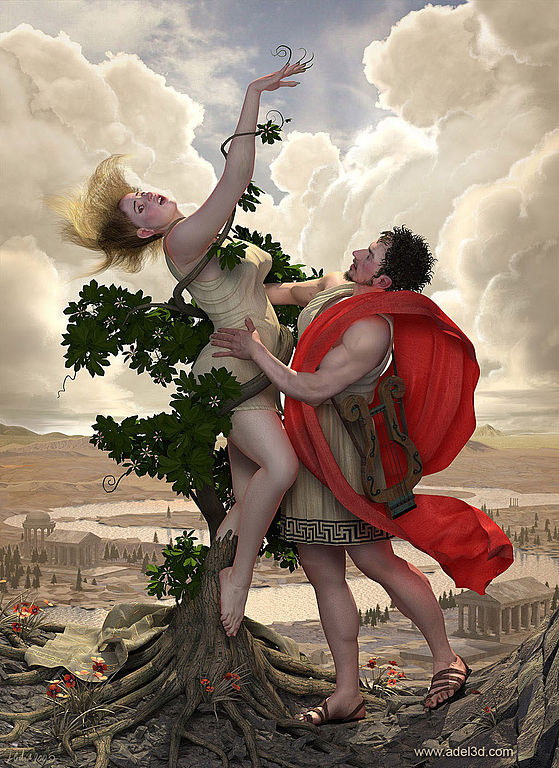

One day, when he was hanging out in Arcadia, he saw the beautiful wood-nymph Syrinx. She was running to join Diana hunting, and she herself was as swift and lovely as any bright bird that one longs to capture. So Pan thought, and he hurried after to tell her. But Syrinx turned, caught one glimpse of the god’s shaggy hair and bright eyes, and the two little horns on his head, and she sprang away down the path in terror.

Begging her to listen, Pan followed; and Syrinx, more and more frightened by the patter of his hooves, never heeded him, but went as fast as light until she came to the edge of a river. Only then she paused, praying to her friends, the water-nymphs, for some way to escape. The gentle, confused creatures, looking up through the water, could think of nothing but one plan.

Just as the goat god overtook Syrinx and stretched out his arms to embrace her, she vanished like a mist, and he found himself grasping a cluster of tall reeds. Poor Pan!

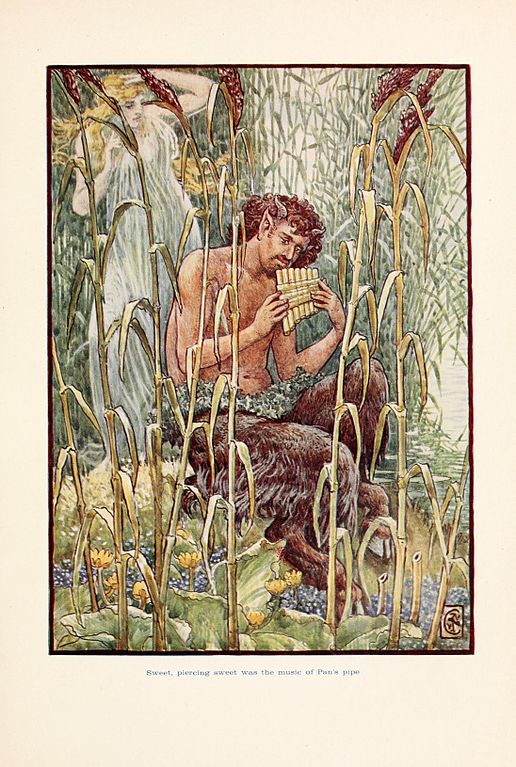

The breeze that sighed whenever he shook the reeds and made a sweet little sound,—a sudden music. Pan heard it, half consoled.

“Is it your voice, Syrinx?” he said. “Shall we sing together?”

He tied together a number of the reeds side by side; to this day, shepherds know how. He blew across the hollow pipes and they made music!

Did you know?

In addition to the two phrases above, we get the word “laureate” from Apollo’s story. A laureate is the recipient of honor or recognition for achievements in an art or science, such as literature, poetry, military award, or the Nobel prizes.

Also if you have any friends named Laura or Lauren, their names mean honor and victory, coming from the laurel tree meaning.

Don’t forget about this story is how we got the pan flute!

Vocabulary from the Story

Answer the following questions. Check your answer with a partner.

- In this story, they explain why Pan is named “Pan”. As we learned before, “Pan” means all. However, we get another word from Pan that is not related to pan meaning “all”, and that is the word “panic”.

- What does “panic” mean?

- In what parts of speech can it be used?

- How is the past tense verb spelled?

- How is this word related to the god Pan?

- Make a sentence using “panic” as a verb.

- Make a sentence using “panic” as a noun.

- We also get the word “syringe” from Syrinx in this story.

- What is a syringe?

- How is this word related to Syrinx?

- We also get the idea of laurels from the story of Apollo and Daphne. Read the definition from Wikipedia below for two phrases from this story: In common modern idiomatic usage, it refers to a victory. The expression “resting on one’s laurels” refers to someone relying entirely on long-past successes for continued fame or recognition, where to “look to one’s laurels” means to be careful of losing rank to competition.

Think of an example of how each phrase could be used.

Comprehension Questions

Answer the questions according to the reading. Paraphrase your answer.

- How would you describe how Pan looks?

- Who are Pan’s parents?

- What is Pan the god of?

- How did Pan get his name?

- What are satyrs?

- What is the story about Apollo and Daphne?

- What happened to Hyacinthus?

- Who is Syrinx?

- What did Syrinx do when Pan tried to chase her?

Critical Thinking Questions

Answer the following questions. Compare your answers with a partner.

- What three phenomena are explained in this story?