4.2: Story- Perseus and Medusa

- Page ID

- 47156

Perseus and Medusa

Adapted from The Myths and Legends of Ancient Greece and Rome by E. M. Berens, $\ccpd$

Perseus, one of the most famous of the legendary heroes of ancient times, was the son of Zeus and Danae, daughter of Acrisius, king of Argos. An oracle foretold to Acrisius that a son of Danae would be the cause of his death, so he imprisoned her in a tall tower in order to keep her isolated from the world. Zeus, however, descended through the roof of the tower in the form of a shower of gold, and the lovely Danae became his bride.

For four years Acrisius had no idea this happened, but one evening as he happened to walk by Danae’s room, he heard the cry of a young child from within, which led to the discovery of his daughter’s marriage with Zeus. Enraged, Acrisius commanded the mother and child to be placed in a chest and thrown into the sea.

But it was not the will of Zeus that they should die. The chest floated safely to the island of Seriphus, where Dictys, brother of Polydectes, king of the island, was fishing on the seashore and saw the chest abandoned on the beach. Pitying the helpless condition of its unhappy occupants, he led them to the palace of the king. Polydectes knew he wanted Danae as his wife the instant he laid eyes on her. Yet for many years Danae and Perseus remained on the island, where, unbeknownst to Polydectes, Perseus received an education suitable for a hero from the best teacher available–Achilles’, Hercules’, Jason’s, and Theseus’ teacher, Chiron the Centaur.

As he grew up, Perseus believed Polydectes was less than honorable, and protected his mother from him; then Polydectes plotted to send Perseus away on a long, impossible task to humiliate him, or even better, kill him so that he would stop interfering with his plan to marry Danae. He held a large banquet where each guest was expected to bring a gift, but Perseus was unaware of this custom, so he asked Polydectes to name the gift; he would not refuse it. Polydectes held Perseus to his reckless promise and demanded the head of the only mortal Gorgon, Medusa, whose gaze turned people to stone.

To accomplish this, Athena advised him to find the Hesperide Nymphs, who only the Grææ knew where they lived. Perseus started on his expedition, and, guided by Hermes and Athena, arrived, after a long journey, in the far-off region, on the borders of Oceanus, where the Grææ lived. He at once asked them for the necessary information, and on their refusing to grant it he stole their single eye and tooth, which he only gave back to them when they gave him full directions with regard to his route. He then proceeded to the land of the Hesperides, from whom he may obtain the objects crucial to his purpose.

From the Hesperides he received a bag to safely contain Medusa’s head. Zeus gave him an adamantine sword and Hades’ helm of darkness to make him invisible. Hermes lent Perseus winged sandals to fly, and Athena gave him a polished shield. Perseus then proceeded to the Gorgons’ cave.

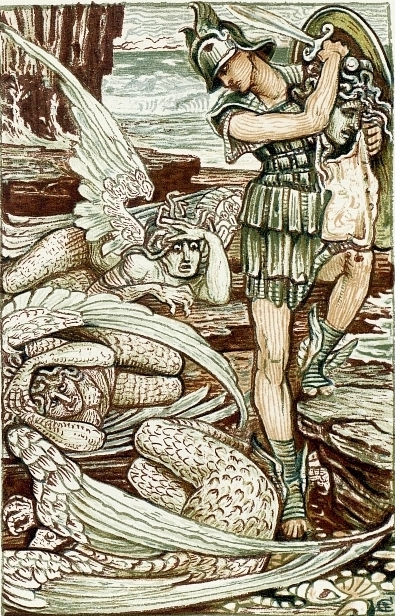

Equipped with the magic items, he attached to his feet the winged sandals and flew to the land of the Gorgons, whom he found fast asleep in a cave. Now as Perseus had been warned by his heavenly guides that whoever looked upon these weird sisters would be transformed into stone, he stood with his face turned away from the sleepers, and looked at them through the reflection in his bright metal shield. Then, guided by Athena, he cut off the head of the Medusa, which he placed in his bag. As soon as had he done that, from Medusa’s headless body there sprang forth the winged horse Pegasus, who flew up into the sky. He now hurried to escape the pursuit of the two surviving sisters, who, awoken from their sleep, eagerly rushed to avenge the death of their sister.

His invisible helmet and winged sandals here came in handy; for the former concealed him from the view of the Gorgons, while the latter carried him swiftly over land and sea, far beyond the reach of pursuit. In passing over the burning plains of Libya the drops of blood from the head of the Medusa oozed through the bag and falling on the hot sands below produced many-colored snakes, which spread all over the country. Droplets of blood that landed in the ocean created coral reefs underwater.

Perseus continued his flight until he reached the kingdom of Atlas, of whom he begged rest and shelter. But as Atlas protected the Garden of the Hesperides, where every tree produced golden fruit, he was afraid that this hero who just killed the monstrous Medusa might also destroy the dragon which guarded it and then steal his treasures. He therefore refused to grant the hospitality which the hero demanded. So, Perseus, irritated at Atlas’ refusal, reached into his bag and pulled out the head of the Medusa, and holding it towards the king, transforming him into a stony mountain. Beard and hair erected themselves into forests; shoulders, hands, and limbs became huge rocks, and the head grew up into a rocky peak which reached into the clouds.

Perseus then resumed his travels. His winged sandals carried him over deserts and mountains, until he arrived at Ethiopia, the kingdom of King Cepheus. Here he found the country filled with disastrous floods, towns and villages destroyed, and everywhere signs of devastation and ruin. On a projecting cliff close to the shore, he noticed a lovely maiden chained to a rock. This was Andromeda, the king’s daughter. Her mother Cassiopeia, having boasted that her beauty surpassed that of the Nereides, caused the angry sea-nymphs to appeal to Poseidon to retaliate, and thus the sea-god devastated the country with terrible waves, which brought with it a huge monster who consumed all that came in his way.

In their distress, the unfortunate Ethiopians begged the oracle of Zeus, Ammon, in the Libyan desert, and received the response that only by the sacrifice of the king’s daughter to the monster could the country and people be saved.

Cepheus, who fondly loved his dear daughter Andromeda, at first refused to listen to this dreadful proposal; but overcome at length by the prayers and begging of his unhappy citizens, the heartbroken father gave up his child for the welfare of his country. Andromeda was then chained to a rock on the seashore to serve as a prey to the monster, while her unhappy parents watched her sad fate on the beach below.

On being informed of the meaning of this tragic scene, Perseus proposed to Cepheus to kill the monster, on condition that the lovely victim should become his bride. Overjoyed at the possibility of Andromeda’s release, the king gladly accepted, and Perseus raced to the rock, to breathe words of hope and comfort to the frightened girl. Then putting on once more the helmet of Hades, he jumped into the air and waited for the approach of the monster.

The sea opened, and the shark’s head of the gigantic beast raised itself above the waves. Lashing his tail furiously from side to side, he leaped forward to bite his victim; but the courageous hero, watching his opportunity, suddenly darted down, and bringing out the head of the Medusa from his bag held it before the eyes of the dragon, whose hideous body became gradually transformed into a huge black rock. Perseus then unchained Andromeda and led her to her now happy parents, who, anxious to show their gratitude, ordered immediate preparations to be made for the marriage feast.

Perseus then left the Ethiopian king, and, accompanied by his beautiful bride, returned to Seriphus, where Perseus returned to give King Polydectes the “gift” he requested. When he did not find his mother in his court, and Polydectes would not reveal where she was, Perseus pulled out Medusa’s head from the bag. Polydectes revealed that he locked her in a dungeon, just before his mouth and whole head turned to stone.

After he rescued his mother, he then sent a messenger to his grandfather, informing him that he intended to return to Argos; but Acrisius, fearing the fulfillment of the oracle’s prophecy, fled for protection to his friend Teutemias, king of Larissa. Anxious to return to Argos, Perseus followed him. But here a strange accident occurred. While taking part in some funeral games, celebrated in honor of the king’s father, Perseus, by an unfortunate throw of the discus, accidentally struck his grandfather, and thereby was the innocent cause of his death.

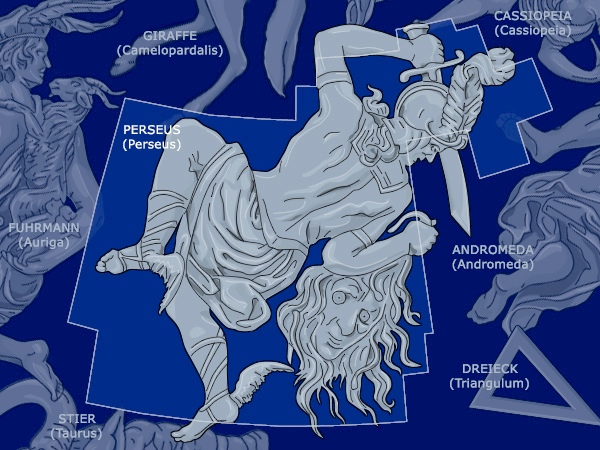

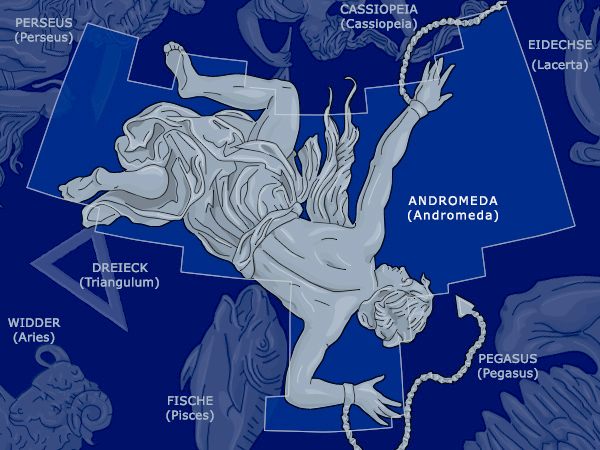

After celebrating the funeral rites of Acrisius, Perseus presented the head of the Medusa to his divine protector Athena, who placed it in the center of her shield. Later on, as happens to demi-gods, when Perseus’ mortal half died, he was taken up to the heavens and became a constellation, and afterwards Andromeda was also taken to the sky to shine near his stars, along with her mother, Cassiopeia.

|  |

Comprehension Questions

Answer the following questions according to the story.

- How was Perseus conceived?

- Why did Acrisius want to get rid of Perseus? How does he do that?

- Who raised Perseus?

- What three cool items did the Hesperides, Athena, and Hermes give Perseus?

- What is a Pegasus and how was it born?

- According to this story, how did the Red Sea get its name? Where is the Red Sea located currently?

- What did Perseus do with Medusa’s head at the end of the story?

- What happened to Acrisius? Why is this “ironic”?

- What happened to Perseus and Andromeda when they died?

- How many times did Perseus use the head of Medusa as a weapon?

Did you know?

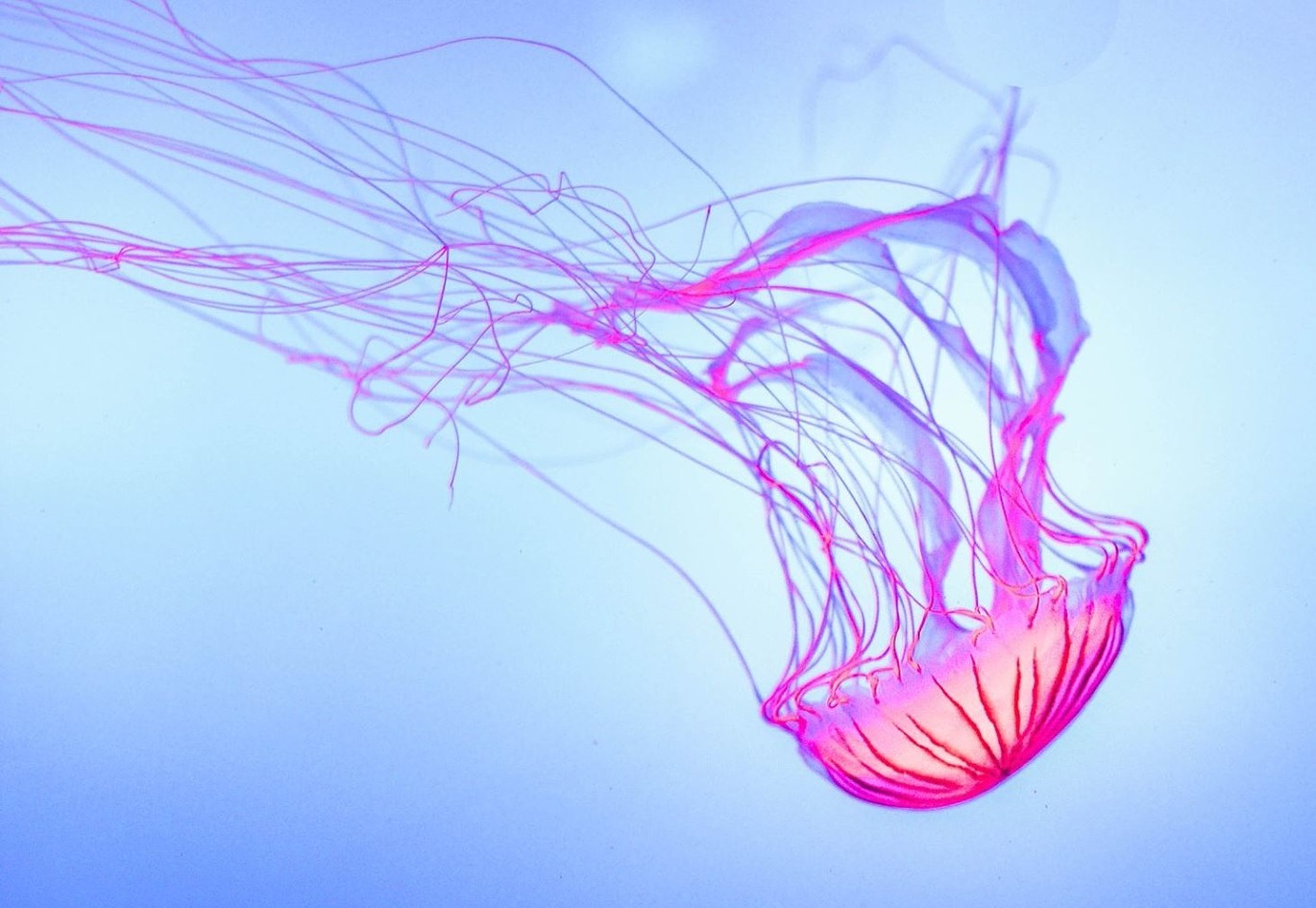

Medusa and Pegasus are two of the most well-known creatures from Greek mythology. Pegasus can be found on many transportation company logos. Medusa jellyfish have very long and poisonous tentacles that resemble Medusa’s snake hair.

Comprehension and Critical Thinking Questions

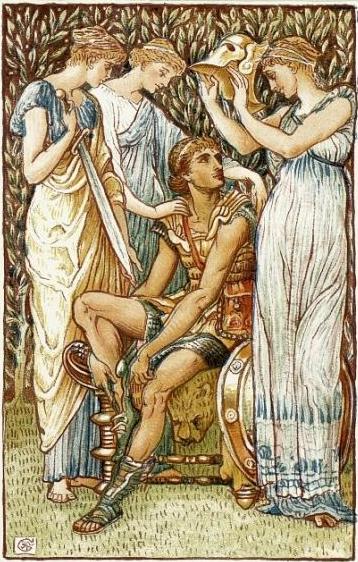

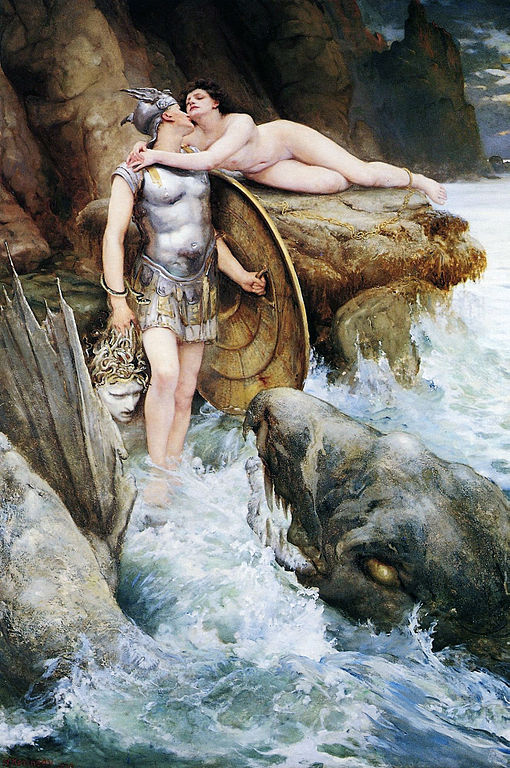

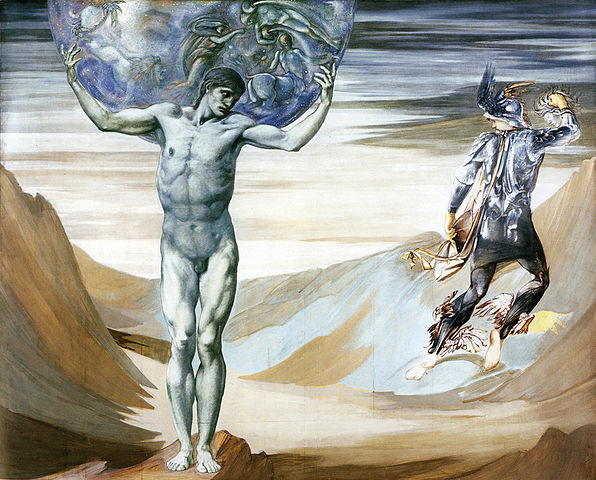

Who are the characters in the pictures below from the story of Perseus? Which event from the story is happening in each picture?

A |  B |

C |  D |

E |  F |

CEFR Level: CEF Level C1

- Image credits: A and B: by Walter Crane, 1892, $\ccpd$, C: by Charles Napier Kennedy, 1890, $\ccpd$, D: photo by Ohad Ben-Yoseph on Flickr, 2006, $\ccbyncnd$, E: Edward Burne-Jones, 1878, $\ccpd$ F: by Giorgio Ghisi (1520–1582) , $\ccpd$ ↵