Race in the Ancient World: Herodotus (Global survey format)

- Last updated

- Aug 11, 2021

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 116694

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

Race in the Ancient World: Herodotus

Who was Herodotus?

Herodotus was born in Halicarnassus, a Greek city on the coast of modern-day Turkey, in about 484 BCE. He was exiled for a period of time, in which he traveled around the Mediterranean world. Herodotus then returned briefly to Halicarnassus before leaving for a new Athenian colony in Italy. He often wrote about wars between the Persians and Greek-speaking city-states in 490 and 480 BCE, and had personal experience with the later Peloponnesian War, which was fought between Athens and Sparta during his lifetime.

Map of the world before the Peloponnesian wars, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons, from E. Lévy, La Grèce au Ve siècle (Paris, 1995).

Father of History or Father of Lies?

Herodotus is often credited with inventing the western tradition of history-writing. Yet he was criticized a generation later by Thucydides, another Greek historian, for including “mythical” and fantastical elements in his writing. Herodotus did not conform to Thucydides’ definition of what deserved to be included in a history: politics, economics, war and diplomacy. Instead he observed widely, writing on geography, natural history, religious and sexual practices, and more. Herodotus deliberately recorded what he heard from others, sometimes from multiple sources, leaving the reader (both then as now) to decide whether and which sources to believe.

Herodotus and Race

Before you begin the questions and reading, a note on race in Ancient Greek culture is necessary. The Greeks did not "see" race or ethnic group the way we do today. Unlike the modern era, ideas of "race" in Ancient Greece were based less on skin color or physical appearance, and more on which cultural practices or region a person was from. The Greeks considered the Phoenicians, for example, as a different ethnicity (because their language was not Greek), while the Spartans, despite their many wars with Athens, shared the same language and were thus labeled Greek. These “racial” lines were considered strengthened by descent from a common ancestor (often a mythical figure like Zeus, Poseidon, or a hero such as Theseus) and ties were further strengthened by marriage alliances.

Although the various Greek-speaking peoples acknowledged their differences, they stood united against other peoples who they considered “uncivilized.” When the Greeks did not understand a people or their culture, they would lump them together as a group and attribute specific marks of foreignness to them. In some cases these marks were small, such as magic using certain herbs, or the usage of different dyes in clothing or food products. However, in other cases the attributions could be more extreme. The centaurs, for example, are often thought to represent unfamiliar barbarian tribes in Greek artwork and legends. Similarly, the mythical Amazons, thought to be a race of men-hating female warriors, may have served as a distorted reflection of the Scythians, one of various tribal confederations that inhabited central Asia.

These ideas would have been familiar to Herodotus. He wrote specifically about wars between the Greek city-states (distinct groups that were nonetheless all considered "Greek") and the Persians (non-Greeks and thus a different race), yet his time in an Athenian colony in Asia Minor would have exposed him to these ideas. In his writings Herodotus often records testimony from other Greek travelers to those lands - people who would have most likely held similar concepts about race and other cultures.

What Do I Do When I Read These Passages?

Ask yourself the following questions as you read your assigned section(s) and be prepared to discuss them with your assigned group.

1. Why and how is Herodotus describing these groups for Greek audiences? What implied rating system does he use for each culture?

2. What makes a culture “civilized” according to Herodotus? What makes it not “civilized”?

3. What part do gender roles play in Herodotus’ ratings of civilizations? Why do you think this is an important issue for him?

4. How do climate, geography, and neighboring cultures shape a civilization? Which is more important, according to Herodotus?

5. Are there any achievements of these cultures Herodotus finds worthy of praise? What are they?

6. What have we just learned about how one ancient Greek author viewed other cultures? Has that changed our conception about “Greek” culture and what it has come to stand for? What does Greek culture stand for in Herodotus’ time? In ours?

7. How do Herodotus' descriptions of your culture compare to the depiction of that culture in the artwork attached to your section? Feel free to search the internet for more information on your artwork.

8. Do modern individuals have their own implied rating systems for cultures they encounter? What are these implied standards by which we judge other cultures and how do they compare to the standards used by Herodotus?

What world according to Herodotus may have looked like (5th century BC), courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Persia

I.132. To these gods the Persians offer sacrifice in the following manner: they raise no altar, light no fire, pour no libations; there is no sound of the flute, no putting on of chaplets, no consecrated barley-cake; but the man who wishes to sacrifice brings his victim to a spot of ground which is pure from pollution, and there calls upon the name of the god to whom he intends to offer. It is usual to have the turban encircled with a wreath, most commonly of myrtle. The sacrificer is not allowed to pray for blessings on himself alone, but he prays for the welfare of the king and of the whole Persian people, among whom he is of necessity included. He cuts the victim in pieces, and having boiled the flesh, he lays it out on the tenderest plants he can find, trefoil especially. When all is ready, one of the Magi comes forward and chants a hymn, which they say recounts the origin of the gods. It is not lawful to offer sacrifice unless there is a Magus present. After waiting a short time the sacrificer carries the flesh of the victim away with him and makes whatever use of it he may please.

Drawing of details from the Darius Painter, Darius Vase, 340-320 BCE, Archaeological Museum of Naples, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Libya

IV.168. The Libyans dwell in the order which I will now describe. Beginning on the side of Egypt, the first Libyans are the Adyrmachidæ. These people have, in most points, the same customs as the Egyptians, but use the costume of the Libyans. Their women wear on each leg a ring made of bronze, they let their hair grow long, and when they catch any vermin on their persons, bite it and throw it away. In this they differ from all the other Libyans. They are also the only tribe with whom the custom obtains of bringing all women about to become brides before the king, that he may choose such as are agreeable to him. The Adyrmachidæ extend from the borders of Egypt to the harbour called Port Plynus.

IV.190. All the wandering tribes bury their dead according to the fashion of the Greeks, except the Nasamonians. They bury them sitting, and are right careful when the sick man is at the point of giving up the ghost, to make him sit and not let him die lying down. The dwellings of these people are made of the stems of the asphodel, and of rushes wattled together. They can be carried from place to place. Such are the customs of the afore-mentioned tribes.

Click here for images of Libyans in Egyptian Art.

Egypt

II.12. Thus I give credit to those from whom I received this account of Egypt, and am myself, moreover, strongly of the same opinion, since I remarked that the country projects into the sea further than the neighboring shores, and I observed that there were shells upon the hills, and that salt exuded from the soil to such an extent as even to injure the pyramids; and I noticed also that there is but a single hill in all Egypt where sand is found, namely, the hill above Memphis; and further, I found the country to bear no resemblance either to its border-land, Arabia, or to Libya—nay, nor even to Syria, which forms the seaboard of Arabia; but whereas the soil of Libya is, we know, sandy and of a reddish hue, and that of Arabia and Syria inclines to stone and clay, Egypt has a soil that is black and crumbly, as being alluvial and formed of the deposits brought down by the river from Ethiopia.

II.36. In other countries the priests have long hair, in Egypt their heads are shaven; elsewhere it is customary, in mourning, for near relations to cut their hair close; the Egyptians, who wear no hair at any other time, when they lose a relative, let their beards and the hair of their heads grow long. All other men pass their lives separate from animals, the Egyptians have animals always living with them; others make barley and wheat their food; it is a disgrace to do so in Egypt, where the grain they live on is spelt, which some call zea. Dough they knead with their feet; but they mix mud, and even take up dirt, with their hands. They are the only people in the world—they at least, and such as have learnt the practice from them—who use circumcision. Their men wear two garments apiece, their women but one. They put on the rings and fasten the ropes to sails inside; others put them outside. When they write or calculate, instead of going, like the Greeks, from left to right, they move their hand from right to left; and they insist, notwithstanding, that it is they who go to the right, and the Greeks who go to the left. They have two quite different kinds of writing, one of which is called sacred, the other common.

II.37. They are religious to excess, far beyond any other race of men, and use the following ceremonies: They drink out of brazen cups, which they scour every day: there is no exception to this practice. They wear linen garments, which they are specially careful to have always fresh washed. They practise circumcision for the sake of cleanliness, considering it better to be cleanly than comely. The priests shave their whole body every other day, that no lice or other impure thing may adhere to them when they are engaged in the service of the gods. Their dress is entirely of linen, and their shoes of the papyrus plant: it is not lawful for them to wear either dress or shoes of any other material. They bathe twice every day in cold water, and twice each night; besides which they observe, so to speak, thousands of ceremonies. They enjoy, however, not a few advantages. They consume none of their own property, and are at no expense for anything; but every day bread is baked for them of the sacred corn, and a plentiful supply of beef and of goose’s flesh is assigned to each, and also a portion of wine made from the grape. Fish they are not allowed to eat; and beans,—which none of the Egyptians ever sow, or eat, if they come up of their own accord, either raw or boiled—the priests will not even endure to look on, since they consider it an unclean kind of pulse. Instead of a single priest, each god has the attendance of a college, at the head of which is a chief priest; when one of these dies, his son is appointed in his room.

II.85. The following is the way in which they conduct their mournings, and their funerals: On the death in any house of a man of consequence, forthwith the women of the family plaster their heads, and sometimes even their faces, with mud; and then, leaving the body indoors, sally forth and wander through the city, with their dress fastened by a band, and their bosoms bare, beating themselves as they walk. All the female relations join them and do the same. The men too, similarly begirt, beat their breasts separately. When these ceremonies are over, the body is carried away to be embalmed.

Click here for Greek depictions of Hercules (Heracles) in Egypt.

India, and the Ends of the Earth

III.99. Eastward of these Indians are another tribe, called Padæans, who are wanderers, and live on raw flesh. This tribe is said to have the following customs: If one of their number be ill, man or woman, they take the sick person, and if he be a man, the men of his acquaintance proceed to put him to death, because, they say, his flesh would be spoilt for them if he pined and wasted away with sickness. The man protests he is not ill in the least; but his friends will not accept his denial—in spite of all he can say, they kill him, and feast themselves on his body. So also if a woman be sick, the women, who are her friends, take her and do with her exactly the same as the men. If one of them reaches to old age, about which there is seldom any question, as commonly before that time they have had some disease or other, and so have been put to death—but if a man, notwithstanding, comes to be old, then they offer him in sacrifice to their gods, and afterwards eat his flesh.

106. It seems as if the extreme regions of the earth were blessed by nature with the most excellent productions, just in the same way that Greece enjoys a climate more excellently tempered than any other country. In India, which, as I observed lately, is the furthest region of the inhabited world towards the east, all the four-footed beasts and the birds are very much bigger than those found elsewhere, except only the horses, which are surpassed by the Median breed called the Nisæan. Gold too is produced there in vast abundance, some dug from the earth, some washed down by the rivers, some carried off in the mode which I have but now described. And further, there are trees which grow wild there, the fruit whereof is a wool exceeding in beauty and goodness that of sheep. The natives make their clothes of this tree-wool.

Drinking scene, with Dionysus and Ariadne on his lap, Greek drinking cups, Greek dress, Greco-Buddhist art of Adarna (India), dated 3rd century CE, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

The Black Sea Region: Scythia and its Neighbors (part 1)

I.216. The following are some of their customs. Each man has but one wife, yet all the wives are held in common; for this is a custom of the Massagetae and not of the Scythians, as the Greeks wrongly say. Human life does not come to its natural close with this people; but when a man grows very old, all his kinsfolk collect together and offer him up in sacrifice; offering at the same time some cattle also. After the sacrifice they boil the flesh and feast on it. Those who thus end their days are reckoned the happiest. If a man dies of disease they do not eat him, but bury him in the ground, bewailing his ill-fortune that he did not come to be sacrificed. They sow no grain, but live on their herds and on fish, of which there is great plenty in the Araxes. Milk is what they chiefly drink. The only god they worship is the sun, and to him they offer the horse in sacrifice; under the notion of giving to the swiftest of the gods the swiftest of all mortal creatures.

IV.23. As far as their country, the tract of land whereof I have been speaking is all a smooth plain, and the soil deep; beyond you enter on a region which is rugged and stony. Passing over a great extent of this rough country, you come to a people dwelling at the foot of lofty mountains, who are said to be all- both men and women- bald from their birth, to have flat noses, and very long chins. These people speak a language of their own,. the dress which they wear is the same as the Scythian. They live on the fruit of a certain tree, the name of which is Ponticum; in size it is about equal to our fig-tree, and it bears a fruit like a bean, with a stone inside. When the fruit is ripe, they strain it through cloths; the juice which runs off is black and thick, and is called by the natives "aschy." They lap this up with their tongues, and also mix it with milk for a drink; while they make the lees, which are solid, into cakes, and eat them instead of meat; for they have but few sheep in their country, in which there is no good pasturage. Each of them dwells under a tree, and they cover the tree in winter with a cloth of thick white felt, but take off the covering in the summer-time. No one harms these people, for they are looked upon as sacred- they do not even possess any warlike weapons. When their neighbours fall out, they make up the quarrel; and when one flies to them for refuge, he is safe from all hurt. They are called the Argippaeans.

IV.26. The Issedonians are said to have the following customs. When a man's father dies, all the near relatives bring sheep to the house; which are sacrificed, and their flesh cut in pieces, while at the same time the dead body undergoes the like treatment. The two sorts of flesh are afterwards mixed together, and the whole is served up at a banquet. The head of the dead man is treated differently: it is stripped bare, cleansed, and set in gold. It then becomes an ornament on which they pride themselves, and is brought out year by year at the great festival which sons keep in honor of their fathers' death, just as the Greeks keep their Genesia. In other respects the Issedonians are reputed to be observers of justice: and it is to be remarked that their women have equal authority with the men. Thus our knowledge extends as far as this nation.

IV.46. The Euxine sea, where Darius now went to war, has nations dwelling around it, with the one exception of the Scythians, more unpolished than those of any other region that we know of. For, setting aside Anacharsis and the Scythian people, there is not within this region a single nation which can be put forward as having any claims to wisdom, or which has produced a single person of any high repute. The Scythians indeed have in one respect, and that the very most important of all those that fall under man's control, shown themselves wiser than any nation upon the face of the earth. Their customs otherwise are not such as I admire. The one thing of which I speak is the contrivance whereby they make it impossible for the enemy who invades them to escape destruction, while they themselves are entirely out of his reach, unless it please them to engage with him. Having neither cities nor forts, and carrying their dwellings with them wherever they go; accustomed, moreover, one and all of them, to shoot from horseback; and living not by husbandry but on their cattle, their wagons the only houses that they possess, how can they fail of being unconquerable, and unassailable even?

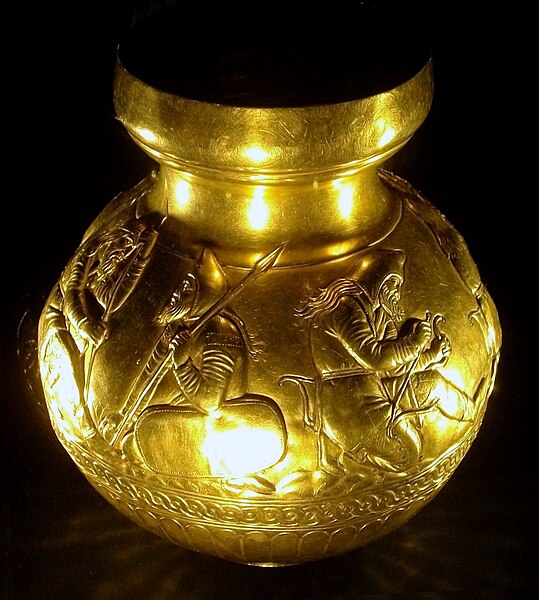

Electrum vase from the Kul-Oba kurgan, 2nd half of 4th century BCE. Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

The Black Sea Region: Scythia and its Neighbors (Part 2)

IV.59. Thus abundantly are the Scythians provided with the most important necessaries. Their manners and customs come now to be described. They worship only the following gods, namely, Vesta, whom they reverence beyond all the rest, Jupiter, and Tellus, whom they consider to be the wife of Jupiter; and after these Apollo, Celestial Venus, Hercules, and Mars. These gods are worshipped by the whole nation: the Royal Scythians offer sacrifice likewise to Neptune. In the Scythic tongue Vesta is called Tabiti, Jupiter (very properly, in my judgment) Papaeus, Tellus Apia, Apollo Oetosyrus, Celestial Venus Artimpasa, and Neptune Thamimasadas. They use no images, altars, or temples, except in the worship of Mars; but in his worship they do use them.

IV.104. The Agathyrsi are a race of men very luxurious, and very fond of wearing gold on their persons. They have wives in common, so that they may be all brothers, and, as members of one family, may neither envy nor hate one another. In other respects their customs approach nearly to those of the Thracians.

IV.117. The Sauromatæ speak the language of Scythia, but have never spoken it correctly, because the Amazons learnt it imperfectly from the first. Their marriage-law lays it down that no girl shall wed till she has killed a man in battle. Sometimes it happens that a woman dies unmarried at an advanced age, having never been able in her whole lifetime to fulfill the condition.

A Scythian gold comb, Soloha kurgan, Hermitage museum, St. Petersburg, Russia, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Thracians

V.6. The Thracians who do not belong to these tribes have the customs which follow. They sell their children to traders. On their maidens they keep no watch, but leave them altogether free, while on the conduct of their wives they keep a most strict watch. Brides are purchased off their parents for large sums of money. Tattooing among them marks noble birth, and the want of it low birth. To be idle is accounted the most honorable thing, and to be a tiller of the ground the most dishonourable. To live by war and plunder is of all things the most glorious. These are the most remarkable of their customs.

V.7. The gods which they worship are but three, Mars, Bacchus, and Diana. Their kings, however, unlike the rest of the citizens, worship Mercury more than any other god, always swearing by his name, and declaring that they are themselves sprung from him.

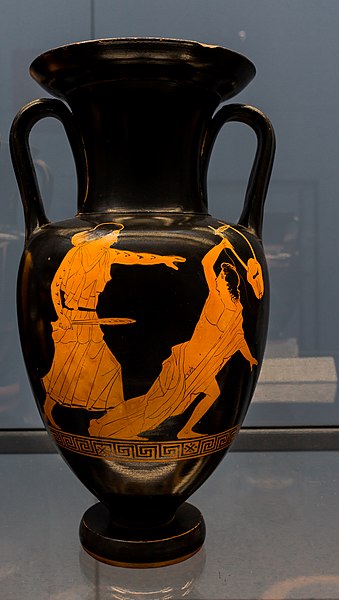

Phiale Painter, attic red figure "Nolan" neck-amphora, side A: Thracian woman with sword killing Orpheus who tries to defend himself with his lyre, Staatliche Antikensammlungen, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.