14.5: Nobuo Uematsu and Final Fantasy VI

- Page ID

- 172190

Nobuo Uematsu and Final Fantasy VI.

Born in 1959 in Kouchi City, Japan, Nobuo Uematsu is one of the most celebrated composers in video game music. Though he had no formal musical training, he has enjoyed an incredibly successful career as a composer for video games. He has been compared to Beethoven, John Williams, and Richard Wagner alike—and with good reason! His developmental techniques are similar to Beethoven, and his use of the leitmotif is similar to that of Wagner and Williams.

Born in 1959 in Kouchi City, Japan, Nobuo Uematsu is one of the most celebrated composers in video game music. Though he had no formal musical training, he has enjoyed an incredibly successful career as a composer for video games. He has been compared to Beethoven, John Williams, and Richard Wagner alike—and with good reason! His developmental techniques are similar to Beethoven, and his use of the leitmotif is similar to that of Wagner and Williams.

Uematsu began working as a composer for game developer Square in 1986, though it was mostly a side job for him. Square's first games are relatively unknown in the West, as the majority of them have never been ported to the West. Soundtracks to games like Cruise Chaser Blassty, Alpha, King's Knight, GEnesis: Beyond the Revelation, and Cleopatra no Maho were all composed within 1986-1987. His "big break" came with the game Final Fantasy, released in Japan in 1987 and created by Hironobu Sakaguchi. The game's popularity was so successful that the title is now on the 16th installment for the PlayStation 5. The game has also spawned dozens of spinoffs, remasters, reboots, and remakes.

Uematsu's soundrack to the original 8-bit Final Fantasy was fairly complex, simple as it may have sounded. He composed different types of music for different scenes: peaceful music accompanied players as they visted towns, rock music accompanied their battles, heroic music accompanied players' traversing of the world map, and tense music accompanied them as they traveled through dungeons. Though the music was short and limited, it provided the foundation for what would come next in the 16-bit era.

Beginning with Super Nintendo's 1991 release of Final Fantasy IV (originally released in the West as Final Fantasy II), Uematsu's soundtracks became much more involved. Similar to film, he began incorporating recurring main themes that mostly represented the cast of protagonists (or the leading protagonist) that would change according to the setting. (This is similar to Koji Kondo's technique in Super Mario World). He also provided the majority of main characters their own character themes, as one would expect in film. These themes leitmotivically interact with one another, as well as the unfolding drama—as one would expect—while also interacting with the player's decision-making, as was discussed a few pages ago. In othe words, these leitmotifs act both cinematically and ludically (ludic being the Latin word for "play.")

(above): picture of Nobuo Uematsu. Taken from Hafabramusic.com, fair use under US law.

Final Fantasy VI.

Box art to Final Fantasy VI. From Wikipedia; fair use under US law.

Final Fantasy VI was released in 1994 and was the last FF game to be released for the Super Nintendo. The game consists of 14 heroes and several villains, each represented by their own character themes. This soundtrack demonstrates Uematsu's subtle approach to composition and leitmotivic scoring. Characters' outward personalities are mostly represented in their character themes, while some of them have different transformations that tell their complex backstory, all of which are rooted in some type of tragedy or trauma. Moreover, many themes are all connected through small motivic gestures. This subtle way of connecting different themes is similar to Howard Shore's approach to Fellowship of the Rings soundtrack, though Uematsu's soundtrack predates Shore's soundtrack by almost a decade!

The game's plot resembles a Star Wars story: an evil empire hellbent on world domination is resisted by a small group of rebels called the Returners. Players meet 14 characters, each with their own personal backstory involving tragedy induced by the Empire in some way; this bond of tragedy strengthens their cause to defeat the Empire. As in film, each of these characters have their own leitmotifs that sound when they're on screen, or when they're referred to. Here, we'll look at the musical representation surrounding Locke Cole, one of the many heroes of the story.

Heroism and Tragedy in Locke Cole's Leitmotif.

(left): Locke's first appearance, accompanied by his heroic "Locke's Theme" (screenshot from YouTube)

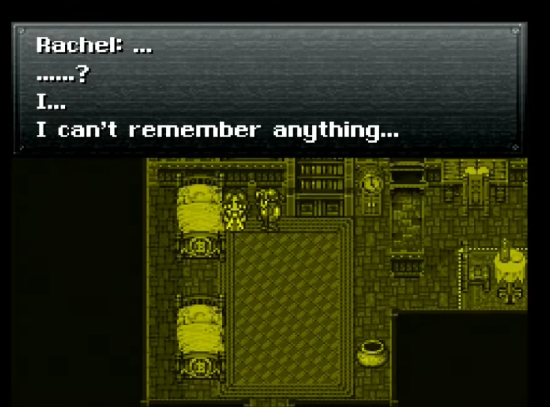

(right): Locke recalls his past that depicts his fiancé's tragedy, accompanied by the mournful transformation of his theme called "Forever Rachel" (screenshot from YouTube)

Locke Cole is a treasure hunter with a charming and optimistic outward personality. As a result, his character theme bears all of the markers of heroism, using many characteristics of the march topics and fanfare topic (recall from the earlier video presentation that when composers combine the march with the fanfare, we get a hero topic). When we first meet Locke, he comes to the aid of the rebellion to help rescue one of their newest allies. Snare drums, brass fanfares, bright harmonies, and large melodic skips all impart the sense of optimism and hear his theme plays proudly, confirming his identity as one of many heroes within the game. Watch this video of Locke's introduction into the game: his character theme (named "Locke's Theme") plays heroically in the background. Locke's theme follows a very specific musical form of |:A, A, [transition] B:|. The symbols " |: :|" means "repeat." In other words, as you listen to "Locke's Theme," you'll hear an A section played twice, followed by a short transition (or "bridge"), and then a B section before the entire track loops back and repeats. Pay attention to the form as you listen to Locke's theme, and especially pay attention to the "B section." (If it's difficult to follow, don't worry, because the video presentation for this track covers these sections in more detail).

We later find out in the game that Locke has a tragic history that he cannot escape: years earlier, while adventuring through caves with his fiancé Rachel, she fell off a bridge and slipped into a coma; when she recovered, she had lost her memory, causing her family to disown him. While he searched the world trying to find a cure for her amnesia, her village was torched by the Empire. As Locke recalls his tragic history, we hear "Forever Rachel," the same melody as "Locke's Theme," but played in more of a melancholic tone. The march topic and fanfares are gone, and the melody is played mournfully in the minor mode by an oboe. Watch this video of Locke as he recalls the traumatic event that caused all of his hardship. Pay close attention to the emotional affect imparted by this transformation of an otherwise heroic and optimistic melody.

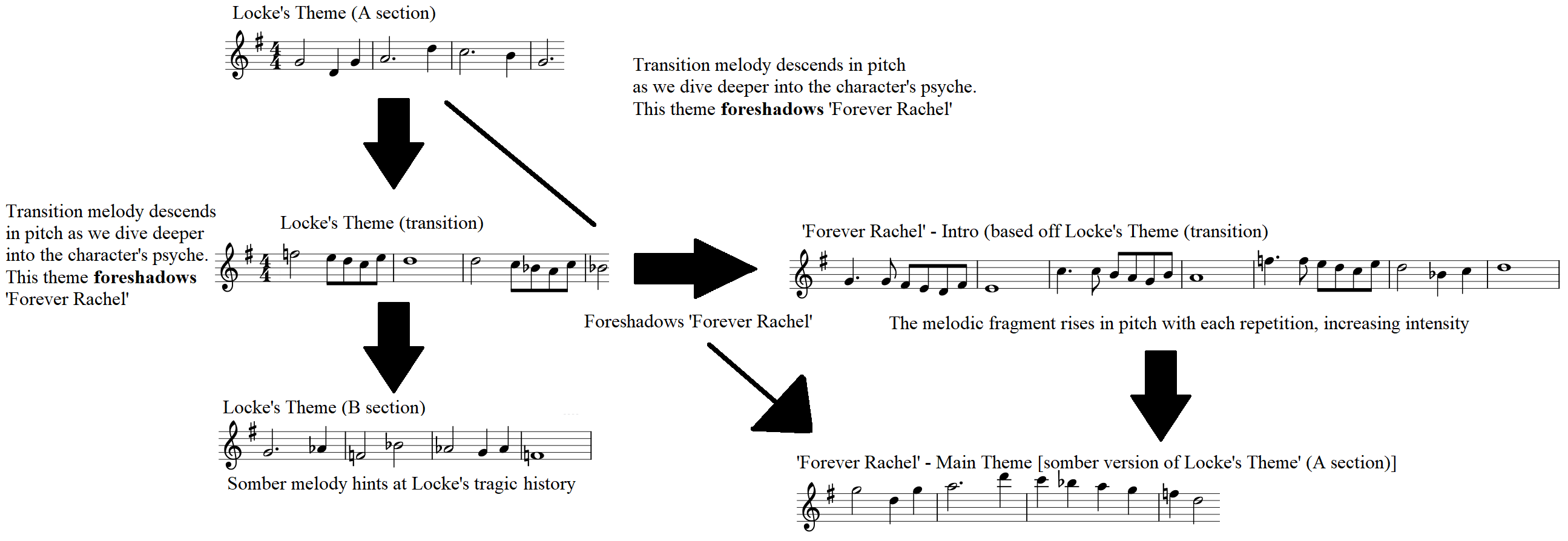

What's more is that Locke's tragedy is musically foreshadowed in his own heroic theme: a short melodic passage within the music's B section foreshadows the introduction of "Forever Rachel," though we only hear it briefly and subtly: as the diagram below demonstrates, the A section to Locke's Theme moves into a brief transition, which is the exact material used as the introduction to "Forever Rachel," which then moves into the A section of Locke's Theme, only played in a mournful tone!

What's even more astounding is that the B section of "Locke's Theme" is found in multiple character themes and other music within the soundtrack. Considering that every character in the game has a tragic backstory, it's like Uematsu tells us that each character is indeed linked by tragedy, using the "B section" as the musical link.

Watch the video presentation that covers the character themes of Locke, the Figaro brothers, and Cyan. Each character's theme endures the same type of transformation as Locke's theme does, and each theme does indeed contain the same "B section" material from Locke's theme!

Diagram showing the musical anatomy of "Locke's Theme."

Musical Topics in the Villain's Theme: Kefka Palazzo

Kefka's introduction in Final Fantasy VI, accompanied by his own theme, "Kefka." (Screenshot taken from YouTube).

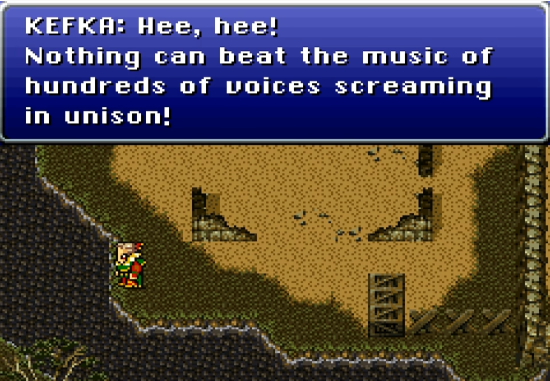

Although Final Fantasy VI begins as a "Star Wars Story," the plot develops outside of that fairly quickly. Emperor Gestahl is initially set up to the be main villain of the game; his second-in-command, Kefka Palazzo, although initially set up to be almost a comic relief villain: he's dressed as an evil clown as he treads through the desert to deliver an ultimatum to one of the Rebellion's allies. His outward demeanor and his musical theme (simply called "Kefka") does nothing to inspire fear or respect. Set in the march style, Uematsu favors high winds and minimal instrumental accompaniment, creating a very thin texture. The result is a comically unthreatening villain's tune: watch this clip of Kefka's initial appearance in the game and you'll get a sense that although he may not be a "good guy," he certainly poses no true threat.

As the story progresses, players learn how evil Kefka truly is. He poisons the entire city of Doma including his own soldiers, and eventually murders the Emperor to absorb the magical abilities housed by the three Statues of the Warring Triad (pictured below). Watch these two scenes, paying close attnetion to the musical accompaniment: during the poisoning of Doma, we hear his light-hearted leitmotif, suggesting that Kefka actually derives pleasure from his crimes. During the scene where we witness Kefka murdering the emperor, we hear another track called "Catastrophe," which establishes a much darker tone, reflecting the weight of his actions.

(left): Kefka gleefully murders the people of Doma by poisonining their water supply (Screenshot taken from YouTube).

(right): Kefka murders his emperor and absorbs the magical abilities from the statues of the Warring Triad (Screenshot taken from YouTube).

The Final Battle: "Dancing Mad."

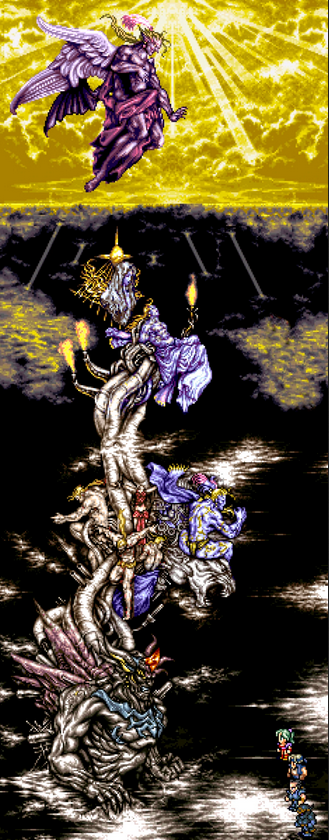

After killing the emperor, Kefka absorbs the magical power of the statues, becomes a demigod, and nearly destroys the entire planet, causing the heroes to scatter. Players must regroup their allies and finally confront Kefka and put an end to his madness. In this final battle, players must fight their way through the 3 statues one by one before finally reaching Kefka himself. As you can see in the picture to the left, players (in the far bottom right) must travel up one by one before reaching Kefka, who is adorned as a fallen angel.

After killing the emperor, Kefka absorbs the magical power of the statues, becomes a demigod, and nearly destroys the entire planet, causing the heroes to scatter. Players must regroup their allies and finally confront Kefka and put an end to his madness. In this final battle, players must fight their way through the 3 statues one by one before finally reaching Kefka himself. As you can see in the picture to the left, players (in the far bottom right) must travel up one by one before reaching Kefka, who is adorned as a fallen angel.

The picture from the left is taken from the actual gameplay, and is riddled with religious symbolism. Each statue from the bottom resembles a different stage of Dante's trilogy The Divine Comedy, which depicts the narrator traveling from Hell (Inferno), through Purgatory (Purgatorio), and then finally Heaven (Paradiso).

When examining the statues, we can see how the bottom statue resembles a devil or a demon with its red horns and claws, depicting the Inferno. The second statue contains human figures—one dressed in red looks like it resembles the crucifixion, and resembles Earth or perhaps Purgatory, the "halfway" point between our physical existence and Heaven according to traditional Catholic faith (according to the faith, sinners atone for their sins in Purgatory before moving to Heaven). The top statue resembles Christ and the Virgin Mary, adorned with wings and a halo, depicting Heaven, or Paradiso. Upon defeating the 3 statues, players then move to Kefka, who has become a perversion of God.

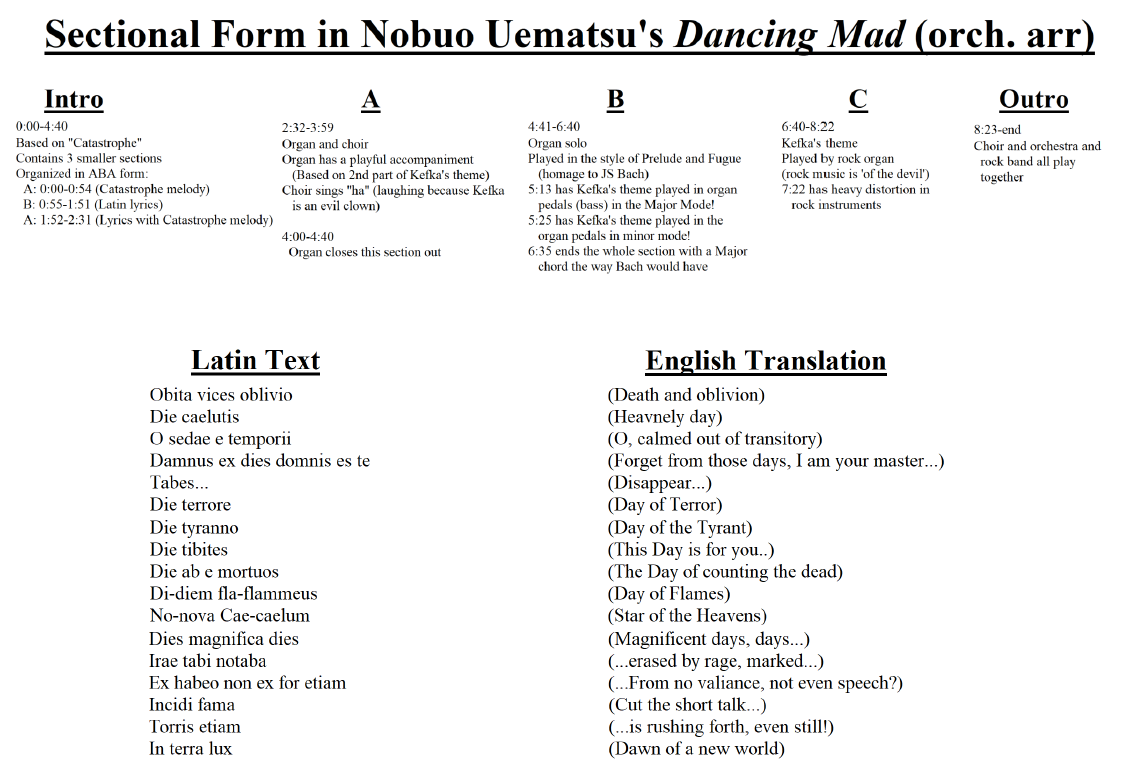

For the musical accompaniment to this piece, Nobuo Uematsu wrote a massive 17-minute long track consisting of 4 different sections, depicting the four different tiers of the of the battle. The music is called "Dancing Mad," perfectly befitting the madness that the villain exhibits. Here, Uematsu combines the religious topic (through the use of organ and choir) with the rock music topic, which incorporates electric guitar, drum kit, and lots of distortion. Because rock music has a traditionally rebellious aura about it, Uematsu musically suggests that the players are rebelling against this false god! Listen to "Dancing Mad," and follow along with the different timestamps of the various "tiers" (or sections) of the music:

Tier 1 (0:00-4:33). This music is based on his ‘Catastrophe,’ which was heard the first time Kefka destroyed the world. We hear electric organ and choir in this section, blending both the religious and rock topics as mentioned above.

Tier 2 (4:33-8:12). This is a silly-sounding march, based loosely off of Kefka’s leitmotif. All we hear is the church organ and the choir (synthesized, of course!). It almost sounds like the choir is laughing at the player!

Tier 3 (8:12-12:04). Hear, we hear an organ solo in the style of J.S. Bach. As you listen, pay attention to lowest notes -- you'll be able to hear a short fragment of Kefka's own theme!

Tier 4 (12:04-end) Here, we finally get Kefka’s leitmotif played in many different instruments with lots of rhythmic excitement.

When you're finished listening, listen to the fully-orchestrated performance of this same piece, played by live orchestra, rock band, and choir. The text was written in the Latin language to further reflect the religious topics. As you listen, follow along with the handout below on the music's form, which follows a structure that looks like "Intro, A, B, C, outro." In many respects, this music resembles the sectional form from the Romantic era (19th century). When you're done listening to the music, watch the video presentation on this unit for a more in-depth discussion on this character and his music.

(above): "Kefka's Tower" shared by Phead on DeviantArt.