12.2: Opera in the Baroque Period

- Page ID

- 165671

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Baroque Opera.

Probably the most important contribution to music and drama from the Baroque era (1600-1750) is the opera. Operas are staged dramas that are sung from beginning to end. Traditionally, they are on a very serious subject matter, very often a Greek tragedy. Operas as incredibly expensive to put together: singers, orchestras, set designers, costumes designers, lighting, music directors, and acting coaches all come together to put on a giant spectacle for an audience interested in music and drama. There are typically two different aspects of the opera: the libretto, which is the text (like a screenplay), is often written by someone other than the composer. Librettists often work with the composer, who sets the text to different types of music. The earliest opera that has survived comes from 1607: Monteverdi's Orpheus, which depicts the Greek tragedy of the Orpheus, a Greek poet and musician, whose wife Eurydice was killed by vipers. Orpheus sang the most mournful songs, which affected many of the Greek gods who took pity on him; they advised him to travel to the Underworld and retrieve her soul. Monteverdi's opera depicting Orpheus's journey helped set the stage for operas to come.

Probably the most important contribution to music and drama from the Baroque era (1600-1750) is the opera. Operas are staged dramas that are sung from beginning to end. Traditionally, they are on a very serious subject matter, very often a Greek tragedy. Operas as incredibly expensive to put together: singers, orchestras, set designers, costumes designers, lighting, music directors, and acting coaches all come together to put on a giant spectacle for an audience interested in music and drama. There are typically two different aspects of the opera: the libretto, which is the text (like a screenplay), is often written by someone other than the composer. Librettists often work with the composer, who sets the text to different types of music. The earliest opera that has survived comes from 1607: Monteverdi's Orpheus, which depicts the Greek tragedy of the Orpheus, a Greek poet and musician, whose wife Eurydice was killed by vipers. Orpheus sang the most mournful songs, which affected many of the Greek gods who took pity on him; they advised him to travel to the Underworld and retrieve her soul. Monteverdi's opera depicting Orpheus's journey helped set the stage for operas to come.

Similar to the cantata (recall Chapter 11.4) operas contain a number of different types of music:

Overture: a purely instrumental introduction to the entire opera. Because operas were seen as "social events," many people gathered and mingled before the performance. Overtures were typically a way to get people to take their seats to let them know that the performance was about to start. Unlike overtures in musical theater, overtures in the Baroque period did not play a "medley" of the important themes; it was typically just instrumental music that was unrelated to the music yet to come.

Arias. These are the more lyrical and more expressive type of song sung in an opera. It is with an aria where the characters often express their deepest emotions, similar to the soliloquy in a play, where a character takes center stage and gives a "speech" to the audience. Arias typically repeat the same text over and over, because the real focus of our attention is the music. The word aria translates to air, much of which is needed in order to sing these long lyrical melodies! Often, arias are homophonic in texture: that is, a single melody with instrumental accompaniment. This is done so that audiences can understand the text being sung.

Recitative. These songs are usually much shorter than arias, and are used to move the dialogue forward. Characters will converse with one another using recitatives, which translates to "recite" (as in, to recite one's lines). Because of this, the orchestra is used only sparingly, playing a few chords here and there, and the singers sound more like they're speaking than singing. Similar to arias, recitatives are typically homophonic in texture.

Choruses. In ancient Greek tragedies, there was often a Chorus, who would provide narration or commentary on the events unfolding. Unlike the aria and recitative, choruses often include polyphonic textures, allowing the composer to demonstrate their counterpoint skills.

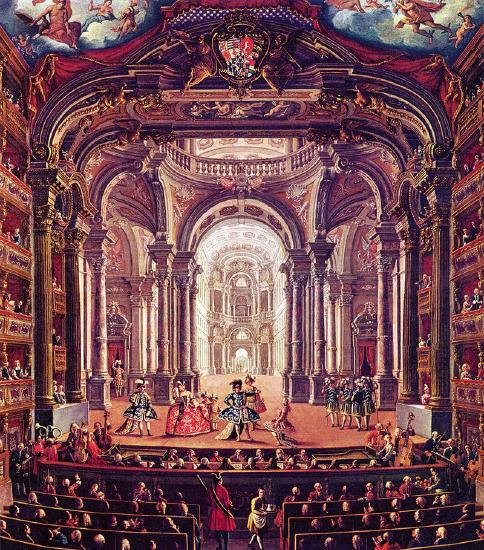

(above): 18th-century painting of the Royal Theatre of Turin (before its destruction and rebuilding), by Pietro Domenico Oliviero. Public Domain

Henry Purcell's Dido and Aeneas.

Portrait of Henry Purcell by John Closterman - [1], Public Domain.

Many operas in the Baroque Period were written in Italian, German, or French. The English public was fairly hostile toward opera in the 1600s because England had such a strong tradition in spoken theater (much in part due to Shakespeare). The opera we'll cover here is therefore an anomaly: Henry Purcell (1659-95) was an English composer who wrote only a single opera—Dido and Aeneas—but it is still considered one of the greatest Baroque operas to have survived. The story is rooted in Greek tragedy about Dido, the Queen of Carthage, Aeneas, a Trojan prince, and Belinda, Dido's maidservant. A very brief summary of the plot reads like this: following the events of the Trojan war, Aeneas fulfills a promise to the gods to travel to Italy to establish the city of Rome. They land in Carthage (the northern tip of Africa), where he meets and falls in love with Dido. Aeneas decides to abandon his plans of establishing Rome so he can marry Dido. A witch disguised as the messenger god Mercury, tricks Aeneas into leaving, which he does. In response to his abrupt departure, Dido commits suicide by drinking poison, but not before singing one of the most famous recitatives and arias of the Baroque literature, which as been referred to as "Dido's Lament."

Watch this video of Malena Erlman's phenomenal performance of "Dido's lament." You'll notice that the orchestra is very small: mostly strings and a harpsichord is all that accompanies the singers here.

The text is provided below (it is also sung in English). She begins with a recitative (seen below): notice how quickly she sings through this passage, as she tells Belinda that she is dying. The orchestra plays very little in this passage, and her speech is very syllabic. As soon as she's done with the recitative, she begins to sing the aria "When I am laid in earth." You'll notice how much more expressive this song is: she sings much more lyrically here, and she repeats the same line many times. After she dies, the chorus begins to sing a chorus, weeping that their Queen has died. When you're finished watching this scene, watch the video presentation that further highlights the various musical differences between the different types of songs in the opera.

Recitative (sung by Dido): Thy hand, Belinda... darkness shades me;

on thy bosom let me rest;

more I would, but Death invades me:

death is now a welcome guest!

Aria (sung by Dido) “When I am laid, am laid in earth,

may my wrongs create no trouble,

no trouble in thy breast

Remember me, but ah! Forget my fate”