8.4: Concertos in the Classical Era

- Page ID

- 165657

The Classical Concerto.

When we compare the concerto in the Classical Era (1750-~1820) to the Baroque Period (1600-1750), we see a similar evolution of size and form that we see when we compare the instrumental sonata in the two periods. The Classical Era concerto keeps the 3-movement "fast-slow-fast" structure that we see in the Baroque period, but the form of each individual movement is treated similarly to the instrumental sonata: the first movement is often in sonata form, the final movement is often in rondo form, and the middle movement is written in any form, as long as it's slow. As one would expect, the size of the orchestra is larger than it was in the Baroque Period. You'll notice that the harpsichord is no longer used, and the orchestra combines strings with woodwinds, brass, and some percussion as well.

All of the well-known composers of the Classical Era (Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven) composed concertos for a variety of instruments: flute, clarinet, violin, cello, piano---you name it, they wrote it! These pieces were not for amateurs, as mentioned in the previous pages. As a matter of fact, as the time periods progressed into the 19th and then 20th centuries, the music became more and more challenging for the performers. Composers often sought to push the limits of the performers. Often, composers would write their music with a specific soloist in mind, so they already knew what their soloist would be capable of.

The Expanded Sonata Form.

In addition to a larger orchestra, Classical Era composers treated the first movement's sonata form more expansively. Readers should re-familiarize themselves with sonata form before reading on.

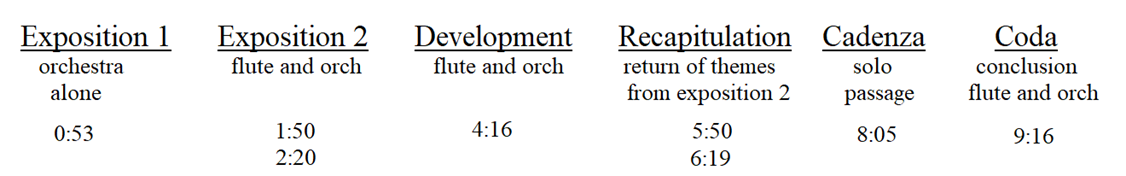

In the concerto's first movement's expanded sonata form, the entire orchestra typically plays the entire exposition without the soloist at all as an introduction. Then, the entire exposition is repeated, this time played primarily by the soloist. The exposition with the soloist is then repeated! This is referred to as the double exposition: Exposition 1 is played by the orchestra, and it is then repeated with the soloist performing the themes instead of the orchestra. Listen to the first 3 minutes of Mozart's flute concerto performed by Emmanual Pahud. You'll hear the orchestra introduce the flute by playing all of the exposition before the flute soloist even plays a single note. The flute will then enter and play all of the themes with the orchestra accompanying them.

After the 2nd exposition, the music moves into the development, as we would expect before returning to the Recapitulation. Instead of concluding the music, however, the recapitulation always leads to a cadenza: here, the entire orchestra drops out, and the soloist plays their own unaccompanied music, almost improvisationally --- sometimes up to 2 or 3 minutes before the orchestra joins back in, and brings the movement to a close.

Traditionally speaking, the soloist would actually write their own cadenza, but composers would write out a cadenza themselves when they published the music because not all performers are capable of writing their own music! Take a listen to the cadenza in Mozart's flute concerto: here, you'll hear the orchestra drop out entirely, while the flute player plays their own solo for over a minute before the orchestra joins back in.

The diagram below demonstrates the entire form of this 1st movement. As you listen to the entire piece, follow along with the diagram below and see if you can follow where you are in the in music. The time stamps below show where the large sections occur in the movement.

When you're finished, watch the video presentation on this piece, and you'll have a strong understanding of the music's overall form.