5.4: Chamber Music in the 19th and 20th Centuries

- Page ID

- 165604

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Chamber Music in the 19th and 20th Centuries.

This page covers chamber music in both the 19th and 20th centuries. When you're done reading through, watch the Video Presentation that covers some of these pieces and forms in more detail.

Romantic Era (19th century: ~1820-1900).

The term "Romantic" is often used to describe an artistic movement within the 19th century that emphasized individual expression, emotion, and storytelling within their instrumental music. Although it doesn't refer to all types of music in the 19th century, it was an important movement within the 19th century.

One of the most important characteristics of all music in the 19th century, regardless as to whether composers were considered 'Romantic' in style, was that the musical form got larger, longer, and more complex. Composers continued to write string quartets, piano trio, instrumental sonatas, and other types of "traditional" chamber music, but the music got longer and more complicated.

Other musical traits of the 19th century is that the music became more chromatic and composers embraced dissonance more freely. In simple terms, the music became in many ways, more intense for the listener -- possibly in an attempt to express emotions more effectively!

We will come across these traits of romanticism in much more detail in our unit on Piano Music and Programmatic Music. In the meantime, this unit will discuss in more detail the Woodwind Quintet, which was not truly established as a "sophisticated ensemble" until the 19th century thanks to two important composers: Franz Danzi and Anton Reicha.

Franz Danzi: The "Father of the Woodwind Quintet."

Although some composers in the Classical Era had combined wind instruments together in chamber music settings, the woodwind quintet did not fully become established as a "legitimate" ensemble for artistic purposes until the 19th century. German-born composer Franz Danzi (1763-1826) was one of the most important figures in helping establish the genre to the status of "high-art." Little has been written about the composer, and as his birth dates indicate, he died right at the beginning of the "Romantic Era," two and a half decades into the 19th century.

Traditionally speaking, woodwind instruments did not enjoy the same "high status" as string instruments. The reason for this is still debated to this day, but the odd reality is that woodwind music was not seen as "legitimate" art music compared to the string quartet. Danzi helped to challenge this notion, composing many works for winds throughout his entire career. All told, he wrote 9 woodwind quintets, each of which consisted either 3 or 4 movements. He also wrote several pieces called "Quintet for winds and Piano," which combined four wind players and a piano. He also wrote a woodwind sextet, as well as a large piece for wind quintet and orchestra.

He is perhaps best known for his woodwind quintets, however, which were just as sophisticated in terms of form as some of Beethoven's string quartets. The video presentation goes into extensive detail surrounding the last movement of his Quintet in G minor, op. 56. As youl listen, you should notice that you're able to hear each and every instrument very clearly, because each instrument produces sound in a different way! Readers may want to re-familiarize themselves with the chapter on Small Ensembles before watching this unit's video.

Portrait of Franz Danzi by Heinrich Eduard Winter. Public Domain.

Chamber Music in the 20th Century.

Music of the 20th century sounds very different from music in the Classical and 19th Century. Next chapter, you'll be exposed to many of the different artistic movements of the 20th century, and will learn what makes the music sound so different. Until then, we will look at a few chamber pieces from the 20th century, focusing our attention on musical style and instrumentation. Some composers of the 20th century continued to write for the traditional instrumental ensembles. Russian composers like Dmitri Shostakovich and Sergei Prokofiev composed many string quartets, instrumental sonatas, piano trio, and other "traditional" works. Their music sounded different from the periods that came before it because of the ways that they wrote melodies as well as their use of harmony, especially as it pertained to dissonance. Composers like Arnold Schoenberg, who you'll read about next chapter, also wrote many string quartets and piano trios. He also combined instruments that weren't typically combined; you'll see his piece Pierrot Lunaire next chapter.

In this unit, we'll compare two very different types of 20th century chamber music: a traditional ensemble by French composer, Olivier Messiaen, and a very non-traditional example by American composer George Crumb who had just passed away in 2022. As you listen to some of this music, you should be asking yourself what makes this music sound so unique, and what sets it apart from the other music you've been studying these past few units? Music of the 20th century often sounds foreign to us because it manipulates the melodic and harmonic idioms that we're used to in ways that sometimes confuse us!

Olivier Messiaen and Quartet for the End of Time.

.jpg?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=419&height=559) Olivier Messiaen (1908-1992) was a innovator. His music is known for its complex style: it contains radically dissonant sound, focusing primarily on color rather than the "rules" of harmony that had been established centuries ago in the Baroque Period. His music is incredibly challenging to perform, and sometimes difficult to listen to, especially for non-musicians (but even musicians find his music difficult to listen to!) He was very intersected in bird calls, and would often try to imitate bird songs in his music. He even wrote an extensive piece of music for solo piano titled Catalogue d'oiseaux, or Catlogue of Birds. He transcribed the bird calls as best he could, and incorporated them into his music! Take a listen to this video --- you'll hear actual bird songs, immediately followed by his own piano transcription of them. Not only did he write an entire 2-hour piano work that used these bird calls, but he would often insert these calls into his other music.

Olivier Messiaen (1908-1992) was a innovator. His music is known for its complex style: it contains radically dissonant sound, focusing primarily on color rather than the "rules" of harmony that had been established centuries ago in the Baroque Period. His music is incredibly challenging to perform, and sometimes difficult to listen to, especially for non-musicians (but even musicians find his music difficult to listen to!) He was very intersected in bird calls, and would often try to imitate bird songs in his music. He even wrote an extensive piece of music for solo piano titled Catalogue d'oiseaux, or Catlogue of Birds. He transcribed the bird calls as best he could, and incorporated them into his music! Take a listen to this video --- you'll hear actual bird songs, immediately followed by his own piano transcription of them. Not only did he write an entire 2-hour piano work that used these bird calls, but he would often insert these calls into his other music.

Oneo of his most celebrated works of chamber music is called Quartet for the End of Time, which he wrote while being held as a Prisoner of War in a German prison camp. Messiaen was drafted into the French army in World War II, and was sent to a Nazi prison camp in 1940. While imprisoned, he met several other musicians, for whom he would write his 50-minute work Quartet for the End of Time for an ensemble consisting of piano, violin, cello, and clarinet. Though this is a somewhat "odd" group of instruments to compose for (meaning non-traditional), these were the only instruments that were available to him during these circumstances, and so this is who he wrote for. A sympathetic prison guard was able to get him materials necessary to write the music down and get it to his performers. Upon completion, the musicians performed in front of about 400 prisoners and guards.

As a devout Catholic, Messiaen gathered inspiration from the Book of Revelation, the last book of the New Testament that depicts the End Times when Jesus returns to Earth. As prophesied in the Scriptures, he and God will judge the Living and the Dead where the righteous will be saved, and the others will be damned. According to his program notes (prose that are included with the music so that the audience understands the music better), the text "Quartet fo the End of Time" is taken from Revelation, 10:1–2, 5–7 from the King James Version:

"And I saw another mighty angel come down from heaven, clothed with a cloud: and a rainbow was upon his head, and his face was as it were the sun, and his feet as pillars of fire ... and he set his right foot upon the sea, and his left foot on the earth .... And the angel which I saw stand upon the sea and upon the earth lifted up his hand to heaven, and sware by him that liveth for ever and ever ... that there should be time no longer: But in the days of the voice of the seventh angel, when he shall begin to sound, the mystery of God should be finished..."

Years later, Messiaen would recall the performance at the prison camp:

Years later, Messiaen would recall the performance at the prison camp:

"The Stalag was buried in snow. We were 30,000 prisoners (French for the most part, with a few Poles and Belgians). The four musicians played on broken instruments … the keys on my upright piano remained lowered when depressed … it’s on this piano, with my three fellow musicians, dressed in the oddest way … completely tattered, and wooden clogs large enough for the blood to circulate despite the snow underfoot … that I played my quartet … the most diverse classes of society were mingled: farmers, factory workers, intellectuals, professional servicemen, doctors and priests. " (Source)

Considering the time period and conditions in which this piece was written, it would make sense to draw inspiration from the End of Days. As a piece of purely instrumental music being inspired by text, this is an example of program music, or "instrumental music based off a non-musical idea."

Watch the video presentation on 20th century chamber music and you'll learn more and will hear the first movement that incorporates bird calls by the clarinet.

(above): hoto of Olivier Messiaen by Rob C. Croes. Public Domain under Creative Commons.

(right): Richard Nunemaker and the Trio Oriens performs Quartet for the End of Time. Screenshot from YouTube.

George Crumb and Ancient Voices of Children.

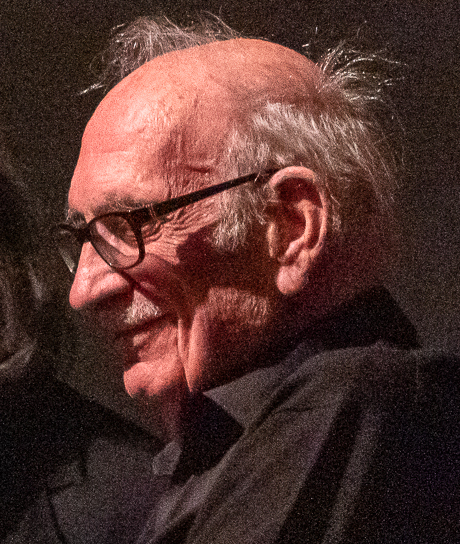

George Crumb's (1929-2022) music was even more dissonant and difficult to perform and listen to than those that came before him. He was an American composer who believed that the actual sheet music that performers played should be considered beautiful works of art. In the the video presentation on this unit, you'll actually see a page from his music that could easily be hung on the wall. It's also, as a result, incredibly difficult to learn!

George Crumb's (1929-2022) music was even more dissonant and difficult to perform and listen to than those that came before him. He was an American composer who believed that the actual sheet music that performers played should be considered beautiful works of art. In the the video presentation on this unit, you'll actually see a page from his music that could easily be hung on the wall. It's also, as a result, incredibly difficult to learn!

His music is considered "Avant-garde," which is a musical style that you'll read about next chapter. His music often incorporates theatrics -- performers move, act, shout, and sing while they perform. He often incorporated extended techniques in his music, which is a term that refers to the act of playing one's instrument in non-traditional ways. For an example of extended techniques, watch the first minute or so of this performance of E. Berrido's "Through the Path of Light". You'll see the pianist standing over the instrument, strumming the strings with the finger, then playing the keys while muting one of the strings to create a "plunk!" sound.

George Crumb often incorporated nonsensical words in his text---he would have singers shout or sing or combine shouting/talking and singing at the same time, yelling random syllables for effect.

One of his more celebrated works is titled Ancient Voices of Children, which contains several different movements. The instrumental ensemble is highly eclectic: female soprano, boy soprano, oboe, mandolin, harp, amplified piano, toy piano, and percussion! These instruments combined are highly unusual, but is par for the course in the 20th century.

Watch the video presentation on the movement titled "Dance of the Sacrd Life Cycle." When you're done, interested readers may watch the full 30-minute performance of this piece performed by the Bang on a Can fellows and faculty.

Photo of George Crumb by Peter Matthews. Creative Commons.