7.1: Early Keyboard Instruments through the Baroque Period

- Page ID

- 165649

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Keyboard Instruments.

After reading through page learning about early keyboard instruments, view the video presentation for this section.

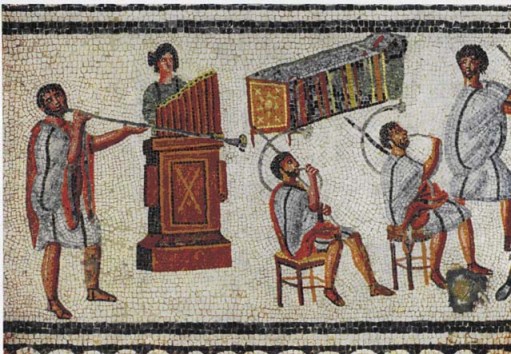

Part of the Zilten Mosaic from the 2nd century AD discovered in Libya, depicting the hydraulis, a water-powered organ. CC BY-SA 1.0

The Hydraulis.

The oldest-known hydraulis housed in the Archeological Museum of Dion, Greece. Picture by I. QuartierLatin1968, CC BY-SA 3.0.

When we think of keyboard instruments, we often think that they're much more modern than they really are. The piano, which is the most common acoustic keyboard instrument of the modern day was only invented around 1710. But organs -- a type of keyboard instrument --- have been around for over 2 millennia. The above picture depicts a person playing a hydraulis, which is a water-powered keyboard organ from the Ancient world. The hydraulis is the oldest-known keyboard instrument in recorded human history from around the 3rd century B.C., and is pre-cursor to the modern-day organ. The picture to the left is the oldest-discovered hydraulis from the 1st century B.C., and is housed in the Archeological Museum of Dion, Greece.

This instrument is very different from the keyboard instruments that we use today like the piano, harpsichord, clavichord, and virginal. These instruments all use strings in some capacity, as you'll read below. For the hydraulis, water pressure was used to create pressure for air to escape the pipes. Depending on the size and girth of the pipe, the sound would either be low or high (larger pipes created low pitches, while smaller pipes created higher pitches).

Watch this video of Justus Willberg performing a short piece on the hydraulis; you'll hear a very soft and almost flute-like sound escaping the various pipes that are pointing upward. This sound is very similar to some of the "flute" sounds heard on modern-day organs often heard in church music. You'll read more about the pipe organ below.

The Robertsbridge Codex.

While music notation is centuries old, modern Western musical notation dates back to around 650 A.D. If you look at early notation from this time period, you'll notice that there are some similarities to modern notation: there's a few horizontal lines (called the staff), and many dots placed on them. These dots don't look like modern notes (they're called neumes), but they function in a similar way. Benectine monk Guido d'Arezzo helped to establish the 5-line staff that we use today in the 10th and 11th centuries AD. The notation was still different than what we have today, but it was the beginning of what we consider modern notation.

The Robertsbridge Codex (pictured left) is an early manuscript that dates back to around 1360 (toward the end of the Medieval period) and contains the oldest music ever written solely for the keyboard. While we're not sure exactly what instrument it was written for, it's likely that it was some type of organ (we'll see the organ below).

Look at the manuscript to the left, and you'll see that it looks like modern music notation, but it also looks very different! Look closely, and you'll see the five lines that we still use today; notes all have stems, although the look like they're written backwards by today's standards. Scholars who study early music of the Medieval Period know how to translate the notation you see to the left into modern notation so that modern performers can play it. Take a listen to this modern recording of this performance of Daniel Mantey performing this piece on a clavichord, an early keyboard instrument.

Picture of the Robertsbridge Codex, taken from ClassicFM.

The Clavichord and the Virginal.

(left): Picture of a Virginal by Gérard Janot - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0.

(right): Picture of a Clavichord by Gérard Janot - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0.

Both the clavichord and virginal are similar keyboard instruments. While the clavichord was invented in the late Middle Ages (around 1300), the clavichord was invented around the Renaissance period (around 1500s). Both instruments are played by pressing a key, which in turn, moves a plectrum up, which plucks a string. The instruments therefore have a "twangy" effect, because you can actually hear the string being plucked (imagine plucking a guitar string with your finger nail, and that's the sound you get. Watch this video of Ernst Stolz performing a piece titled "Rowland" by John Dowland (1563-1626) an English Renaissance. Then, watch this video of Steven Devine demonstrating the sound of the Clavichord, creating a very different and more unique keyboard sound. As you listen to these pieces, you may think to yourself that these piece sound "old." Almost a "ye-olde" type of old. There is a reason for this: the music written in the Medieval Period (5th century-15th century) and the Renaissance 1400s-1600s) treated melody and harmony very differently than our modern music. And so not only do the timbres sound different, but the music itself is written using almost a different type of language than modern music!

You'll notice that the instruments are visually very stunning -- we saw the harpsichord in Chapter 5.2 on chamber music in the Baroque period (1600-1750). These instruments were treated not only as musical instruments, but also as beautiful works of visual art, hence the murals painted on the inside of the shells.

The Harpsichord.

The virginal from above is a member of the harpsichord family. The most common type of plucked keyboard instrument that we still see today is simply called the harpsichord (mostly because the other instruments like the virginal are no longer in widespread use). It was likely invented in the late Middle Ages (around 1300s) and was used prominently in the Baroque Era (1600-1750). It sounds similar to the virginal, but it produces a more powerful, richer, and fuller sound. The "twang" of the plucked strings are still present, which is common feature of all of these different keyboard instruments. Similar to the other instruments, the harpsichord is also highly ornamented with paintings and beautiful woodwork.

Unlike the clavichord from above, the harpsichord does not have "touch sensitivity." In other words, no matter how hard or soft you hit the key, the sound will always be the same loudness. To allow performers to get loud and soft sounds on their instrument, some harpsichords have two rows of keyboards on this instrument (similar to an organ). These keyboards are called manuals and it allows for performers to play loud and soft. Watch this video of Jean Rondeau performing J.P. Rameau's Les Sauvages (you'll need to mind the artsy camerawork; this is phenomenal performance, but the videography is a bit much!)

Pictured left: harpsichord, by Gérard Janot - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0.

The Pipe Organ.

Pipe organ at St. Germain cathedral in Paris, taken by Gérard Janot - Own work, Public Domain.

The modern pipe organ is many centuries old, and dates back to the 8th century. Rather than water pressure being used to create air pressure, a bellows was used instead. For smaller instruments, the performer would pump with their feet or knees to create a vacuum to collect air, and push it through the pipes as they played (you can see a short video of a performer doing there here). For larger instruments, performers would actually need someone to pump a bellows to do it for them!

Most organs have at least 2 manuals, though some of them have up to 7 different manuals! In addition to the manuals, organs also have a keyboard for the feet; performers thus perform on up to 7 different manuals with their hands, as well as a single manual with their feet.

The modern pipe organ is capable of playing literally hundreds of different sounds, each of which resemble real instruments. They can create reed sounds, string sounds, woodwind sounds, the typical "organ" sound, or combine them in dozens of ways. Depending on what the pipe is made of, its size and even shape, the sound will be completely different. This allows the performer to change sound, and combine a variety of different colors with one another. We often associate the organ with "church sound," at least from the Catholic perspective -- that's because up until the early 1960s, the Vatican wouldn't allow any other instrument in the Catholic church (with very little exception).

The beauty of the organ is that a single performer is able to perform multiple "instruments" at the same time -- a single performer can actually play a symphony by themselves!

Many composers of the Baroque Period (1600-1750) composed music solely for the organ. Some of the most famous organ works were composed by J.S. Bach (whom you read about in the earlier chapter 5.2). Arguably his most famous work for the organ is titled Toccata and Fugue in D Minor. Take a listen to organist Hans-Andre Stamm performing this famous work that's often associated with Halloween before moving on to the "Fugue." When you're done, watch this video presentation for the Organ, and you'll see just how complicated this instrument really is.

The Fugue.

The form of a 4-voice fugue.

Bach and his contemporaries wrote hundreds of fugues. Not all fugues are written for the organ, but Bach did write dozens of them for a solo organist.

Fugues are both a genre of music, and they also contain their form (called "fugue form"). All fugues are polyphonic in texture, and employ a compositional technique known as imitation. Think "row row row your boat," being sung as a round. This is imitation. All fugues contain at least 3 different layers called "voices" (even if it's an instrument and not being sung, it's still called a voice). Some fugues contain up to 7 voices -- that means that at any given time, the ear and brain can hear up to 7 distinct melodic layers happening at the same time! The fugue we're listening to in this unit is called the "Little Fugue in G Minor," which has 4 distinct voices.

Fugues have several sections: their first section is called the Exposition. Here, voice 1 plays a melody, that we call the subject. When it's done, voice 2 enters with the same melody through imitation, while voice 1 plays a counter-melody called the counter subject. When voice 2 finishes the subject, voice 3 then enters with the subject; when it's done, voice 4 then plays the subject while all the other voices continue to play their own thing. When all of the voices have finished playing the subject, the exposition is over and the music moves into the episode.

During the episode, the composer takes away the subject (we've heard it too much, and want a rest!) The composer will modulate, which means to change key to a new area, at which point the subject returns. When the subject returns, we call this a middle entry - in other words, the subject enters again, in the middle of the piece. After the middle entry, we move to another episode---then another middle entry, over and over until the composer decides to finish.

The diagram above demonstrates the entire form of Bach's "Little Fugue." The video presentation discusses this complex form in more detail, going through it section by section.

For those interested in downloading a PDF handout of this unit's PowerPoint slides, click here.