2.1.2: Grammar

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 211245

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

B.1 Definite and indefinite articles

In chapter one (B.5, page 44), we learned the forms of the definite articles in French. We remember that definite articles (le, la, les) must agree in gender and number with the noun they modify. The second type of articles we must learn in French are the indefinite articles. These correspond to the English a (an) (singular) and some (plural). Just like the definite article, the indefinite article has different forms for masculine, feminine, and plural.

| singulier | pluriel | |

| masculin | un [~œ] or [E] | des [de] |

| feminin | une [yn] | des [de] |

- The singular form, un/une, is the same as the number "one." There is no difference in French between "I have one brother" and "I have a brother." (J'ai un frère.)

- There are two possible pronunciations for un. There is a fourth nasal sound in French ([~œ]), traditionally used only for these letters "un" (or "um"). However, most places in France have lost this pronunciation and most French pronounce un as [ɛ̃], just like the letters "in," as in cinq. Speakers in some countries such as Belgium preserve the difference. We will use the traditional sound for the IPA transcription. Which pronunciation does your teacher use?

- Before a word beginning with a vowel, the "n" of un makes liaison with the next word: un homme is pronounced [~œ nɔm].

- In English, we often omit the article in the plural. For example, we might say "I have cats" instead of "I have some cats." In French, however, an article is almost always necessary.

The names definite and indefinite explain the basic differences between these two sets of articles. The definite articles refer to a specific object, "defined" in the speaker's mind as the only one, or the most important one, or the one whose context is clear. The indefinite articles refer to one thing among many; it is not specific, it is an "undefined" object. Consider these examples:

| Donnez-moi un stylo. | Give me a pen. (Any pen is fine.) |

| Donnez-moi le stylo. | Give me the pen. (You see a pen and ask for it.) |

| Voici un téléphone portable. | Here is a cell phone. (Someone hands another person a cell phone). |

| Voici le téléphone portable. | Here is the cell phone. (Someone finds their own cell phone in their house). |

|

In most cases, if you would say "the" something in English, you will use the definite article in French; if you would say "a" something in English, you will use the indefinite article in French.

B.1.1 Definite and indefinite articles

If a noun is masculine, it is always masculine. Therefore, a masculine noun always uses the masculine article and a feminine noun always uses a feminine article.

| definite | indefinite | |

| masculine singular | le / l' | un |

| feminine singular | la / l' | une |

| masculine or feminine plural | les | des |

Change each definite article below to the correct indefinite article (rewrite the noun for practice).

Exemple: la table une table

| 1. le sac ____________ | 5. le professeur ____________ |

| 2. la craie ____________ | 6. les étudiantes ____________ |

| 3. le stylo ____________ | 7. le tableau ____________ |

| 4. les chaises ____________ | 8. la porte ____________ |

B.1.2 Indefinite articles

Here, try to give the correct indefinite article by remembering the gender of the noun. After checking your answers, say these aloud for practice — the more you hear a word with the correct article, the more it will sound "right" to you and the easier it will be to remember. Remember that there is no difference between the masculine and feminine articles in the plural.

| 1. _______livre | 7. _______papiers |

| 2. _______fenêtre | 8. _______cahier |

| 3. _______affiche | 9. _______étudiante |

| 4. _______murs | 10. _______étudiant |

| 5. _______devoirs | 11. _______crayon |

| 6. _______carte téléphonique | 12. _______pupitre |

B.2 Prépositions de lieu - Prepositions of location

Prepositions are small words that indicate the relationship of one thing to another. Some of the most useful prepositions are the prépositions de lieu, or the prepositions of place. The prépositions de lieu are also some of the easiest prepositions to use properly, because their usage in French is very similar to their usage in English. Here are some of the most common prépositions de lieu. Some of them you have already seen in chapter one.

| sur | [syr] | on, upon, on top of |

| sous | [su] | under, beneath |

| dans | [dã] | in, inside |

| à côté de | [a ko te də] | next to |

| en face de | [ã fas də] | facing |

| devant | [də vã] | before, in front of |

| derrière | [dɛ rjɛr] | behind, in back of |

| à gauche de | [a go∫ də] | to the left of |

| à droite de | [a drwat də] | to the right of |

| entre | [ã trə] | between |

| près de | [prɛ də] | near, close to |

| loin de | [lwɛ̃ də] | far from |

| chez | [∫e] | at the house of |

| à | [a] | to, at, in, on |

It is true that sometimes, different prépositions de lieu are used in French than might seem logical to you; these are idiomatic expressions that you will learn as you go along in your French studies. For example, to say "on page 3," one says à la page 3; to say "in the picture," one says sur la photo. You should note that the two most common prepositions in French, à and de, have many meanings and will sometimes surprise you. À means "to" or "at," but also "in." De means "of" or "from" and is used in many compound prepositions, such as à gauche de ("to the left of") or à côté de ("next to," literally "at the side of"). However, in the vast majority of cases, the above prepositions will be used just as you would use them in English.

Note

After a preposition or a conjunction, we use a type of pronouns known as "stressed" pronouns. Since chez is a preposition, we must say chez moi (at my house), chez elle (at her house), etc. Here are the stressed pronouns for the six grammatical persons:

| moi me toi you lui him elle her nous us vous you eux them (masc.) elles them (fem.) |

We have included here the preposition chez. Chez means "at the house of" or "at the place of business of." It is a preposition, not a noun, and it does NOT mean "house." Chez can be followed with a noun, a name, or a stressed pronoun*. Chez le docteur, for example, would usually mean "at the doctor's office." Chez Georges means "at George's house" and chez toi means "at your house."

A final note: the preposition de combines with le to make du (de + le = du) and with les to make des (de + les = des). There is no contraction with l' or la (de l', de la). We will practice this contraction more in chapter 3, but you will use it here with the compound prepositions (e.g. en face de, à côté de, etc.).

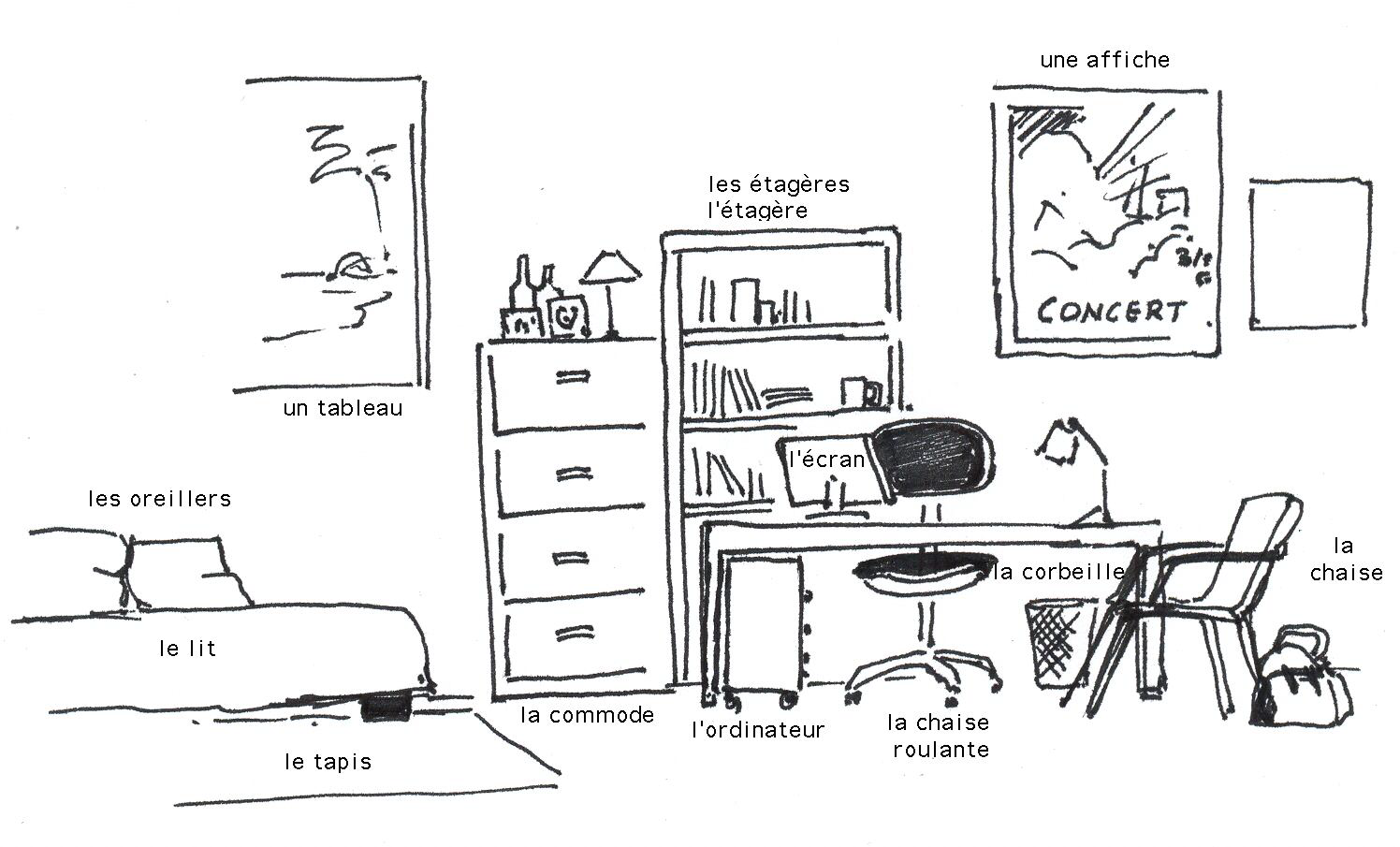

B.2.1 La chambre d’étudiant

Regardez le dessin et complétez les phrases. *Si c'est nécessaire, faites la contraction obligatoire de + le = du, de + les = des.

- La chaise est ____________le bureau.

- La commode est ____________l'étagère et le lit.

- Le tapis est ____________le lit.

- Les livres sont ____________les étagères.

- L'écran de l'ordinateur est ____________la chaise roulante.

- La colonne de l'ordinateur est ____________le bureau.

- L'affiche est ____________le bureau.

- La corbeille est ____________le bureau.

- Le lit est ____________*le bureau.

- Les oreillers sont ____________le lit.

- L'étagère est ____________la commode.

- Les photos sont ____________la commode.

- Le tableau est ____________l'affiche.

- Le lit est ____________la commode.

B.2.2 L’organisation de ma chambre

Choose the logical preposition. Vocabulary from exercise B.2.1.

- Mon téléphone portable est (dans / sur) mon sac à dos.

- Mes pull-overs sont (dans / entre) la commode.

- Mon tapis est (à gauche de / devant) ma porte.

- Mon lit est (loin de / sous) ma douche.

- Mon ordinateur est (derrière / sur) mon bureau.

- Mes livres sont (sur / devant) mes étagères.

- Ma porte est (en face de / sur) les fenêtres de ma chambre.

- Ma corbeille est (près de / entre) mon bureau.

- Mon armoire est (entre/ sous) mes étagères et mon commode.

- Mon table de nuit est (à gauche de / sous) mon lit.

B.3 Possession with Definite and Indefinite Articles

Possession with de

|

French has several ways to indicate possession, that is, to specify that an object belongs to a particular person. First, we can use the definite article and the preposition de. As we read earlier (B.1), the indefinite article (un, une, des) indicates an unspecified object, while the definite article (le, la, les) refers to a particular one. We might indicate a random book by saying, for instance:

| English | French |

| Here is a book. | Voici un livre. |

or we can designate a specific book by saying

| English | French |

| Here is Claire's book. | Voici le livre de Claire. |

| It's Claire's book. | C'est le livre de Claire. |

| These are Claire's books. | Ce sont les livres de Claire. |

Since the book is now a definite, specific one, the article changes from un livre ("a book") to le livre ("the book"). Furthermore, we know precisely which book it is: Claire's book, or, literally, "the book of Claire." Although we do not often use this structure to indicate possession in English, it usually makes sense to students.

| French | English |

| C'est la radio de Maryse. | It's Maryse's radio (= the radio of Maryse). |

| Je n'ai pas les clés de ma mère. | I don't have my mother's keys (=the keys of my mother). |

| J'aime les films de Francis Veber. | I like Veber's films (=the films of Veber). |

Possession with à

We can also use the expression être à to indicate that an object belongs to a person. This does not translate literally into English very well, so you will have to pay attention to the word order.

| French | English |

| La radio est à Maryse. | The radio is Maryse's (=literally, the radio is to Maryse). |

| Les clés sont à ma mère. | The keys are my mother's (=the keys are to my mother). |

| Le livre de maths est à lui et le livre de philo à moi. | The math book is his (=to him) and the philosophy book mine (=to me). |

Reminder

Stressed pronouns, used after prepositions:

moi me

toi you

lui him

elle her

nous us

vous you

eux them (masc.)

elles them (fem.)

As discussed in section B.2 re chez, after a preposition, we must use the stressed pronouns; since à is a preposition, in this structure you use the pronouns listed in the margin, rather than the subject pronouns, after the à.

B.3.1 Whose is this anyway?

A number of (American) friends have come over to your house to watch videos. They piled all their stuff on your bed, but a lot of it has fallen o and gotten mixed up. As you name each object, someone tells you that it belongs to the person whose name is indicated in parentheses. Follow the model and use the possessive structure with de. Pay attention to whether subject, and therefore the verb, is singular or plural.

Exemple: Voici un sac bleu. (Lydia) C'est le sac de Lydia.

Voici des livres. (Hamid) Ce sont les livres de Hamid.

- Voici un portable. (José)

- Voici un sac à dos brun. (Manuel)

- Voici une clé de voiture. (Aaron)

- Voici un cahier rouge. (Maria)

- Voici des CD. (Valérie)

- Voici des livres de français. (Paul)

- Voici un journal. (Leticia)

- Voici un stylo violet. (Ann)

- Voici des crayons. (Cuong)

- Voici une feuille de papier. (Lashonda)

B.3.2 Right again!

Your absent-minded friends have again left a number of items at your house. Luckily, your amazing powers of observation allow you to correctly identify the owners. Your friends conrm each of your statements. Use the possessive structure with être à and a stressed pronoun, following the model, to show what they say.

Exemple: Le porte-clé est à toi? Oui, le porte-clé est à moi.

| 1. Le téléphone est à Thomas? | 5. La clé est à Clement? |

| 2. Les classeurs sont à vous deux? | 6. Les CD sont à moi? |

| 3. Les baskets sont à Emma? | 7. Les devoirs sont à Kevin et à Romain? |

| 4. Les vidéos sont à toi? | 8. Les livres sont à Aurélie et à Mathilde? |

B.4 Possessive Adjectives

Possessive Adjectives

Finally, one can indicate possession by using a possessive adjective, the equivalent of "my," "her," "our," etc. You were introduced to some of these in chapter one (B.9, page 57), but there are more!

You will recall that possessive adjectives are used before the noun, much like an article, and must agree in gender and number with the noun they modify, like any article or adjective in French.

| French | English |

| Mon sac est bleu. | My purse is blue. |

| Ta mère s'appelle Renée. | Your mother is named Renée. |

| Leurs enfants sont grands. | Their children are big. |

Possessive adjectives are more complicated than the articles and adjectives we have seen before, however, because before worrying about agreement, we must first choose the adjective that designates the right person. Since there are six different grammatical persons, there are six sets of possessive adjectives (one for my, your, his, etc.). As we saw in chapter one, each has different forms for masculine/feminine and singular/plural. The following table places the forms of each possessive adjective next to the person they designate.

| Person possessing the object | possessive adjectives | Person possessing the object | possessive adjectives |

|---|---|---|---|

| je (I) | mon, ma, mes (my) | nous (we) | notre, nos (our) |

| tu (you) | ton, ta, tes (your) | vous (you) | votre, vos (your) |

| il, elle, on (he, she, it, one) | son, sa, ses (his, her, its, one's) | ils, elles (they) | leur, leurs (their) |

Let us first look at the possessive adjectives used when the possessor is a single person. In addition to mon, ma, mes and ton, ta, tes, which you know from chapter one, you must learn son, sa, ses for the third person singular.

My, your, his/her/its

| masculine singular object | feminine singular object | plural object | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st person singular (my) | mon [mɔ̃] mon père |

ma [ma] ma mère |

mes [me] mes parents |

| 2nd person singular (your) | ton [tɔ̃] ton père |

ta [ta] ta mère |

tes [te] tes parents |

| 3rd person singular (his/her/its) | son [sɔ̃] son père |

sa [sa] sa mère |

ses [se] ses parents |

|

Tips!!!

The choice of the possessive adjective depends on the person (whose it is).

The form of the possessive adjective depends on the gender and number of the possessed item itself.

Ma/ta/sa must change to mon/ton/son immediately before a vowel. Mes/tes/ses do not change.

- We can see from this table that we need to consider two things when deciding which possessive adjective to use. First, we must know who possesses the item. If I want to say his, I must use one of the forms son, sa, or ses.

- Next, we must know the gender and number of the possessed item. Like other adjectives, possessive adjectives agree with the noun they modify in gender and number. This point is very important, but can be hard for English speakers to understand. We say ma mère (my mother) using the feminine form of the possessive adjective because mère is feminine. It does not matter whether I am masculine or feminine, because the adjective (ma) agrees with the noun it describes (mère).

- Finally, there is one exception: mon/ton/son replace ma/ta/sa if the following word begins with a vowel. This does not change the gender of the noun — it is simply for pronunciation reasons, to avoid two vowels together. If we put another word between the possessive adjective and the noun, and that word begins with a consonant, the possessive adjective returns to the usual feminine singular form (ma/ta/sa). Compare:

| French | English |

| Mon ami | My (male) friend |

| Mon amie | My (female) friend (cannot use "ma" since "amie" begins with a vowel) |

| Mon meilleur ami | My best (male) friend |

| Ma meilleure amie | My best (female) friend (consonant after "ma", so the regular form is used) |

| Mes amies | My (female) friends (regular plural form) |

| Mes meilleures amies | My best (female) friends (regular plural form) |

B.4.1 C’est à moi!

Each of these items is yours; indicate your possession using the possessive adjectives mon, ma, mes. Remember that the number and gender of the object determines the form of the adjective.

Exemple: la photo C'est ma photo.

les devoirs Ce sont mes devoirs.

| 1. le portable | 6. l'examen |

| 2. le cahier | 7. les clés |

| 3. l'affiche | 8. le devoir |

| 4. les CD | 9. la voiture |

| 5. la chaise | 10. les exercices |

B.4.2 C’est à moi ou à toi?

You have been playing with your cousin Hélène all day. Now you are cleaning up Hélène's room and sorting out what belongs to whom. Hélène shows you an object and you tell her whose it is. Give an English translation for each of your French answers. Follow the model.

|

| les possessions d'Hélène | tes possessions |

| le sac rouge | le sac rose |

| le stylo bleu | le stylo noir |

| la poupée blonde | la poupée brune |

| la robe bleue | la robe violette |

| le jeu de Monopoly | les jeux vidéos |

| les cartes | les CD |

Exemple: A: Voici un stylo bleu. B: C'est ton stylo bleu. / It's your blue pen.

A: Voici des cartes. B: Ce sont mes cartes. / They are my cards.

| 1. Voici une robe violette. | 6. Voici des jeux vidéos. |

| 2. Voici une poupée blonde. | 7. Voici une robe bleue. |

| 3. Voici des CD. | 8. Voici un stylo noir. |

| 4. Voici un sac rose. | 9. Voici une poupée brune. |

| 5. Voici un jeu de Monopoly. | 10. Voici un sac rouge. |

Notes on his, her, and its

- The idea that the possessive adjective agrees with the noun it describes is particularly important for the third person forms. There is no difference in French between his, her, and its. "His mother," "her mother," and "its [e.g. the dog's] mother" are all "sa mère." This is because mère is feminine, so we must use the feminine form of the adjective. Remember: it is not the gender and number of the possessor that determines the form of the possessive adjective; it is the gender and number of the object possessed.

| French | English |

| le sac | the bag (masculine) |

| son sac | his bag OR her bag |

| la chambre | the room (feminine) |

| sa chambre | his room OR her room |

- If you need to clarify "his" or "hers," you may add "à + stressed pronoun" after the noun.

| French | English |

| C'est son sac à elle. | It's her purse. |

| C'est son sac à lui. | It's his bag. |

B.4.3 C’est à lui?

Exemple: C'est le stylo de Marie? Oui, c'est son stylo. / Yes, it's her pen.

Ce sont les CD d'Alain? Oui, ce sont ses CD. / Yes, they are his CDs.

Note that the first example uses the masculine singular possessive adjective son because le stylo is masculine singular; the second uses the plural possessive adjective ses because les CD is plural.

- C'est l'ordinateur de Paul?

- Ce sont les photos d'Anne-Marie?

- Ce sont les devoirs de José?

- C'est la clé de Marc?

- C'est le livre d'Alice?

- Ce sont les aches de Clarisse?

- C'est la chambre de ton frère?

- Ce sont les clés de ton père?

B.4.4 C’est à qui?

Now, using all three groups of possessive adjectives you have practiced so far (mon, ma, mes; ton, ta, tes; and son, sa, ses), rewrite each sentence below by using a possessive adjective. You are changing from one possessive structure (être à + person) to another (possessive adjective). Remember: the form of the adjective depends on the gender and number of the object. Carefully observe and then follow the model.

Exemple: Le livre est à moi. C'est mon livre.

Les aches sont à Marie. Ce sont ses aches.

| 1. Le lecteur mp3 est à moi. | 5. Les CD sont à Marc. |

| 2. La voiture est à Eliane. | 6. La clé est à moi. |

| 3. L'ordinateur est à Crystal. | 7. La maison est à Paul. |

| 4. Le livre est à toi. | 8. Les devoirs sont à toi. |

B.4.5 C’est à toi ou à lui?

You are helping your friend Amélie clean house after her breakup with her boyfriend. You are not always sure which things are hers and which are her boyfriend's. You ask her about different objects, and she responds. Carefully observe and then follow the model.

| les possessions d'Amélie | les possessions de Julien |

| le téléphone portable | les CD des Nubians |

| le cahier noir | les livres de maths |

| les fiches de vocabulaire | la clé |

| la photo | la carte téléphonique |

| l'ordinateur portable | le mp3 |

| l'affiche | la plante |

Exemple: Le cahier noir? C'est mon cahier noir.

les CD des Nubians? Ce sont ses CD.

| 1. les livres de maths? | 6. le téléphone portable? |

| 2. la carte téléphonique? | 7. l'affiche? |

| 3. les fiches de vocabulaire? | 8. la clé? |

| 4. le mp3? | 9. l'ordinateur? |

| 5. la plante? | 10. la photo |

Our, your, their

When items are owned by more than one person, the forms of the possessive adjectives are somewhat easier. Here, there are only two forms: one if the item possessed is singular, another if it is plural.

| singular object | plural object | |

|---|---|---|

| first person plural (our) | notre [nɔtr] notre voiture |

nos [no] nos voitures |

| second person plural (your) | votre [vɔtr] votre voiture |

vos [vo] vos voitures |

| third person plural (their) | leur [lœr] leur voiture |

leurs [lœr] leurs voitures |

- Remember that the final -s is usually silent in French. Whereas English speakers listen for that final -s to tell whether a noun is plural, French speakers instead listen to the form of the article. The possessive adjectives, like the indefinite and definite articles, signal the difference between singular and plural. Notre voiture ([nɔ trə vwa tyr]) means our car (we have one car); nos voitures ([no vwa tyr]) means our cars (we have more than one car).

- However, in the third person plural, leur voiture (their car) sounds exactly like leurs voitures (their cars) [lœr vwa tyr]. With leur, the only way you can hear the difference between a singular and plural possessed object is if the word following leur(s) begins with a vowel, in which case liaison (=pronouncing the final -s) occurs. For example, leur ami ([lœ za mi]) sounds different from leurs amis ([lœr za mi]). In other cases, French speakers must figure out from context whether the object is singular or plural, or ask for clarication.

B.4.6 C’est à vous?

Note to Spanish Speakers

While Spanish speakers usually have an easier time with gender and number agreement than English speakers, the possessive adjectives tend to be equally difficult for the two groups, because Spanish possessive adjectives do not differentiate gender but only number (e.g. mi/mis). In particular, since su/sus in Spanish can mean his, her, your, and their, Spanish speakers need to pay special attention to the difference between all these forms in French.

You and your friends are cleaning up after a long study session. Answer the questions using a possessive adjective. If vous is used, assume it is informal plural, and answer with the nous form. Carefully observe and then follow the model.

Exemple : Le livre est à vous? Oui , c'est notre livre.

Ces fiches sont à Benoît et à Audrey? Oui, ce sont leurs fiches.

| 1. Les classeurs sont à vous? | 5. C'est notre cahier? |

| 2. L'ordinateur portable est à Alexandra et à Francois? | 6. Les magazines sont à tes soeurs? |

| 3. C'est votre clé? | 7. Les notes sont à vous? |

| 4. Ces livres sont à nous? | 8. Les stylos rouges sont à tes parents? |

B.4.7 Faire les bagages

The Martin, Legrand, and Kouassi families have been camping together. The Legrands had to return home unexpectedly, and the Martins and Kouassis find some of the Legrands' items mixed in with their own. Solange Martin shows two items to Yasmine Kouassi, who then tells her to whom each item belongs. Note: Pay attention to meaning. Since Yasmine Kouassi is speaking to Solange Martin, she will refer to items belonging to the Kouassis as notre/nos, items belonging to the Martins as votre/vos, and items belonging to the Legrands as leur/leurs. Carefully observe and follow the model.

| Les Martin | Les Legrand | Les Kouassi |

| le shampooing | la crème solaire | le sac de couchage |

| les livres | la tente | les coquillages |

| le maillot de bain | les hamsters | la torche |

| les souvenirs de vacances | les feuilles rouges | les lunettes de soleil |

Exemple: Solange montre: Yasmine dit:

Les feuilles et la torche Ce sont leurs feuilles et notre torche.

- Les souvenirs de vacances et le sac de couchage

- Le maillot de bain et les lunettes de soleil

- Les coquillages et la crème solaire

- Les hamsters et le shampooing

- La tente et les livres

B.5 The verb avoir

Mini-Vocabulaire: crème solaire sunblock |

Logically, if we are discussing possessions, we need to learn a new verb, the verb avoir (to have). As we learned with the verb être, a French verb must be conjugated, that is, placed in the proper form to agree with its subject. Although memorizing irregular verbs is difficult at first, it will soon become easier, for you will begin to see patterns, such as the fact that all tu forms end in -s. Learning the correct spelling of each verb form from the start is therefore crucial — it will make you more aware of conjugation patterns, and will also give you a solid base should you wish to go on and learn more French. It is always easier to learn something correctly the first time than to relearn it later!

Like être, the verb avoir (to have) is an irregular verb. That means that its forms do not follow a regular pattern and must be memorized individually (Unfortunately, the most common verbs are also the most irregular, because they are used so often that speakers of a language are less apt to change them over time to follow patterns as they do with less commonly used words.)

Here are the forms of avoir and their equivalents in English.

| avoir [a vwar] | |

|---|---|

| j'ai [ʒe] | nous avons [nu za vɔ̃] |

| tu as [ty a] | vous avez [vu za ve] |

|

il a [i la] elle a [ɛ la] on a [ɔ̃ na] |

ils ont [il zɔ̃] elles ont[ɛl zɔ̃] |

| to have | |

|---|---|

| I have | we have |

| you have | you have |

|

he/it has she/it has one has |

they have |

- When the verb form begins with a vowel, je changes to j'. This elision always occurs when je precedes a vowel or silent h, just as it does with the definite articles le and la. Remember that when elision is made between two words, they are pronounced as one word, with no hesitation or pause between them. Note the liaison in the plural forms. In each case, the "s" of the pronoun is linked to the following vowel sound and pronounced like a [z]. When the letter "s" makes liaison, it is always pronounced as a [z]. This is an important point, since the only pronunciation difference between ils sont ("they are") and ils ont ("they have") is the s/z sound: ils sont = [il sɔ̃], ils ont = [il zɔ̃].

- The nous and vous forms of avoir use the regular endings for the nous and vous forms of verbs. Nous forms of verbs almost always end in the letters -ons (the only exception is être), and vous forms almost always end in the letters -ez (there are only three exceptions in the entire language).

- Note: this is the last time we will give you the English equivalents for each form of the verb. If you are still confused about what the different French subjects and verb forms mean, please consult your professor.

B.5.1 Practice conjugation, avoir

Reminder

Elision means replacing the final vowel in certain short words with an apostrophe if the next word begins with a vowel. Liaison means pronouncing the last consonant of a word to connect it to the next word. Elision involves a spelling change; liaison involves only a pronunciation change.

Let's practice the conjugation by writing it out a few times. If your teacher has already demonstrated the correct pronunciation of the forms to you, please read the forms out loud to yourself as you write them. Refer to the IPA to refresh your memory of your teacher's model pronunciation. Remember to elide je before a vowel.

|

avoir je ___________________ |

avoir je ___________________ |

avoir je ___________________ |

B.5.2 Verb endings, avoir

The last letters of the tu, nous, vous, and ils forms of the verb avoir are typical, even though the verb as a whole is irregular. Fill in the missing letters below to become more familiar with the typical endings for these forms.

| j'ai | nous av _______ | j'ai | nous av _______ |

| tu a _______ | vous av _______ | tu a _______ | vous av _______ |

| il/elle a | ils/elles o _______ | il/elle a | ils/elles o _______ |

B.5.3 Conjugating avoir

|

Write the proper form of the verb avoir in each blank. Remember to elide je before a vowel.

Tous les étudiants ont des sacs à dos. Qu'est-ce qu'ils ont dans leurs sacs?

- Je _____________________deux livres et un cahier.

- Marie _____________________un sandwich.

- Nous _____________________des photos de notre famille.

- Philippe _____________________un classeur.

- Christine et Suzanne _____________________des stylos.

- Hélène _____________________son téléphone portable.

- Vous _____________________des clés?

- Je _____________________une orange.

- Georges et Marie _____________________leurs portefeuilles.

- Le professeur _____________________les devoirs des étudiants.

- Tu _____________________des fiches de vocabulaire?

- Paul et moi _____________________nos devoirs.

B.5.4 Etre ou avoir?

At the beginning of your French studies, it is important to think about the meaning of each verb. Consider the meaning of each sentence and complete it with the appropriate form of the verb être (to be) or avoir (to have). Translate each sentence.

- Le professeur _____________________trois cent livres.

- Je _____________________étudiant.

- Marie et Marc _____________________des devoirs.

- Un tigre _____________________un animal dangereux.

- Nous _____________________américains.

- Tu _____________________un ordinateur portable.

- Je _____________________des amis en France.

- Mes parents _____________________petits.

B.6 Il y a

An important form of the verb avoir is the phrase il y a. Il y a, which derives from the form il a ("it has"), means "there is" or "there are." This expression never changes form, whether the item that follows it is singular (il y a meaning "there is") or plural (il y a meaning "there are").

| French | English |

| Il y a un seul professeur dans chaque classe. | There is only one teacher in each class. |

| A cette université, il y a beaucoup d'étudiants. | There are many students at this university. |

"Il y a" is often seen in questions:

| French | English |

| Est-ce qu'il y a un médecin dans la salle? | Is there a doctor in the house? |

| Combien d'étudiants est-ce qu'il y a dans la classe? | How many students are in the class? |

| Qu'est-ce qu'il y a dans votre sac? | What is in your purse/ bag? |

B.6.1 Questions et réponses - il y a

Répondez aux questions. Utilisez il y a dans votre réponse.

- Est-ce qu'il y a des pupitres dans la salle de classe?

- Est-ce qu'il y a des étudiants intelligents à cette université?

- Est-ce qu'il y a une cafeteria à l'université?

- Combien de fenêtres est-ce qu'il y a dans la salle de classe?

- Combien de personnes est-ce qu'il y a dans votre famille?

- Combien de personnes est-ce qu'il y a à Los Angeles?

- Qu'est-ce qu'il y a dans votre sac?

- Qu'est-ce qu'il y a dans la salle de classe?

- Qu'est-ce qu'il y a sur votre bureau?

Il y a and Voilà

|

You have already seen the expression voici which means "here is." Its sister expression, voilà, means "there is," but with a different meaning than il y a. Voilà literally comes from the words for "look there!" and serves to point out someone or something. Often, you will see le voilà, la voilà, les voilà which mean "there he/it is!" "there she/it is!" "there they are!" respectively.

Il y a, on the other hand, means that something exists in a given place. Compare:

| English | French |

| There is the teacher. | Voilà le professeur. |

| There is the museum. | Voilà le musée. |

| There is a desk in the classroom. | Il y a un bureau dans la salle de classe. |

| There are some books in my bag. | Il y a des livres dans mon sac. |

These kinds of differences can be very tricky to a language learner. An English speaker might think that it does not matter which of these phrases she uses, because "they mean the same thing." But in fact, to a French speaker, they mean very different things, and it is only because the same words are used in English for two different meanings that they seem "the same" to an English speaker! Always remember, as you study French, that French is not a "copy" of English.

B.6.2 There it is!

Complete the sentences with il y a or voici or voilà as appropriate according to the context.

- Est-ce que le professeur est ici? La __________________!

- __________________des devoirs sur le bureau du professeur.

- Bonjour, les étudiants! __________________les devoirs.

- Dans mon sac, __________________des livres et des cahiers.

- Ou sont les toilettes? Les __________________.

- Est-ce qu' __________________un bon restaurant mexicain a Pasadena?

- Je suis en retard! Ah, __________________le bus!

B.6.3 What’s missing?

Mini-Vocabulaire: un garçon boy |

In the following exercise, each blank marks either a subject pronoun or a verb that is missing. Consider the sentence structure in order to fill in the missing word. If the subject is missing, figure out what it must be from the verb form; if the verb is missing, use the subject to come up with the proper form of the verb avoir. Also translate the passage.

| Dans notre classe de français, il y ________________30 étudiants. ________________y a 12 garçons et 18 filles. Nous ________________ beaucoup de devoirs. Moi, ________________ai 3 autres cours, et je n' ________________pas toujours le temps pour mes devoirs. Le professeur ________________beaucoup de patience. Deux de mes amis sont aussi dans cette classe. Ils ________________de bonnes notes. Et toi, quels cours as- ________________ce trimestre? |

B.7 Simple Negation

To make a sentence negative in French, we put ne . . . pas around the verb. The ne is placed before the verb, and the pas after it.

| French | English |

| Je suis intelligente. | I am intelligent. |

| Je ne suis pas stupide. | I am not stupid. |

| Abdul est grand. | Abdul is tall. |

| Abdul n'est pas petit. | Abdul is not short. |

- Note that ne elides if the following word begins with a vowel. As in all cases of elision, this change is obligatory.

- Note: the negative of il y a is il n'y a pas.

B.7.1 Non!

Contradict each of the following sentences. Use a negative construction. Replace the subjects with subject pronouns (e.g. Marc becomes il).

Exemple: Je suis stupide. Tu n'es pas stupide!

- Dominique est grand.

- Pascale est petite.

- Jérémy est intelligent.

- J'ai trois voitures.

- Nous avons cinq chiens.

- Marthe est étudiante.

- David et Loïc sont travailleurs.

- Tu es riche.

B.7.2 In other words

Write a negative sentence that conveys a similar meaning to the affirmative sentence. To do this, you will have to make the verb negative, and change the adjective or noun after the verb.

Exemple: Je suis grand. Je ne suis pas petit.

- Je suis intelligent.

- Barack Obama est américain.

- Nous sommes étudiants.

- Jean-Luc est paresseux.

- Mireille va bien.

- Le professeur a les devoirs.

- Tu es active.

- Mes amis ont quatre cours.

Negative before indefinite articles

List of words that elide

You have now encountered several of the words that undergo elision (the loss of a letter before a following vowel). There are eleven in all. In case you are curious, here is the complete list (you do not have to memorize it yet).

Definite articles:

le and la

Pronouns:

ce, je, me, te, and se

Preposition:

de

Conjunction:

que

Negative:

ne.

Note that these are all one syllable words ending in -e, except for la.

Finally, the word si (if) elides, but only in front of the pronouns il/ils, not in front of any other words.

When a negative occurs before an indefinite article, the indefinite article (un, une, des) must be changed to de. De elides to d' before a vowel. Compare:

| J'ai un sac. | Je n'ai pas de sac. |

| Ils ont des billets pour le match. | Ils n'ont pas de billets pour le match. |

| Il y a une pendule au mur. | Il n'y a pas de pendule au mur. |

| Elle a des amis en France. | Elle n'a pas d'amis en France. |

An important exception to this is if the verb is être. After être in the negative, the indefinite article remains unchanged.

| Je suis un étudiant paresseux. | Je ne suis pas un étudiant paresseux. |

| Qu'est-ce que c'est? C'est un chien? | Ce n'est pas un chien; c'est un chat. |

The definite article (le, la, les) does not change after a negative.

| Georges a le livre. | Georges n'a pas le livre. |

| Christine déteste les sandwichs. | Christine ne déteste pas les sandwichs. |

To summarize: the definite article does not change after a negative. The indefinite article changes to de after a negative, unless the negative verb is être.

B.7.3 Qu’est-ce qu’il y a sur la photo?

Read the conversation and underline the negatives. Then circle the places where de or d' replaces un, une, or des after a negative — look for these immediately after the negative, in places where you would expect to see an indefinite article before a noun. (Do not replace other uses of the preposition de, e.g. the possessive.) If you write your homework on a separate sheet, write out the entire passage.

Eric et Richard regardent une photo dans le journal.

Eric: Qu'est-ce que c'est?

Richard: C'est une photo de Claude avec un chien.

Eric: Ce n'est pas Claude, c'est Pascal, l'étudiant qui a une mère américaine et un père français.

Richard: Pascal a un père américain, mais sa mère n'est pas américaine.

Eric: C'est le chien de Pascal dans la photo?

Richard: Non, Pascal n'a pas de chien. Ils n'ont pas d'animaux du tout.

Eric: C'est qui l'étudiant avec Pascal?

Richard: Je ne sais pas. C'est un ami de Pascal.

Eric: Ce n'est pas un ami de Pascal. Il n'a pas d'amis! Il est trop egoste.

B.7.4 Ah non, ce n’est pas vrai!

Change the affirmative sentences to negative sentences. Change the form of the article if necessary.

- Il y a des chaises dans la salle de classe.

- Madame Leblanc est le professeur.

- J'ai un ordinateur.

- L'étudiant regarde la télé.

- Mes parents ont des amis en France.

- Les étudiants ont des stylos dans leur sac.

- Marie a une fenêtre dans sa chambre.

- Liberté est un livre d'espagnol.

B.8 Age

Idiomatic Expressions with avoir

French grammar is similar to English grammar in many ways. In many cases, if we understand each word in a sentence, we can translate them one by one into English and understand it perfectly. Most of the sentences we have formed thus far fall into this category. However, every language also has a great number of idiomatic expressions — these are phrases that are always said in a certain way in one language, but do not correspond word-for-word to the other language. For example, you have already encountered the phrases Je m'appelle and Comment vas-tu? Word-for-word, these sentences translate into English as "I myself call" and "How go-you?", but they are in fact equivalent to the English "My name is" and "How are you?". If you were to take the French words for "How" "are" and "you" and put them in a sentence one at a time, you would get Comment es-tu?, which means not "How are you?" but "What are you like?"

Therefore, while a great deal of learning a language consists in learning vocabulary, you will not always be able to learn this vocabulary word-by-word. In the case of idiomatic expressions, you will have to learn the meaning of an entire expression in one piece.

The verb avoir is used in many idiomatic expressions in French.

Avoir + âge

A very important idiomatic use of avoir is to express age. Whereas in English we use the verb to be for this purpose, French uses the verb avoir.

Questions used to ask someone's age are, for example,

| French | English |

| Quel âge avez-vous? | How old are you? |

| Quel âge as-tu? | How old are you? |

| Quel âge a-t-il? | How old is he? |

| Quel âge a ta mère? | How old is your mother? |

The answer also uses avoir, for example,

| French | English |

| J'ai dix-huit ans. | I am eighteen. |

| Il a dix mois. | He is ten months old. |

| Ma mère a cinquante ans. | My mother is fifty. |

- Notice that you must use the word ans (years) (or in rare cases, mois, months), because otherwise you are simply saying "I have 18," and you must say what you have 18 of!

B.8.1 Qui a quel âge?

Read the following sentences, then fill in the blank with the most logical name.

Monsieur Pernel est très âge.

Jacques Witta est encore à l'ecole élémentaire.

Caroline est adolescente.

Naima est grand-mère.

Hans est étudiant a l'université.

Jean-Luc a trois enfants (Julia 13 ans, Amélie 11 ans, Christophe 7 ans).

| 1. ___________a 19 ans. | 4. ___________a 14 ans. |

| 2. ___________a 98 ans. | 5. ___________a 65 ans. |

| 3. ___________a 41 ans. | 6. ___________a 9 ans. |

B.8.2 Quel âge ont-ils?

Read when the following people were born, and then tell how old they are on their birthday this year.

- Manuela est née le 8 août 2000. Elle _______________________

- Stéphane est né le 18 janvier 1997. Il _______________________

- Raja est né le 7 juillet 1981. Il _______________________

- Mme Fuji est née le 23 mars 1976. Elle _______________________

- Mes oncles sont nés le 3 avril 1962. Ils _______________________

- Je suis née le 14 juillet 1965. Tu _______________________

- Vous êtes nés en 1994. Nous _______________________

- Maryse est née le 11 décembre 2007. Elle _______________________

- Nous sommes nés en 1940. Vous _______________________

B.9 Idiomatic Expressions with avoir

In addition to avoir + age, there are a number of other idiomatic expressions using avoir. In each of them, you conjugate the verb avoir to match the subject.

Usually, students will quickly learn to recognize expressions such as j'ai froid, j'ai de la chance, j'ai sommeil, but it is much harder for beginning speakers to use them correctly. The more you hear and use them, however, the more natural they will come to seem to you. Language learners are often told not to translate to or from their native language, but a certain amount of translation is inevitable in the early stages of learning a new language. The trick is to realize (through practice) when you cannot translate literally and must use an entire phrase as one unit, without stopping to consider what each word means. Try to remember to think of the entire avoir + noun phrase as its English equivalent, and not get stuck on the fact that a different verb (such as to be) is used in English.

Physical Conditions

Avoir is used in many expressions that describe physical conditions. Whereas in English, we say "I am cold, I am hungry, I am sleepy," in French these expressions use avoir instead of être, and the verb is followed by a noun, not an adjective. What you say in French literally (word-for-word) translates into English as, "I have cold," "I have hunger," "I have sleepiness."

Some idiomatic expressions using avoir that describe physical conditions include:

| avoir faim | [a vwar fɛ̃] | to be hungry |

| avoir soif | [a vwar swaf] | to be thirsty |

| avoir sommeil | [a vwar sɔ mɛj] | to be sleepy |

| avoir froid | [a vwar frwa] | to be cold |

| avoir chaud | [a vwar ∫o] | to be hot |

To use these expressions, or any idiomatic expression using avoir, you must conjugate the verb to match the subject. Note that since the words after avoir are nouns and not adjectives, they do not change in any way.

| French | English |

| Il a faim. | He is hungry. |

| Elles ont soif. | They are thirsty. |

| J'ai toujours froid. | I am always cold. |

B.9.1 Les conditions physiques

Using avoir faim, avoir soif, avoir sommeil, avoir froid, or avoir chaud, complete the sentence logically, conjugating the verb.

- Je participe au marathon de Los Angeles — je ______________________.

- Nous sommes dans le désert du Sahara. Nous ______________________.

- Karl est au pôle nord en décembre. Il ______________________.

- Il n'y a pas de steak dans le frigo. Mes frères ______________________.

- Il est minuit. Est-ce que tu ______________________?

- Tu manges quatre sandwichs parce que tu ______________________.

- Ma mère a une eau minérale parce qu'elle ______________________.

- La fenêtre est ouverte en décembre. Vous ______________________.

- J'ai un devoir sur un livre d'anglais qui n'est pas intéressant! Je ______________________.

- Les cousines sont à la plage en juillet. Elles ______________________.

|

As you may have noticed in activity A.2.9, avoir is also used with certain expressions describing parts of the body:

| French | English |

| Elle a les cheveux longs. | She has long hair. |

| J'ai les yeux bruns. | I have brown eyes. |

| Il a les cheveux blonds. | He has blond hair. |

It is very common for French speakers to use these expressions.

Avoir raison et avoir tort

"To be right" and "to be wrong" are avoir raison and avoir tort in French. These expressions have both literal and ethical or moral connotations in French, just as they do in English. Compare:

| French | English |

| 2+2=4? Tu as raison! | 2+2=4? You're right! |

| Elle a tort. Bill Clinton n'est pas le président. | She's wrong. Bill Clinton is not the president. |

| Tu as raison de parler français en classe. | You're right (you do well) to speak French in class. |

| Il a tort de ne pas écrire à sa grand-mère. | He is wrong (he does badly) not to write to his grandmother. |

B.9.2 Raison ou tort?

|

The verb used at the beginning of each sentence is the verb dire, "to say" or "to tell." This verb is irregular. Its forms are:

|

Respond to each person's statement by saying whether they are right or wrong. Conjugate the verb avoir correctly to correspond to the subject (the person you are talking to or about). If the person's assertion is wrong, give the correct fact.

Exemple: Je dis: Nice est la capitale de la France. Tu as tort. Paris est la capitale de la France.

- Georges dit: 17-14=3.

- Mes parents disent: Le français est une belle langue.

- Je dis: Jennifer Lopez est blonde.

- Nous disons: "Pièce" veut dire "kitchen."

- Marie dit: L'Algérie est en Europe.

- Je dis: 10% de la population en France est étrangère.

- Les professeurs disent: Il est important d'étudier avant l'examen.

- Nous disons: Nous allons étudier avant l'examen!

Needs and Wants

|

Note

Literally, these expressions translate as, "I have need of" and "I have want of." That may help you to remember why the de is necessary.

Two other useful idiomatic expressions using avoir are a little more complex. We can use these before either an innitive verb or a noun.

| avoir besoin de | [a vwar bə zwɛ̃ də] | to need |

| avoir envie de | [a vwar ã vi də] | to want |

To use these, we must conjugate the verb avoir and use the preposition de to link to the thing needed or wanted.

| French | English |

| Je prepare un examen. J'ai besoin d'un stylo. | I'm studying for a test. I need a pen. |

| J'ai sommeil. J'ai besoin de dormir. | I'm tired. I need to sleep. |

| Ça va mal. J'ai besoin d'aspirine. | I don't feel well. I need aspirin. |

| J'ai chaud. J'ai envie d'un coca froid. | I'm hot. I want a cold soda. |

| J'ai froid. J'ai envie d'un café chaud. | I'm cold. I want a cup of hot coffee. |

| J'ai faim. J'ai envie de manger. | I'm hungry. I want to eat. |

B.9.3 Nos besoins

Match the situation on the left with the item needed on the right.

| 1. Nous avons soif. | a. J'ai besoin d'un pull-over. |

| 2. Il y a un lm super au cinéma. | b. Nous avons besoin de crème solaire. |

| 3. J'ai froid. | c. J'ai besoin de 10 dollars. |

| 4. Tes cheveux sont trop longs. | d. J'ai besoin d'une douche. |

| 5. Il y a beaucoup de devoirs. | e. Tu as besoin d'une nouvelle coiffure. |

| 6. Nous sommes à la plage. | f. J'ai besoin d'une télé. |

| 7. Tu es dans un accident. | g. Nous avons besoin de notre clé. |

| 8. J'ai très chaud. | h. Nous avons besoin d'eau minérale. |

| 9. J'adore "True Blood." | i. Vous avez besoin de vos livres. |

| 10. Nous sommes à notre porte. | j. Tu as besoin de ton téléphone portable. |

B.9.4 “You Can’t Always Get What You Want”

|

For each situation, name one item that the people want, and one item that they need. Write one sentence using "avoir envie de" and sentence using "avoir besoin de." The idea is that one might want something better, but one can settle for the minimum - - one might want a Mercedes, but one needs a car.

Exemple:

Le professeur a besoin de corriger les devoirs.

Elle a envie d'une assistante. Elle a besoin d'un stylo rouge.

Suggestions:

| un bureau | une bicyclette |

| une voiture | quatre chambres |

| un bus | un job à Target |

| une table | une chaise en bois |

| deux chambres | un fauteuil |

| un lave-vaisselle | un ordinateur portable |

| une tante riche | un smartphone |

- L'appartement de Marie et de Julie est à 10 kilomètres de l'université.

- Il y a 4 enfants dans la famille de Martin.

- Antoine est fatigué et il veut s'asseoir.

- Nous avons besoin de payer 1000 dollars à l'université.

- J'ai envie de preparer mes devoirs à l'ordinateur.

- Il y a dix personnes à dîner chez nous.

- Paul a envie de preparer ses devoirs dans sa chambre.

Other expressions using avoir

There are many other idiomatic expressions with avoir. The last ones we will learn in this chapter are

| avoir de la chance | [a vwar də la ∫ãs] | to be lucky |

| avoir l'air | [a vwar lɛr] | to seem, to look (+ adjective) |

| avoir l'air de | [a vwar lɛr də] | to seem to be (+ verb) |

| French | English |

| Le professeur est malade et il n'y a pas d'examen? Nous avons de la chance! | The professor is sick and there is no exam? We are lucky! |

| Le pauvre homme n'a pas de chance. | The poor man has no luck. |

| Cette fille a l'air serieux. | That girl seems serious and reliable. |

| Tu as l'air de rêver. | You seem to be dreaming. |

Here are all the avoir expressions you have learned in this chapter.

| French (English) | French (English) |

| avoir X ans (to be X years old) | avoir les cheveux . . . (to have . . . hair) |

| avoir besoin de (to need) | avoir les yeux . . . (to have . . . eyes) |

| avoir chaud (to be hot) | avoir quel âge (to be how old) |

| avoir de la chance (to be lucky) | avoir raison (to be right) |

| avoir envie de (to want) | avoir soif (to be thirsty) |

| avoir faim (to be hungry) | avoir sommeil (to be sleepy) |

| avoir froid (to be cold) | avoir tort (to be wrong) |

| avoir l'air (de) (to seem) |

B.9.5 Qu’est-ce qu’ils ont?

Mini-Vocabulaire: malade sick |

Respond to each sentence by using an expression with avoir. Use your imagination to try to t one of the expressions from the list above to each situation.

Exemple: Florian est malade. Sa température est de 40 degrès. Il a chaud.

- Francois désire aller au cinéma. Il n'a pas d'argent. Il . . .

- —J'adore le café et j'ai soif. —Tu . . .

- L'homme dans le métro a un grand livre de physique. Il . . .

- Il est minuit. Je . . . .

- C'est décembre a Moscou. Les Moscovites . . .

- Mes parents adorent les enfants, et ils ont six enfants! Ils . . .

- C'est l'anniversaire de Liliane. Elle est née en 1907. Elle . . .

- La jeune fille a de beaux yeux. Elle . . .

- La température est de 38 degrès! Nous avons . . .

- Ah, c'est ton anniversaire? Tu . . .

- Les étudiantes pense que le Quebec est un pays. Elles . . .

- La famille pauvre n'a rien dans le frigo. Ils . . .

- Vous pensez que Paris est la capitale de la France? Vous . . .

- Mon professeur de français est vietnamien. Il . . . [cheveux]

- J'ai envie d'une grande bouteille d'eau! J' . . .

In French, as in most languages, speakers often abbreviate words or phrases. In English, we say "cell phone" instead of "cellular telephone"; in French, one can say "le portable" instead of "le téléphone portable."

In French, as in most languages, speakers often abbreviate words or phrases. In English, we say "cell phone" instead of "cellular telephone"; in French, one can say "le portable" instead of "le téléphone portable."