Appendixs, Additional Recommended Resources, Full Citations and Permissions

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 109895

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Appendix A

Concepts and Strategies for Revision

Let's start with a few definitions. What is an essay? It's likely that your teachers have been asking you to write essays for years now; you've probably formed some idea of the genre. But when I ask my students to define this kind of writing, their answers vary widely and only get at part of the meaning of "essay."

Although we typically talk of an essay (noun), I find it instructive to think about essay (verb): to try; to test; to explore; to attempt to understand. An essay (noun), then, is an attempt and an exploration. Popularized shortly before the Enlightenment Era by Michel de Montaigne, the essay form was invested in the notion that writing invites discovery: the idea was that he, as a lay-person without formal education in a specific discipline, would learn more about a subject through the act of writing itself.

"Effort" by JM Fumeau is licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0

What difference does this new definition make for us, as writers?

- Writing invites discovery. Throughout the act of writing, you will learn more about your topic. Even though some people think of writing as a way to capture a fully-formed idea, writing can also be a way to process through ideas: in other words, writing can be an act of thinking. It forces you to look closer and see more. Your revisions should reflect the knowledge you gain through the act of writing.

- An essay is an attempt, but not all attempts are successful on the first try. You should give yourself license to fail, to an extent. If to essay is to try, then it's okay to fall short. Writing is also an iterative process, which means your first draft isn't the final product.

Now, what is revision? You may have been taught that revision means fixing commas, using a thesaurus to brighten up word choice, and maybe tweaking a sentence or two. However, I prefer to think of revision as "re l vision."

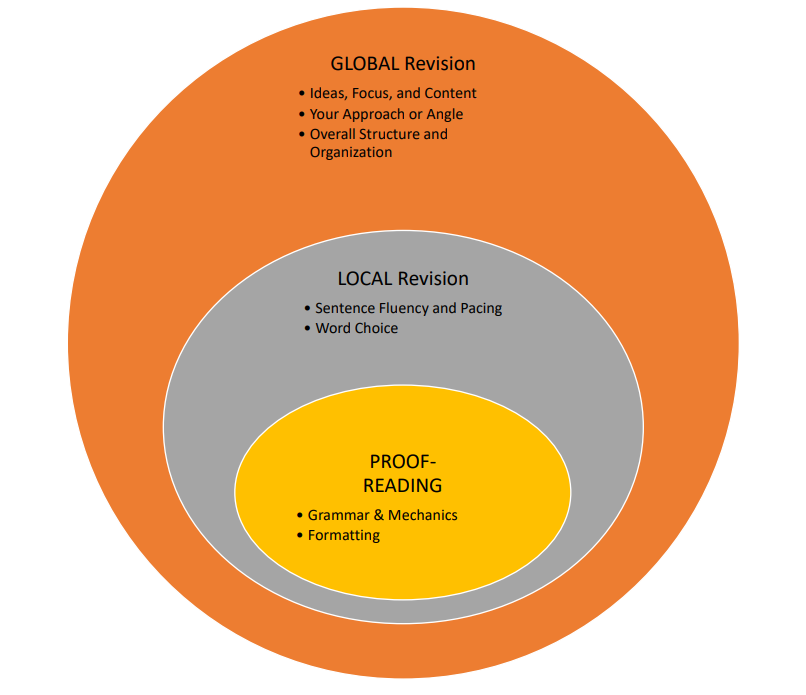

Revision isn't just about polishing—it's about seeing your piece from a new angle, with "fresh eyes." Often, we get so close to our own writing that we need to be able to see it from a different perspective in order to improve it. Revision happens on many levels. What you may have been trained to think of as revision—grammetical and mechanical fixes—is just one tier. Here's how I like to imagine it:

Even though all kinds of revision are valuable, your global issues are first-order concerns, and proofreading is a last-order concern. If your entire topic, approach, or structure needs revision, it doesn't matter if you have a comma splice or two. It's likely that you'll end up rewriting that sentence anyway.

There are a handful of techniques you can experiment with in order to practice true revision. First, if you can, take some time away from your writing. When you return, you will have a clearer head. You will even, in some ways, be a different person when you come back—since we as humans are constantly changing from moment to moment, day to day, you will have a different perspective with some time away. This might be one way for you to make procrastination work in your favor: if you know you struggle with procrastination, try to bust out a quick first draft the day an essay is assigned. Then, you can come back to it a few hours or a few days later with fresh eyes and a clearer idea of your goals.

Second, you can challenge yourself to reimagine your writing using global and local revision techniques, like those included later in this appendix.

Third, you can (and should) read your paper aloud, if only to yourself. This technique distances you from your writing; by forcing yourself you read aloud, you may catch sticky spots, mechanical errors, abrupt transitions, and other mistakes you would miss if you were immersed in your writing. (Recently, a student shared with me that she uses an online text-to-speech voice reader to create this same separation. By listening along and taking notes, she can identify opportunities for local- and proofreading-level revision.)

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, you should rely on your learning community. Because you most likely work on tight deadlines and don’t always have the opportunity to take time away from our projects, you should solicit feedback from your classmates, the Writing Center, your instructor, your Peer Workshop group, or your friends and family. As readers, they have valuable insight to the rhetorical efficacy of your writing: their feedback can be useful in developing a piece which is conscious of audience. To begin setting expectations and procedures for your Peer Workshop, turn to the first activity in this section.

Photo by Mimi Thian on Unsplash

Throughout this text, I have emphasized that good writing cannot exist in a vacuum; similarly, good rewriting often requires a supportive learning community. Even if you have had negative experiences with peer workshops before, I encourage you to give them another chance. Not only do professional writers consistently work with other writers, but my students are nearly always surprised by just how helpful it is to work alongside their classmates.

The previous diagram (of global, local, and proofreading levels of revision) reminds us that everyone has something valuable to offer in a learning community: because there are so many different elements on which to articulate feedback, you can provide meaningful feedback to your workshop, even if you don’t feel like an expert writer.

During the many iterations of revising, remember to be flexible and to listen. Seeing your writing with fresh eyes requires you to step outside of yourself, figuratively. Listen actively and seek to truly understand feedback by asking clarifying questions and asking for examples. The reactions of your audience are a part of writing that you cannot overlook, so revision ought to be driven by the responses of your colleagues.

On the other hand, remember that the ultimate choice to use or disregard feedback is at the author’s discretion: provide all the suggestions you want as a group member, but use your best judgment as an author. If members of your group disagree—great! Contradictory feedback reminds us that writing is a dynamic, transactional action which is dependent on the specific rhetorical audience.

Chapter Vocabulary

| Vocabulary | Definition |

| Essay | a medium, typically nonfiction, by which an author can achieve a variety of purposes. Popularized by Michel de Montaigne as a method of discovery of knowledge: in the original French, “essay” is a verb that means “to try; to test; to explore; to attempt to understand.” |

| Fluff | uneconomical writing: filler language or unnecessarily wordy phrasing. Although fluff occurs in a variety of ways, it can be generally defined as words, phrases, sentences, or paragraphs that do not work hard to help you achieve your rhetorical purpose. |

| Iterative | literally, a repetition within a process. The writing process is iterative because it is non-linear and because an author often has to repeat, revisit, or reapproach different steps along the way. |

| learning community | a network of learners and teachers, each equipped and empowered to provide support through horizontal power relations. Values diversity insofar as it encourages growth and perspective, but also inclusivity. Also, a community that learns by adapting to its unique needs and advantages. |

| Revision |

the iterative process of changing a piece of writing. Literally, re-vision: seeing your writing with “fresh eyes” in order to improve it. Includes changes on Global, Local, and Proofreading levels. Changes might include:

|

Revision Activities

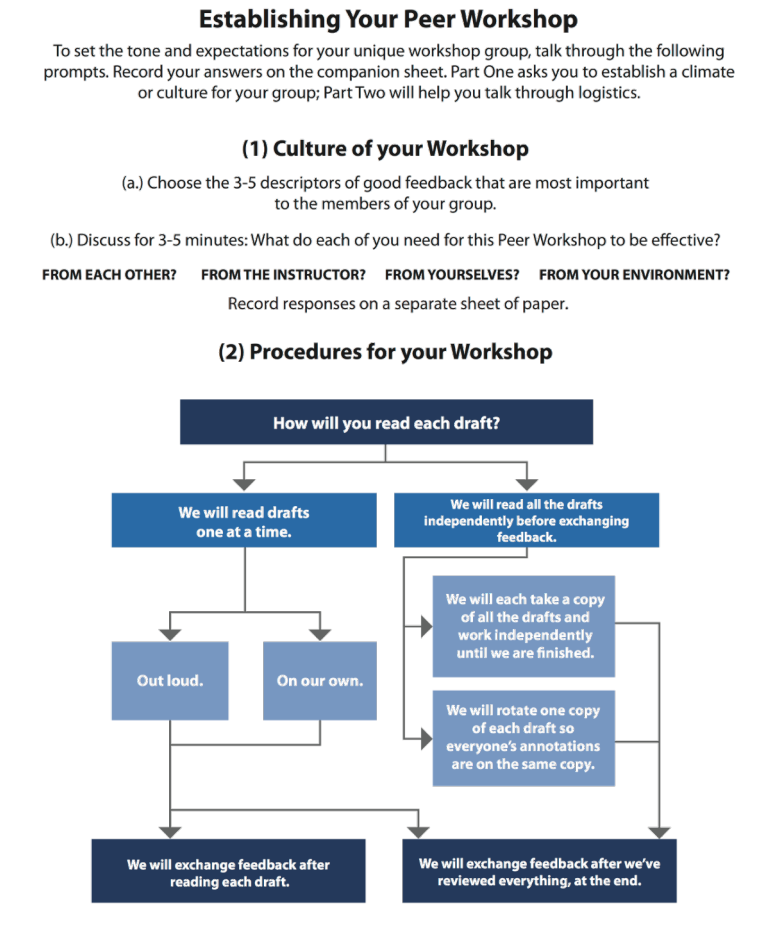

Establishing Your Peer Workshop

Before you begin working with a group, it’s important for you to establish a set of shared goals, expectations, and processes. You might spend a few minutes talking through the following questions:

- Have you ever participated in a Peer Workshop before? What worked? What didn’t?

- What do you hate about group projects? How might you mitigate these issues?

- What opportunities do group projects offer that working independently doesn’t? What are you excited for?

- What requests do you have for your Peer Workshop group members?

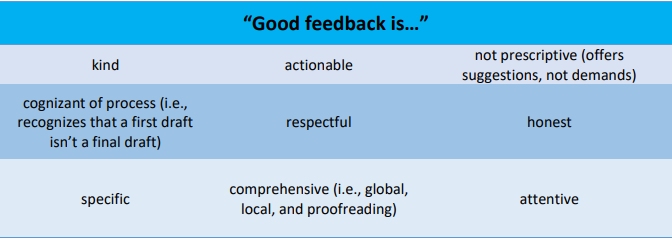

In addition to thinking through the culture you want to create for your workshop group, you should also consider the kind of feedback you want to exchange, practically speaking. In order to arrive at a shared definition for “good feedback,” I often ask my students to complete the following sentence as many times as possible with their groupmates: “Good feedback is…”

The list could go on forever, but here a few that I emphasize:

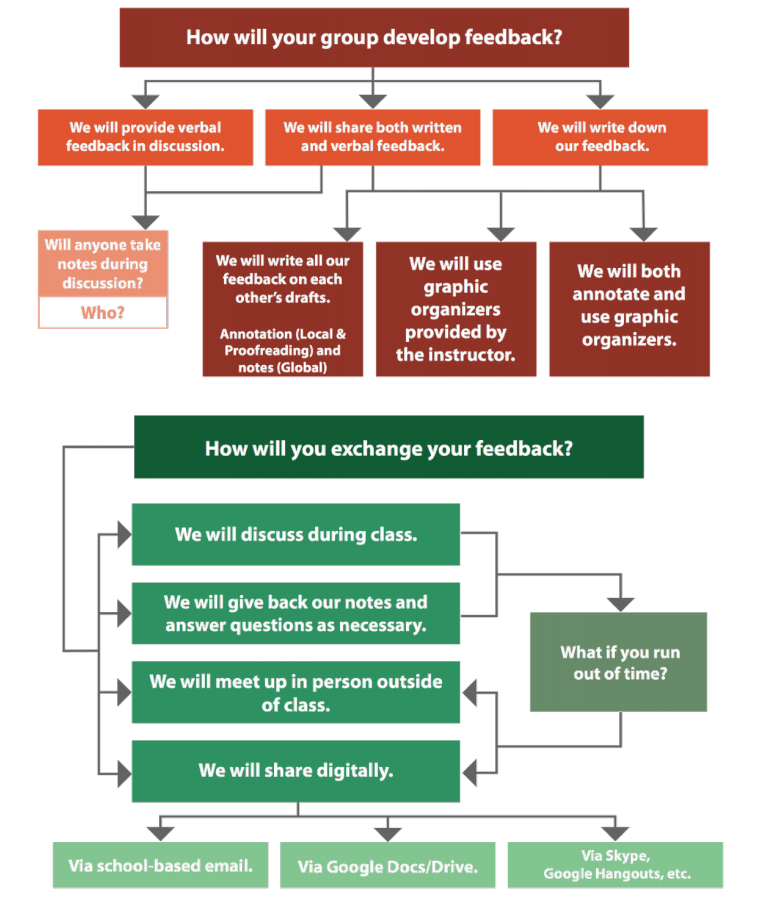

Once you’ve discussed the parameters for the learning community you’re building, you can begin workshopping your drafts, asking, “What does the author do well and what could they do better?” Personally, I prefer a workshop that’s conversational, allowing the author and the audience to discuss the work both generally and specifically; however, your group should use whatever format will be most valuable for you. Before starting your workshop, try to get everyone on the same page logistically by using the flowchart on the following two pages.

Global Revision Activity for a Narrative Essay

This assignment challenges you to try new approaches to a draft you’ve already written. Although you will be “rewriting” in this exercise, you are not abandoning your earlier draft: this exercise is generative, meaning it is designed to help you produce new details, ideas, or surprising bits of language that you might integrate into your project.

First, choose a part of your draft that (a) you really like but think could be better, or (b) just isn’t working for you. This excerpt should be no fewer than 100 words and can include your entire essay, if you want.

Then, complete your choice of one prompt from the list below: apply the instruction to the excerpt to create new content. Read over your original once, but do not refer back to it after you start writing. Your goal here is to deviate from the first version, not reproduce it. The idea here is to produce something new about your topic through constraint; you are reimagining your excerpt on a global scale.

After completing one prompt, go back to the original and try at least one more, or apply a different prompt to your new work.

- Change genres: For example, if your excerpt is written in typical essay form, try writing it as poetry, or dialogue from a play/movie, or a radio advertisement.

- Zoom in: Focus on one image, color, idea, or word from your excerpt and zoom way in. Meditate on this one thing with as much detail as possible.

- Zoom out: Step back from the excerpt and contextualize it with background information, concurrent events, information about relationship or feelings.

- Change point-of-view: Try a new vantage point for your story by changing pronouns and perspective. For instance, if your excerpt is in first-person (I/me), switch to second- (you) or third-person (he/she/they).

- Change setting: Resituate your excerpt in a different place, or time.

- Change your audience: Rewrite the excerpt anticipating the expectations of a different reader than you first intended. For example, if the original excerpt is in the same speaking voice you would use with your friends, write as if your strictest teacher or the president or your grandmother is reading it. If you’ve written in an “academic” voice, try writing for your closest friend—use slang, swear words, casual language, whatever.

- Add another voice: Instead of just the speaker of the essay narrating, add a listener. This listener can agree, disagree, question, heckle, sympathize, apologize, or respond in any other way you can imagine. (See “the nay-sayer’s voice” in Chapter Nine.)

- Change timeline (narrative sequence): Instead of moving chronologically forward, rearrange the events to bounce around.

- Change tense: Narrate from a different vantage point by changing the grammar. For example, instead of writing in past tense, write in present or future tense.

- Change tone: Reimagine your writing in a different emotional register. For instance, if your writing is predominantly nostalgic, try a bitter tone. If you seem regretful, try to write as if you were proud.

Reverse Outlining

Have you ever written an outline before writing a draft? It can be a useful pre-writing strategy, but it doesn’t work for all writers. If you’re like me, you prefer to brain-dump a bunch of ideas on the paper, then come back to organize and refocus during the revision process. One strategy that can help you here is reverse outlining.

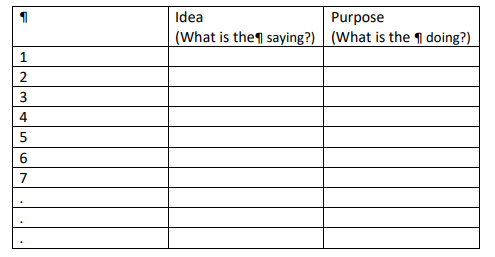

Divide a blank piece of paper into three columns, as demonstrated below. Number each paragraph of your draft, and write an equal numbered list down the left column of your blank piece of paper. Write “Idea” at the top of the middle column and “Purpose” at the top of the right column.

Now, wade back through your essay, identifying what each paragraph is saying and what each paragraph is doing. Choose a few key words or phrases for each column to record on your sheet of paper.

- Try to use consistent language throughout the reverse outline so you can see where your paragraphs are saying or doing similar things

- A paragraph might have too many different ideas or too many different functions for you to concisely identify. This could be a sign that you need to divide that paragraph up.

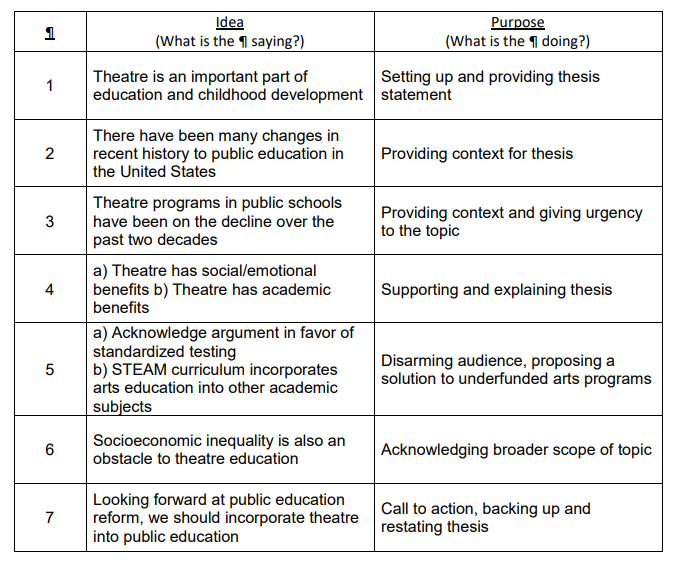

Here's a student's model reverse outline: 136

But wait—there’s more!

Once you have identified the idea(s) and purpose(s) of each paragraph, you can start revising according to your observations. From the completed reverse outline, create a new outline with a different sequence, organization, focus, or balance. You can reorganize by

- combining or dividing paragraphs,

- re-arranging ideas, and

- adding or subtracting content.

Reverse outlining can also be helpful in identifying gaps and redundancies: now that you have a new outline, do any of your ideas seem too brief? Do you need more evidence for a certain argument? Do you see ideas repeated more than necessary?

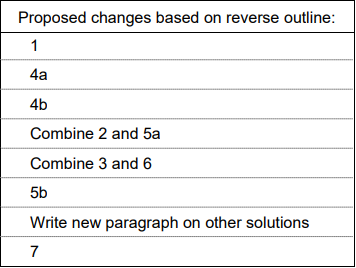

After completing the reverse outline above, the student proposed this new organization:137

You might note that this strategy can also be applied on the sentence and section level. Additionally, if you are a kinesthetic or visual learner, you might cut your paper into smaller pieces that you can physically manipulate.

Be sure to read aloud after reverse outlining to look for abrupt transitions.

You can see a simplified version of this technique demonstrated in this video.

Example of fluff on social media [“Presidents don’t have to be smart” from funnyjunk.com].

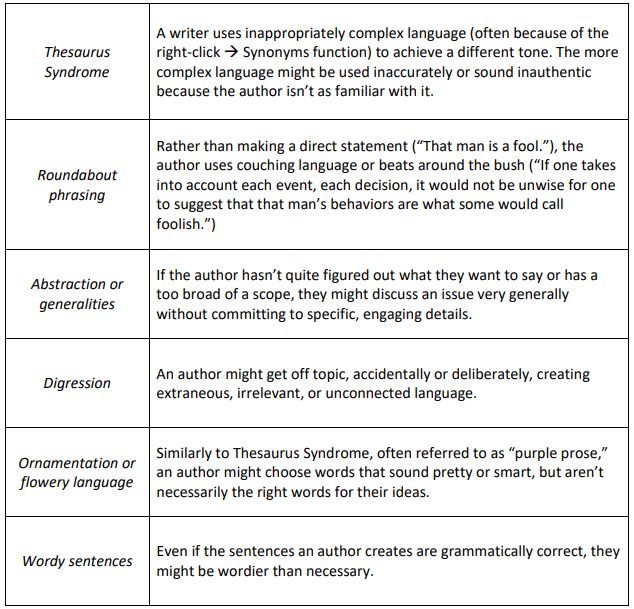

Fluff happens for a lot of reasons.

- Of course, reaching a word- or page-count is the most common motivation.

- Introductions and conclusions are often fluffy because the author can't find a way into or out of the subject, or because the author doesn't know enough about the subject or that their scope is too broad.

- Sometimes, the presence of fluff is an indication that the author doesn't know enough about the subject or that their scope is too broad.

- Other times, fluffy language is deployed in an effort to sound "smarter" or "fancier" or "more academic" — which is an understandable pitfall for developing writers/

These circumstances, plus others, encourage us to use language that's not as effective, authentic, or economical. Fluff happens in a lot of ways; here are a few I've noticed:

Of course, there's a very fine line between detail and fluff. Avoiding fluff doesn't mean always using the fewest words possible. Instead, you should occasionally ask yourself in the revision process, How is this part contributing to the whole? Is this somehow building toward a bigger purpose? If the answer is no, then you need to revise.

The goal should not necessarily be "Don't write fluff," but rather "Learn to get rid of fluff in revision." In light of our focus on process, you are allowed to write fluff in the drafting period, so long as you learn to "prune" during revisions. (I used the word "prune" as an analogy for caring for a plant: just as you must cut the dead leaves off for the plant's health and growth, you will need to cut fluff so your writing can thrive.)

Here are a few strategies:

- Read out loud,

- Ask yourself what a sentence is doing, rhetorically,

- Combine like sentences, phrases, or ideas,

- Use signposts, like topic-transition sentences (for yourself during revision and for your reader in the final draft), and

- Be specific—stay cognizant of your scope (globally) and the detail of your writing (locally).

To practice revising for fluff, workshop the following excerpt by yourself or with a partner. Your goal is not to cut back to the smallest number of words, but rather to prune out what you consider to be fluff and leave what you consider to detail. You should be able to explain the choices you make.

There was a time long before today when an event occurred involving a young woman who was known to the world as Goldilocks. On the particular day at hand, Goldilocks made a spontaneous decision to wander through the forest, the trees growing up high above her flowing blonde pigtails. Some time after she commenced her voyage, but not after too long, she saw sitting on the horizon a small residency. Goldilocks rapped her knuckles on the door, but alas, no one answered the door. Therefore, Goldilocks decided that it would be a good idea to enter the unattended house, so she entered it. Atop the average-sized table in the kitchen of the house, there were three bowls of porridge, which is similar to oatmeal. Porridge is a very common dish in Europe; in fact, the Queen of England is well-known for enjoying at least one daily bowl of porridge per day. Goldilocks, not unlike the Queen of England, enjoys eating porridge for its nutritional value. On this day, she was feeling quite hungry and wanted to eat. She decided that she should taste one of the three bowls of porridge, from which steam was rising indicating its temperature. But, because she apparently couldn’t tell, she imbibed a spoonful of the porridge and vocalized the fact that the porridge was of too high a temperature for her to masticate and consume: “This porridge is too hot!

Appendix A Endnotes

Complete citations are included at the end of the book.

136 Reverse outline by Jacob Alexander, Portland Community College, 2018. Reproduced with permission from the student author.

137 Ibid.

Appendix B

Engaged Reading Strategies

There are a lot of ways to become a better writer, but the best way I know is to read a lot. Why? Not only does attentive reading help you understand grammar and mechanics more intuitively, but it also allows you to develop your personal voice and critical worldviews more deliberately. By encountering a diversity of styles, voices, and perspectives, you are likely to identify the ideas and techniques that resonate with you; while your voice is distinctly yours, it is also a unique synthesis of all the other voices you’ve been exposed to.

But it is important to acknowledge that the way we read matters. At some point in your academic career, you’ve probably encountered the terms “active reading” or “critical reading.” But what exactly does active reading entail?

It begins with an acknowledgement that reading, like writing, is a process: active reading is complex, iterative, and recursive, consisting of a variety of different cognitive actions. Furthermore, we must recognize that the reading process can be approached many different ways, based on our backgrounds, strengths, and purposes.

However, many people don't realize that there's more than one way to read; our early training as readers fosters a very narrow vision of critical literacy. For many generations in many cultures across the world, developing reading ability has generally trended toward efficiency and comprehension of main ideas. Your family, teachers, and other folks who taught you to read trained you to read in particular ways. most often, novice readers are encourage to ignore detail and nuance in the name of focus: details are distracting. Those readers also tend to project their assumptions on a text. This practice, while useful for global understanding of a text, is only one way to approach reading; by itself, it does not constitute "engaged reading." In her landmark article on close reading, Jane Gallop explains that ignoring details while reading is effective, but also problematic:

When the reader concentrates on the familiar, she is reassured that what she already knows is sufficient in relation to this new book. Focusing on the surprising, on the other hand, would mean giving up the comfort of the familiar, of the already known for the sake of learning, of encountering something new, something she didn’t already know. In fact, this all has to do with learning. Learning is very difficult; it takes a lot of effort. It is of course much easier if once we learn something we can apply what we have learned again and again. It is much more difficult if every time we confront something new, we have to learn something new. Reading what one expects to find means finding what one already knows. Learning, on the other hand, means coming to know something one did not know before. Projecting is the opposite of learning. As long as we project onto a text, we cannot learn from it, we can only find what we already know. Close reading is thus a technique to make us learn, to make us see what we don’t already know, rather than transforming the new into the old.138

To be engaged readers, we must avoid projecting our preconceived notions onto a text. To achieve deep, complex understanding, we must consciously attend to a text using a variety of strategies.

The following strategies are implemented by all kinds of critical readers; some readers even use a combination of these strategies. Like the writing process, though, active reading looks different for everyone. These strategies work really well for some people, but not for others: I encourage you to experiment with them, as well as others not covered here, to figure out what your ideal critical reading process looks like.

Chapter Vocabulary

| Vocabulary | Defintion |

| annotation |

engaged reading strategy by which a reader marks up a text with their notes, questions, new vocabulary, ideas, and emphasis |

| critical/active reading | also referred to in this text as engaged reading, a set of strategies and concepts to interrupt projection and focus on a text. |

| SQ3R | an engaged reading strategy to improve comprehension and interrupt projection. Survey, Question, Read, Recite, Review. |

Annotation

Annotation is the most common and one of the most useful engaged reading strategies. You might know it better as “marking up” a text. Annotating a reading is visual evidence to your teacher that you read something—but more importantly, it allows you to focus on the text itself by asking questions and making notes to yourself to spark your memory later.

Take a look at the sample annotation on the next page. Note that the reader here is doing several different things:

- Underlining important words, phrases, and sentences. Many studies have shown that underlining or highlighting alone does not improve comprehension or recall; however, limited underlining can draw your eye back to curious phrases as you re-read, discuss, or analyze a text.

- Writing marginal notes. Even though you can’t fit complex ideas in the margins, you can:

- use keywords to spark your memory,

- track your reactions,

- remind yourself where an important argument is,

- define unfamiliar words,

- draw illustrations to think through an image or idea visually, or

- make connections to other texts.

In addition to taking notes directly on the text itself, you might also write a brief summary with any white space left on the page. As we learned in Chapter Two, summarizing will help you process information, ensure that you understand what you’ve read, and make choices about which elements of the text to focus on.

For a more guided process for annotating an argument, follow these steps from Brian Gazaille,139 a teacher at University of Oregon:

Most “kits” that you find in novelty stores give you materials and instructions about how to construct an object: a model plane, a bicycle, a dollhouse. This kit asks you to deconstruct one of our readings, identifying its thesis, breaking down its argument, and calling attention to the ways it supports its ideas. Dissecting a text is no easy task, and this assignment is designed to help you understand the logic and rhetoric behind what you just read.

Print out a clean copy of the text and annotate it as follows:

- With a black pen, underline the writer’s thesis. If you think the thesis occurs over several sentences, underline all of them. If you think the text has an implicit (present but unstated) thesis, underline the section that comes closest to being the thesis and rewrite it as a thesis in the margins of the paper.

- With a different color pen, underline the “steps” of the argument. In the margins of the paper, paraphrase those steps and say whether or not you agree with them. To figure out the steps of the argument, ask: What was the author’s thesis? What ideas did they need to talk about to support that thesis? Where and how does each paragraph discuss those ideas? Do you agree with those ideas?

- With a different color pen, put [brackets] around any key terms or difficult concepts that the author uses, and define those terms in the margins of the paper.

- With a different color pen, describe the writer’s persona at the top of the first page. What kind of person is “speaking” the essay? What kind of expertise do they have? What kind of vocabulary do they use? How do they treat their intended audiences, or what do they assume about you, the reader?

- Using a highlighter, identify any rhetorical appeals (logos, pathos, ethos). In the margins, explain how the passage works as an appeal. Ask: What is the passage asking you to buy into? How does it prompt me to reason (logos), feel (pathos), or believe (ethos)?

- At the end of the text, and in any color pen, write any questions or comments or questions you have for the author. What strikes you as interesting/odd/infuriating/ insightful about the argument? Why? What do you think the author has yet to discuss, either unconsciously or purposely?

For a more guided process for annotating a short story or memoir, follow these steps from Brian Gazaille,140 a teacher at University of Oregon:

Most “kits” that you find in novelty stores give you materials and instructions about how to construct an object: a model plane, a bicycle, a dollhouse. This kit asks you to deconstruct one of our readings, identifying its thesis, breaking down its argument, and calling attention to the ways it supports its ideas. Dissecting a text is no easy task, and this assignment is designed to help you understand the logic and rhetoric behind what you just read.

Print out a clean copy of the text and annotate it as follows:

- In one color, chart the story’s plot. Identify these elements in the margins of the text by writing the appropriate term next to the corresponding part[s] of the story. (Alternatively, draw a chart on a separate piece of paper.) Your plot chart must include the following terms: exposition, rising action, crisis, climax, falling action, dénouement.

- At the top of the first page, identify the story’s point of view as fully as possible. (Who is telling the story? What kind of narration is given?) In the margins, identify any sections of text in which the narrator’s position/intrusion becomes significant.

- Identify your story’s protagonist and highlight sections of text that supply character description or motivation, labeling them in the margins. In a different color, do the same for the antagonist(s) of the story.

- Highlight (in a different color) sections of the text that describe the story’s setting. Remember, this can include place, time, weather, and atmosphere. Briefly discuss the significance of the setting, where appropriate.

- With a different color, identify key uses of figurative language—metaphors, similes, and personifications—by [bracketing] that section of text and writing the appropriate term.

- In the margins, identify two distinctive lexicons (“word themes” or kinds of vocabulary) at work in your story. Highlight (with new colors) instances of those lexicons.

- Annotate the story with any comments or questions you have. What strikes you as interesting? Odd? Why? What makes you want to talk back? Does any part of the text remind you of something else you’ve read or seen? Why?

SQ3R

This is far and away the most underrated engaged reading strategy I know: the few students I’ve had who know about it swear by it.

The SQ3R (or SQRRR) strategy has five steps:

Before Reading:

Survey (or Skim): Get a general idea of the text to prime your brain for new information. Look over the entire text, keeping an eye out for bolded terms, section headings, the “key” thesis or argument, and other elements that jump out at you. An efficient and effective way to skim is by looking at the first and last sentences of each paragraph.

While Reading:

Question: After a quick overview, bring yourself into curiosity mode by developing a few questions about the text. Developing questions is a good way to keep yourself engaged, and it will guide your reading as you proceed.

- What do you anticipate about the ideas contained in the text?

- What sort of biases or preoccupations do you think the text will reflect?

Read: Next, you should read the text closely and thoroughly, using other engaged reading strategies you've learned.

- Annotate the text: underline/highlight important passages and makes notes to yourself in the margins.

- Record vocabulary words you don't recognize.

- Pause every few paragraphs to check in with yourself and make sure you're confident about what you just read.

- Take notes on a separate page as you see fit.

Recite: As you're reading, take small breaks to talk to yourself aloud about the ideas and information you're processing. I know this seems childish, but self-talk is actually really important and really effective. (It's only as adolescents that we develop this aversion to talking to ourselves because it's frowned upon socially.) If you feel uncomfortable talking to yourself, try to find a willing second party—a friend, roommate, classmate, significant other, family member, etc.—who will listen. If you have a classmate with the same reading assignment, practice this strategy collaboratively!

After Reading:

Review: When you're finished reading, spend a few minutes "wading" back through the text: not diving back in and re-reading, but getting ankle-deep to refresh yourself. Reflect on the ideas the text considered, information that surprised you, the questions that remain unanswered or new questions you have, and the text's potential use-value. The Cornell note-taking system recommends that you write a brief summary, but you can also free-write or talk through the main points that you remember. If you're working with a classmate, try verbally summarizing.

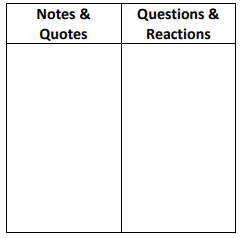

Double-Column Notes

This note-taking strategy seems very simple at first pass, but will help you organized as you interact with a reading.

Divide a clean sheet of paper into two columns; on the left, make a heading for "Notes and Quotes," and on the right, "Questions and Reactions." As you read and re-read, jot down important ideas and words from the text on the left, and record your intellectual and emotional reactions on the right. Be sure to ask prodding questions of the text along the way, too!

By utilizing both columns, you are reminding yourself to stay close to the text (left side) while also evaluating how that text acts on you (right side). This method strengthens the connection you build with a reading.

Increasing Reading Efficiency

Although reading speed is not the most important part of reading, we often find ourselves with too much to read and too little time. Especially when you're working on an inquiry-based research project, you'll encounter more texts than you could possibly have time to read thoroughly. Here are a few quick tips:

Encountering an Article in a Hurry:

1. Some articles, especially scholarly articles, have abstracts. An abstract is typically an overview of the discussion, interests, and findings of an article; it's a lot like a summary. Using the abstract, you can get a rough idea of the contents of an article and determine whether it's worth reading more closely.

2. Some articles will have a conclusion set off at the end of the article. Often, these conclusions will summarize the text and its main priorities. You can read the conclusion before reading the rest of the article to see if its final destination is compatible with yours.

3. If you're working on a computer with search-enabled article PDFs, webpages, or documents, use the "Find" function (Crtl + F on a PC and ⌘ + F on a Mac) to locate keywords. It's possible that you know what you're looking for: use technology to get you there faster.

Encountering a Book in a Hurry:

Although print books are more difficult to speed-read, they are very valuable resources for a variety of reading and writing situations. To get a broad idea of a book's contents, try the following steps:

1. Check the Table of Contents and the Index. At the front and back of the book, respectively, these resources provide more key terms, ideas, and topics that may or may not seem relevant to your study.

2. If you've found something of interest in the Table of Contents and/or Index, turn to the chapter/section of interest. Read the first paragraph, the (approximate) middle two to three paragraphs, and the last paragraph. Anything catch your eye? (If not, it may be worth moving on.)

3. If the book has an introduction, read it: many books will develop their focus and conceptual frameworks in this section, allowing you to determine whether the text will be valuable for your purposes.

4. Finally, check out "5 Ways to Read Faster That ACTUALLY Work - College Info Geek" [Video] that has both practical tips to increase reading speed and conceptual reminders about the learning opportunities that reading creates.

Appendix B Endnotes

Complete citations are included at the end of the book.

138 Gallop 11.

139 This activity was developed by Brian Gazaille, University of Oregon, 2018. Reproduced with permission of the author.

140 Ibid.

Appendix C: Metacognition

Glaciers are known for their magnificently slow movement. To the naked eye, they appear to be giant sheets of ice; however, when observed over long periods of time, we can tell that they are actually rivers made of ice.141

Despite their pace, though, glaciers are immensely powerful. You couldn’t notice in the span of your own lifetime, but glaciers carve out deep valleys (like the one to the right) and grind the earth down to bedrock.142 Massive changes to the landscape and ecosystem take place over hundreds of thousands of years, making them difficult to observe from a human vantage point.

"Photo" by National Park Service is in the Public Domain

"Photo" by National Park Service is in the Public Domain

Despite their pace, though, glaciers are immensely powerful. You couldn’t notice in the span of your own lifetime, but glaciers carve out deep valleys (like the one to the right) and grind the earth down to bedrock.142 Massive changes to the landscape and ecosystem take place over hundreds of thousands of years, making them difficult to observe from a human vantage point.

However, humans too are always changing, even within our brief lifetimes. No matter how stable our sense of self, we are constantly in a state of flux, perpetually changing as a result of our experiences and our context. Like with glaciers, we can observe change with the benefit of time; on the other hand, we might not perceive the specific ways in which we grow on a daily basis. When change is gradual, it is easy to overlook.

Particularly after challenging learning experiences, like those embraced by this textbook, it is crucial that you reflect on the impact those challenges had on your knowledge or skillsets, your worldviews, and your relationships.

Throughout your studies, I encourage you to occasionally pause to evaluate your progress, set new goals, and cement your recent learning. If nothing else, take 10 minutes once a month to free-write about where you were, where you are, and where you hope to be.

You may recognize some of these ideas from Chapter 3: indeed, what I’m talking about is the rhetorical gesture of reflection. Reflection is “looking back in order to look forward,” a way of peering back through time to draw insight from an experience that will support you (and your audience) as you move into the future.

I would like to apply this concept in a different context, though: instead of reflecting on an experience that you have narrated, as you may have in Section 1, you will reflect on the progress you’ve made as a critical consumer and producer of rhetoric through a metacognitive reflection.

Diagram is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 / A derivative from the original work

Simply put, metacognition means “thinking about thinking.” For our purposes, though, metacognition means thinking about how thinking evolves. Reflection on your growth as a writer requires you to evaluate how your cognitive and rhetorical approaches have changed.

In this context, your metacognitive reflection can evaluate two distinct components of your learning: •

- Concepts that have impacted you: New ideas or approaches to rhetoric or writing that have impacted the way you write, read, think, or understanding of the world.

a) Ex: Radical Noticing, Inquiry-Based Research

- Skills that have impacted you: Specific actions or techniques you can apply to your writing, reading, thinking, or understanding of the world.

a) Ex: Reverse Outlining, Imagery Inventory

Of course, because we are “looking back in order to look forward,” the concepts and skills that you identify should support a discussion of how those concepts and skills will impact your future with rhetoric, writing, the writing process, or thinking processes. Your progress to this point is important, but it should enable even more progress in the future.

Chapter Vocabulary

| Vocabulary | Definition |

| metacognition | literally, "thinking about thinking." May also include how thinking evolves and reflection on growth. |

Metacognitive Activities

There are a variety of ways to practice metacognition. The following activities will help you generate ideas for a metacognitive reflection. Additionally, though, a highly productive means of evaluating growth is to look back through work from earlier in your learning experience. Drafts, assignments, and notes documented your skills and understanding at a certain point in time, preserving an earlier version of you to contrast with your current position and abilities, like artifacts in a museum. In addition to the following activities, you should compare your current knowledge and skills to your previous efforts.

Writing Home from Camp

For this activity, you should write a letter to someone who is not affiliated with your learning community: a friend or family member who has nothing to do with your class or study of writing. Because they haven't been in this course with you, imagine they don't know anything about what we've studied.

Your purpose in the letter is to summarize your learning for an audience unfamiliar with the guiding concepts or skills encountered in your writing class. Try to boil down your class procedures, your own accomplishments, important ideas, memorable experiences, and so on.

Metacognitive Interview

With one or two partners, you will conduct an interview to generate ideas for your metacognitive reflection. You can also complete this activity independently, but there are a number of advantages to working collaboratively: your partner(s) may have ideas that you hadn't thought of ; you may find it easier to think out loud than on paper; and you will realize that many of your challenges have been shared.

During this exercise, one person should interview another, writing down answers while the interviewee speaks aloud. Although the interviewer can ask clarifying questions, the interviewee should talk most. For each question, the interviewee should speak for 1-2 minutes. Then, for after 1-2 minutes, switch roles and respond to the same question. Alternate the role of interviewer and interviewee for each question such that every member gets 1-2 minutes to respond while the other member(s) takes notes.

"Interview job icon job interview conversation" by Tumisu is available under the Pixabay license

After completing all of the questions, independently free-write for five minutes. You can make note of recurring themes, identify surprising ideas, and fill in responses that you didn’t think of at the time.

- What accomplishments are you proud of from this term—in this class, another class, or your non-academic life?

- What activities, assignments, or experiences from this course have been most memorable for you? Most important?

- What has surprised you this term—in a good way or a bad way?

- Which people in your learning community have been most helpful, supportive, or respectful?

- Has your perspective on writing, research, revision, (self-)education, or critical thinking changed this term? How so?

- What advice would you give to the beginning-of-the-term version of yourself?

Model Texts by Student Authors

Model Metacognitive Reflection 1143

I somehow ended up putting off taking this class until the very end of my college career. Thus, coming into it I figured that it would be a breeze because I’d already spent the past four years writing and refining my skills. What I quickly realized is that these skills have become extremely narrow; specifically focused in psychological research papers. Going through this class has truly equipped me with the skills to be a better, more organized, and more diverse writer.

I feel that the idea generation and revision exercises that we did were most beneficial to my growth as a writer. Generally, when I have a paper that I have to write, I anxiously attempt to come up with things that I could write about in my head. I also organize said ideas into papers in my head; rarely conceptualizing them on paper. Instead I just come up with an idea in my head, think about how I’m going to write it, then I sit down and dive straight into the writing. Taking the time to really generate various ideas and free write about them not only made me realize how much I have to write about, but also helped me to choose the best topic for the paper that I had to write. I’m sure that there have been many times in the past when I have simply written a paper on the first idea that came to my mind when I likely could have written a better paper on something else if I really took the time to flesh different ideas out.

Sharing my thoughts, ideas, and writings with my peers and with you have been a truly rewarding experience. I realized through this process that I frequently assume my ideas aren’t my comfort zone in this class and forced myself to present the ideas that I really wanted to talk about, even though I felt they weren’t all that interesting. What I came to experience is that people were really interested in what I had to say and the topics in which I chose to speak about were both important and interesting. This class has made me realize how truly vulnerable the writing process is.

This class has equipped me with the skills to listen to my head and my heart when it comes to what I want to write about, but to also take time to generate multiple ideas. Further, I have realized the important of both personal and peer revision in the writing process. I’ve learned the importance of stepping away from a paper that you’ve been staring at for hours and that people generally admire vulnerability in writing.

Model Metacognitive Reflection 2144

I entered class this term having written virtually nothing but short correspondence or technical documents for years. While I may have a decent grasp of grammar, reading anything I wrote was a slog. This class has helped me identify specific problems to improve my own writing and redefine writing as a worthwhile process and study tool rather than just a product. It has also helped me see ulterior motives of a piece of writing to better judge a source or see intended manipulation.

This focus on communication and revision over perfection was an awakening for me. As I’ve been writing structured documents for years, I’ve been focusing on structure and grammatical correctness over creating interesting content or brainstorming and exploring new ideas. Our class discussions and the article “Shitty First Drafts” have taught me that writing is a process, not a product. The act of putting pen to paper and letting ideas flow out has value in itself, and while those ideas can be organized later for a product they should first be allowed to wander and be played with.

Another technique I first encountered in this class was that of the annotated bibliography. Initially this seemed only like extra work that may prove useful to a reader or a grader. After diving further into my own research however, it was an invaluable reference to organize my sources and guide the research itself. Not only did it provide a paraphrased library of my research, it also shined light on patterns in my sources that I would not have noticed otherwise. I’ve already started keeping my own paraphrased notes along with sources in other classes, and storing my sources together to maintain a personal library.

People also say my writing is dry, but I could never pin down the problem they were driving at. This class was my first exposure to the terms logos, ethos, and pathos, and being able to name and identify different styles of argumentation helped me realize that I almost exclusively use logos in my own writing. Awareness of these styles let me contrast my own writing with how extensively used paths and ethos are in most nonfiction writing found in books and news articles. I’ve noticed how providing example stories or posing questions can keep readers engaged while meaningfully introducing sources in the text, rather than as a parenthetical aside, improves the flow of writing and helps statements land with more authority.

As for narrative writing, I found the Global Revision Exercise for the first essay particularly interesting. To take a piece of writing and intentionally force a different voice or perspective on it showed how I can take improve a boring part of my paper by using a unique voice or style. This could be useful for expanding on reflective sections to evoke a particular feeling in the reader, or in conjunction with the Image Building Exercise to pull the reader into a specific moment.

This class was a requirement for me from which I didn’t expect to gain much. English classes I have taken in the past focused on formulaic writing and grammar or vague literary analysis, and I expected more of the same. Ultimately, I was pleasantly surprised by the techniques covered which are immediately applicable in other classes and more concrete analysis of rhetoric which made the vague ideas touched on before reach a more tangible clarity.

Appendix C Endnotes

Complete citations are included at the end of the book.

141 “Glaciers of Glacier Bay National Park.” National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, 12 March 2018, https://www.nps.gov/glba/learn/kidsyouth/glaciers-of-glacierbay-national-park.htm.

142 Ibid.

143 Essay by an anonymous student author, 2017. Reproduced with permission from the student author.

144 Essay by Benjamin Duncan, Portland State University, 2017. Reproduced with permission from the student author.

Additional Recommended Resources

- “Students' Right to Their Own Language” from NCTE’s Conference on College Composition and Communication

- “Revising Drafts” by the Writing Center at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

- “‘I need you to say “I”’: Why First Person Is Important in College Writing” by Kate McKinney Maddalena [essay]

- “Annoying Ways People Use Sources” by Kyle D. Stedman [essay]

- Your Logical Fallacy Is…

- “Shitty First Drafts” by Anne Lamott from Bird by Bird: Some Instructions on Writing and Life, Anchor, pp 21-27.

- “Argument as Emergence, Rhetoric as Love” by Jim W. Corder [JSTOR access]

- “The Ethics of Reading: Close Encounters” by Jane Gallop from Journal of Curriculum Theorizing, volume 16, issue 3, 2000, pp. 7-17.

- Purdue Online Writing Lab (OWL)

- Purdue OWL Home

- Purdue OWL MLA Style & Citation

- Purdue OWL APA Style & Citation

- Purdue OWL Chicago/Turabian Style & Citation

- A Pocket Style Manual (7th edition, 2016), edited by Diana Hacker and Nancy Sommers [WorldCat]

- A Pocket Style Manual (7th edition, 2016), edited by Diana Hacker and Nancy Sommers [Amazon]

- North Carolina State University Citation Builder

- Citation Management Software - Overview Video

Screenshot from Citation Management Software - Overview Video

Full Citations and Permissions

Images (in order of apperance)

All graphics not cited below were created by the author and are licensed in accordance with the Creative Commons under which the rest of the text is licensed.

Emmett Rose, Portland State University, 2017.

O’Connor, Rebecca. Stories. 2010. Flickr, https://flic.kr/p/7V4zvx. Reproduced with attribution under Creative Commons license.

Sudarman, Henry. Busy Market. 2014. Flickr, https://flic.kr/p/nwBL6U. Reproduced with attribution under Creative Commons license.

Watkins, James. Kansas Summer Wheat and Storm Panorama. 2010. Flickr, https://flic.kr/p/bQKpKV. Reproduced with attribution under Creative Commons license.

Breen, Annina. Taxonomic Rank Graph. 2015. Wikimedia Commons, https://en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Taxonomic_Rank_Graph.svg. Reproduced with attribution under Creative Commons license.

Von Canon, Carol. Stones. 2011. Flickr, https://flic.kr/p/anSmXb. Reproduced with attribution under Creative Commons license.

rossyyume. Story. 2012. Flickr, https://flic.kr/p/cQRAYC. Reproduced with attribution under Creative Commons license.

SBT4NOW. SF neighborhood. 2015. Flickr, https://flic.kr/p/BKFHXk. Reproduced with attribution under Creative Commons license.

Carlos ZGZ. Different Perspective. 2013. Flickr, https://flic.kr/p/ExnsK6. Reproduced from the Public domain.

Wewerka, Ray. Conversation. 2013. Flickr, https://flic.kr/p/jQpg8F. Reproduced with attribution under Creative Commons license.

Fefé, Paolo. Body Language, 2010. Flickr, https://flic.kr/p/7T3quL. Reproduced with attribution under Creative Commons license.

Nilsson, Susanne. Looking back. 2015. Flickr, https://flic.kr/p/qVYEYS. Reproduced with attribution under Creative Commons license.

Goetsch, Steven. CSAF releases 2009 reading list. Air Combat Command, U.S. Air Force, http://www.acc.af.mil/News/Photos/igphoto/2000638216/. Reproduced from the Public domain as a government document.

:jovian:. bf8done. 2012. Flickr, https://flic.kr/p/dAL333. Reproduced with attribution under Creative Commons license.

Silverdrake, Joakim. 090106 Pile of joy. 2009. Flickr, https://flic.kr/p/5QyrcG. Reproduced with attribution under Creative Commons license.

Gumbel, Tony. Obama iPhone Wallpaper, 2008. Flickr, https://flic.kr/p/4rPeax. Reproduced with attribution under Creative Commons license (CC BY-NC 2.0).

Everett, Chris. Pattern (broken). 2012. Flickr, https://flic.kr/p/bVbm1u. Reproduced with attribution under Creative Commons license.

Blogtrepreneur. Social Media Mix 3D Icons - Mix #2. 2016. Flickr, https://flic.kr/p/JWUkuu. Reproduced with attribution under Creative Commons license.

Aainsqatsi, K. Bloom’s Rose. 2008. Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Blooms_rose.svg. Reproduced with attribution under Creative Commons license.

Brick Head. DSC_0119. 2014. Flickr, https://flic.kr/p/piazUu. Reproduced with attribution under Creative Commons license.

Heather. Vintage ephemera. 2008. Flickr, https://flic.kr/p/5JExWt. Reproduced with attribution under Creative Commons license.

Strayer, Reuben. The Biology of Human Sex Differences, 2006. Flickr, https://flic.kr/p/c12Ad. Reproduced with attribution under Creative Commons license.

TukTukDesign. No title. Pixabay, https://pixabay.com/en/icon-leader-leadership-lead-boss1623888/. Reproduced with attribution under Creative Commons license.

GovernmentZA. President Jacob Zuma attends Indigenous and Traditional Leaders Indaba, 2017. Flickr, https://flic.kr/p/U353xT. Reproduced with attribution under Creative Commons license.Pennucci, Jim. Conversation, 2013. Flickr, https://flic.kr/p/k1VCxV. Reproduced with attribution under Creative Commons license.

Vladuchick, Paul. Investigation. 2010. Flickr, https://flic.kr/p/8rQaXM. Reproduced with attribution under Creative Commons license.

ubarchives. Discussion. 2014. Flickr, https://flic.kr/p/nAaehf. Reproduced with attribution under Creative Commons license.

Langager, Andy. Card catalog. 2013. Flickr, https://flic.kr/p/fgTyd1. Reproduced with attribution under Creative Commons license.

Cortes, Daniel. Another Ethernet Switch in the Rack. 2009. Flickr, https://flic.kr/p/6LkW2c. Reproduced with attribution under Creative Commons license.

Arnold, Karen. Signpost Blank. PublicDomainPictures.net, https://www.publicdomainpictures.net/pictures/250000/velka/signpost-blank.jpg. Reproduced with attribution under Creative Commons license. Endless Origami, https://endlessorigami.com/. No link or date available. Reproduced with attribution under Creative Commons license.

Fumeau, JM. Effort. 2015. Flickr, https://flic.kr/p/qX2buJ. Reproduced with attribution under Creative Commons license.

коворкинг-пространство Зона действия. Zonaspace-coworking-collaboration, 2012. Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Zonaspace-coworkingcollaboration.jpg. Reproduced with attribution under Creative Commons license.

fluffypain. presidents don’t have to be smart. funnyjunk.com, 27 Sept. 2015, https://funnyjunk.com/Presidents+don+t+have+to+be+smart/funnypictures/5697805#536742_5697361. Reproduced with attribution in accordance with Fair Use guidelines and funnyjunk.com policy.

White, AD. eflon. 2008. Flickr, https://flic.kr/p/5nZKsE. Reproduced with attribution under Creative Commons license.

Margerie Glacier Aerial View. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, https://www.nps.gov/glba/learn/kidsyouth/images/margerie-glacier-aerialview.jpg?maxwidth=650&autorotate=false. Reproduced from the Public domain as a government document.

U-Shaped Valley. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, https://www.nps.gov/glba/learn/kidsyouth/images/U-ShapedValley.jpg?maxwidth=650&autorotate=false. Reproduced from the Public domain as a government document.

Tumisu. Interview, 2015. Pixabay, https://pixabay.com/photo-1018333/. Reproduced with attribution under Creative Commons license.

Texts (in alphabetical order)

All texts not cited below were provided with written consent from anonymous student authors. All student authors have provided written consent for their work to be reproduced in this textbook.

Ballenger, Bruce. The Curious Researcher, 9th edition, Pearson, 2018.

Baotic, Anton, Florian Sicks and Angela S. Stoeger. "Nocturnal 'Humming' Vocalizations: Adding a Piece of the Puzzle of Giraffe Vocal Communication." Biomed Central Research Notes vol. 8, no. 425, 2015. US National Library of Medicine, doi 10.1186/s13104-015-1394-3.

Barthes, Roland. Image, Music, Text, translated by Stephen Hearth, Hill and Wang, 1977.

Beer, Jessica. “The Advertising Black Hole.” WR-222, Fall 2016, Portland State University, Portland, OR.

Bell, Kayti. “You Snooze, You Peruse.” WR-323, Winter 2017, Portland State University, Portland, OR.

“The Big Bang.” Doctor Who, written by Steven Moffat, BBC, 2010.

Bloom, Benjamin S., et al. Taxonomy of Educational Objectives: The Classification of Educational Goals. D. McKay Co., 1969.

Burke, Kenneth. The Philosophy of Literary Form, University of California Press, 1941.

Butler, Joey. “Under the Knife.” WR-121, Fall 2016, Portland Community College, Portland, OR. Calli, Bryant. “Student Veterans and Their Struggle with Higher Education.” WR-121, Fall 2017, Portland Community College, Portland, OR.

Carroll, Jesse. “Catacombs intro revision.” WR-222, Fall 2015, Portland State University, Portland, OR.

Chan, Chris. “Innocence Again.” WR-121, Fall 2014, Portland State University, Portland, OR.

Chopin, Kate. “The Story of an Hour.” 1894. The Kate Chopin International Society, 13 Aug. 2017, https://www.katechopin.org/story-hour/. Reproduced from the Public domain.

Cioffi, Sandy, director. Sweet Crude. Sweet Crude Movie LLC, 2009.

Coble, Ezra. “Vaccines: Controversies and Miracles.” WR-122, Spring 2018, Portland Community College, Portland, OR.

Curtiss, Tim. “Carnivore Consumption Killing Climate.” WR-121, Winter 2017, Portland Community College, Portland, OR. ——. “Untitled.” WR-121, Winter 2017, Portland Community College, Portland, OR.

de Joya, Carlynn. “All Quiet.” WR-323, Winter 2017, Portland State University, Portland, OR.

Deloria, Jr., Vine. “Power and Place Equal Personality.” Indian Education in America by Deloria and Daniel Wildcat, Fulcrum, 2001, pp. 21-28.

“Developing a Thesis.” Purdue OWL, Purdue University, 2014, https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/616/02/. [Original link has expired. See Purdue OWL’s updated version: Developing a Thesis]

Donne, John. “A Valediction: Forbidding Mourning.” 1633. Reproduced from the Public domain.

Douglass, Frederick. My Bondage and My Freedom, Partridge and Oakey, 1855. “A Change Came O’er the Spirit of My Dream.” Lit2Go, University of Southern Florida, 2017, http://etc.usf.edu/lit2go/45/my-bondage-and-my-freedom/1458/chapter-11-a-changecame-oer-the-spirit-of-my-dream/. Reproduced from the Public domain.

Duncan, Benjamin. “Wage Transparency and the Gender Divide.” WR-121, Fall 2017, Portland State University, Portland, OR.

——. “Metacognitive Conclusion.” WR-121, Fall 2017, Portland State University, Portland, OR.

Ehrenreich, Barbara. Nickel and Dimed, Henry Holt & Co., 2001.

Faces. “Ooh La La.” Ooh La La, 1973.

Franklin. “The Devil in Green Canyon.” WR-122, Summer 2017, Portland Community College, Portland, OR. [Franklin has requested that only his first name be used here.]

Filloux, Frederic. “Facebook’s Walled Wonderland Is Inherently Incompatible with News.” Monday Note, Medium, 4 December 2016, https://mondaynote.com/facebooks-walledwonderland-is-inherently-incompatible-with-news-media-b145e2d0078c.

Foster, Thomas C. How to Read Literature Like a Professor, Harper, 2003.

Gallagher, Kelly. Write Like This, Stenhouse, 2011.

Gallop, Jane. “The Ethics of Reading: Close Encounters.” Journal of Curriculum and Theorizing, Vol. 16., No. 3, 2000, pp. 7-17.

Gawande, Atul. “Why Boston’s Hospitals Were Ready.” The New Yorker, 17 April 2013, https://www.newyorker.com/news/news-desk/why-bostons-hospitals-were-ready.

Gaylord, Christopher. “Death at a Price Only Visitors Will Pay.” WR-222, Spring 2017, Portland State University, Portland, OR.

——. “Planting the Seed: Norway’s Strong Investment in Parental Leave.” WR-222, Spring 2017, Portland State University, Portland, OR.

Gazaille, Brian. “The Reading Analysis Kit.” Reproduced with permission from the author.

——. “The Short Story Kit.” Reproduced with permission from the author.

Geertz, Clifford. The Interpretation of Cultures, Basic Books, 1973.

“Glaciers of Glacier Bay National Park.” National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, 12 March 2018, https://www.nps.gov/glba/learn/kidsyouth/glaciers-of-glacier-baynational-park.htm.

Glass, Ira and Miki Meek. “Our Town.” This American Life, NPR, 8 December 2017, https://www.thisamericanlife.org/632/our-town-part-one.

Greenbaum, Leonard. “The Tradition of Complaint.” College English, vol. 31, no. 2, 1969, pp. 174–187. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/374119.

Greenough, Paul. “Pathogens, Pugmarks, and Political ‘Emergency’: The 1970s South Asian Debate on Nature.” Nature in the Global South: Environmental Projects in South and Southeast Asia, Duke University Press, 2003, pp. 201-230.

Alexander, Jacob. “Reverse Outline.” WR-121, Spring 2018, Portland Community College, 2018.

Han, Shaogang. “Jasmine-Not-Jasmine.” A Dictionary of Maqiao, translated by Julia Lovell, Dial Press, 2005, pp. 352+.

Harding, Beth. “Slowing Down.” WR-323, Winter 2017, Portland State University, Portland, OR.

Holt, Derek. “Parental Guidance.” WR-323, Fall 2017, Portland State University, Portland, OR.

Jiminez, Kamiko, Annie Wold, Maximilian West and Christopher Gaylord. “Close Reading Roundtable.” Fall 2017, Portland State University, Portland, OR. Recording and production assistance from Laura Wilson and Kale Brewer.

Kinsley, Michael. “The Intellectual Free Lunch.” 1995. The Seagull Reader: Essays, Norton, 2016, pp. 251-253.

Koening, John. “Sonder.” The Dictionary of Obscure Sorrows, 22 July 2012, http://www.dictionaryofobscuresorrow...6922667/sonder.

Kreinheder, Beth. “Maggie as the Focal Point.” WR-200, Spring 2018, Portland State University, Portland, OR.

——. “The Space Between the Racial Binary.” WR-200, Spring 2018, Portland State University, Portland, OR.

Le Guin, Ursula K. The Left Hand of Darkness, Ace, 1987.

Lewis, Samantha. “Effective Therapy Through Dance and Movement.” WR-222, Fall 2015, Portland State University, Portland, OR.

Lopez, Cristian. “My Favorite Place.” WR-122, Summer 2017, Portland Community College, Portland, OR.

Maguire, John G., with an introduction by Valerie Strauss. “Why So Many College Students are Lousy at Writing – and How Mr. Miyagi Can Help.” Washington Post, 27 April 2012, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/answer-sheet/wp/2017/04/27/why-so-manycollege-students-are-lousy-at-writing-and-how-mr-miyagi-canhelp/?utm_term=.b7241de544e2.

Marisol Meraji, Shereen and Gene Demby. “The Unfinished Battle in the Capital of the Confederacy.” Code Switch, NPR, 22 August 2017, https://one.npr.org/?sharedMediaId=545267751:545427322.

Marina. “Analyzing ‘Richard Cory.’” WR-121, Spring 2018, Portland Community College, Portland, OR. [Marina has requested that only her first name be used here.]

Marsh, Calum. “Moonlight (Original Motion Picture Soundtrack.” Pitchfork, 30 June 2017, https://pitchfork.com/reviews/albums/nicholas-britell-moonlight-original-motionpicture-soundtrack/.

Mays, Kelly J. The Norton Introduction to Literature, Portable 12th edition, Norton, 2017.

McCallister, Josiah. “A Changing Ball-Game.” WR-222, Spring 2017, Portland State University, Portland, OR.

Mills, Ryan. “Drag the River.” Originally published in 1001, issue 2, by IPRC. Reproduced with permission from the author.

Morris, Katherine. “Untitled.” WR-323, Spring 2016, Portland State University, Portland, OR.

Morris, Kathryn. “Pirates & Anarchy [Annotated Bibliography].” WR-222, Spring 2017, Portland State University, Portland, OR.

——. “Pirates & Anarchy [Proposal].” WR-222, Spring 2017, Portland State University, Portland, OR.

——. “Pirates & Anarchy: Social Banditry Toward a Moral Economy.” WR-222, Spring 2017, Portland State University, Portland, OR.

“My Scrubs.” Scrubs, NBC Universal, 2007.

Naranjo, Celso. “What Does It Mean to Be Educated?” WR-323, Spring 2017, Portland State University, Portland, OR.

O’Brien, Tim. “The Vietnam in Me.” The New York Times: Books, 2 Oct. 1994, http://www.nytimes.com/books/98/09/20/specials/obrien-vietnam.html. Reproduced here under Fair Use guidelines.

Page, Ellen and Ian Daniel, hosts. Gaycation. Viceland, VICE, 2016.

Perrault, Charles. “Little Red Riding Hood.” 1697. Making Literature Matter, 4th edition, edited by John Schlib and John Clifford, Bedford, 2009, pp. 1573-1576.

Preble, Mary. “To Suffer or Surrender? An Analysis of Dylan Thomas’s ‘Do Not Go Gentle into That Good Night.’” WR-200, Spring 2018, Portland State University, Portland, OR.

Reaume, Ross. “Home-Room.” WR-121, Fall 2014, Portland State University, Portland, OR.

——. “Normal Person: An Analysis of The Standards of Normativity in A Plague of Tics.” WR-121, Fall 2014, Portland State University, Portland, OR. The essay presented in this text is a synthesis of Mr. Reaume’s essay and another student’s essay; the latter student wishes to remain anonymous.

Richardson, Cassidy. “Untitled.” WR-323, Fall 2017, Portland State University, Portland, OR.

Robinson, Edwin Arlington. “Richard Cory.” 1897. Reproduced from the Public domain.

Roche, Patrick. “21.” March 2014, CUPSI, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO. Video published by Button Poetry, 24 April 2014, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6LnMhy8kDiQ.

Ryle, Gilbert. Collected Essays (1929-1968), vol. 2, Routledge, 2009, 479+.

Sagan, Carl. Cosmos, Ballantine, 2013.

Saifer, David. “‘Between the World And Me’: An Important Book on Race and Racism.” Tucson Weekly, 25 Aug. 2015, https://www.tucsonweekly.com/TheRange/archives/2015/08/25/between-the-worldand-me-an-important-book-on-race-and-racism. Reproduced with permission from the author and publication.

Shklovsky, Viktor. “Art as Technique.” 1925. Literary Theory: An Anthology, 2nd edition, edited by Julie Rivkin and Michael Ryan, Blackwell, 2004, pp. 12-15.

Sterrett, Catherine. “Economics and Obesity.” WR-121, Fall 2017, Portland Community College, Portland, OR. Taylor, Noel. “The Night She Cried.” WR-121, Fall 2014, Portland State University, Portland, OR.

Uwuajaren, Jarune and Jamie Utt. “Why Our Feminism Must Be Intersectional (And 3 Ways to Practice It).” Everyday Feminisim, 11 Jan. 2015, http://everydayfeminism.com/2015/01/why-our-feminism-must-be-intersectional/.

Vazquez, Robyn. “Running Down the Hill.” 2 July 2017, Deep End Theater, Portland, OR.

——. Interview with Shane Abrams. 2 July 2017, Deep End Theater, Portland, OR.

Vo-Nguyen, Jennifer. “We Don’t Care About Child Slaves.” WR-222, Spring 2017, Portland State University, Portland, OR.

Wetzel, John. “The MCAT Writing Assignment.” WikiPremed, Wisebridge Learning Systems LLC, 2013, http://www.wikipremed.com/mcat_essay.php [Link has expired since publication. For more information, see WikiPremed website.] Reproduced in accordance with Creative Commons licensure.

Wiseman, Maia. “Blood & Chocolate Milk.” WR-121, Fall 2014, Portland State University, Portland, OR.

Yoakum, Kiley. “Comatose Dreams.” WR-121, Fall 2016, Portland Community College, Portland, OR.

Zarnick, Hannah. “A Case of Hysterics [Annotated Bibliography].” WR-222, Spring 2017, Portland State University, Portland, OR.

——. “A Case of Hysterics [Proposal].” WR-222, Spring 2017, Portland State University, Portland, OR.

——. “The Hysterical Woman.” WR-222, Spring 2017, Portland State University, Portland, OR.